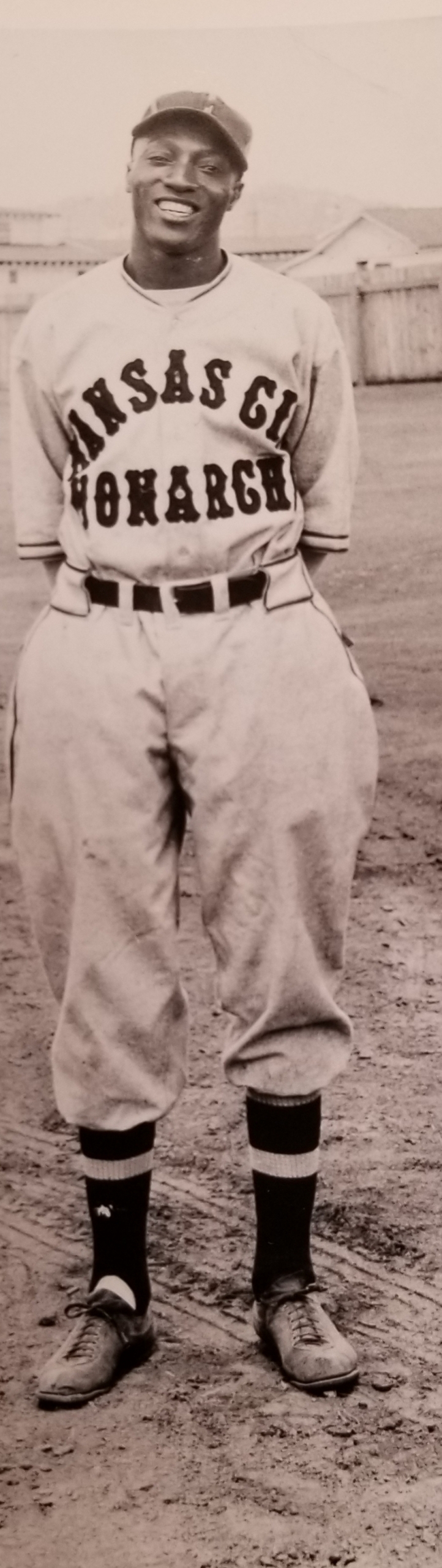

Curtis “Popeye” Harris

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time when black baseball was wide open and strapped for cash, Curtis Harris was in his element. Arriving in Kansas City as a 29-year-old rookie out of Texas in 1931, the good-looking Harris hacked his way from one end of the circuit to the other, leaving opponents, team owners, multiple wives, and at least two children in his wake.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time when black baseball was wide open and strapped for cash, Curtis Harris was in his element. Arriving in Kansas City as a 29-year-old rookie out of Texas in 1931, the good-looking Harris hacked his way from one end of the circuit to the other, leaving opponents, team owners, multiple wives, and at least two children in his wake.

In a career that spanned just over a decade, Harris played and barnstormed with some of the game’s greatest players, including Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and Judy Johnson. Known alternatively as Popeye, Popsicle, or Muchie, Harris was a utility player of the highest order. Cool Papa Bell remembered Harris as a versatile “underrated hitter” with speed to burn, once gathering a pair of inside-the-park homers in one game when both played for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1932.1

Today Harris would be considered a “super utility” player and major-league clubs would wager millions on his services. As it was, however, he scratched a dusty, road-weary, segregated existence, playing baseball wherever the money was, and passing well before his time.

Curtis Harris was born to Willie and Vinia (Vinah) Lewis Taplin on February 14, 1902, near Indian Creek in Burton, Texas, a small agricultural and railroad community in western Washington County.2 Both Willie and Vinia were born in Washington County, as were Vinia’s parents, Steve and Jennie Lewis. Willie Harris, a farm laborer, died sometime before 1910, and Vinia married Sandy Taplin. Her son Stephen assumed the Taplin name while Curtis and Henry remained Harris, though the 1920 census taker struck a line through an “H” for their last name and inserted Taplin instead. Vinia, a widow in 1910, was working as a farm laborer to support her boys. By 1920 she had moved inside as a hotel cook in Washington County. Later documents indicate that Henry continued to go by Harris and so did Curtis. Curtis is shown as living with his mother through at least 1920.3 Vinia died of a cerebral hemorrhage in April 1948 while living in Somerville, Texas.

While there is little information on Curtis Harris’s childhood, or what turned him to baseball, it is known that by 1926 he was playing with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Southern National League – as a pitcher, infielder, and catcher – and that he was a teammate of a fellow Texan, left-handed pitcher Charles Beverly. Beverly had played for the Black Barons the previous year and perhaps persuaded Harris to join him on the 1926 pennant-winning squad. Harris and Beverly ended up having a lengthy partnership as teammates throughout their professional baseball careers.4

There was excitement in Birmingham during the spring of 1926, much of it centering on the Black Barons and their entry into the revived Negro Southern League (NSL). The Birmingham Reporter noted that veteran Clarence Smith would manage the club and play outfield, with R.T. Jackson serving as club secretary. The NSL was an eight-team loop that year with clubs in Birmingham, Montgomery, Nashville, Memphis, Chattanooga, New Orleans, Atlanta, and Albany, Georgia. With the season opener slated for May 1, Smith had the Black Barons on the road throughout April playing exhibitions to round into shape. In mid-April they played three games at the Meridian Giants, taking “Um All” by scores of 17-1, 5-1, and 10-0. Harris caught the second game, Eli Juran pitching, and then moved to shortstop for game three and belting a homer. Beverly was the winner in game three. A week later, the Black Barons took three games from a competitive squad stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. While playing left field, Harris made a “pretty shoestring catch in the seventh,” checking the soldiers’ late rally.5

Harris’s play earned him a spot on the Black Barons when the regular season began, though he saw little action early on. As the Black Barons set a torrid early pace, claiming series wins at Chattanooga, Memphis, Albany, and Nashville, neither Harris nor Beverly made much noise in the weekly box scores. After a sweep of Nashville in early June, however, Harris began to appear, but more often than not as a pitcher. By the second week of June, with Birmingham having won 28 consecutive games, 21 league and 7 exhibitions, and sitting two up in first place, Harris was listed in the Reporter as part of the pitching staff.6

The Black Barons faced Memphis in the SNBL championship series, a 10-game set that drew large crowds in both cities and lasted over three weeks. Birmingham jumped to an early series lead, winning three and tying two, the draws coming because of darkness, before winning 2-0 at Rickwood Field. The series then shifted to Memphis, where after the home team took two games and tied another. Jim Jeffries, acquired before the series from Albany, was dominant and scattered four hits in a “decisive” 9-3 victory to claim the 1926 SNBL pennant. As the Pittsburgh Courier explained, it was the Barons’ effective pitching “in the pinches” that was the deciding factor, “coupled with timely hitting and stellar fielding.” While Harris and Beverly, for that matter, had been vital contributors to the team at certain points in the season, neither proved consequential down the stretch. While there was some talk of the Black Barons possibly playing a “Dixie Series” against Dallas of the Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana League, or maybe the winner of the Negro National Baseball League, it “failed to materialize.”7

Where Curtis Harris was during the 1927 and 1928 campaigns continues to be a matter of speculation. There was a Harris who played shortstop and pitched for the Evansville Reichert Giants and another who pitched for the Atlanta Black Crackers, both member teams of the black Negro Southern League. The Black Crackers disbanded by mid-June that year and perhaps that is why so little information on Harris exists. Charles Beverly, who up to this point had played with or in the same league as Harris, was with the Nashville Elites in 1927 and 1928, so Harris may have played in the South as well, but it is not certain. What is known is that by 1929, both Harris and Beverly were in the Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana League, where they played for the San Antonio Black Indians, a club managed in 1929 by W.P. Patterson, who had been Beverly’s manager in Birmingham in 1925.8

The league itself served as a minor-league circuit of sorts for better-known and well-traveled teams like the Kansas City Monarchs and Homestead Grays, which would occasionally drop in for a weekend series while scouting prospective players.9 Curtis Harris, along with Charles Beverly, reportedly “came to San Antonio from Houston” to play for Patterson and the Black Indians in 1929 and stayed with the club through late June 1931.10 It is possible that Harris played for Patterson in Houston in 1927 and/or 1928, though there are no records found to support it other than the reference that they arrived together in San Antonio from Houston.11

During the 1929 season, Harris was 13-for-45 at the plate, batting .288, while finishing 2-1 on the mound in six appearances.12 Against the Dallas Black Giants near the end of April, he began the game on the mound, but was chased after allowing Dallas to knot the score, 3-3, in the third on eight hits, giving way to Charles Beverly, who allowed only a single run the rest of the way. Going behind the plate to catch Beverly, Harris finished the game with two hits, and a run scored as the Black Indians won, 8-4. Harris’s best offensive outing of the season came two days later when against the same Dallas squad, he was 3-for-5 with a sacrifice and two runs scored in a 15-6 win. Dallas committed 14 errors in the affair and was swept in the three-game set.13 Perhaps Harris’s strongest showing of the season as a pitcher came in late July when he tossed a complete-game 12-inning contest, allowing three runs on 11 scattered hits in getting a 4-3 win over Shreveport.14

Many of the Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana League’s 1929 games, as well as the entire 1930 season, were covered only scantly in the local press. Three articles early in the 1930 season focused more on the lights brought by the Kansas City Monarchs for an exhibition set with the Black Indians than on the games themselves. As a bankrupt nation struggled during the early 1930s, baseball entrepreneurs did whatever they could to draw attendance, and for the Monarchs it was night baseball on a barnstorming circuit. It was also evident that playing night baseball was something the citizens of San Antonio desired, and a good deal of coverage was afforded to these games.15

The Monarchs, “traveling like a circus,” trucked a light plant built on special order by team owner J.L. Wilkinson, “one of the most respected and influential figures in the history of black baseball,” to San Antonio rivaling “anything ever built in the way of electrical equipment.” The “unique plant,” weighing five tons, consisted of a generator connected to a 250-horsepower, six-cylinder gas engine. The 100 kilowatts of power generated was transferred to a series of floodlights installed atop 45- to 50-foot high light poles around the field in such a manner that the entire field was “as light as day.” It was said that the entire system could be made ready within two hours with no holes dug, no bracing attached to the grandstand or other buildings, the system working off tripods. The plant was put on display in downtown San Antonio for two days prior to the night games, its popularity paying off for Wilkinson, who correctly surmised that just as “talkies saved the movies, lights would save baseball.”16

The excitement over night baseball, however, did not preclude the local press from salacious race baiting when discussing it. In one postgame report, W.R. Beaumier, sports editor of the Express, wrote that he had “overheard” a Negro talking about the lights. The man in question allegedly commented, “I don’t like the idea of that night baseball. When one of those boys starts for second base his shadow’s gonna follow him right down the baseline and the umpire’s not gonna know who’s who.”17 In spite of such a hateful mischaracterization, San Antonio was clearly impressed with the operation, and its Texas League Indians were playing under lights the next season.

Harris batted .333 in 1930, catching a majority of the Black Indians games through the summer, yet by the second week in August, he was no longer in San Antonio’s lineup. Perhaps he was injured or jumped his contract, though there is no record of either. In any event, Harris was back for his third turn with the club in 1931.18 During the offseason, Harris had remained in San Antonio, where he resided in a boarding house at 572 Dawson Street with his wife, Roselea. Curtis was five years his wife’s senior, the two having wed when they were in their teens. On the population census taken that fall, Curtis listed himself as a “professional baseball player,” noting no other income; his wife did not hold a job. He also listed himself as a World War I veteran, though he would have been too young at the time. Roselea was from Louisiana, as were her parents, and she lived until the day after Christmas 1980, when she died at Houston’s Memorial Hospital. Harris had long separated from Roselea by this time, marrying Ruth Wilson in 1936, Olice Martin in 1940, and Rebecca Harris sometime before 1947.19

In 1931 the Black Indians went through an organizational change at the end of May that portended big things for Harris and Beverly, the two players the new management could most likely sell off as it restructured the club. Cullen E. Taylor was the organization’s new president, with George Holley coming in to take over as manager. Holley was quick to assure the community that the Black Indians would be a “well-disciplined team,” and one that would do everything it could to win. Beverly, “the fork-handed black hurler,” had won his way, not only in the hearts of the colored baseball fans of the city, but also the white patrons, who “flocked to see the locals.” Whenever Beverly was on the mound, Harris was behind the plate, the battery becoming a tandem of certain merit.20

In early June the Black Indians announced that a set against the New Orleans Pelicans would be the last played by Beverly and Harris, both sold to the Kansas City Monarchs for “a reported sale price” of $750. In their last game with San Antonio, the pair did not disappoint as Beverly scattered six hits and struck out five for the win while Harris doubled in a run and scored another in a 3-2 triumph that pushed San Antonio to the top of the Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana League standings. In besting New Orleans, they also beat the battery that would take their place with the Indians a few days later, Pelican left-hander Foster, said to be a nephew and protégé of Rube Foster, and Willie Dilworth, a catcher. For Beverly and Harris, it was the kind of swan song every player hopes for. 21

Within the week, Harris was playing third base for the Monarchs as they took the measure of the Racine Seft’s Belles, 5-0. At the plate, he came through early when with a 1-0 lead in the top of the second, he turned on the first pitch offered, a fastball, belting the longest homer “ever seen … in Athletic park in the past nine seasons of baseball.”22 One observer noted that it was “way in the air, looking like an easy out – but that ball kept traveling, and when it landed half way from the hedge to the tennis courts the fielder was nowhere near it.”23

In mid-August the Monarchs headed to Pittsburgh to take on Cum Posey’s mighty Homestead Grays. The Grays were widely considered the best black team on the planet that season. Posey’s squad featured five future Hall of Famers, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Joe Williams, Jud Wilson, and Willie Foster, as well as others deserving of consideration, such as George Scales and Ted “Double-Duty” Radcliffe. For their part, the Monarchs had scuffled somewhat, at least considering the standards set the previous year, because certain regulars – Chester Brewer and others – had been playing in Minnesota. With their return as well as the addition of newcomers like Harris and Beverly, the Monarchs were believed a tough team to beat.24

Having made the trip with the Monarchs, Curtis Harris inexplicably finished the season in Pittsburgh with the Crawford Giants. His lone recorded plate appearance came in the first game of a doubleheader at Baltimore against the Black Sox, a 4-2 victory in which he went 1-for-4 while playing left field.25 Harris’s combined 1931 offensive numbers with Kansas City and Pittsburgh were comparable to those he had put up in Texas as he hit .283, with a .333 on-base percentage, in 53 at-bats (17 games). With Harris, however, his offense was negligible when compared to the value he brought as a utilityman. In 1931 Harris played first base most of the time, but also played third base, left field, and shortstop. His league fielding percentage was remarkable, reflecting only a single error, that coming at first base where he was known to flash some classy leather. Harris was carving a multifaceted role for himself as a player, one that stayed with him throughout his playing career.

In 1932 Harris remained in the East with a number of his teammates, at least for a time, as he began the season with William “Pimp” Young’s Cleveland Stars in the East-West League. The idea was that the players would play for the Stars through the fall and then regroup with the Monarchs in the winter for a tour of Mexico and the West Coast. Regarding the Stars, Pimp Young was said to be the “prized optimist of the world,” an owner who would do whatever it took to establish a strong team in Cleveland.26 Harris was joined in Cleveland by his Texas batterymate, Charley Beverly; Dink Mothell; veteran right-hander Nelson Dean; and Branch Russell, longtime member of the St. Louis Stars. The East-West League’s ambitious first-half schedule called for each of its eight teams to play 56 games by July 3, with the second half beginning on the July 4 holiday weekend.27

In spite of Young’s optimism, Cleveland stumbled out of the gate, winning just two of its first 10 games, including being swept in an early-season three-game set by Homestead. They went on a brief run in early June, posting four wins against a single loss, improving to 6-13, before dropping two more to stand 7-15 by the middle of the month. The team was hurt by the defection of Charley Beverly, who had jumped to the Pittsburgh Crawfords as Gus Greenlee sought to field a team of game changers for his splendid new ballpark.

Scheduling 56 first-half games and getting them played were two different things, especially during the Great Depression. The year 1932 proved to be the bottom of what had been a three-year death march for the nation’s economy, one that saw a quarter of American breadwinners out of work. The depressed conditions and a lack of publicity manifested themselves at the East-West League turnstiles, and by midseason a majority of the team owners ceased paying monthly salaries to players, canceled the remainder of first-half games, and consolidated the league to six teams. In return, these same owners witnessed many of their players jumping contracts. Pimp Young was quoted in the press as having spent years saving money, only to see it burn now in a matter of days. For their part, the players, many of them with families to think of, could not afford the lack of security the league now offered.28

Not all team owners were making cutbacks. J.L. Wilkinson with the independent Kansas City Monarchs had planned to begin organizing his team in December, after the Eastern Colored League and other circuits had finished their respective seasons. This made sense as many of his returning players were currently in the ECL. Once organized, he planned to take his Monarchs on a tour of Mexico and the West Coast, playing all who would pay to face his “traveling circus.” Upon hearing of the salary stoppage, however, Wilkinson moved to gather his flock, sending out word that the time to begin was now. In short order, George Giles, Charlie Beverly, Newt Allen, Tom Young, and Willie Wells left the Crawfords for Kansas City, with Curtis Harris, Dink Mothell, Chester Brewer, and others joining them. W. Rollo Wilson, sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, praised Wilkinson for the concern shown his players. His actions, unlike those of certain ECL owners, elicited the “loyalty of players” rather than disdain. Kansas City opened its 1932 campaign on the road in Chicago on July 10, with Harris listed on the roster as a utility player.29

In late July the Monarchs traveled to Winnipeg for an exhibition. The team was well announced as a “Colorful Club,” one that was spoken of highly by sportswriters for their “sportsmanship and the fast ball this great club” was capable of playing. A local wag also marveled as the wizardry of the team’s preliminary practice, in which they dazzled the crowd with an uproarious game of “shadow ball in which they solemnly went through all the motions of throwing, catching and hitting a purely imaginary baseball.” The laughing stopped the next day as the Monarchs, one of the “classiest outfits ever seen in Winnipeg,” breezed to a 14-1 victory over the Winnipeg All-Stars. Bert Hunter was the story, mixing a “dazzling speed ball with a fast-breaking curve” to stymie the locals, allowing a scant six hits, while striking out 14. At the plate, Willie Wells blasted a homer to center; Bell and Dink Mothell added three hits each, and Harris, playing right field, had two hits and scored two runs.30

With summer nearing an end, it was reported that the Monarchs, as well as the Black Lookouts and the Fort Worth Black Cats, would go to Mexico City to play a series with the Mexico City Aztecs. The Monarchs, “advertised as the colored champions of the world,” were to perform in the city from October 22 to November 8.31 Besides the Mexico City Aztecs, the Monarchs also played against a top Mexican baseball club named the Galos. Kansas City acquitted itself quite well on the road swing, winning 19 games against a single loss. As for Harris, he was just entering the prime of his career. He finished 1932 in Kansas City with a combined .242 batting average and .318 on-base percentage, while playing first base, catcher, and outfield. Over the next year, Harris began to play for Gus Greenlee on the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team loaded with Hall of Fame skill and on the cusp of becoming one of the great teams in the game’s history.

In The Forgotten Players, Robert Gardner and Dennis Shortelle note that by 1933, Gus Greenlee had spent way too much time and money on the road and that the team’s barnstorming schedule was “playing havoc” with his investment. Greenlee concluded that if the black game were to become a “paying proposition and regain the credibility lost” in the post-Rube Foster years, it required “reorganization and resolute leadership.” He determined to bring back the old Negro National League, only with Depression-era prices to attract struggling fans. By the start of the 1933 season, Greenlee’s Crawfords were joined by Cum Posey’s Homestead Grays, the Detroit Stars, Columbus Blue Birds, Indianapolis ABCs, and Chicago American Giants to form a second Negro National League. Although many of the new club owners were “numbers men” and local racketeers, they represented a new breed of Negro baseball men with shrewd business instincts, who brought more financial stability to the enterprise. The league lasted until 1948, two full years after Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers initiated the major leagues’ “Great Experiment” to integrate baseball. In the league’s first year, Greenlee’s Crawfords went 40-21-2 in league play and won the championship.32

Where Curtis Harris may have played in 1933 – if he played – is unknown; however, by 1934 he was with the Crawfords. As the club’s principal utilityman, he played everywhere – catcher, first base, second, shortstop, right and left field – and posted a combined fielding percentage in excess of .967. Harris’s primary position that season was catcher, where he backed up the young Josh Gibson, who was coming into his own as the game’s finest catcher and wielded a prodigious bat. When not spelling Gibson, Harris filled in for Oscar Charleston at first base. The 1934 lineup also featured the inimitable Satchel Paige. Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson were there as well, along with Vic Harris, Ted Page, Chester Williams, Leroy Matlock, William Bell, and Sam Streeter. With five future Hall of Famers, a barn full of arms, and a jack-of-all-trades, the 1934 Pittsburgh Crawfords proved to be a formidable club.

The Crawfords began the season by taking two out of three from the American Giants in Chicago in mid-May. A week later, they opened their home season, taking two of three from the Philadelphia Stars. With Pittsburgh Mayor William McNair tossing out the first pitch, a slow bender, Charleston led the way for the Crawfords, poling two long homers in the wins. The Crawfords finished the month by sweeping the Bacharach Giants in four games.

On July 4 in front of a great holiday crowd at Greenlee Field, the Crawfords took the measure of their crosstown rivals, the Homestead Grays, 4-0. Satchel Paige allowed just two baserunners while no-hitting the vaunted Grays offense and striking out 17. When later asked the secret of his success, a “smiling Satchel” confessed that he had not realized it was a no-hitter until the final frame. He said it was his first no-hitter with Pittsburgh, but that he had thrown a couple in Chicago. It was reported as being the first time the Grays had been held hitless, “something unheard of before.” The Grays fought back in game two, saving the holiday dip, 4-3. An announced crowd of 11,608 witnessed the two games at Greenlee Field, surpassing the previous park record by 5,000.33

The league announced that the second annual East-West All-Star Game would be held on August 26. As the early ballots were posted, Curtis Harris was listed on it as a catcher, yet a few weeks before the game, he was in second place in the voting for a utility spot, 142 votes behind the Black Yankees’ Rev Cannady. This came in spite of the fact that he had been a nonentity at the plate, batting a scant .192 to that point in just nine games. The lack of playing time could have come from his having been suspended “indefinitely” by Gus Greenlee, along with Chester Williams, for “conduct unbecoming ball players and gentlemen.” The suspension cost him because he ultimately fell to fourth in the voting and missed out on the East-West game, which was played in front of 30,000 people at Comiskey Park and was won by the East, 1-0.34

While Chester Williams was back in the lineup quickly, Harris played little after an early-August dip against the Bacharach Giants, one the Crawfords dropped and in which Harris went hitless. He was hitless again in a game at Hightstown, New Jersey, an 11-10 win over the local nine. 35 As the Crawfords marched toward a league championship, Harris was a nonfactor. Box scores in the Pittsburgh Courier do not list him again after the series with the Bacharachs. Harris pinch-hit in a game against the Black Yankees in mid-September, but was hitless in in Pittsburgh’s 10-8 win.36 What other playing time he received may have come via weekday games against nonleague opponents. Harris is recorded as playing in 34 games that season and hitting .248 in 101 at-bats. It was his best season to that point, suspension or not, and set the stage for the following year in Pittsburgh.

The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords were down a Hall of Famer from the year prior as Satchel Paige opted to pitch in Bismarck, North Dakota, before joining the Kansas City Monarchs, a team for which he ultimately pitched parts of eight seasons. Even without him, the Crawfords were a formidable squad that boasted future Hall of Famers Bell, Johnson, Gibson, and Charleston, the veteran warhorse who as player-manager was still a presence. The roster also included position players Harris, outfielder Sammy Bankhead, Pat Patterson (a 23-year-old switch-hitting second baseman), Jimmie Crutchfield, Chester Williams, catcher Bill Perkins, and rookie infielder Ted Bond. Pitchers Leroy Matlock, Roosevelt Davis, Bert Hunter, Sam Streeter, Bill Harvey, and Ernest “Spoon” Carter, each of whom pitched in at least nine games and hurled more than 50 innings, fronted the staff. Harry Kincannon pitched over 30 innings, and the veteran William Bell and even Josh Gibson toed the rubber. Matlock, the veteran lefty, led the staff with an 8-0 record and a 1.52 ERA.

At season’s outset, it was clear that the Crawfords would be a team to reckon with, along with the Philadelphia Stars and Chicago Giants.37 A club not listed in this prediction was Alex Pompez’s New York Cubans. Led by Martin Dihigo, the finest Cuban player of all, the Cubans had an outstanding roster. Having been nudged out in a 3-2 thriller the weekend before, the Cubans came to Pittsburgh “with blood in their eyes,” ready to play ball.38 Amid the “fanfare of martial music,” local dignitaries and the “social firmament,” 6,000 fans witnessed baseball at its “unadulterated best.” The two evenly-matched clubs fought it out in close games throughout the set, the Crawfords winning games one and two, 6-5 and 2-1, while tying games three and four, 4-4 and 3-3. The series left Pittsburgh with a 6-0-2 record in the young season.39

Later that week the Crawfords took the measure of the Chicago Giants, winning game one 10-2 at Eagle Park in York, Pennsylvania, before taking two out of three in a weekend set at Greenlee Field. In the first game, Sam Streeter “hurled great ball,” fanning 12 batters, while Harris had a double and single, Bell a triple and double, and Gibson a home run. Curtis Harris, on for Charleston at first base, was making his first recorded appearance of the season.

As the Crawfords streaked to the 1935 league crown, besting the New York Cubans in the championship set by four games to three, Harris contributed career highs in games played (36), batting (.359), RBIs (27), slugging (.530), OBP (.414), and OPS (.944). He played everywhere for the Crawfords that season, even pitching, as he did in June when he was called from the bullpen against the Bushwicks in a 7-0 loss. He came back in the following game at first base, going 1-for-3 in an 8-1 win. In the second game of a July doubleheader against the Brooklyn Black Eagles, Harris went 3-for-4 with a homer while playing first and second in a 12-11 loss. (The Crawfords won the opener, 5-3.) With Gibson, Charleston, and Chester Williams entrenched starters, Harris generally came on during the second game of twin bills, or as a pinch-hitter, as he did in a Labor Day split with the Grays, when he entered the game late to belt an RBI double in a 15-11 win. It was Curtis Harris’s last season with the Crawfords. His performance opened opportunities for more playing time and in 1936 Harris and Crawfords teammate Andrew “Pat” Patterson both signed to play with the Kansas City Monarchs.40

In 1936 Harris traveled on more than one occasion with the Monarchs to Manhattan, Kansas, just over 100 miles away, to play various area clubs. Such was the case when in mid-May they faced the Chastains at Manhattan’s Griffith Field. Scoring in every inning except the second and ninth, the Monarchs strung together 16 hits, six for extra bases, along with nine Chastain errors, to win 15-3. Harris, who was playing first base for the Monarchs, was 2-for-5 with two stolen bases. Throughout the contest, a group of “colored folk” cheered for the Monarchs, chanting, “Gee they’re sweet. Gee they’re sweet. Those Kansas City Monarchs can’t be beat.”41

It was in also Manhattan that Curtis Harris met his future wife, Ruth Wilson, born on April 14, 1917, to Harry and Etta (Pitts) Wilson in Manhattan. She frequented ballgames with friends, especially if the Monarchs were in town. While nothing is known about how they met, the two were married on October 5, 1936, in Jackson County, Missouri following Curtis’s final season with the Monarchs.42 Curtis was 34 at the time and Ruth 19. They eventually had one child, Curtis E. Harris Jr. According to Ruth, while Harris and the other Monarchs had it “pretty rough” traveling all of the time, and often through the segregated South, “they could sure play ball.” She opined that had the big leagues been taking blacks at that time, Curtis Harris and the others would have been there.43

The Monarchs set the tone that season, turning out large crowds at every stop and entertaining fans with their skill and gamesmanship. Whether in big cities like Chicago or small burgs like Pampa, Texas, the Monarchs were there both to win and to please. They had been on the road since March and so it is little wonder that they toyed with the crowd when they had a chance. Newt Allen, “the Eddie Collins of colored ball,” was a “fast fielding second sacker,” who enlivened games with his “uncanny” throws made from any position. Curtis Harris was “the comedian and the noisy player of the club.” While at first base, Harris was snatch-happy, “giving the fans many a thrill with one-handed stops and trick plays.” One of the Monarchs’ “pet stunts” was to get men on first and third and work a double steal. Some of their opponents that season could only scratch their heads, thinking it was all done “with mirrors.”44

In late August the Monarchs returned from the Pacific Northwest, where they had pasted a pair of Spokane teams of the Idaho-Washington League by scores of 11-3 and 12-3, to prepare for the East-West All-Star Game at the end of the month at Chicago’s Comiskey Field. As a tuneup, they took on the Blues of Madison, Wisconsin. The Blues were a white semipro squad, and while the Monarchs managed to beat them in the opener, the Blues fought back in the second game, winning 7-5. It was a rare Kansas City misstep, but they had been ambushed by a special competitor, one who the year before had led golf’s US Open before fading to sixth. Alvin “Butch” Krueger was a 29-year-old professional golfer, and one of the most sought-after endorsements on the professional golf tour. He also played baseball. Krueger had pitched in the American Association with the Milwaukee Brewers and with his newfound golf cachet enjoyed a large following in the area. In the game Butch struck out five Monarchs, holding them scoreless after the first inning for seven frames, before the Monarchs struck for three in the ninth, though falling a tally short. The crowd was ecstatic, carrying Krueger from the field. Harris, batting second rather than his customary fifth or sixth, went 1-for-4.45

A probable lineup for the East-West Game was released in August, naming Harris as a first baseman for the West. It was the first time that Popeye, as he was increasingly being called, had earned such a honor. The game, played in front of 30,000 fans, was a mismatch as the East put it on the West, 10-2. While many of the players performed at “Big League Calibre,” Satchel Paige was “the Magnet,” who drew thousands of fans to watch him play. “Long, tall, dark,” and with an aura that “sets him apart,” Paige had proven his worth over hundreds of ball fields and the big leagues were well aware of him. “Everywhere baseball is talked,” wrote William Nunn in the Courier, “they speak of Satchel Paige.” By the time Paige entered the game in the seventh inning, however, things were decided, with the East up 8-1.46

The Monarchs were billed as the top independent team in the country in 1936. It was a ballclub with five future Hall of Famers: Bullet Joe Rogan, Willard Brown, Hilton Smith, player-manager Andy Cooper, and owner J.L. Wilkinson. The Monarchs changed the way franchises of their merit did things. Rather than grapple with the politics and league issues in the East that plagued organized black baseball year after year, they stayed on the road and played all comers. Harris finished the year batting .294, with a .308 OBP and a .700 OPS. Although he married Ruth that autumn, he chose not to settle in Kansas City and headed east to play with the Philadelphia Stars of the National Negro League. He had some of the best seasons of his career in Philly, batting .309 and .305 in consecutive seasons and playing in more games than he had played since arriving out of Texas, before quickly fading out after the 1939 season.

With Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars, Harris was playing with a cast of characters that, while familiar to him, were new as teammates. Future Hall of Famer Jud Wilson manned first base while other veterans including Dewey Creacy, Ted Page, Paul Dixon, and Larry Brown were at third, in the outfield and behind the plate respectively. Youth came in the form of center fielder Gene Benson and Slim Jones, a 24-year-old pitcher who also played first base. Jones would lead the Stars in hitting that season with a .333 mark, but as young as he was, his career was already declining. Just three years earlier, after going 21-6 with a 1.24 ERA and 185 strikeouts, Jones was considered by some to be as good as Satchel Paige, but drinking ruined him.47

Harris played wherever he was needed, though early on he mainly spelled Wilson at first. In a May doubleheader loss to the Newark Eagles, 8-6 and 11-2, Harris played first, garnering three hits in game one. A week later, he had three hits against the Crawfords. It was a close affair in which each team had 16 hits, but the Crawfords rallied for two runs in the ninth to take it, 11-9. The Pittsburgh squad was not the team it had been in previous years, as many of its star players had gone south to play in the Dominican Republic. The Stars, having lost Turkey Stearnes and others to Santo Domingo as well, were able to generate some offense and flash enough leather to see their fortunes uptick. In an early July 6-2 victory over the West York Firemen, Harris shined in the field even though he went hitless.48

With the first half ending, the Grays, behind the league-leading hitting of Buck Leonard, were winning it going away. Pops Harris, as the Pittsburgh Courier called him, was fourth on the Stars in batting, and near the top of the league at .336, just behind his old teammate Vic Harris. Coming out of the turn, the Grays traveled to Philadelphia to face the Stars, winning both ends of a league doubleheader, 10-6 and 12-4. With the score tied 6-6 in game one, the Grays scored four runs in the 10th. The Stars pushed on. By mid-August, Harris was increasingly playing second base, as he did in a nonleague game against Allentown, the Eastern Pennsylvania League’s league-leading club. Still playing second, Harris garnered three more hits in a sweep of the Bushwicks, 10-0 and 2-0, before 6,000 fans at Dexter Park in Queens.49

The Stars finished the season by defeating the Washington Elite Giants, 4-2 and 9-3, to clinch third place. A few days later, the Stars took on the New York Black Yankees in Asbury Park, New Jersey, losing 4-2. The Black Yankees’ Johnny Stanley held the Stars to three hits, striking out 12. Harris, playing first base, had one of the three hits. It was a fitting end to what was perhaps the most complete season of Curtis Harris’s career. He had again shown improvement across the board, from games played (36) to batting average (.309) to h OPS (.801), though his home run total fell to a single tally, and he was set to do even more the following year.50

Ed Bolden flipped his All-Star roster to an extent in 1938, but the Stars were still considered contenders. In May they squared up against a tough semipro club, the Strand Billiards, in Vineland, New Jersey. In front of a “fairly large” and festive crowd, one that saw Mayor John C. Gittone toss out the first pitch, the Stars romped to an 11-1 victory. The Billiards had a good team that season, but in the face of “21 hits for 29 bases,” the Stars left little doubt as to who was the better squad. In a rare outing for Harris that season, he went hitless in four at-bats while playing second. The Stars, however, stumbled against another semipro team the following week, the Red Bank Pirates, who behind the 10 strikeouts of local ace Al Caruso topped the Stars 3-1. Harris had one of the Stars’ seven hits.51 In spite of an up-and-down season, the Stars were still in second place before they stumbled against the Newark Eagles and split a pair with the Grays. Inconsistent performances in important moments led to Philadelphia’s downfall, and rather than closing the gap they drifted to another pedestrian third-place finish at 37-31-3.52

Harris finished the campaign having played a career-high 55 games and batted .305 with 37 RBIs and a career-high .815 OPS. Harris played one more season in Philly, primarily in a reserve role, but his numbers dropped to .282 and .590 OPS. He left the Stars in the middle of 1940, joining Cool Papa Bell and over 200 other former Negro Leaguers in Mexico. Harris and Bell signed with La Unión Laguna de Torreón. In a mere eight games in Mexico, Harris batted .281 with nine hits and five RBIs in 32 at-bats, scored 10 runs and had a .324 on-base percentage.53

Upon his return from Mexico, Curtis Harris married again, this time to Olice Martin. The two were wed in Washington County, Texas, on July 8, 1940. There is no record to indicate when Harris would have divorced his second wife, Ruth, if he divorced her, but his Texas marriage license indicates that he was authorized to be married in that state. In that same year, Olice gave birth to a son, Curtis Kenneth Harris. Where the family lived is unknown, but after he batted .154 in 41 plate appearances with the Stars in 1940, Harris’s career ended. His draft registration card for World War II, dated June 24, 1942, has him living initially in Houston, Texas, but the address was later amended to Los Angeles. The registration certificate also listed his mother, Vinia Taplin, who was still living in Burton, Texas, as the person who would always know his address. Curtis listed his employer as the C.A.A. Municipal Airport in Houston. Perhaps most importantly, Harris asserted in this document that he was 40 years old, having been born in Washington County, Texas, on February 14, 1902.54

By 1947 Harris was residing in the Watts section of Los Angeles, where he was working in construction as a concrete laborer. He was living with Rebecca Harris, who identified herself as his wife, though no official marriage certificate is found. On August 3, 1947, at 8:00 A.M. on a Sunday morning, Curtis Harris was brutally murdered. According to the Los Angeles County medical examiner, he suffered a hemorrhage after being “stabbed with a knife” in the neck at a residence in Willowbrook, Los Angeles County. While his death was recorded as a homicide, there was no report of it in the Los Angeles newspapers, which was common for the deaths of murdered minorities. His body was initially taken to a local funeral parlor before being sent for burial to an African-American Cemetery in Cameron, Texas. After years on the road, Curtis was finally home.55

Curtis Harris lived a life that was no doubt difficult at times, but had its moments. He was the “comedian” on a number of his teams, and his marriage record indicates that he was perhaps difficult to hold down. Like ballplayers of any generation, he was a traveling man, and no doubt that led to certain indiscretions and behaviors that would be difficult for any wife to accommodate. In the end, Curtis Harris was an instrumental player on some of the great baseball teams in blackball history, playing a utility role that his good nature was perhaps better suited for than others might have been. When afforded the chance for more playing time, as in Philadelphia, he came through at an exceptional level, at least as long as his legs could carry him. If Curtis Harris was indeed 45 years-old in 1947, then he had given life and the game quite a run.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, Seamheads.com was used for all Negro League player statistics and team records.

Notes

1 Phil S. Dixon. The Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour: Race, Media, and America’s National Pastime (Lanham, Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2019), 194.

2 His birthdate remains a matter of contention. Seamheads and Baseball-Reference.com recognize the date provided on his 1936 marriage license and that in the 1910 Federal Census, 1905. On his World War II draft card, however, perhaps the last official document signed by Harris, he gave his birthdate as 1902. It was also the date provided in the Los Angeles coroner’s office death certificate. His headstone in Cameron, Texas, shows 1907. For purposes of this essay, 1902 is the accepted date, again, because it is the last date he personally provided on a federal document, as well as the one provided on his death certificate.

3 1900, 1910 and 1920 US Census, Washington County, Texas, population schedule; Ancestry (ancestry.com); Certificate of Death, Texas Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, #15648, Vinah Taplin, filed April 6, 1948.

4 “Black Barons Take Um’ All From Meridian Giants,” Birmingham Reporter, April 24, 1926.

5 Birmingham Reporter, April 3, 24, and May 1, 1926.

6 Birmingham Reporter, May 8, 15, 22, and 29, and June 12, 1926.

7 Birmingham Reporter, September 18 and 25 and October 2, 1926; Pittsburgh Courier, October 9, 1926; William J. Plott, Black Baseball’s Last Team Standing: The Birmingham Black Barons, 1919-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019), 62-64.

8 See Atlanta Constitution, May 3 and 4 and June 14, 1927; Nashville Tennessean, May 22 and 23, 1927; Chattanooga Daily Times, May 15, 1927; Mount Carmel (Illinois) Daily Republican Register, August 29, 1927.

9 “Grays Win Final Game of Series,” San Antonio Express, July 8, 1930.

10 The “Black Indians” as opposed to San Antonio’s “White” Indians of Organized Baseball’s Texas League. There is also no evidence to support Curtis Harris having been in Houston with Patterson prior to the 1929 season.

11 “Black Indians Get Three New Players for Galveston Series,” San Antonio Express, June 26, 1931; 1930 US Census, Bexar County, Texas, population schedule, Ancestry.com.

12 Harris may have made more than five appearances as a pitcher in 1929, but available box scores cannot prove it. San Antonio Express, April 21, May 1, June 25, July 8, and July 29, 1929.

13 “Black Indians Rally to Beat Black Giants,” San Antonio Express, April 21, 1929; “Black Indians Clean Up on Dallas Giants,” San Antonio Express, April 23, 1929.

14 “Black Indians Go Twelve Innings to Beat Black Sports,” San Antonio Express, July 29, 1929.

15 “Negro Clubs Will Play Baseball Here by Electric Light,” San Antonio Express, April 29, 1930; Charles F. Faber, “J.L. Wilkinson,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org.

16 “Night Baseball in Debut Here: Huge Portable Plan Attraction Itself,” San Antonio Express, May 2, 1930.

17 See reports in San Antonio Express, April 30 and May 2, 6, and 19, 1930.

18 San Antonio Express, August 10 and 19, 1930.

19 1930 US Census, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas, population schedule; Ancestry.com; Missouri, Jackson County Marriage Records, Application No. 64566, October 5, 1936, Curtis Harris and Ruth Wilson; Ancestry.com; Texas, Washington County Marriage Records, license filed July 10, 1940, Curtis Harris and Olice Martin; Ancestry.com. Texas divorce records for the time period before 1968 are not readily accessible.

20 “Ebony Tribe Wins from Black Bison,” San Antonio Express, May 31, 1931; “Black Indians in Winning Stride,” San Antonio Express, June 2, 1931.

21 “Black Indians Meet Black Pels Tonight,” San Antonio Express, June 24, 1931; “Black Indians Beat Pels, 3-2,” San Antonio Express, June 25, 1931; “Black Indians Get Three New Players for Galveston Series,” San Antonio Express, June 28, 1931.

22 “Colored Boys Win from Racine Team,” Racine News Journal, July 10, 1931.

23 “Colored Boys Win from Racine Team.”

24 Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1931.

25 Pittsburgh Courier, September 19, 1931.

26 Pittsburgh Courier, June 4, 1932.

27 Pittsburgh Courier, April 30, 1932.

28 Pittsburgh Courier, June 4 and July 2, 1932.

29 “‘Kay See’ Monarchs Back in Harness,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1932. Courier sportswriter W. Rollo Wilson exuberantly promised that “Full Accounts” of Monarch games would be published in that paper each week, yet after July 16 the Monarchs were not mentioned in the Courier for the rest of the year.

30 Winnipeg Tribune, July 21 and 23, 1932.

31 A flyer was posted in various newspapers advertising the series. See Chillicothe (Missouri) Constitution-Tribune, September 15, 1932; Ruston (Louisiana) Daily Leader, September 13, 1932; Macon Chronicle-Herald, September 26, 1932; and El Paso Herald-Post, August 19, 1932.

32 Robert Gardner and Dennis Shortelle, The Forgotten Players: The Story of Black Baseball in America (New York: Walker and Co., 1993), 34-35; Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

33 Pittsburgh Courier, July 7 and 14, 1934

34 Pittsburgh Courier, August 4, 11, and 25 and September 1, 1934; Ryan Whirty, “Lake Charles’ Link to Negro Leagues History,” americanpress.com/news (Lake Charles, Louisiana), August 8, 2013. Ryan Whirty explains how Williams was shot to death on Christmas night 1952 in his own Lake Charles night club. Williams was reported to have been shot five times, twice in the left arm, twice in the neck, and once in the foot. Police arrested a Tom Scott, who was taken to the local hospital with icepick wounds inflicted by Williams in a brawl.

35 Pittsburgh Courier, August 11, 1934; “Hightstown Nine Loses Thriller, 11-10,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, August 2, 1934.

36 “Pittsburgh Crawfords Top Black Yankees, 10-8.” Asbury Park Press, September 22, 1934.

37 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 12, 1935.

38 “Cubans, Crawfords Opener Here Holds Spotlight,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 11, 1935.

39 Pittsburgh Courier, May 18, 1935.

40 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1935; Brooklyn Times Union, July 15, 1935; New York Age, September 7, 1935; Pittsburgh Courier, September 7, 1935.

41 “Monarchs Win in Easy Manner,” Morning Chronicle (Manhattan, Kansas), May 20, 1936.

42 Divorce records involving Curtis Harris and his first wife, Roselea Harris, have not been found.

43 Missouri, Jackson County Marriage Records, Application No. 64566, October 5, 1936, Curtis Harris and Ruth Wilson; Ancestry.com; Ruth Wilson Bayard interview, Manhattan (Kansas) Mercury, February 12, 1984. Ruth Wilson Bayard Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

44 Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, June 11, 1936.

45 Salt Lake Tribune, July 7, 1936; Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), August 22, 1936; Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker & Company, 2012), 71.

46 “Satchell Paige is Magnet at E-W Game; Players of Big League Calibre Perform,” William G. Nunn, Pittsburgh Courier, August 29, 1936.

47“Slim Jones,” baseball-reference.com.

48 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 1937; Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), June 2, 1937; York (Pennsylvania) Daily Record, July 2, 1937.

49 Pittsburgh Courier, July 10 and 17, 1937; Daily Record (Long Branch, New Jersey), August 7, 1937; Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), August 11, 1937; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 13, 1937.

50 Philadelphia Inquirer, September 12, 1937; Asbury Park Press, September 14, 1937.

51 Daily Journal (Vineland, New Jersey), May 14, 1938; Daily Record (Long Branch, New Jersey), June 4, 1938; Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1938.

52 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 15 and 28, 1938; Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), August 25, 1938.

53 Twitter.com, “Algodoneros UniónLaguna Verified,” March 30, 2019; Baseball-reference.com

54 Draft Registration Card, #1933, Order #11,509, D.S.S. Form 1, June 24, 1942.

55 Certificate of Death, State of California, County of Los Angeles, date filed: August 13, 1947.

Full Name

Curtis Taplan Harris

Born

February 14, 1905 at Washington County, TX (US)

Died

August 3, 1947 at Los Angeles, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.