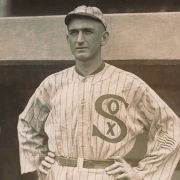

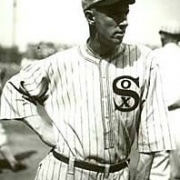

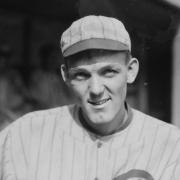

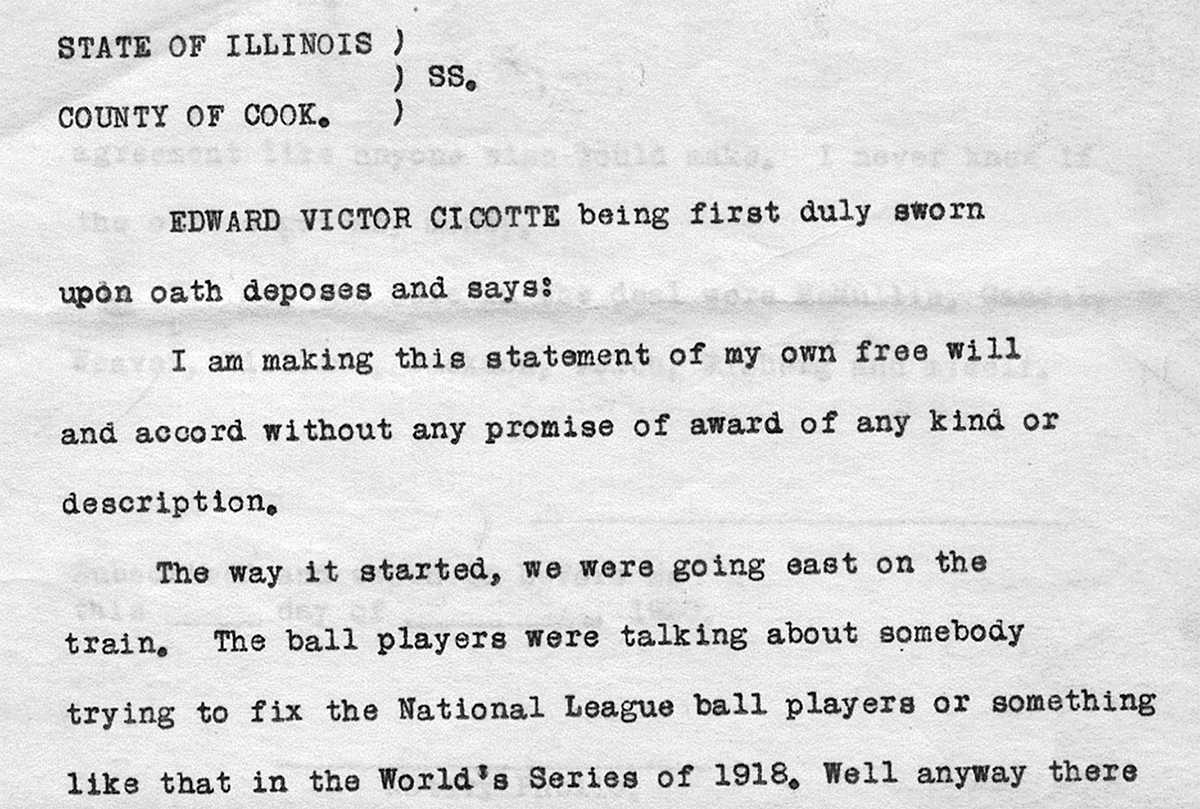

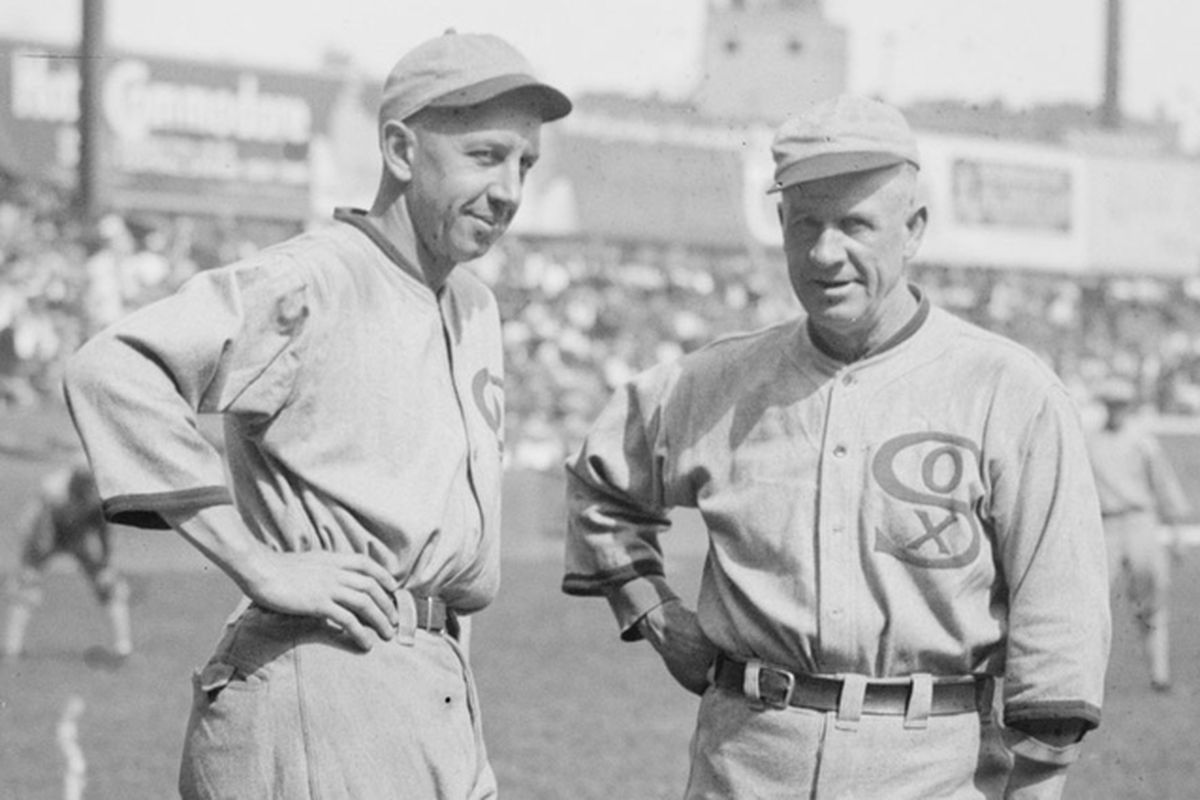

The Black Sox trial — baseball’s Trial of the Century — took place 100 years ago in 1921. Eight members of the Chicago White Sox, along with some of the gamblers who bribed them, were charged with conspiracy to fix the 1919 World Series, which the heavily favored Sox lost to the Cincinnati Reds.

For six weeks during the summer of 1921, baseball’s fallen stars — including Shoeless Joe Jackson, one of the greatest pure hitters the game has ever seen — gathered in a Chicago courtroom to await their fate. Their criminal trial made front-page headlines across the nation. Today, it’s unusual to see any transgression by an athlete, on or off the field, play out fully in the legal system. Baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, preferred that the game take care of its business outside the courtroom. After the Black Sox players and gamblers were acquitted by the jury on August 2, 1921, in a verdict that surprised many observers, Landis showed he would rule the game with an iron fist by immediately banning the players from ever appearing in the major leagues again.

Gambling in baseball was a hot-button issue in the early 20th century, just as it is now in the 21st century. Landis was hired by major-league owners with a mandate to clean up a corrupt game. Before the 1919 World Series scandal erupted, players and front-office executives were known to openly bet on their own teams (both for and against) and bettors were allowed to operate freely in major-league ballparks. Fans could attend a game at Wrigley Field in Chicago or Fenway Park in Boston and place a bet on the next pitch from their seat — a scenario that would not look out of place at a ballpark in 2021, given the growing world of legalized sports gambling.

The Black Sox trial has been portrayed in popular culture as a chaotic affair, plagued by the same forces of corruption and underworld shenanigans that would turn Prohibition-era Chicago into a caricature of itself for decades to come. Eliot Asinof’s best-selling book Eight Men Out, and John Sayles’s film by the same name, cast the prosecuting attorneys as bumbling fools and hinted at backroom deals between gamblers and baseball officials. Little of that has proven to be true.

In 2007, researchers gained access to thousands of pages of legal documents from the Black Sox grand jury, criminal trial, and civil lawsuits, which were acquired at auction by the Chicago History Museum and then made available to the public. These files and other primary sources, such as player salary contract cards, that have come to light in recent years have given us a better understanding of what happened 100 years ago.

— Jacob Pomrenke

- Read more: “A Summary of the Black Sox Scandal: What We Know Now,” by Bill Lamb

Eight Myths Out

In 2019, SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Committee shed light on the biggest myths about the fixing of the 1919 World Series, from Charles Comiskey’s reputation as a cheapskate owner who paid his players poorly to the fictitious hired hitman known as “Harry F.” to the “solid wall of silence” that participants allegedly engaged in afterward.