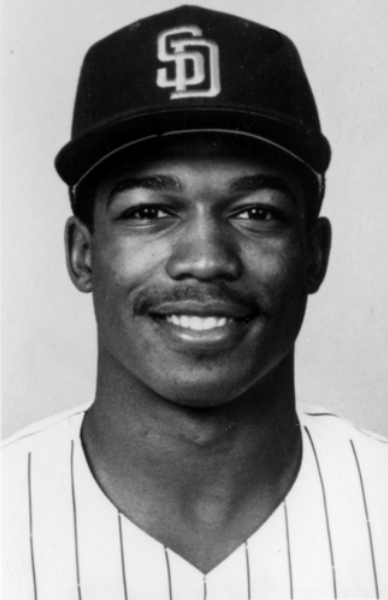

Stan Jefferson

It was a dream come true for 23-year-old Stan Jefferson when he led off against San Diego lefty Dave LaPoint in the first game of a doubleheader at Shea Stadium on Sunday, September 7, 1986. He grew up in the Bronx, had been the Mets’ first-round choice in the 1983 amateur draft, and had just been called up from Tidewater, the Mets’ Triple-A International League farm team. Jefferson struck out in his first major-league appearance, but he reached base and scored after he was hit by a pitch in the bottom of the second, and got his first big-league hit when he singled to left in the fourth.

It was a dream come true for 23-year-old Stan Jefferson when he led off against San Diego lefty Dave LaPoint in the first game of a doubleheader at Shea Stadium on Sunday, September 7, 1986. He grew up in the Bronx, had been the Mets’ first-round choice in the 1983 amateur draft, and had just been called up from Tidewater, the Mets’ Triple-A International League farm team. Jefferson struck out in his first major-league appearance, but he reached base and scored after he was hit by a pitch in the bottom of the second, and got his first big-league hit when he singled to left in the fourth.

Jefferson was the focus of more media attention than your usual September call-up. Some of the attention came from his status as a highly touted draft choice, but at least as much came from the fact that he was a native of New York City. When rowdy elements of the 47,823 fans in attendance stormed onto the field after the Mets clinched the NL East pennant on September 17 and tore up the field in a riot reminiscent of those in 1969 and 1973, scribes naturally interviewed general manager Frank Cashen. When they turned their attention to players, though, many approached Jefferson first, not one of the team’s stars—even though the pennant-clinching game was only his fifth in the majors, and he had entered the game as a pinch-runner in the seventh inning. He was too young to remember the 1969 riots, but said he remembered 1973. “That was the way to show your emotions,” Jefferson said. “In the past, that’s what you did, but it’s not cute anymore.”1 He started in center field the next three nights and got firsthand experience navigating in the patched-up outfield turf.

When Jefferson stepped to the plate in the bottom of the sixth against the Phillies on September 20, he was only 2-for-16 for the month. He later admitted that he had been suffering under the desire to perform well for his family and hometown friends. “I put the pressure on myself,” he said, “because I know my ability and I wanted to do well in front of my folks. I mean, I was playing against Mike Schmidt.”2

With Danny Heep on second base and two outs, Phillies reliever Tom Hume intentionally walked Mets leadoff hitter Mookie Wilson. Jefferson looked toward manager Davey Johnson in the dugout, expecting to be removed for a pinch-hitter. “He looked back at me,” Johnson recalled, “but I just gave him a wink and said, ‘Let’s go.’ It gave him confidence.”3 Jefferson responded with a three-run homer, and was pushed from the dugout to doff his cap for the 39,000-plus fans still celebrating the team’s clinching of the NL East pennant the previous week.

Jefferson finished with a .208 batting average (5-for-24) in 14 games, five of them as a starter. Not great, but a promising start to what appeared to be a long major-league career.

Stan Jefferson was born on December 4, 1962, in New York City. His father, Everod, a subway conductor and immigrant from Panama, later moved his family from a tough South Bronx neighborhood to the quieter Co-op City cooperative housing development in the Baychester section of northeast Bronx. The huge development, claimed to be the largest single residential development in the United States, was completed in 1973, and has more than 15,000 residential units in 35 high-rise buildings and seven townhouse sites. “Co-op was a great place to grow up,” Jefferson recalled in a 2015 interview. “Co-op was very sports-conscious and very supportive. There was no shortage of people to play with. We had teams for every sport and lots of room and places to play. I played all day long — baseball, basketball, football on the greenway, stickball against a wall, everything.”4

Jefferson graduated from Little League—coached by his father—to the Bronx Federation League, where he developed his skills and earned a reputation as one of the best and fastest sandlot players in the city. But he did not go out for baseball at Harry S. Truman High School until he was a junior. “I was just a little guy, maybe 5-foot-6 and about 130 pounds,” he said. “It would have been uncool to be cut from the team, and I didn’t want to take that chance.”5 (He later grew to a well-muscled 5-foot-11 and 175 pounds.) He also wrestled at Truman, and ran track one year. He loved football, but the school did not have a team until his senior year.

Jefferson’s baseball exploits attracted the attention of Earl Battey, the four-time All-Star catcher with the Minnesota Twins in the 1960s. Battey was also a resident of Co-op City and since 1968 had been running the Con Ed Answer Man community relations program for Consolidated Edison of New York. The company purchased bleacher seats from the Yankees and gave them free to inner-city kids. Battey chaperoned the kids at the games and answered baseball questions. He also conducted clinics that included advice on school and general behavior in addition to teaching baseball. Jefferson was a volunteer mentor two summers for the program while in high school.

In 1980 Battey decided to attend Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach to earn his college degree. Battey had accepted an offer to become an assistant baseball coach there, and recruited Jefferson to play for head coach Don Dungee’s team. Jefferson was also attracted by the strong academic reputation of the historically black college. He was a standout performer at Bethune. In 1983, his junior year, he attracted major-league scouts by hitting .408 in 52 games, with a .591 slugging average and a .512 on-base percentage.6 His 67 stolen bases—in 68 attempts!—led the NCAA.

Willie Daniels, a friend from Co-op City who played with Jefferson in Little League, at Truman High, and at Bethune, claimed Jefferson was caught that one time only because his spikes slipped on a wet track. “I played with Devon White, Shawon Dunston, Walt Weiss, a lot of guys,” said Daniels in an interview years later. “Stanley is one of the best pure athletes I’ve ever seen.”7

Coaches Dungee and Battey told Jefferson that a couple of major-league scouts had been asking about him, and wanted to know if he would sign a contract if picked early in the June 1983 free-agent draft. Jefferson had not actually thought about entering the draft early until then. He had seen a couple of scouts in the stands, but had not talked to any of them. “At Bethune our field was at the Rec Center in a black neighborhood in Daytona,” he said. “The only white people at our games were scouts or families from the other teams. One day I saw a very tall, gangly white guy standing behind me in center field, carrying a small baby. Eventually he went to the bleachers. I saw him a couple more times during the season, but didn’t know who he was.”8 (Later he learned that the gangly scout was Joe McIlvaine, the Mets scouting director.)

Jefferson gave it some thought and decided to sign if drafted in the first two rounds. “It was a no-brainer, actually,” he said. “I didn’t see my stock go any higher by staying [in college] one more year.”9 Dungee and Battey were supportive.

The Mets drafted Jefferson in the first round, 20th overall, and in July he was voted to The Sporting News College All-American Team. His professional career got off to a great start at the Mets’ short-season Single-A Little Falls team in the New York-Pennsylvania League. He hit .320, compiled a .402 OBP, led the league with 35 steals, and was voted to the league’s all-star team. The Mets had the right-handed Jefferson convert to switch-hitting in 1984, figuring he could take advantage of his speed from the left side to leg out more infield hits. (Some news stories claimed he began switch-hitting in 1983, and baseball-reference.com lists him as a switch-hitter in 1983, but Jefferson said he hit right-handed at Little Falls.) He had a solid year in 1984 with the Mets’ Lynchburg team in the Single-A Carolina League, hitting .288 in his first year as a switch-hitter, leading the league with 113 runs scored, and stealing 45 bases. He was also selected to the league’s all-star team.

The Mets were optimistic about 1985 and the team’s future. They had gone from 68-94 and last place in the six-team NL East in 1983 to 90-72 and second place in 1984. Their farm system was stacked —the overall winning percentage was .574 (400-297), and three of their six teams were pennant winners. General manager Frank Cashen was enthusiastic as he ran down the list of up-and-coming minor-league outfielders during spring training. “In A-ball,” he said, “we have Stanley Jefferson, who may have the most potential of all.”10

Jefferson struggled a bit at the plate in 1985 at Jackson of the Double-A Texas League. He hit .277, led the league with 39 steals, and finished third in runs scored with 97. The Mets sent him to the Florida Instructional League after the season, and were impressed with his continuing progress as a left-handed hitter in his second year as a switch-hitter. Mets beat writer Jack Lang wrote, “He suffered a letdown from the left side in midseason, but made a late recovery and continued to improve in Florida.”11 The team placed Jefferson on its 40-man roster in November, protecting him from the December Rule 5 draft.

Jefferson married Carmelita Jenkins on November 5, 1985. They had met when he was playing in Lynchburg. He was settling down, the future looked bright, and he could not wait to report to the Mets’ 1986 spring-training camp. Jefferson turned heads with his early performances in camp. Veteran slugger George Foster was among many who were impressed. “You don’t find too many batters who can drive the ball from both sides as well as Stanley can,” said Foster. “He’s going to win a batting crown.”12

Unfortunately for Jefferson, the Mets were favored to win the NL East and likely to go for it with experience. They seemed set in the outfield with veteran Foster (37 years old), Mookie Wilson (30), and youngsters Darryl Strawberry (24) and Len Dykstra (23). Utilityman Kevin Mitchell (24) could fill in for the fifth outfield spot. Despite the fact that Mookie Wilson was going to start the season on the disabled list, and despite hitting .500 (13-for-26) in 11 “A” games, with two doubles, a triple, and a home run, Jefferson was optioned to Tidewater on March 26. He took it philosophically. “They want me to play every day,” he said, “so I’ll go down and do what I can. They said if they need help they’ll give me a ring.”13

Jefferson hit .290 at Tidewater in 1986, but was sidelined for several weeks because of injuries and played in only 95 games. He led the team with 25 stolen bases, which managed to rank fourth in the league. In hindsight, the injuries probably foreshadowed the physical problems he would contend with the rest of his career. He had also been briefly sidelined in spring training by a slight Achilles tendon strain in his right foot and a back strain.

As a September call-up Jefferson was not eligible for the postseason roster, and was not around to watch the Mets win the NL playoffs and the World Series. Instead, the Mets sent him off to get more experience by playing for Mayaguez in the Puerto Rico Winter League. He was surprised, but not that disappointed, when the Mets announced a December 11 eight-player trade with San Diego—Jefferson was traded to the Padres, along with Kevin Mitchell, Shawn Abner (the Mets’ number one draft choice in 1984), Kevin Armstrong, and Kevin Brown in exchange for Kevin McReynolds, Gene Walter, and Adam Ging. McReynolds was the key for the Mets. They felt they needed more right-handed power in the outfield to complement their young left-handed-hitting right fielder, Darryl Strawberry—the Mets already had two speedy singles-hitting outfielders, Lenny Dykstra and Mookie Wilson. Realistically, Jefferson was expendable.

Even though he had just 14 games of experience in the majors, San Diego was counting on Jefferson to lead off and play center field. Larry Bowa, the new Padres manager, traveled to Puerto Rico to watch a couple of his young players and came back impressed with Jefferson. So were his new teammates, especially with his speed and outfield range. “Put it this way: fly ball to center with two outs in the ninth?” said Amos Otis, a former Gold Glove outfielder with Kansas City and now a Padres outfield coach. “Start the car ’cause he’s got it. Pop fly to short center? Send the kids for hot dogs because he’s got it.”14

On March 30 Jefferson suffered an injury that threatened to derail his season. The Padres were playing the California Angels in Palm Springs, in the last exhibition series before starting the season in San Francisco. Jefferson was looking forward to playing against his old pal, Devon White, now a rookie outfielder for the Angels. Their families were friends, and Jefferson’s father had often picked up Devon on weekends when the two youngsters played against each other back in the Bronx Federation. Jefferson’s father had traveled to Palm Springs for the series, and got together with Stan and Devon on the night before the March 30 game.

Jefferson led off with a hit to left center off Don Sutton. “I knew Devon was going to get to the ball,” he recalled years later. “My mentality was that if Devon was a little lazy or nonchalant getting to the ball I was going to go for second base. What happened was that the ground was a little wet and I slipped and twisted my left ankle really bad. One of those basketball-type ankle injuries. I was down on the ground and couldn’t move.”15

Manager Bowa did not think the injury was as serious as Jefferson did, and was angry when Jefferson said he couldn’t play on Opening Day, April 6. Jefferson consented to play on April 7 to stop the bickering. “I couldn’t stop, turn, or anything,” he claimed in a 2015 interview. “My ankle, from then on has never been the same.”16 He played five games, but was placed on the disabled list and missed 23 games.

The Padres were having a miserable time. On May 7, when Jefferson was reactivated, the team’s 7-23 record was the worst in the majors, and the volatile Bowa had reacted with several clubhouse tirades. On April 26 in Los Angeles “he took the team behind closed doors for a ‘discussion’ that one player rated a 9.5 on a 10 scale. Bowa not only kicked, threw, and screamed, but pointed out specific players who he felt weren’t pulling their weight.”17

Players coped in different ways. When Tony Gwynn, the team’s best player, was asked how life was in the clubhouse, he said, “I don’t know. I just stand in the clubhouse, back into my locker stall and watch the manager scream.”18

Future Hall of Fame reliever Goose Gossage was happy to be traded to the Cubs in 1988. “Every day with him is a crisis,” Gossage said. “The man’s insecure. It’s like getting out of prison, getting away from Bowa.”19

Jefferson was the victim of another Bowa clubhouse tirade during a series in Pittsburgh on May 12-14, just a few games after he came off the DL. The manager did not know what to think about his rookie center fielder, who was hampered by a sore wrist and a sore shoulder as well as the ankle. Bowa still thought he was not trying hard enough to play through his injuries, and could not figure out the player’s personality. In spring training Bowa and the other coaches had been on Jefferson because of his perceived lackadaisical attitude. They did not understand that it was just Jefferson’s New York City streetwise “cool,” not a lack of effort. He had always had a heads-down, laid-back attitude. “I’m always looking down, I guess,” Jefferson said. “I’ve always had this relaxed attitude, and people get the wrong impression. I do the same thing, whether I’m going good or bad.”20

Pittsburgh swept the series, and Bowa was yelling and screaming in the clubhouse after the 9-5 loss on May 13. He dialed it up a notch when he came upon Jefferson sitting in front of his locker, staring at the floor. “I didn’t even notice that Bowa was having a fit,” Jefferson remembered. “I was just shaking my head back and forth, lost in my own thoughts, not believing we’d lost another one. Then I heard Bowa shout, ‘What the [bleep] are you smiling about, Jefferson?’ I tried to ignore him, but he kept shouting at me. Then I lost my cool and shouted back at him, ‘What is wrong with you? Every day you are yelling at me.’”21

Bowa grabbed Jefferson by the collar, and Jefferson shoved back. It took several players to separate the two. “Jefferson was carried out of the locker room, kicking and screaming, by five of his teammates,” wrote the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Barry Bloom.22 Years later Jefferson realized it was a youthful error, and figured he should have just sat there and taken his punishment.

Bowa apologized a little later, claiming he had been fired up about Jefferson skipping an extra batting-practice session, but learned that no one had told Jefferson about it. He kept Jefferson in the lineup despite the dustup. Jefferson played in the next 14 games, starting all but one, but continued to have problems with shoulder tendinitis in his throwing arm, and was placed on the 15-day DL after the May 29 game in San Diego. When he came back he went into a slump, dropping his batting average from .250 when he went on the DL to .216 on July 11. For the next month he went on a 34-for-95 hitting spree, bringing his average up to .267. That corresponded with a modest surge by the team, and it appeared that Jefferson was starting to live up to expectations that he would be a leadoff hitter who could ignite the offense. The Padres, 30-58 at the All-Star break, had a 15-10 record during Jefferson’s spree, and 35-39 for the second half.

But from August 10 to the end of the season Jefferson hit only .169 (27-for-160), and finished with a .230 batting average. He could not wait to get back home with his wife Carmelita and two daughters, 2-year-old Tiffany and newborn Brittany. “I was in a sour state toward the end of last year,” he said. “I wasn’t happy with the way I was playing or how I was feeling physically. I was just glad when the season was over.”23

After a short time at home Jefferson decided to put the last season behind him and started spending long hours in the batting cage. He reported early to spring training in Yuma, Arizona, with a positive attitude. Teammates and coaches immediately noticed the changes. He seemed to be having fun again, and it showed on the field. He was more patient at the plate and hitting well over .300 in exhibition games.

The Padres got off to a slow start again in 1988, and so did Jefferson—he went hitless in his first 16 at-bats. Manager Bowa stuck with him as his everyday center fielder for a while, but eventually lost patience. Jefferson, hitting just .105 (4-for-38), was sent down to Las Vegas in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League on April 20. He responded well to the demotion, hitting .317 in 74 games with the Stars, with some power—24 of his 88 hits were for extra bases and his .453 slugging average was a career best. And even better, his .396 on-base percentage was what the parent team was looking for in their presumed leadoff hitter.

The Padres called Jefferson back up in late July. While he was gone, Larry Bowa had been fired and general manager Jack McKeon stepped in to manage. The team, 16-30 under Bowa, responded well to their new manager, and were 67-48 for the rest of the season. Jefferson went hitless in his first game back on July 29 but then went on a seven-game hitting streak. After the streak ended he went into another slump and was relegated to spot duty by mid-August. He had only four hits in his last 44 at bats, finishing the season with a .144 batting average, 16-for-111 in 49 games. San Diego batting coach Amos Otis placed the blame for Jefferson’s hitting woes on his refusal to listen to his coaches. “I can understand wanting to do something your way,” Otis said. “But when your way doesn’t work, you’ve got to change.”24

Jefferson claimed the problem was all the conflicting advice the team was giving him. “I was left alone [in Las Vegas] and found my hitting stroke all by myself,” he said. “But I wasn’t back in San Diego three hours before I was getting advice. Everyone is telling me what to do and how to do it. I didn’t get this much advice in elementary school.”25

The Padres also were not pleased that Jefferson refused to play winter ball. He said he had already done that once, in Puerto Rico, and did not see how that helped him. “The thing is,” he argued, “I’ve done it everywhere, at every level, except here. The only way I am going to improve here is to do it here.”26

On October 24 San Diego traded Jefferson, along with pitchers Jimmy Jones and Lance McCullers, to the New York Yankees in exchange for slugger Jack Clark and pitcher Pat Clements. New Yankees manager Dallas Green said Jefferson would compete with Roberto Kelly and Bob Brower for the starting center field job.

Kelly won the starting job in spring training, and Jefferson was optioned to Triple-A Columbus on April 16 after starting only one of the Yankees’ first 10 games. He was called up again on April 26 when outfielder Mel Hall was placed on the disabled list. Three days later Jefferson blew up in Green’s office when the manager told him he was being sent down to Columbus again. “I busted my [bleep] every day and all you do is ridicule me,” Jefferson shouted as he stormed out of Green’s office. “Every [bleeping] day. I gave you 150 percent. The only guy that was in my corner was Hondo (hitting instructor Frank Howard).”27 Green stepped out of his office and shouted back, “Look in the [bleeping] mirror, big boy.”28 Pitching coach Billy Connors stepped in front of Jefferson to prevent a physical altercation.

The Yankees traded Jefferson to Baltimore on July 20 for Triple-A pitcher John Habyan. Jefferson was called up by the Orioles on August 8 after playing at Rochester for two weeks. At that time, Baltimore had led the AL East all year, but had a 10-16 record since the All-Star break, and were fighting to hold off the Toronto Blue Jays. Jefferson got off to a slow start at the plate, but got hot down the stretch, hitting .319 (23-for-72) in his last 21 games. For the season at Baltimore, he batted .260 in 35 games.

Jefferson started the season with Baltimore in 1990, but did not figure in the Orioles’ long-term plans. He was hitless in 19 at bats in the team’s first 19 games, and then was released. Cleveland claimed him off waivers on May 7. The Indians played Jefferson in about half of their next 66 games (27-for-66) and then sent him down to Triple-A Colorado Springs. He hit .345 in 33 games for the Sky Sox, and was called back up by the Indians in September. He put on a good show for them. He hit .317 (20-for-63) while playing in 22 of the team’s final 27 games.

Despite his September surge, Jefferson did not think he got a fair shot with Cleveland in spring training, believing the team was concerned about his physical condition. “I was never really healthy,” he admitted. “They probably saw me in the training room a lot, trying to get myself together.”29 He started the season back in Colorado Springs, and although he had hit a respectable .284 in 28 games, was released by Cleveland on July 5. Cincinnati signed him as a free agent on July 18, and assigned him to Triple-A Nashville. The Reds called him up on August 30, but he sat on the bench. He played in 13 of the team’s remaining 35 games (only three as a starter) and hit 1-for-19.

The Reds granted Jefferson free agency on October 15. He went to play winter ball with Ponce in Puerto Rico at the suggestion of Cincinnati manager Lou Piniella, who told him to get some at-bats and come to spring training to battle for a job. Two other young Cincinnati outfielders, Chris Jones and Reggie Sanders, would be playing with San Juan.

In just his third game for Ponce, Jefferson fell awkwardly on a muddy field while chasing down a fly ball in center field, and ruptured his left Achilles tendon. It was effectively the end of his career, at age 28. The ankle and lower Achilles were a mess. Yankees surgeon Stuart Hershon performed surgery to reattach the tendon. Jefferson said the doctor told him that there was little healthy tendon left, and that the surgery might not work well enough for him to return to baseball. Jefferson figured he was running on scar tissue for years after his 1987 injury.

Jefferson was on crutches for months, and went into depression. The Reds refused to pay any of his medical bills because he was not under contract with them, and other bills mounted. He owed $4,000 to Dr. Hershon, and bill collectors were calling constantly. His wife, Carmelita, could not take the stress and left for Virginia with their two daughters. (They eventually were divorced.) Just barely off crutches, Jefferson tried out with Kansas City’s Omaha Triple-A team, but it was too soon after the surgery. He also tried out for the Monterrey Industriales in the Mexican League in 1994, but his ankle did not hold up. “The ankle just blew up like a balloon after a game,” he said. “That was my last hurrah.”30

The Mets called Jefferson in early 1995, asking if he would go to spring training as a replacement player. (The Players Association had been on strike since August 12, 1994, and the MLB Executive Council voted on January 13, 1995, to use replacement players for spring training and the regular season.) Jefferson told the team he did not think he could play every day. He made a deal to go to camp in return for a job as a coach in the organization. He had not been able to find a regular 9-to-5 job since 1991, and felt he needed a baseball job to help get out of debt. He was a little uncomfortable about joining the strikebreakers. “If any of those ballplayers out there on strike want to call me, I’ll explain,” said Jefferson. “I’m pulling for the union. I want those guys to get everything they are asking for. But this is about life.”31

Jefferson was released on March 30, but the Mets gave him a job as bench/outfield coach with short-season Single-A Pittsfield. That was his last job in baseball. He found a regular job as a warehouse manager for a lighting company, and went back to school at Mercy College to finish his degree. He had dreamed about becoming a detective while growing up, and passed the New York Police Department civil-service exam and interviews in 1994. He was accepted into the Police Academy on December 8, 1997, graduated in the spring of 1998, and was assigned to the Midtown South Precinct.

Police work was everything Jefferson hoped it would be. “You got to live your dream twice [baseball and NYPD],” his old friend Willie Daniels told him. “Most people don’t even get to live their dream once.”32

Jefferson was on duty on Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, when he and his partner were directed to proceed to Union Square to help direct and comfort people fleeing from the explosions and collapse of the World Trade Center towers. He saw the second plane crash into the second tower, and worked at the site until 9 P.M. the 11th and worked 12 hours on September 12. Then he worked 12-hour shifts on the “pile” on September 13 and 14, and many other shifts at Ground Zero in the following weeks. By the end of the year he was severely depressed and having coughing spells and nightmares. In the spring of 2002 Jefferson was experiencing panic attacks and had difficulty sleeping. He took 41 sick days in the first few months of 2003 as his panic attacks worsened. In March, days after he underwent angioplasty to correct a coronary artery blockage, his mother died suddenly, and his depression and agoraphobia got worse. He was a regular visitor to the emergency room at Our Lady of Mercy Hospital in Queens.

In July 2004 the New York police commissioner’s office submitted an application to place Jefferson on ordinary disability retirement, and on November 8, 2004, the department Medical Board approved the request, finding that he suffered from a major depressive disorder. On May 5, 2005, Jefferson, now represented by an attorney, applied for accident disability retirement, claiming he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. By definition, an ordinary disability retirement finding means that the individual is mentally or physically incapacitated for the performance of his duties and ought to be retired, while an accident disability finding means that the disability was caused by an injury sustained in the line of duty. There are significant differences in pension benefits—25 percent of base salary for ordinary disability, 75 percent for accident disability.

On October 17, 2006, the New York County Supreme Court ruled in favor of the police commissioner. The court agreed with the police department’s contention that Jefferson’s disability was not caused by his work at Ground Zero, ruling that “There were numerous references in the materials reviewed linking petitioner’s anxiety and panic, as well as the depression that came with them, to the death of his mother and his incipient cardiac disease.”33 On May 20, 2008, the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, denied Jefferson’s appeal of the ruling.

More tough times were to come. Jefferson’s father died in August 2010, and his second wife, Christie, died in December 2010. (They were married in Las Vegas in August 2004.) But in 2011 Jefferson was finally granted an accident disability disorder, thanks to the 2005 World Trade Center Disability Law that established a presumption that certain disabilities were caused by work at Ground Zero unless evidence proved otherwise. In the first few years after the law was enacted, the police Pension Fund was still forcing officers to prove that their disabilities were directly related to work at Ground Zero. However, appeals courts gradually forced the Pension Fund to reverse its logic to conform to the law—that an accident disability was granted unless it was proved that the disability was not caused by work at Ground Zero.

As of December 2015, Jefferson lived in a high rise in Co-op City. He did not go out much. “I’m just trying to stay healthy, trying to fight PTSD,” he said. “I don’t like to be around crowds. I am boxed in, and it’s kind of hard. But I have my good days.”34

Special thanks to Brian Williams at Harry S. Truman High School in the Bronx for helping me find Stanley Jefferson and speaking to him on my behalf. Also thanks to Dan Ryan for finding some of Jefferson’s old statistics at Bethune-Cookman College. And, especially, thanks to Stanley for graciously responding to all my questions in two lengthy telephone interviews.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also consulted:

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997).

Baseball-reference.com.

FindLaw.com.

Hennepin County (Minnesota) Library online sources: Ancestry Library Edition; ProQuest Historical Newspapers, the New York Times; and ProQuest Newsstand.

Law360.com.

NCAA.org, “Division I Baseball Records.”

NYC.gov, “Workers’ Compensation and Pension Benefits.”

Paper of Record, for The Sporting News, accessed via sabr.org.

Retrosheet.org.

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Stanley Jefferson.

Notes

1 George Vecsey, “The Mark of the Fans,” New York Times, September 19, 1986: D17.

2 Michael Martinez, “Met Rookies Get Into the Act,” New York Times, September 21, 1986: S7.

3 Ibid.

4 Stan Jefferson, telephone interviews with author, December 11 and 17, 2015.

5 Jefferson, telephone interview.

6 “Final 1983 Men’s Baseball Statistics Report, Bethune-Cookman,” provided by Dan Ryan, Bethune Cookman Sports Information Staff, December 17, 2015.

7 Wayne Coffey, “Forgotten Hero,” New York Daily News, March 4, 2007: 76.

8 Jefferson, telephone interview.

9 Jefferson, telephone interview.

10 Joseph Durso, “Mets’ Architects Looking for Room at the Top,” New York Times, February 11, 1985: C1.

11 Jack Lang, “Middle Infield of Future Reshuffled,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1985: 51.

12 Steve Wilder, “Foster ‘pupils’ earn high grades,” New York Post, March 13, 1986.

13 Michael Martinez, “Wilson to Go on Disabled List: Met to Miss Opening Trip,” New York Times, March 27, 1986: B15.

14 Tom Friend, “Padres’ New Center Fielder Says He’s Ready for the Big Time: Cool on the Outside but Hot to Play,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1987: S3.

15 Jefferson, telephone interview.

16 Jefferson, telephone interview.

17 “N.L. West,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1987: 26.

18 Peter Pascarelli, “N.L. Beat: Raines Is a Thorn in Owners’ Credibility,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1987: 22.

19 Peter Pascarelli, “N.L. Beat: Will 1988 Be ‘The Year of the Balk’ in N.L.?,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1988: 35.

20 Friend.

21 Jefferson, telephone interview.

22 Barry Bloom, “Jefferson, Padres Get It in Gear,” San Diego Union-Tribune, August 10, 1987.

23 Curt Holbreich, “Losing His New York State of Mind: Stanley Jefferson Is Learning to Leave Last Season, Last Team Behind,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1988.

24 Bill Plaschke, “Jefferson’s Way Just Not Working,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1988: 22.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Steve Serby, “Green, Stanley in Blowup,” New York Post, April 30, 1989.

28 Ibid.

29 Jefferson, telephone interview.

30 Ibid.

31 Jennifer Frey, “Met Camp Attractive to Players in Need,” New York Times, February 18, 1995: 31.

32 Coffey.

33 “Matter of Jefferson v. Kelly,” 2006 NY Slip Op 26417 [14 Misc 3d 191], October 17, 2006, Published by New York State Law Reporting Bureau, courts.state.ny.us/Reporter/3dseries/2006/2006_26417.htm (accessed November 20, 2015).

34 Jefferson, telephone interview.

Full Name

Stanley Jefferson

Born

December 4, 1962 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.