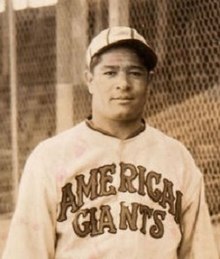

Larry Brown

“One of the most durable and dependable catchers in the Negro Leagues era, Larry ‘Iron Man’ Brown was a master behind the plate, yielding a quick release and an arm to be envied.”1 Brown never pulled his mask off for a pop fly. Never staggered under foul balls like other catchers. Brown described the art to fellow Negro Leaguer Joe Greene of the Kansas City Monarchs: “the English on the ball, makes the ball do a figure eight in the air. It seems like the ball is going away from you, but it will come right back to you.”2 An expert at his craft, his legacy gets lost in the shadows of fellow catchers Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, and Louis Santop. Brown participated in seven East-West All-Star Games and played for teams that won championships in the Colored World Series and Negro American League. His career spanned more than a quarter-century, and he made more appearances behind the plate than any other catcher in Negro Leagues history except Frank Duncan.3

“One of the most durable and dependable catchers in the Negro Leagues era, Larry ‘Iron Man’ Brown was a master behind the plate, yielding a quick release and an arm to be envied.”1 Brown never pulled his mask off for a pop fly. Never staggered under foul balls like other catchers. Brown described the art to fellow Negro Leaguer Joe Greene of the Kansas City Monarchs: “the English on the ball, makes the ball do a figure eight in the air. It seems like the ball is going away from you, but it will come right back to you.”2 An expert at his craft, his legacy gets lost in the shadows of fellow catchers Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, and Louis Santop. Brown participated in seven East-West All-Star Games and played for teams that won championships in the Colored World Series and Negro American League. His career spanned more than a quarter-century, and he made more appearances behind the plate than any other catcher in Negro Leagues history except Frank Duncan.3

One of Brown’s contemporaries, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, referred to him as one of Black baseball’s outstanding backstops, who could “catch a cutball, knuckleball, emeryball, anything.”4 In 1930, the Pittsburgh Courier’s William Nunn wrote, “Larry Brown, be it known, ranks with the greatest receivers of this or any other age. He’s the personification of grace, finish, and brains. He can throw like Biz Mackey, receive to the queen’s taste, and has a wonderfully steady influence on the twirlers. This boy is ranked with the best we’ve seen.”5 At the heart of this biographical sketch is the story of one of the game’s finest forgotten catchers.

Ernest Larry Brown was born on September 5, 1905, in Pratt City, Alabama.6 His parents, Charlie Brown and Viola Brannin, had one daughter, Daisy, in 1904. Larry was raised by his mother, a domestic, and did not know his father, a white man about whom little is known.7

Pratt City was predominantly populated by people from across the South, northern industrial centers, and foreign nations who came to work in the Pratt Mines, a source of coal for Birmingham’s booming steel industry since the late 19th century. This Southern salad bowl of ethnic industrial culture included black and white southerners, Englishmen, Scots, Irishmen, Frenchmen, Russians, Germans, and Austrians.8

Brown grew up in the all-Black Drifttrack neighborhood between Highway 78 and Avenue. As a young boy, he teamed up with future Negro Leagues pitcher Willie Powell on Pratt City’s youth baseball team. Brown developed his toughness and arm strength off the field by brawling with and throwing rocks at Powell.9 When Brown’s mother died in 1918, he began working for the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI) in Birmingham. He drove a cart pulled by mules to bring laborers to and from the job site.10

Brown was playing for TCI’s company team when the Knoxville (Tennessee) Giants, a Negro Southern League (NSL) club, lost two catchers to injury. When Brown put on his best clothes and went to the Dunbar Hotel to meet Knoxville’s manager, W.M. Brooks, the skipper looked at the 5-foot-7, 162-pounder and said, “Well, I’ll be doggone. You’re mighty small, mighty little.” When Brooks asked Brown if he thought he could handle Giants hurler “Steel Arm” Dickey, a 240-pound behemoth of a man, he replied, “Yes, sir, I think I can catch him.” The next day, July 4, 1920, Brown caught both ends of a doubleheader, and Brooks offered him $125 a month. With his mom deceased and his sister Daisy living in Philadelphia, Brown gladly accepted and began his professional baseball career.11

Brown remained with Knoxville until late in the 1921 season, when he signed with the Pittsburgh Keystones of the Western Independent League. In nine games, per Seamheads, he batted .367.12 In one contest against the Chicago American Giants, he threw out Jelly Gardner, Dave Malarcher, and Cristóbal Torriente on the base paths. Chicago manager Rube Foster told Pittsburgh’s Dizzy Dismukes, “One day, I’ll have him catch for me.”13

After the 1921 season, Brown returned to the NSL, this time with the Memphis Red Sox.14 However, his fortunes changed in 1923 when a former Keystones teammate was named manager of the Indianapolis ABCs, who competed in the Negro National League (NNL), a leading Black circuit. Dismukes had been impressed by Brown in Pittsburgh, so he signed him to back up George Dixon. Brown developed his defense by studying Dixon and working with Dismukes. The latter was a crafty right-handed submariner whose mastery of various curves considered trick pitches forced Brown to handle deliveries from multiple angles.15 Halfway through the season, Brown returned to Memphis – by then associate members of the NNL – to catch full-time.

Brown became a welcome addition to Memphis’s baseball fabric, remaining with the Red Sox through the 1925 campaign when Dismukes became the club’s manager. Memphis became not only Brown’s baseball home but a place where he thrived. As the young catcher honed his skills behind the plate, he earned acclaim as a calming force who kept things light as he controlled the game. Brown also enjoyed the lure of the nightlife on Beale Street, the Main Street of Black America for many in the South, where there was never a dull moment. His popularity on the field carried over to the bars on Beale, where he transformed into the life of the party, enjoying the nightlife and staying out until closing time.

The Memphis Red Sox returned to the NSL for the 1926 season, but Brown remained in the NNL with the Detroit Stars. After batting only .212 in 117 games over the previous three NNL seasons, he raised his batting average to .284 in 57 contests. That winter, legend has it that Brown was given a chance to join the American League’s Detroit Tigers after he cut down Ty Cobb on five consecutive stolen base attempts in the Cuban League. Years later, Brown told Negro Leagues chronicler John Holway “that Cobb came into the clubhouse and said ‘How would you like to stay down here and pick up on this lingua and come back to the states and pass as a Cuban?’”16 Brown responded, “Hell, I can’t do that, everybody knows me.”17

The Pittsburgh Courier published another version of the story in 1961, suggesting that Tigers owner Frank Navin offered Brown the opportunity to break into the major leagues by passing as a “white Cuban” following a two-year “retirement” from the Negro Leagues to the island. That article said Brown decided against it out of fear that Cobb would discover he was a Negro.18 (After Brown died, Memphis’s Tri-Sate Defender reported that he declined a similar proposal from the New York Giants in the 1930s, stating that passing for white would be a betrayal of his race.19)

Although Brown never did play in the segregated majors, he shined alongside some of baseball’s best over seven seasons of winter ball in Cuba, where he suited up for the Matanzas, Almendares, and Cuba clubs.20 With the Cuba club in 1927-28, his teammates included future Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, and Willie Foster.21 Brown enjoyed his best season statistically in Cuba in 1929-30, hitting .280 in 161 at-bats.22 When Brown became the Memphis Red Sox’s manager later in his career, his Spanish fluency proved useful, as Negro League teams signed more Latin players after Jackie Robinson broke AL/NL baseball’s color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Brown and his pregnant wife Anna Mae (Bransford), who accompanied him for the 1926-27 campaign, were treated like royalty on the island. Then, they took a boat back to the United States, where Larry Brown Jr. was born in Macon, Georgia, on May 9, 1927.23

Memphis was back in the NNL in 1927, so Brown returned to the Red Sox and batted .241 in 66 games. The team was dismal, however, and Brown and Memphis outfielder Nat Rogers joined the first-place Chicago American Giants (CAG) late in the season. In 13 regular season contests, Brown hit .344 to help Chicago return to the NNL championship series, where they defeated the Birmingham Black Barons to claim a second straight title. Facing the champions of the Eastern Colored League, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, in the Negro World Series, Chicago won the first three games. By the end of the first inning in Game Four, Brown had cut down four of five runners that attempted to steal against him.24 Although Brown had not homered in an official game all season, when the CAG finished off Atlantic City, 11-4, in Game Nine, he capped the scoring by taking Luther Farrell deep in the eighth inning.25

The Red Sox had sought compensation for the loss of Rogers and Brown; following the World Series, NNL President William Hueston ordered that the players be returned to Memphis.26

Prior to the 1928 season, the Martin brothers – four middle-class Black doctors – purchased the Memphis Red Sox.27 Unlike many Negro League owners, they never missed paydays, but they were tightfisted with salaries. As an everyday catcher in the prime of his career, Brown sought to make more money. He returned to the Chicago American Giants at the end of the 1929 campaign. When the CAG won five of seven contests against a team of American League All-Stars that fall, Brown appeared in five games and went 4-for-15.

In 1930, Brown joined the New York-based Lincoln Giants, a strong independent team led by manager/first baseman John Henry Lloyd that had formerly competed in the ECL and short-lived American Negro League.28 In July, Brown played in the first-ever game between two Black teams at Yankee Stadium.29 Brown was behind the plate during an 10-game postseason challenge series between the Homestead Grays and Lincoln Giants, five games of which were played at that ballpark. In one of those (on September 27), his counterpart, Josh Gibson, purportedly hit a home run completely out of the stadium.30 In a postgame interview, Brown and a teammate claimed that the ball landed inside the park. The Amsterdam News reported that the blast traveled 460-foot into the left-field bleachers, and the Baltimore Afro-American said: “it was the longest home run that has been hit at the Yankee Stadium by any player, white or colored, all season.” Negro Leagues historian John Holway concluded that the ball did not leave the park but instead went over the third tier of the upper deck down the third baseline.31 Nevertheless, such myths defined Gibson’s career and overshadowed Brown’s defensive prowess behind the plate.

The 1930 Lincoln Giants compiled a 41-14-1 record according to incomplete records. Brown appeared in 34 of those games and batted .311. But the team played much more frequently than that. Brown reportedly caught 234 games for the club in 1930, earning the nickname “Iron Man.”32

The Lincoln Giants became the Harlem Stars in 1931, then rebranded as the New York Black Yankees in 1932. They remained an independent team, so statistics are limited, but Brown batted .216 in the 29 games those years for which records are available.

After three years in New York, Brown returned to the Chicago American Giants in the second iteration of the NNL from 1933 to 1935. The original circuit had succumbed to the Great Depression. Brown was elected the starting catcher for the West squad in the inaugural East-West All-Star Game in fan voting that summer. (Biz Mackey started for the East after collecting more votes than Gibson.)33 Brown drilled a triple over East center fielder Cool Papa Bell’s head in the bottom of the fifth, but he was tagged out when he overran the base.34 “Brown went on around and came into third and was prepared to stay there. He seemed to be out of run. But the coach stirred him up with a whack and sent him in, and he was out from here to the Cuban revolution,” described the Pittsburgh Courier. 35 The West prevailed, 11-7, to the delight of the 19,568 in attendance at Comiskey Park despite a pregame drizzle.36

Brown started another East-West All-Star game in 1934. That offseason, he teamed with Bell, future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige, and others on a [Tom] Wilson’s Elite Giants squad that dominated the California Winter League with a 34-5-1 record.37 Late in the campaign, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that Brown had caught every contest and allowed only four stolen bases.38 When CAG manager Dave Malarcher resigned in February 1935, Brown was hired to succeed him and led the club to a 27-35-2 record.39 In 102 regular season games for Chicago from 1933 to 1935, Brown batted .302 with three homers and 54 RBIs.

While Chicago dropped out of the NNL and played as an independent in 1936, Brown remained in the circuit, joining the Philadelphia Stars to fill the void left by the departure of Biz Mackey. Stars owner Eddie Gottlieb saw Negro League baseball solely as a business enterprise and booked his team to face numerous other Black squads along the east coast.40 During his first season with Philadelphia, Brown batted .266 in 41 games but slipped to .161 in 26 contests in 1937.

The Stars acquired Bill Perkins to become their regular backstop in 1938. In late May, Brown was released to the Memphis Red Sox – by then a Negro American League franchise – where it was hoped the warmer weather would help him recover from a sore arm.41 To welcome back a popular player, Martin Stadium hosted a Larry Brown Homecoming Day, with extra seating “to take care of the expected overflow crowd.”42 As it happened, the ballpark welcomed its largest attendance in over a decade. Brown was presented with a wristwatch and money. Including last-minute contributions collected by 11-year-old Larry Jr. following a ninth-inning PA announcement. Later that week, journalist Sam R. Brown reported in all caps that the catcher “WAS DEEPLY TOUCHED BY THEIR EXPRESSION AND WITH THE GOOD WILL WITH WHICH HE FEELS THAT HE IS HELD. HE FURTHER STATES THAT HE WILL EVER HAVE A WARM SPOT IN HIS HEART FOR THE MEMPHIS FANS AND BASEBALL PUBLIC.”43

The Red Sox featured a staunch lineup led by Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, who had brought the bulk of his 1937 Cincinnati Tigers team to town following that franchise’s collapse. Brown’s presence allowed Double Duty to focus more on pitching and managing. After Radcliffe caught Satchel Paige in the first game of a 1932 doubleheader at Yankee Stadium for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and pitched the second, New York American sportswriter Damon Runyan wrote “it’s worth the admission price of two to see ‘Double Duty’ Radcliffe in action.44

Brown led Memphis to three straight wins over the Birmingham Black Barons.45 The Red Sox claimed the first-half pennant with a 21-4 record and met the Atlanta Black Crackers, the second-half winners, in the NAL championship series. Memphis won the first two games at home; however, when the Black Crackers arrived late for Game Three in Birmingham, Alabama, NAL president R.R. Jackson called the game off. Ponce de Leon Park, home of the Southern Association’s all-white Atlanta Crackers, would not be available until the weekend, so the Black Crackers requested a delay. The Martins refused because of the “heavy expense” of keeping their team in Atlanta.46 At an impasse, the series never resumed. Finally, in December, the NAL officially declared the Red Sox the circuit’s 1938 pennant winners.47

Memphis rejuvenated Brown. In the late 1930s, he was selected for four straight East-West All-Star teams – 1938, 1939 (two games), 1940, and 1941 – for a total of six teams and seven games in his career.48 In 1941, he also played 29 games for the Alijadores de Tampico in the Mexican League. Then, from 1942 to 1948, Brown managed the Red Sox for five of seven seasons. After that, he continued to play sporadically, taking his final at-bat for Memphis in 1947 when he was 45.

One of Brown’s most significant achievements as a player was the success of his protégé Verdell Mathis, a hard-throwing lefthander from Memphis’ Booker T. Washington High School. Mathis joined the Red Sox from the semipro ranks in 1940. After catching him in a bullpen session, Brown told Red Sox manager Ruben Jones, “This guy is ready now.”49 Under Brown’s tutelage, Mathis developed into one of the best pitchers in the Negro Leagues. While they were roommates, Brown sat on the side of the bed each morning, going over every hitter they would face that night, telling Mathis, “Look, you can become a star, but you’ve gotta do what I tell you.”

Facing Josh Gibson, for example, Brown shouted to Mathis, “Heh, Lefty, be careful with this guy. He’s been hitting the ball out of all these parks.” After Gibson fouled off two balls lobbed over the plate, Brown called time, visited Mathis on the mound, and told him, “Don’t try to trick him this time, just throw the ball through the middle of the plate.” Back behind the plate, Brown told Gibson what was coming, but the slugger missed and struck out. Brown’s keen understanding of the mental side of the game allowed Mathis to grow as a pitcher. Brown believed that Mathis could outperform the game’s most renowned pitching star, Satchel Paige. Mathis defeated Paige three times in head-to-head meetings, including a 1-0 pitcher’s duel at Wrigley Field in front of 30,000 fans.50 When Mathis shined on the biggest stage, so too did Brown.

“[Roy] Campanella and Josh were better hitters, but Larry was a better receiver than either one… I never saw the guy miss a pop fly,” said Mathis. “The only mistakes I made was when I shook off his signals.”51

By 1947, with the eyes of Black America focused on Jackie Robinson’s historic breakthrough, the Martins invested $250,000 to modernize Martin Stadium, including a players’ lounge, refurbished concession stands, and an apartment section where single players could live during the season.52 As the Red Sox’s manager that season, Brown understood the pressure on his club to perform and convinced the Martins to sign Cuban stars Pedro Formental and José Colás to fortify the lineup. Colás earned a spot in each of the two 1947 East-West All-Star games as an outfielder. In the first game on July 27 at Comiskey Park, he hit two singles to help the West to a 5-2 victory.53 Later that summer, Brown watched as Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey descended upon Memphis to land Red Sox pitcher Dan Bankhead, the first Black man to pitch in the National League (Satchel Paige followed suit for the American League in 1948). Bankhead’s signing generated great excitement to Memphis’ Black fans when it was announced over the loudspeaker at Martin Stadium and reported by the Memphis World.54

Too old to enjoy the fruits of integration himself, past his prime and unable to play winter ball, Brown spent his offseasons in Memphis working as a waiter at local hotels, including the Hotel Gayoso on Main Street and the William Len Hotel on the corner of Main and Monroe.55 It allowed him to stay connected with the community and keep his face in the crowd.56

Brown’s oldest son, Larry Jr., was a member of the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II and served through the Korean War.57 In 2007, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush.58 Brown remarried in October 1958 to Sarah Belle Woods; together they had one son, Wendell Brown, who served 33 years in the USMC, where he attained the rank of Sergeant Major.59

Brown Sr. retired from the William Len Hotel in 1970. When former Memphis Red Sox owner Dr. J.B. Martin looked back in 1955 on catchers who had played in the Negro Leagues, he opined that three-time National League MVP Roy Campanella had to be considered the best based on his accomplishments in the majors. “After Campy, I guess I’d take Gibson and then Larry Brown,” Martin said.60

The nine-member committee that elected former Negro League standouts Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard to the National Baseball Hall of Fame did consider Brown’s candidacy.

Brown died on April 7, 1972, three months before Gibson’s induction into Cooperstown.61 He is buried at New Park Cemetery in Memphis.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Delores Brown, Larry Brown’s daughter-in-law, for her assistance with this biography, which was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Tim Herlich. Thanks also to Paul Proia for his input during the first stage of review.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com and www.seamheads.com.

Notes

1 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Pub., Inc., 1994): 122.

2 Larry Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File, accessed June 2022.

3 Gary Ashwill, “Fielding,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, accessed June 28, 2022.

4 Kyle McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching and Catching in Baseball’s Negro Leagues, (Minneapolis: McNary Publishing, 1994): 240-241.

5 Pittsburgh Courier, June 26, 1930.

6 Larry Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File, accessed June 2022. Brown’s daughter-in-law, Delores Brown, possesses a copy of Larry Brown’s birth certificate and confirmed that September 5, 1905, is correct to the author.

7 Byron Motley, “Brown, Larry,” Oxford American Studies Center, https://oxfordaasc.com/browse;jsessionid=F477BC46E32B935C909BEB13066B1FA2?pageSize=20&sort=titlesort&t=AASC_Eras%3A5&t_1=AASC_Occupations%3A1169&type_0=primarytext&type_1=subjectreference (last accessed July 10, 2022) and Delores Brown, interview by author, August 10, 2021.

8 Two Industrial Towns: Pratt City and Thomas (Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Historical Society, 1988): 3.

9 John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (Westport: Meckler Books, 1989): 43.

10 Larry Brown, interview by John Holway, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File, 1970, accessed June 2022.

11 Brown, interview by John Holway.

12 Gary Ashwill, “Larry Brown” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, accessed June 28, 2022, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=brown01lar

13 Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File.

14 Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File.

15 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues: 236-238.

16 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: DeCapo Press, 1992): 208-209.

17 Larry Brown Jr., video interview by Steven Ross, April 1994. Video #85. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

18 Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1961.

19 “Brown May Rest in Hall of Fame,” Tri-State Defender (Memphis, Tennessee), April 22, 1972: 9.

20 Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File.

21 Gary Ashwill, “1927-28 Cuban League,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, accessed June 29, 2022, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1927.5&teamID=CUB&LGOrd=1

22 Brown, National Baseball Hall of Fame Biographical Clippings File.

23 Delores Brown, interview by author, June 22, 2022.

24 “World Series Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, October 8, 1927: 9.

25 “Last,” Chicago Defender, October 22, 1927: 9., “Chicagoans Become Colored Champions,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1927: 22.

26 Gary Ashwill, “1927 Chicago American Giants,” Seamheads Database, accessed June 28, 2022, and Riley, 122.

27 Keith Wood, “The Harassment of Dr. J.B. Martin: A Story of Southern Paternalism in 1940 Memphis,” Black Ball Journal vol. 8 (2016), 75.

28 Gary Ashwill, “1929 New York Lincoln Giants,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, accessed June 29, 2022, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1930&teamID=NLG&LGOrd=3

29 “Giants Drop Championship,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 4, 1930: 15.

30 Dick Clark and John Holway, “1930 Negro National League,” History Studies International Journal of History 10, no. 7 (2018): http://research.sabr.org/journals/1930-negro-national-league

31 Rob Neyer, “Did Gibson Hit One Out of Yankee Stadium,” ESPN, May 19, 2008, accessed June 13, 2019, https://www.espn.com/mlb/columns/story?columnist=neyer_rob&id=3403111

32 https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/brownl.html

33 “The East-West Game Player Vote,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 9, 1933: A5.

34 Frank A. Young, “First East vs. West Game, Chicago, IL,” Kansas City Call, September 14, 1933.

35 “West Triumphs Over East in 11-7 Thriller,” Pittsburg Courier, September 16, 1933.

36 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 401.

37 http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/California%20Winter%20League%20Standings%20(1910%20-%201947).pdf

38 “Larry Brown Big Aid to Winter League Club,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 2, 1935: A5.

39 Insider, “Giants to Rebuild Ball Club,” Chicago Defender, February 9, 1935: 17.

40 Stan Hochman, “Five Surviving Philly Stars, Negro Leagues to Be Honored Finally,” Philadelphia Daily News, May 27, 2008.

41 “Brown to Memphis,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 28, 1938: 16.

42 Sam R. Brown, “Birmingham at Memphis for 4 Games,” Chicago Defender, June 4, 1938: 9.

43 Sam R. Brown, “Red Sox Have Won Eight While Losing Only Four,” Atlanta Daily World, June 10, 1938: 5.

44 Kyle McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe (Minneapolis: McNary Publishing, 1994): 71.

45 Commercial Appeal, June 6, 7, 8, 9, 1938.

46 Birmingham News, October 1, 1938.

47 “Memphis Gets 1938 American League Pennant,” Chicago Defender, December 17, 1938: 9.

48 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-1962, Expanded Edition (Kansas City, Noir Tech Research, 2020), 420.

49 Verdell Mathis, video interview by Steven Ross, April 1994. Video Verdell Mathis #2. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

50 Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It: 147-149.

51 “Brown May Rest in Hall of Fame,” Tri-State Defender (Memphis, Tennessee), April 22, 1972: 9.

52 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players & All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford Press, 1970), 197.

53 Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues: 184.

54 Memphis World, August 26, 1947 & William O. Little, video interview by Steve Ross. April 1994. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

55 Memphis City Directory (Memphis: R. L. Polk &, 1941), 136 & Memphis City Directory (Memphis: R. L. Polk &, 1951), 131.

56 Larry Brown Jr., video interview by Steven Ross, April 1994. Video #86. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

57 Delores Brown, interview by author.

58 Kirk, Bryan. “Larry Brown, Legendary Tuskegee Airman, Speaks to High School Students.” Patch, November 18, 2016.https://patch.com/texas/houston/larry-brown-legendary-tuskegee-airman-speaks-high-school-students?fbclid=IwAR1hj2NicrJlwlmrIlHcJU-m-bXdjFng7xIMOJ6mYAEyswzlYSuzp8HICbw

59 Delores Brown, interview by author, August 21, 2022.

60 Sam Lacy, “Campy’s a Great Catcher But Say Oldtimers ‘You Ain’t Seen Nothing,” Afro-American (Baltimore, Maryland), August 27, 1955: 15.

61 New York Times, April 10, 1972.

Full Name

Ernest Larry Brown

Born

September 16, 1901 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

April 7, 1972 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.