Tom Glover

Lefty Glover was one of the players who followed the Elite Giants when they relocated from Washington to Baltimore in 1938. Though he pitched for the Elites for over seven seasons, until recently Glover’s background and even his real name were clouded in mystery. However, the discovery of his death certificate in 2020 uncovered his real name as Thomas Glover Moss.1

Lefty Glover was one of the players who followed the Elite Giants when they relocated from Washington to Baltimore in 1938. Though he pitched for the Elites for over seven seasons, until recently Glover’s background and even his real name were clouded in mystery. However, the discovery of his death certificate in 2020 uncovered his real name as Thomas Glover Moss.1

The document further reveals that Glover was born on February 11, 1911, in Montgomery County, Alabama. His mother was Luvelia Moss, born in Montgomery, and his father was listed as Willie Glover, birthplace unknown.2 It appears that Lefty used “Moss” for the early part of his life and career. A box score from August 1, 1932, has “Lefty” Moss pitching for the semipro Atlanta Shops team against the Montgomery Grey Sox.3 However, the April 16, 1933, Montgomery Advertiser lists Tom “Lefty” Glover as a pitcher for the Montgomery Grey Sox of the Negro Southern League.4

Glover did fairly well with Montgomery, pitching a three-hitter against the Birmingham Black Barons in July and a four-hitter against the Detroit Stars in August.5 He next surfaces in late May of 1934, when Birmingham played a series of spring-training games with a tall, lanky newcomer on the mound. Called “Walter Glover” by the Birmingham press, this was actually Tom Glover, and he made an impression right out of the gate. Facing the Atlanta Black Crackers, Glover three-hit them and won 8-0.6 The southpaw then threw another shutout against the Cleveland Cubs, followed by a six-hit, 5-2 win over the Kansas City Monarchs.7 By the time the 1934 Negro Southern League season opened, Tom “Lefty” Glover was Birmingham’s best pitcher and was given the honor of being the team’s Opening Day hurler. Facing the Memphis Red Sox in the first game of a doubleheader, Glover relinquished only six hits while striking out seven to win 5-4. Two weeks into the season, Birmingham’s ace disappeared, making a beeline north to join the Cleveland Red Sox of the Negro National League.8

In the spring of 1935, the Pittsburgh Courier reported that Allan Page, owner of the New Orleans Black Pelicans, had gone to great expense to create a good ballclub and that Lefty Glover was their ace.9 Once again, Glover jumped clubs, this time to the Columbus Elite Giants of the Negro National League. However, because the Elites already had a solid rotation, Glover left the team in June of 1936 and rejoined the Montgomery Grey Sox before jumping to the Birmingham Black Barons in July. He returned to the Elites in 1937 when they relocated to Washington and remained with the club when it finally settled down in Baltimore in 1938.10

By the time he rejoined the Elites, they had an above-average pitching staff anchored by Bill Byrd, Pullman Porter, and Schoolboy Griffith. Since the Negro Leagues played a short “official” season of between 40 and 60 games, three top-tier starters were a luxury. The bulk of an average Negro League team’s games were exhibitions against White semipros or other Black teams that did not count in the standings. For those games, Negro League clubs carried a couple of second-tier pitchers, and this is the role Lefty Glover filled on the Elites.

Newspaper stories described him as a speedball pitcher and curveball artist.11 For many of his games, box scores show a pitcher who recorded few strikeouts but many groundouts or fly outs, validating his mastery of a good curveball. The box scores also revealed that he typically ran out of steam around the seventh inning and sometimes had a problem with his control. The Elites apparently recognized Glover’s weakness and often pitched him in the second game of doubleheaders, which at the time were seven-inning affairs.

Because the Elites had Byrd, Porter, and Griffith, Glover’s official Negro National League record is modest; six wins and six losses for 1937-1939. His nonleague and exhibition games were not recorded.

The year 1939 marked a major milestone in Lefty Glover’s career. That summer, the Elites finished the season with a record of 21-23, good enough to be one of the four teams invited to play for the Ruppert Memorial Trophy, a championship tournament played at New York’s Yankee Stadium and named after the Yankees’ recently deceased owner, Jacob Ruppert. The Elites wound up winning the trophy, defeating the Homestead Grays, winners of the regular-season pennant that year. Winning the Ruppert Cup gave the Elites the title of “Champions,” though the Grays believed their winning the pennant gave them rights to the title. Four teams then played a postseason tournament (Elites vs. Eagles, Grays vs. Stars) with Baltimore defeating the Grays 3-1-1 to claim the season title.12

After going 1-2 in seven league games for the “Champion” Elites in 1939, Glover was invited to join an exclusive group of Blackball players in the California Winter League. This loosely organized league had been in existence since the 1920s and typically featured a couple of all-White teams made up of Los Angeles-based major and minor leaguers and one all-Black team. Over the years, the Black team boasted such future Hall of Famers as Satchel Paige, Turkey Stearnes, and Bullet Joe Rogan, along with many of Blackball’s greatest stars. Because the money was good, to be invited to play in the California Winter League meant you were deemed among the best, and in 1939 Lefty Glover made the grade.

That winter the all-Black team was called the “Philadelphia Royal Giants,” and they fielded a good cross-section of stars.13 Besides Glover, the pitching staff included Elites teammate Bill Harvey and New York Black Yankees ace Terris McDuffie. The rest of the club included Jim West at first, Jake Dunn at second, Marlin Carter at short, Hoss Walker at third, Wild Bill Wright, Mule Suttles, and Bill Hoskins in the outfield and Pepper Bassett behind the plate.14 The all-Black entry was the smart pick for winning the short season, with former Brooklyn Dodgers star Babe Herman’s White Kings team expected to come in a close second.15

On November 6, 1939, the White Kings met the Royal Giants in a doubleheader at Hollywood’s Gilmore Field. When it was over, Glover had pitched a no-hitter and gained immortality for himself in Blackball lore. True to form, he recorded just four punchouts, but his curveball allowed only three balls to leave the infield. His control stayed true as he issued just two bases on balls.16 The Royal Giants won the 1939-40 championship with a 10-6 record. Besides his no-hit masterpiece, Glover led the league with a .750 winning percentage and a 3-1 record.17 It’s at this point that Lefty Glover decided to capitalize on his fame and follow the money. In 1940 this meant south of the border.

While baseball had been played in Mexico since the 1840s, the country’s first functioning league did not start up until 1925. By 1940 the league’s leading benefactor was Jorge Pasquel, a rich importer-exporter from Monterrey and a baseball fiend. Pasquel knew that to have a thriving league he needed to import established stars to both attract fans and help native players elevate their game. Inducing the better-paid White players to come to Mexico was not feasible, but Negro League and Cuban-based players, who drew less pay and faced racial discrimination up north, was easier. Glover’s no-hit masterpiece was reported in most sports pages, making him a known commodity and ripe for Mexican League recruitment.

However, if Glover thought Mexico was going to be easier than the California Winter League, he was very wrong. Besides the best Latin players of the day, the 1940 Liga Mexicana was a veritable who’s who of Negro League superstars, including future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Leon Day, Martin Dihigo, Cool Papa Bell, Ray Dandridge, and Willard Brown, plus almost all of Glover’s Royal Giants teammates. Against this star-studded “outsider baseball” congregation, Lefty went 8-13 in 36 games with an ERA over 5.00. He also bounced around throughout the season, playing for La Junta de Nuevo Laredo, Unión Laguna de Torreón, and Gallos de Santa Rosa, teams that finished fifth, sixth, and seventh in the seven-team league. Glover stayed in Mexico the following year, winning four and losing six for the last-place Carta Blanca de Monterrey.

Just when the Liga Mexicana was shaping up to be a haven for Negro Leaguers, World War II stepped in. Ballplayers in Mexico were instructed to return to the States to make themselves easier for their draft boards to reach and persuade to take jobs in a war-related industry. Glover returned to Baltimore and rejoined the Elite Giants.18

Throughout the summer of ’42, the Elites battled the Homestead Grays for first place in the Negro National League II, but eventually came up short. During a crucial point in the season, Baltimore lost catcher Roy Campanella to Mexico and, lacking his bat in the lineup, lost the pennant to the Grays on the last game of the season.19 Glover was the team’s third starter and had gone 5-3 with a 3.38 ERA.

The next year, 1943, both the Elite Giants and Lefty Glover underachieved, with the team falling to a distant fifth place and Glover delivering a disappointing 3-5 record. Off the field, Lefty did find success, getting married in June of that year to a woman named Gertrude.20

Despite threatening to stay out of baseball in 1944 and remain in his steel plant job, Glover stayed with the Elites but managed only a 1-2 record.21 Glover was expected to take a bigger role in the team’s rotation, with the Baltimore Afro-American reporting, “[I]ndications point to Tom Glover as the North Carolina port-sider appears to be the farthest advanced of the Elite flingers in the matter of conditioning.”22

The next season, 1945, turned out to be Lefty Glover’s Negro League swan song. Though he finished the season 4-3, the fans thought enough of Baltimore’s left-hander to vote him onto that year’s East-West All-Star Game. Glover was picked to start the game but was sent to the showers in the second inning after giving up four runs to the West team. He was charged with the loss in the West’s 9-6 win.23

According to the August 11, 1945 Afro-American, Glover gave the Negro National League the big “to-ell-with-you” and rejoined the Carta Blanca de Monterrey, going 5-1 for the remainder of the season.24 He moved farther south in 1946, first playing winter ball in Panama, where he made the Pro League all-star team and pitched against the visiting New York Yankees, then summered in Venezuela with the Pastora club.25

Glover’s jumping of his Elite Giants contract led to the Negro National League officially banishing him for five years.26 He was absent from American baseball circles until this heartbreaking item in the March 13, 1948, edition of the Baltimore Afro-American:

“Glover at Henryton

“Tom Glover, former Baltimore Elite Giants pitcher, is at Henryton Health Sanitarium and anxious to see his old Baltimore friends and fans.”27

Henryton was a segregated tuberculosis sanitarium in Marriottsville, 30 miles outside Baltimore. Though called a hospital, Henryton was basically a place of exile for TB patients rather than a treatment center.28

Inevitably, a few months later, he died, on June 7 at age 35. His obituary appeared in the Afro-American:

“Ex-Baltimore Elite Giants Hurler Dead

“BALTIMORE. Death closed the career of Thomas (Tom) Glover, former southpaw pitching star of the Baltimore Elite Giants, here Monday morning.

“Glover, who joined the Elites in 1935, saw service in the Negro National League and also performed in the leagues of Mexico, Cuba, Panama and South America. He was said to be 36 years of age.

“His most notable achievement was a no-hit, no-run game he pitched against an all-star major and minor league team on the West Coast in 1939.

“Glover is survived by his wife Gertrude. His death occurred at Henryton Sanitarium.”29

Sources

This biography was modified from the author’s original article “Lefty Glover: Requiem for a Southpaw” published in 21: The Illustrated Journal of Outsider Baseball, Volume 2 that can also be accessed online at https://studiogaryc.com/2021/04/04/lefty-glover-requiem-for-a-southpaw/.

Unless noted, Negro League and Mexican League statistics and final standings referenced are from the Seamheads Negro League Database.

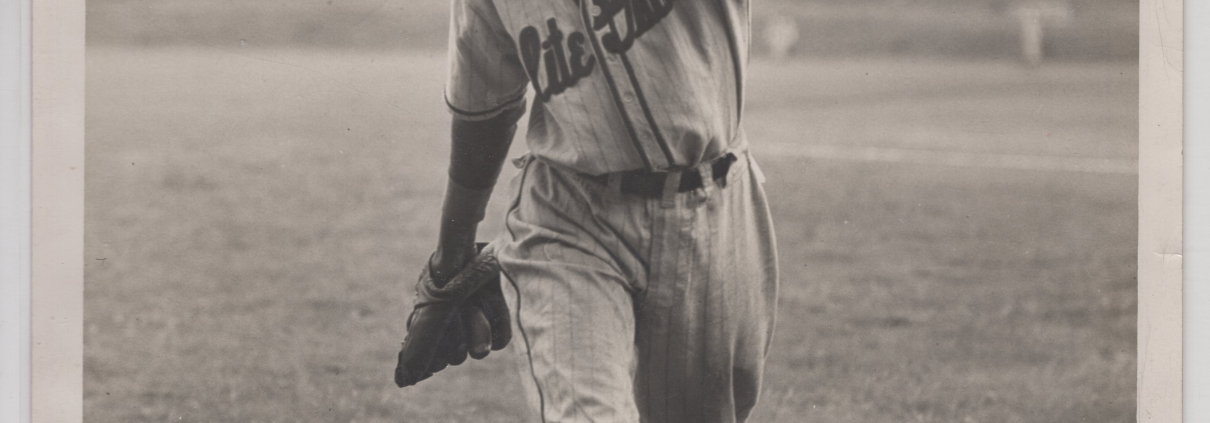

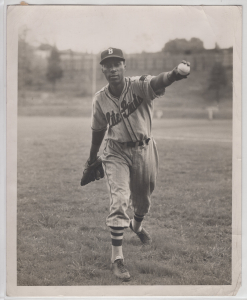

Photo credit: Lefty Glover, courtesy of Gary Cieradkowski.

Notes

1 Glover’s death certificate obtained through the Maryland State Archives.

2 It has been very difficult to learn more details about Glover’s parents. Several families with the surname Moss resided in the Montgomery County, Alabama, region during the 1920 and 1930 censuses, but none appear to have been Thomas Glover’s family. The 1930 census shows a Will Glover with his wife, Flora, 20-year-old daughter, Rosa, and 19-year-old son, Tom residing in Scott, Arkansas. All four are recorded as having been born in Alabama. Will Glover’s occupation is listed as a cotton farmer and Tom Glover as a teamster in the cotton farming industry. Back in the late 1980s, some of his teammates told this author that he had grown up with different relatives, but that is unsubstantiated.

3 “Grey Sox Mill Win, 7-1; 1,200 Fans See Tilt,” Montgomery Advertiser, August 1, 1932: 6.

4 “Grey Sox Mill Battle Nashville Nine Today,” Montgomery Advertiser, April 16, 1933: 6.

5 “Glover Hurls Sox to Win Over Foxes,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 31, 1933: 6; “Grey Sox, Detroit Divide Twin Bill,” Montgomery Advertiser, August 14, 1933: 6.

6 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015), 116-117.

7 Plott, 117.

8 Plott, 117.

9 “New Orleans Sees Two Major Nines This Week,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1935: 16.

10 There are no known interviews with Glover, nor do any newspaper articles yet uncovered suggest why he seems to have moved switched teams so frequently.

11 “No Hit No Run Game,” Bakersfield Californian, November 6, 1939: 14; “Bob Feller to Hurl Tonight for All-Stars Against Giants,” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 1939: 14.

12 See Richard J. Puerzer, “The 1939 Negro National League Championship Series: Baltimore Elite Giants vs. Homestead Grays,” in this volume.

13 “Doubleheader Marks Opening of Winter Baseball,” Van Nuys (California) News, October 5, 1939: 6.

14 “Negro Southpaw Blanks Kings,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1939: 30.

15 “Doubleheader Marks Opening of Winter Baseball.”

16 “Negro Southpaw Blanks Kings,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1939: 30.

17 William McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 200.

18 “Stars Here Sunday in NNL Opener,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 5, 1942: 21.

19 One looking at the final league standings as reported on Seamheads in early 2024 sees the Elite Giants (38-27) a full 13 games behind Homestead (54-17), but Baltimore Afro-American coverage of games in the final week of the season consistently expressed a dramatic fight for the pennant. After the Elites split a doubleheader on Sunday, September 6, the newspaper wrote, “The result of the day’s activities left the Elites still a game behind the league-leading Washington Homestead Grays, with only the Labor Day twin bill remaining on the schedule.” Art Carter, “Divide Sunday Twin Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 8, 1942: 19. The full-page eight-column headline on the same page proclaimed, “Grays Clinch Flag; Open World Series in D.C.,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 8, 1942: 19.

20 Art Carter “Elites Must Patch Cracking Infield,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 12, 1943: 25.

21 “Elite Giants May Lose Key Men,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 27, 1943: 18.

22 “Elites Break Even; Stage Set for Sunday Opening,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 5, 1945: 23.

23 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 455.

24 “Defi!,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 11, 1945: 26.

25 “Yanks Flash Sock When Badly Needed,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 28, 1946: 15.

26 “Bids for 2 Berths Refused,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 23, 1946: 16.

27 “Glover at Henryton,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 13, 1948: 24.

28 Kelcie Pegher, “The Little World Series of the West,” Carroll County Times (Westminster, Maryland), June 25, 2013. https://archive.ph/20131105015410/http://www.carrollcountytimes.com/news/local/demolition-begins-at-former-henryton.

29 “Ex-Baltimore Elite Giants Hurler Dead,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 12, 1948: 9.

Full Name

Thomas Glover

Born

February 11, 1913 at Montgomery County, AL (USA)

Died

June 7, 1948 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.