Indianapolis Hoosiers team ownership history

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

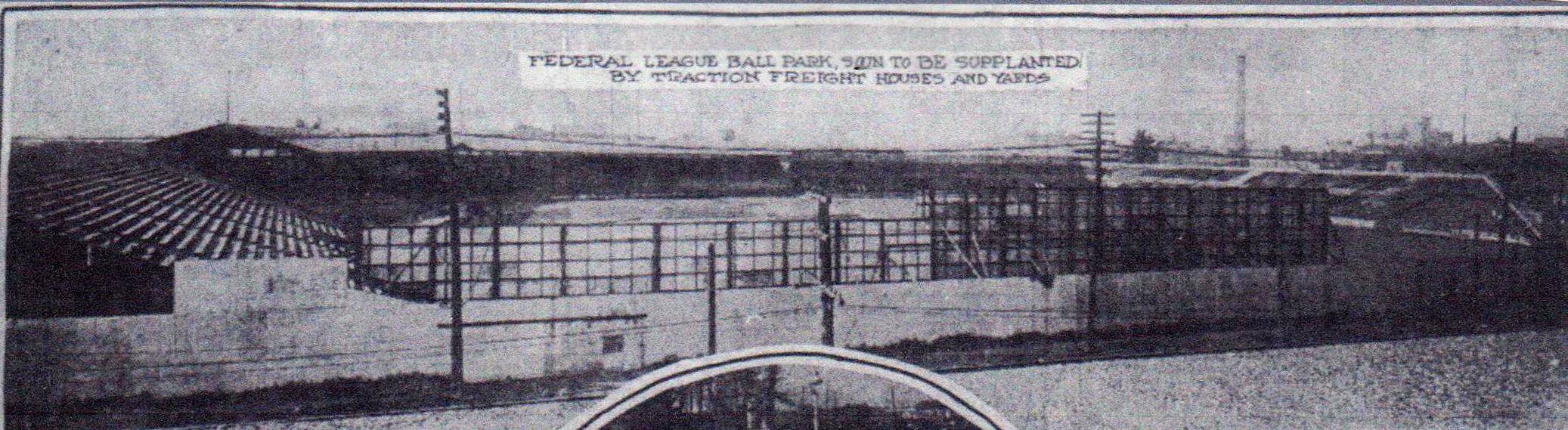

Federal League Park in Indianapolis, looking in from the right-field fence. (Indianapolis News, January 27, 1917)

Federal League Park in Indianapolis, looking in from the right-field fence. (Indianapolis News, January 27, 1917)

The city of Indianapolis has been home to four short-lived major-league franchises. The first two — the 1878 Indianapolis Blues of the National League and the 1884 Indianapolis Hoosiers of the American Association — were noncompetitive and disbanded after a single season. The National League Indianapolis Hoosiers (1887-1889) performed no better on the diamond but persevered under strong-willed club boss John T. Brush until the club was liquidated by the NL as a strategic measure in the run-up to the Players’ League War of 1890. This is the story of the final major-league club to call Indianapolis home — the Deadball Era Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Federal League.

Unlike its predecessors, this edition of the Hoosiers was an unqualified success on the field, capturing the Federal League pennant in the circuit’s inaugural campaign as an independent minor league in 1913. And when the outlaw Federals declared themselves a major league the following year, the Hoosiers repeated as league best.

Unhappily for investors in the Indianapolis Hoosiers, the club did not flourish at the turnstiles. At the conclusion of its 1914 championship season, the club was burdened with six-figure debt and teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. This made the franchise an inviting target for takeover and relocation. In March 1915 Hoosiers’ stockholders faced no viable option other than accede to a buyout offer tendered by oil tycoon Harry Sinclair, who removed the club to Newark, New Jersey. Once the papers were signed, Indianapolis as a major-league baseball city passed into history.

Indianapolis and the Formation of the Minor Federal League in 1913

In the decade after the liquidation of the Brush-led Indianapolis Hoosiers of the National League, the city found its footing as home to the Indianapolis Indians, an outstanding high minor-league club that captured Western League championships in 1895, 1897, and 1899. Indianapolis retained circuit membership when the WL changed its title to the American League the ensuing winter but was jettisoned when the American League proclaimed itself a major league for the 1901 season and placed franchises in Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, and Baltimore. After leading a stillborn attempt to revive the American Association as a major league that same spring,1 Indianapolis became a cornerstone franchise of a high minor league that assumed the American Association name.

By 1911, the American League had achieved parity, if not more, with the longer-established National League, and the game itself was enjoying widespread popularity. More than 6.5 million fans attended a major-league game that season, after which almost 180,000 more crammed into the grandstands to see the Philadelphia A’s defeat the New York Giants in a six-game World Series. This led John T. Powers, a Chicago baseball entrepreneur and the organizer of several minor-league circuits, to the belief that the time was ripe for the formation of a third major league. In January 1912 Powers publicly unveiled the Columbian League, an aspiring major league with franchises ticketed for Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Detroit, Milwaukee, and other Midwest cities.2

Disagreeably for Powers, his initiative soon had a rival: William A. Witman and his Eastern-city-based United States League, another wannabe major league.3 Seriously undermined by the USL competition, Powers’ circuit proved unable to sign playing talent or attract the financial support necessary to get the project off the drawing board. By mid-March, the Columbian League had collapsed.4

Undiscouraged, Powers revised his approach toward breaking into big-league baseball, downsizing his ambitions — at least for the short term. His efforts to form a new league continued but remained unpublicized until February 1913, when word leaked out that Powers had lined up backing for a new, non-major-league circuit to be based in Midwest cities.5 One of those cities was to be Indianapolis. Given that its population of 266,0006 was considerably less than that of Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland, and other proposed sites, Indianapolis was a superficially odd choice for inclusion in the new circuit, now called the Federal League. But by early 1913, Indianapolis civic and business leaders had become influential in the FL movement, although Powers remained at the helm.

When Federal League executive offices were filled, Powers was elected president but Indy residents manned the positions of league secretary (James A. Ross); treasurer (John A. George); and legal counsel (Edward E. Gates). Ross and George were also appointed to the Federal League board of directors.7 The Federal League was thereafter incorporated in Indianapolis under the laws of Indiana as a six-club circuit: Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati/Covington (Kentucky), and Indianapolis.8 The new FL, however, was not a signatory of Organized Baseball’s National Agreement and would therefore play as an independent, or outlaw, minor league in 1913.

Generally speaking, two models were employed for bankrolling the franchises of the Federal League. Most clubs were owned and operated by a small group of deep-pocketed capitalists who doubled as baseball enthusiasts. But Indianapolis attracted no such financial angels. Rather, the Indianapolis Federal Base Ball Company was a stock club, dependent upon the public purchase of shares in the franchise and incorporated in the state of Indiana after $75,000 in working capital had been raised from scores of individual investors.9 Prior to incorporation, club operations were overseen by hometown FL executive officers Ross and George, plus several other Indianapolis businessmen who invested in the new club.

Their immediate task was securing grounds for the Hoosiers. With Washington Park II securely leased by the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, the Hoosiers brain trust settled upon Riverside Beach Park and promptly set about siting a baseball stadium there.10 Once access to the grounds had been secured, acting club business manager Theodore Hewes dispatched a 65-man construction crew to commence construction of a 16,000-seat ballpark.11 Meanwhile, former major-league pitcher and one-time Indianapolis Indians manager Bill Phillips was engaged as field leader for the new club.12

With Opening Day on the horizon, the Indianapolis Hoosiers formally appointed its front office leaders, but the man tabbed as club president was an unforeseen choice: J. Edward Krause, a prosperous Indianapolis hotelier well known in city business, civic, and political circles but heretofore a stranger to the baseball scene.13 An able and energetic man, Krause admitted his lack of baseball expertise but assured observers that “there was nothing that he could not learn.”14 Doubling up their duties as FL front office executives were newly designated Hoosiers club secretary Ross and club treasurer George, while Hewes officially assumed the post of club business manager. Filling out the Indianapolis executive suite were club vice president Brandt C. Downey and club directors George, Hewes, Downey, Lynn B. Millikan, and Bert Essex.15

With Opening Day on the horizon, the Indianapolis Hoosiers formally appointed its front office leaders, but the man tabbed as club president was an unforeseen choice: J. Edward Krause, a prosperous Indianapolis hotelier well known in city business, civic, and political circles but heretofore a stranger to the baseball scene.13 An able and energetic man, Krause admitted his lack of baseball expertise but assured observers that “there was nothing that he could not learn.”14 Doubling up their duties as FL front office executives were newly designated Hoosiers club secretary Ross and club treasurer George, while Hewes officially assumed the post of club business manager. Filling out the Indianapolis executive suite were club vice president Brandt C. Downey and club directors George, Hewes, Downey, Lynn B. Millikan, and Bert Essex.15

The Indianapolis Hoosiers showed their competitive mettle with a 9-5 debut victory in Pittsburgh on May 6, 1913. But a contest of a different sort came a few days later with the club’s home opener back in Indianapolis. To put an upstart rival in its place, the American Association allowed the Indianapolis Indians to rearrange their schedule so a doubleheader against Louisville could played directly opposite the Hoosiers’ home opener.16 The head-to-head competition promptly resolved the issue of whether the newcomers were welcome in town. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston and 7,500 Indy baseball fans made their way into Riverside Beach Park to see the Hoosiers capture a 6-5 decision in 11 innings over Chicago.17 Blocks away at Washington Park II, only 2,000 attended the split of the Indians-Louisville doubleheader.

With Sunday baseball legal in Indianapolis, 18,507 fans crammed into Riverside Beach Park to witness the Hoosiers drop a 3-2 decision to Chicago the next day.18 But if the throngs attending the Hoosiers’ opening weekend inflated management’s gate expectations, the less than 1,000 fans who showed up for the final game of the Chicago series promptly deflated them.

Still, club President Krause was upbeat. “The people of Indianapolis proved the last few days that they are in favor of Federal baseball,” he declared to the press. “We want to assure them that we appreciate their position and will do our best to give them a club that is a winner. Parsimony will not be part of the club administration.” To demonstrate the bona fides of that declaration, Krause then announced that the Hoosiers’ ballpark “will be beautified. It will be sodded and there will be other changes in the playing field that will help out the standard of play.”19

As promised, the grounds at Riverside Beach Park were substantially improved over the following months. Likely more important to club fans, the Hoosiers played top-notch baseball. Behind steady pitching and the Federal League’s most potent attack (a league-leading .284 team batting average), Indianapolis went 74-45 (.625) and cruised to the inaugural FL pennant, a full 10 games better than the second-place Cleveland Green Sox (64-54, .542).20 Success on the diamond, however, was not matched at the gate. The club lost money, but not enough to discourage plans to take the field for the 1914 season.21 That campaign would see Indianapolis host a major-league baseball club for the fourth and final time.

The Indianapolis Hoosiers, Champions of the 1914 Federal League

Federal League founder John T. Powers did not get to guide his offspring to major-league status. The wealthy and ambitious capitalists whom he had recruited for FL club ownership had grown impatient with Powers’ cautious, nonadversarial approach to achieving big-league status over time. They wanted to achieve that status quickly and were spoiling for a fight with the Organized Baseball establishment. To that end, Powers was deposed as FL president at a league meeting in August 1913.22

From then on, the outlaw Feds would be led by dynamic James A. Gilmore, co-owner of the Chicago Chifeds. Under Gilmore’s leadership, the Federal League expanded to an eight-club circuit for the 1914 season, planting franchises in the major Eastern venues of Brooklyn, Baltimore, and Buffalo and declaring itself a third major league. To obtain the necessary on-field talent, the Feds ignored the provisions of the National Agreement designed to safeguard player contracts from tampering. They began raiding National and American League rosters.

Although the club had lost a reported $12,000 in 1913,23 the leadership of the Indianapolis Hoosiers was enthralled by the prospect of their team being elevated to major-league status. As club president of the reigning FL champions, J. Edward Krause soon assumed the role of prominent league spokesman. In the run-up to a meeting of FL club owners, Krause made the outlaws’ intentions public. “It will be war to the hilt,” he declared. “… There will be no half-measures henceforth. The Federal League has come to stay.”24 To upgrade the circuit’s playing talent, Federal League club owners would open their wallets and go after established big-league stars. “We have the money and the ambition to succeed in this game,” Krause continued. “The money we have will tempt the ball players and we expect to be able to offer our patrons next year first class attractions.”25

But if Indianapolis was going to participate actively in FL plans, the club first needed to get its finances in order. At a franchise reorganization meeting conducted in mid-November, Krause and the other club officers were all reelected to their posts. A plan was then adopted to replenish the depleted club treasury via the issuance of $200,000 in new stock.26 In time, the ranks of Indianapolis Hoosiers shareholders swelled to near 400, and the club’s large and unwieldy ownership structure made raising capital quickly and as needed during the season difficult. But for the time being, the influx of new money provided the funds needed to keep the franchise operational. It also furnished the financing needed for the new ballpark that the Federal League desired of Indianapolis and several other clubs.

As the league’s October 31 ballpark deadline approached, club officials announced the location of the Hoosiers’ new playing grounds: a swath of Greenlawn Cemetery, a venerable burial ground situated in downtown Indianapolis.27 For the short term, however, the cemetery property was not bought outright. Rather, the property was leased “with privilege to purchase” for five years at $4,200 annually. Nor was the new ballpark to be a club asset. Rather, club shareholders were given a five-year option to purchase the structure for $76,000.28

Under the direction of contractor Lynn B. Millikan, himself a member of the Hoosiers board of directors and a substantial club investor, construction of Federal League Park commenced at a furious pace. Grandstand construction costs were estimated at $75,000,29 and total ballpark expenditures would eventually creep over the $100,000 mark. In the meantime, club management had to acquire upgraded playing talent.

Club President Krause gave public assurance to National and American League players recruited by the Feds that they would be defended against reserve clause-based litigation. “We think the reserve clause is invalid,” Krause proclaimed, “and believe that we can secure such a decision if the matter is taken to court.”30 But the actual signing of playing talent was delegated to holdover Hoosiers manager Bill Phillips and new business manager Bill Watkins, an astute baseball executive whose long connection to Indianapolis dated back to playing second base for the 1884 Hoosiers of the then-major league American Association.31

Like most FL clubs, the Hoosiers had little luck attracting established major leaguers. But Indianapolis succeeded in wresting a promising St. Louis Cardinals prospect stashed with the American Association Indianapolis Indians: outfielder Benny Kauff, signed by the Hoosiers for double his $2,000 Indians salary. Kauff would go on to become “the Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” leading the circuit with a .370 batting average in 1914. But well before that, the Hoosiers had to deal with local repercussions of the Kauff signing.

Like most FL clubs, the Hoosiers had little luck attracting established major leaguers. But Indianapolis succeeded in wresting a promising St. Louis Cardinals prospect stashed with the American Association Indianapolis Indians: outfielder Benny Kauff, signed by the Hoosiers for double his $2,000 Indians salary. Kauff would go on to become “the Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” leading the circuit with a .370 batting average in 1914. But well before that, the Hoosiers had to deal with local repercussions of the Kauff signing.

Because the Federal League did not abide by the National Agreement, there was little recourse within baseball available to infuriated Indians club owner James C. McGill. And legal precedent dating back to the Players’ League War of 1890 discouraged the filing of a contract-based lawsuit. Instead, McGill seized upon construction reuse of wooden seating salvaged from Riverside Beach Park, claiming its utilization in the Federal League Park grandstand violated city fire ordinances. The Hoosiers’ building permit should therefore be revoked.32 But with local officialdom solidly in the Hoosiers’ corner — Indianapolis Mayor Joseph E. Bell had presided over ballpark ground-breaking ceremonies only a few weeks earlier — McGill’s complaints were given short shrift.33

More vexing was the slowdown in delivery of needed building material occasioned by labor problems at a Bethlehem Steel Company plant. Notwithstanding construction snags, by late April the Indianapolis Hoosiers had a modern single-tier, state-of-the-art concrete-and-steel ballpark to call home. The question then became how many of Federal League Park’s almost 23,000 seats the Indianapolis Hoosiers would be able to fill.

On April 23, 1914, major-league baseball returned to Indianapolis for the first time in 25 years. Preceding the game was a half-mile-long parade through downtown to the ballpark, complete with marching bands and festooned automobiles carrying local dignitaries and officials from the two opposing ballclubs.34 Upon arrival, a crowd of about 18,000 paid their way into Federal League Park to see the Hoosiers face the St. Louis Terriers. Following a welcoming speech by club President Krause, Governor Ralston took the mound to throw a ceremonial first pitch — high and outside — to Mayor Bell.

Those in attendance then settled down to witness a scoreless pitching duel between Hoosiers ace Cy Falkenberg and Terriers left-hander Hank Keupper through eight innings. A final-inning Terriers rally proved the difference in a 3-0 St. Louis victory that disappointed hometown fans, but otherwise did little to detract from the success of the ballpark opening.35 Meanwhile blocks away at Washington Park II, only 1,500 fans watched the rival Indianapolis Indians drop a 3-0 decision to the Louisville Colonels.36

In the main, the 1914 season was déjà vu for the Indianapolis Hoosiers. As in the year before, the club enjoyed success on the playing field but insufficient patronage at the ballpark. Complete and reliable attendance figures do not exist for the Federal League. But for the 15 specific Indianapolis home dates for which Retrosheet provides attendance numbers, the Hoosiers lured an average crowd of 2,677 to their 23,000-seat ballpark.37 This draw made the club unable to meet expenses as the season progressed. The problem was exacerbated by Indianapolis’s large and fractious body of stockholders. Raising needed capital in-house during the season was a cumbersome process and the response to an in-season call for further stockholder contribution to the club treasury was underwhelming. Indeed, incessant stockholder demand for a promised 6 percent dividend on club shares served to diminish the Indianapolis treasury rather than replenish it.

To keep the Hoosiers afloat while the team drove to the 1914 Federal League pennant, club officials dipped into their own pockets to the tune of $26,000 but could not wipe out the club’s operating deficit. To do so, they were obliged to privately borrow an additional $10,000 from Robert B. Ward, lead owner of the FL Brooklyn Tip-Tops.38 The Indianapolis franchise also became indebted to the Federal League office.39

For the time being, the club’s financial turmoil was not publicized. And it did not subvert the quality of Hoosiers performance on the diamond. Paced by an MVP-like season by Benny Kauff (who in addition to his league-leading .370 batting average paced the circuit in seven other offensive categories40) and standout pitching by 25-game winner Cy Falkenberg, Indianapolis went 88-65 (.575) and captured the maiden flag of the Federals as a major league.

Hoosiers brass delighted in the championship, hosting a late-September celebration at Federal League Park complete with pregame parade and floral tributes presented to the players. Pennant-winning manager Bill Phillips was bestowed with a large silver loving cup.41 The festive occasion, however, soon gave way to harsh financial realities. Unbeknownst to the crowd, the continued existence of the Indianapolis Hoosiers was in jeopardy.

The Removal of the Indianapolis Franchise to Newark

Once the 1914 campaign had been completed, Hoosiers officials set about their usual offseason activities, cloaking the club’s gathering financial collapse with business-as-usual exercises. But first they were obliged to dismiss a report out of Chicago that intimated that the Indianapolis franchise was ticketed for New York. The “Indianapolis berth is secure … as long as there is a Federal organization, since they hold a perpetual franchise,” the concerned hometown Indianapolis News was assured by Hoosiers leadership.42

Upon returning from a league meeting in Manhattan, club President Krause had even stronger words, declaring that “all talk of Indianapolis losing its [Federal League] berth … was absurd.”43 He let slip, however, that there was a backstage move afoot to transfer the league’s weak Kansas City franchise to New York.

During the ensuing months, news emanating from Indianapolis consisted of the customary hot-stove palaver about player moves, spring-training preparations, 1915 season expectations, and the like. Meanwhile on the business front, a façade of prosperity was erected. At a December meeting of club shareholders, the newly installed board of directors (Krause, Ross, George, Gates, and newcomer Fay Murray) sought authorization to exercise the club option to purchase the Federal League Park grounds outright. To finance the purchase, a $200,000 mortgage secured by a new issue of club stock was to be procured. The stock offering would be extended “pro rata to the club stockholders and if not entirely subscribed for, they will be offered to the public upon the same terms.”44

On behalf of the club leadership, club President Krause expressed optimism, stating that he felt “confident that the deal for the purchase of the land on which our park is located will go through. All of us are anxious to show the people of the city that we are connected with a permanent institution and we feel that this is an opportunity we should not overlook.”45

As hoped, the scheme was approved by club stockholders, and at least $35,000 worth of new stock had been subscribed within days of offering, Krause claimed.46 But weeks later, the unexpected resignation of stalwart club secretary James A. Ross — the prominent local attorney had “deemed it necessary to give all of his time to the practice of law” — signaled that perhaps all was not well in Indianapolis.47 Perhaps more important, the Indianapolis stock issue generated little interest from investors, the earlier announcement of club President Krause notwithstanding.48 Not only was the purchase of the Federal League Park property scotched. The club remained in arrears regarding payment of its debts to Brooklyn and the FL office.

In early February, a visit to Indianapolis by Federal League chief James A. Gilmore ramped up speculation that the Indianapolis franchise was imperiled. But when he emerged from a closed-door meeting with Krause and other Hoosiers officials, Gilmore maintained that no more than unspecified Indianapolis “club affairs” had been discussed.49 Despite suggestions to the contrary (attributed to malicious sources connected to Organized Baseball), reports that the Indianapolis franchise was moving were “absolutely ridiculous and without foundation,” declared Gilmore.50 “Absolutely nothing to the rumors” of transfer, echoed Krause. “We have planted ourselves here with the assurance that as long as the Federal League continued to do business, Indianapolis would be a member of the circuit. We have taken root here and we are growing.”51

Instead, Kansas City was the Federal League club that would be transferred east. Meanwhile, Charles Weeghman, boss of the FL Chicago Whales, was identified as source of an early March report that the finances of the Indianapolis club were to be underwritten by an unidentified “millionaire.”52 Although the Weeghman tale was far-fetched, it coincided with an ominous development in the Indianapolis front office. Club President Krause, vacationing in Florida for most of the winter, effectively relinquished leadership of the franchise.53

As it turned out, events in Kansas City proved the proximate cause of Indianapolis’s undoing as a Federal League member. Like the Hoosiers, the Kansas City Packers were an underfinanced stock club heavily in debt to Brooklyn owner Ward and the league treasury.54 In addition, Kansas City had been a poor draw at the gate and a distant also-ran in the 1914 pennant chase. The Packers were, therefore, a prime candidate for the relocation of a Federal League club to the New York area as desired by FL leaders and newly arrived franchise suitor Harry Sinclair, a baseball-minded oil tycoon.55

Anxious for the infusion of Sinclair’s reputed $10 million fortune into their ranks, FL brass had approved his takeover of the Packers and their removal to the new ballpark he was building on the outskirts of Newark. But such plans were stymied by recalcitrant stockholders in the Kansas City club who obtained a temporary injunction from a sympathetic federal judge. With the 1915 season approaching and time of the essence, FL President Gilmore and Sinclair abandoned the offensive against Kansas City and reset their sights on an alternate target — the Indianapolis Hoosiers.56

At that moment, the Indianapolis franchise was in desperate financial straits. Unbeknownst to Gilmore and Sinclair, club management had privately discharged the debt owed to Brooklyn club boss Ward by assigning the contracts of Kauff and Falkenberg to the Tip-Tops. But with the winter’s stock issuance a bust, Indianapolis was almost entirely without funds for the coming season.

At that moment, the Indianapolis franchise was in desperate financial straits. Unbeknownst to Gilmore and Sinclair, club management had privately discharged the debt owed to Brooklyn club boss Ward by assigning the contracts of Kauff and Falkenberg to the Tip-Tops. But with the winter’s stock issuance a bust, Indianapolis was almost entirely without funds for the coming season.

On March 18, 1915, the Federal League’s executive committee (Gilmore, Ward, and Buffalo club President William E. Robertson) arrived in Indianapolis demanding that the franchise be surrendered for failure to satisfy its outstanding debt to the league treasury.57 At first the club directors resisted but their position was undermined by internal forces. Pliny W. Bartholomew, a former state court judge and a modestly-invested Hoosiers shareholder, filed a lawsuit seeking to have the Indianapolis franchise declared insolvent and for a receiver to be appointed for stockholder protection.58

At a hastily convened meeting of club stockholders, a formal takeover proposition received from FL President Gilmore was considered by those assembled. In return for relinquishment of the franchise to the league, outstanding indebtedness to Hoosiers creditors would be assumed by incoming club owner Harry Sinclair. For their part, FL officials would forgive the Indianapolis debt to the FL treasury and otherwise hold stockholders harmless for miscellaneous franchise liabilities. (But club directors would not be reimbursed the $26,000 in personal funds expended to keep the Hoosiers going late in the 1914 season.) The league would also cover the $4,200 rental due and owing on Federal League Park for the coming season. When put to a vote, the 394 club stockholders present accepted the proposition unanimously.59 And with that, the Indianapolis Hoosiers passed into history.

The relocation of the franchise was soon complicated by new FL magnate Sinclair’s discovery that Kauff and Falkenberg had been optioned to Brooklyn. Infuriated, Sinclair threatened to walk away from the Federal League if the transfers were not rescinded, but in time a compromise was reached. Kauff would become a Tip-Top in satisfaction of the Indianapolis debt owed Brooklyn club boss Ward, but Falkenberg would remain on the roster to anchor the pitching staff of Sinclair’s newly christened Newark Peppers. Also making the trip to Newark were holdover field manager Bill Philips and assistant business manager Steve Harker.

But for the others connected to the operation of the Indianapolis Hoosiers, their encounter with major-league baseball had come to its end. Nor was Indianapolis’s Federal League Park long bound for existence. Operated by a court-appointed receiver and home to local semipro, Black, college, and amateur baseball clubs during the summers of 1915-1916, the ballpark site was purchased by a Midwest railroad line in late November 1916.60 The following April, the handsome new ballpark was razed to make room for erection of a freight terminal. The last tangible vestiges of the Federal League’s Indianapolis Hoosiers disappeared with it.

BILL LAMB spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey. He is the editor of “The Inside Game,” the newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee and the author of “Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation” (McFarland, 2013). He is also the 2019 recipient of the Bob Davids Award, SABR’s highest honor.

Sources

The information imparted above is derived largely from the author’s previous writings on Federal League-related subjects and the newspaper articles specified in the endnotes. General sources included the following:

Levitt, Daniel R. The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2012).

Okkonen, Marc. The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League (Garrett Park, Maryland: SABR, 1989).

Wiggins, Robert Peyton. The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of the Outlaw Major League, 1914-1915 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009).

Notes

1 The public face of this third and final attempt to revive the American Association as a major league was Indianapolis Indians manager/co-owner Bill Watkins, widely perceived as a catspaw for John T. Brush, then majority owner of the National League Cincinnati Reds. For more on the Indianapolis role in the AA revival effort, see Bill Lamb, “Thrice Stillborn: Turn of the Century Attempts to Resurrect the Once-Major American Association,” Base Ball 11: New Research on the Early Game (McFarland, 2019): 155-161.

2 For more, see Bill Lamb, “John T. Powers: Minor League Organizer and Founder of the Federal League,” The Inside Game, Vol. XXI, No. 1 (February 2021): 7-8.

3 For more on Witman and the USL, see Bill Lamb, “Gotham’s Unknown Nine: The New York Knickerbockers of the United States League,” The Inside Game, Vol. XVIII, No. 5 (November 2018): 21-25.

4 Witman’s eight-club United States League took the field in April 1912 but, plagued by insufficient financing and fan disinterest, the USL abandoned play in June. An effort to restart the USL in 1913 also quickly collapsed.

5 “Invasion by Outlaw League Likely to Materialize in 1913,” Calumet (Michigan) News, February 7, 1913: 8; “Columbian League President in Town,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, February 12, 1913: 12; “Columbian League President in G. Raps,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, February 14, 1913: 7.

6 In March 1913, the population of Indianapolis was estimated at 266,935, per “Indianapolis Is Growing,” Indianapolis Star, March 20, 1913: 18. The proposed Federal League site nearest in size to Indianapolis was Cincinnati, with a population of 364,443. See “Plan of New Federal League,” Indianapolis Star, March 9, 1913: 42.

7 “Federal League Is Formed in the West,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1913: 1; and “Local Men Are Made Officers of League,” Indianapolis Star, March 9, 1913: 41. Ross and Gates were prominent Indianapolis attorneys. George was a prosperous local coal dealer.

8 “Four County Officers in It,” Indianapolis News, March 10, 1913: 16; and “Federal League Men Will Pick Park Site,” Indianapolis Star, March 10, 1913: 14. See also, “President Powers on Ground in Cincinnati,” Indianapolis News, March 15, 1913: 12.

9 “Federal Club Files Organization Papers,” Indianapolis News, April 14, 1913: 10; “Federal League Club Is Organized,” Indianapolis Star, April 15, 1913: 10.

10 “Federal Promoters to Inspect Site for Park,” Indianapolis News, March 15, 1913: 10. Previously, Riverside Park Beach had been the sight of local boxing matches and track and field meets.

11 “Federal Promoters to Inspect Site for Park”; “Riverside Beach Almost Finished,” Indianapolis Star, April 29, 1913: 10. The newly constructed Riverside Beach Park is not to be confused with Riverside Park (aka Washington Park I), an undersized wooden ballpark also located in downtown Indianapolis and built in 1904.

12 “Bill Phillips Will Manage Indianapolis,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 7, 1913: 12. Other name managers hired by fledgling FL clubs included Cy Young (Cleveland); Deacon Phillippe (Pittsburgh); Chick Frazier (St. Louis), and George “Admiral” Schlei (Cincinnati/Covington).

13 “J. Edward Krause New Federal Club Magnate,” Indianapolis News, April 19, 1913: 8.

14 “Indianapolis Moguls See Federal Opening,” Indianapolis News, May 6, 1913: 12. For more on Krause, consult his BioProject profile.

15 “J. Edward Krause New Federal Club Magnate,” Indianapolis News, May 6, 1913: 12.

16 “Two Leagues Will Start a Baseball War,” Pensacola (Florida) Journal, May 11, 1913: 8.

17 Fred Turbyville, “Fans Pronounce New League O.K.,” Indianapolis Star, May 11, 1913: 32.

18 “18,507 Rampant Bugs See Local Feds Lose,” Indianapolis Star, May 12, 1913: 8.

19 “Plan Improvements,” Indianapolis Star, May 12, 1913: 9.

20 The interleague rival Indianapolis Indians went 68-99 (.407) and finished dead last in the eight-club American Association’s final standings. The Indians also drew poorly, attracting only 1,400 fans per home game.

21 The extent of the financial loss suffered by Indianapolis Hoosiers shareholders is uncertain, but one Federal League historian places the loss suffered by the six-club Federal League as a whole at a staggering $750,000 in 1913. See Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of the Outlaw Major League, 1914-1915 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 18.

22 For more on Powers’ ouster as Federal League president, see Bill Lamb, “John T. Powers: Minor League Organizer and Founder of the Federal League,” The Inside Game, Vol. XXI, No. 1 (February 2021): 7-8.

23 According to New York Giants club President Harry Hempstead, an Indianapolis department store magnate whom the Hoosiers had inadvertently solicited. See Indianapolis News, January 23, 1914: 16.

24 Ed Ash, “Federal League Will Wage War on the Majors,” Indianapolis Star, October 15, 1913: 8.

25 Ash, “Federal League Will Wage War”; “Federals Are Coming Downtown Next Year,” Indianapolis News, October 23, 1913: 10.

26 “Hoosier Feds to Train in South,” Indianapolis Star, November 13, 1913: 7. The stock issue was to be apportioned into $150,000 in common stock, $50,000 preferred.

27 Ed Ash, “Federal League Magnates Here and Ready for War,” Indianapolis Star, November 1, 1913: 11. The Hoosiers were following the example of a Midwest railroad that had recently acquired another Greenlawn Cemetery parcel for construction of a locomotive repair shop and roundabout.???? Does Bill mean a turntable?

28 A century later, the financing behind the construction of the new Indianapolis ballpark is murky, difficult to pin down. Nor can the titleholder of Federal League Park, aka Greenlawn Park, be identified with certainty. For more on the events attending the birth of the ballpark, see Bill Lamb, “Federal League Park, Indianapolis,” Palaces of the Fans, June 2021: 8.

29 “Club Awards Contract,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), January 18, 1914: 21; “The Hoosiers’ New Park,” Indianapolis Star, January 18, 1914: Sport Section 1.

30 “Local Federal Leader Asserts League Will Protect Players Against All Legal Proceedings,” Indianapolis Star, December 29, 1913: 9; “Federal League to Back Players,” Lake County Times (Hammond, Indiana), December 29, 1913: 4.

31 “W.H. Watkins to Be the Business Manager of Feds,” Indianapolis Star, February 19, 1914: 1. After his playing career had been short-circuited by a near-fatal beaning, Watkins went on to manage the 1887 World Champion Detroit Wolverines of the National League and the Western League champion Indianapolis Hoosiers of the 1890s. After Indianapolis was squeezed out of the American (née Western) League in 1901, Watkins founded the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the new high-minor American Association and remained at the helm until he sold the club in May 1912.

32 “Tribe Chieftain Dons Warpaint,” Indianapolis Star, February 3, 1914: 1.

33 “Realty Transfers,” Indianapolis Star, February 14, 1914: 11.

34 “Fed Parade Is Some Stunt with Bands and Everything,” Indianapolis Star, April 24, 1914: 13.

35 “Hoosiers Ready to Square Away after Setback in Opener,” Indianapolis News, April 24, 1913: 24.

36 “Rooters Excited Over Early Speed of Tribe,” Indianapolis Times, April 24, 1914: 10.

37 In the offseason, the improbable claim that Indianapolis “finished third” in FL attendance behind only Chicago and Baltimore was circulated. See “Federal Officials Say Indianapolis Is Secure,” Indianapolis News, October 3, 1914: 11.

38 Wiggins, 189, citing “Feds New Angels Prove Stubborn,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1915: 5. Federal League historian Wiggins places the Hoosiers’ 1914 operating deficit at an unsustainable $102,000.

39 For a deeper look at the financial crisis facing the Indianapolis Hoosiers, see Wiggins, 189-191. See also, Daniel R. Levitt, The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 200-204.

40 In addition to batting average, Kauff led the FL in runs (120) base hits (211), doubles (44), stolen bases (75), on-base percentage (.447), OPS (.981), and total bases (305).

41 “Hoosier Fans to Celebrate in Honor of Bill Phillips,” Indianapolis News, September 17, 1914: 12.

42 “Federal Officials Say Indianapolis Is Secure,” Indianapolis News, October 3, 1914: 11.

43 “Claims Indianapolis Will Retain Fed Berth,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, October 28, 1914: 10.

44 “Hoosier Feds to Close Option on Park Ground,” Indianapolis News, December 10, 1914: 12.

45 “Expect to Buy Park,” Indianapolis Star, December 14, 1914: 8.

46 “Krause to Hold Up Gift for Fans Until after Christmas,” Indianapolis Star, December 24, 1914: 9.

47 “Ross Resigns as Secretary of Hoofeds,” Indianapolis Star, January 11, 1915: 12. Ross had been an influential figure in Federal League affairs since the league’s inception in early 1913, and his departure was a blow to the stability of its Indianapolis franchise.

48 Wiggins, 190.

49 “Gilmore Holds Secret Meeting with Krause,” Indianapolis News, February 11, 1915: 10.

50 “Hoofed Transfer Not Considered, Says Gilmore,” Indianapolis Star, February 12, 1915: 10; “Hoofeds Not to Move,” South Bend (Indiana) News-Times, February 14, 1915: 7.

51 Jack Veiock, “Indianapolis Items,” Sporting Life, February 20, 1915: 10.

52 “Wealthy Backer Is Found for Hoofeds?” Indianapolis Star, March 2, 1915: 8.

53 When Indianapolis affairs reached crisis point in mid-March 1915, local newspapers referred to Krause as former president of the Hoosiers. See Ralston Goss, “Up to Stockholders Whether Hoofeds Shall Remain Here,” Indianapolis Star, March 21, 1915: 45; and “Fed Champs’ Transfer in a Deadlock,” Indianapolis Star, March 20, 1915: 10.

54 Just as wealthy Cleveland club owner Charles W. Somers had financially assisted underfunded competitors in the fledgling American League of 1901, well-heeled Brooklyn Tip-Tops owner Robert B. Ward had discreetly shored up the finances of several fiscally troubled Federal League franchises.

55 Sinclair’s interest in baseball extended back to co-ownership of a franchise in the lowly 1906 Kansas State League. His desire to enter ranks of major-league club owners, however, had previously been frustrated.

56 “Kaycee Suit Decision Delays Fed Schedule,” Indianapolis News, March 16, 1915: 12. The events attending the relocation of the franchise are outlined in this project’s team ownership history of the Newark Peppers. For more detail, see Wiggins,186-191, and Levitt, 193-205.

57 “Gilmore Demands Hoosier Franchise,” Indianapolis News, March 19, 1915: 18.

58 “Fed Champs’ Transfer in a Deadlock,” Indianapolis Star, March 20, 1915: 10. Bartholomew held $500 in Indianapolis Hoosiers common stock and $500 preferred.

59 “Hoosier Feds Will Go to Newark, N.J.,” Indianapolis News, March 24, 1915: 14; “Stockholders Agree to Sell Hoofeds to the League,” Indianapolis Star, March 24, 1915: 8. See also, Wiggins, 190.

60 “Traction Lines to Build $400,000 Freight Depot,” Indianapolis News, November 30, 1916: 14; “Traction Lines Buy Federal Ball Park,” Indianapolis Star, November 30, 1916: 1.