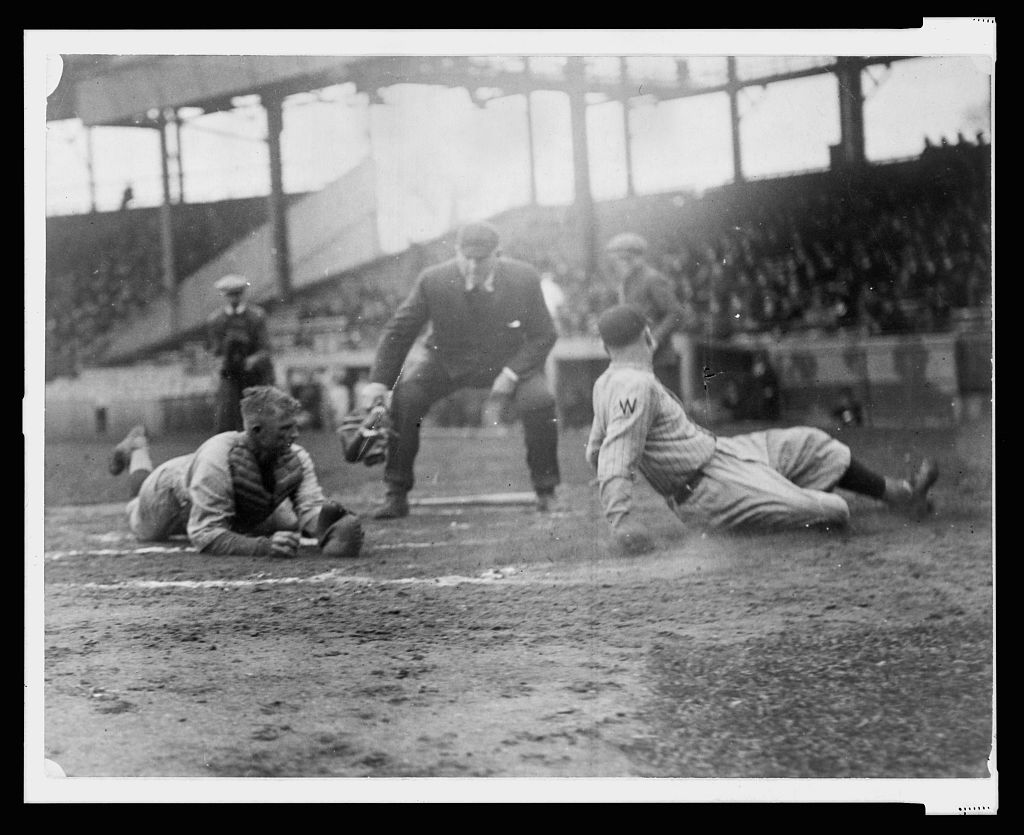

Baseball was on the verge of a “seismic shift in how the game was played in 1921,” according to Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg in their award-winning book, 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York. The sport was moving from “low-scoring contests dominated by pitching to a power game with more hits, runs, and home runs.” Baseball’s Deadball Era was at an end. The Lively Ball Era was here to stay.

Debates that were playing out in baseball in 1921 have resurfaced a century later, showing how the game continually reinvents itself, and can cycle back on previous patterns. The history of the game often boils down to the battle between pitching and hitting. In 1921, hitting was gaining the upper hand, helped by some rule changes. And the fans responded with rising attendance. Today in 2021 pitching has the upper hand, and baseball is looking at ways to adjust this imbalance.

Debates that were playing out in baseball in 1921 have resurfaced a century later, showing how the game continually reinvents itself, and can cycle back on previous patterns. The history of the game often boils down to the battle between pitching and hitting. In 1921, hitting was gaining the upper hand, helped by some rule changes. And the fans responded with rising attendance. Today in 2021 pitching has the upper hand, and baseball is looking at ways to adjust this imbalance.

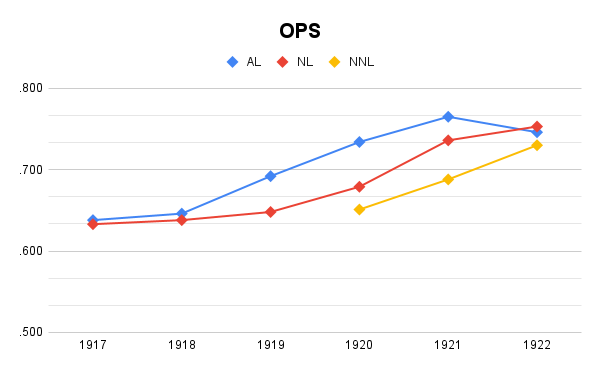

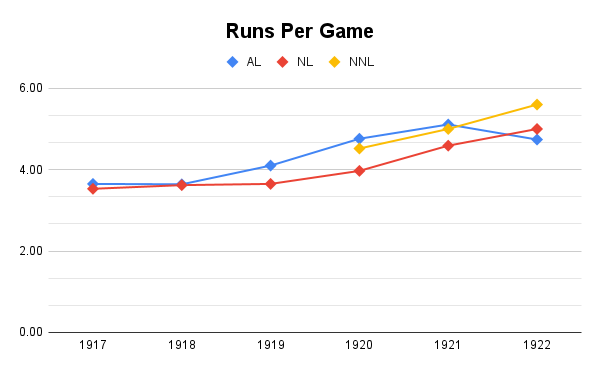

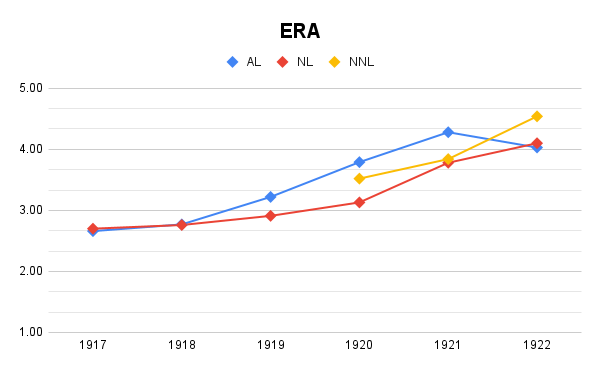

In February 1920 — in an effort to shift the game away from defense toward offense — baseball’s owners decided to ban “freak pitches,” including the spitball, mud ball, and any others thrown with foreign substances applied to the ball. Pitchers had to learn how to master other pitches (including the curveball), and hitters grew more comfortable in the batter’s box. The death of Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman in the late summer of 1920 reaffirmed baseball’s commitment to keep fresh, clean, and bright balls in play throughout the game. The success and popularity of Babe Ruth encouraged other hitters to swing for power from the end of the bat. Statistics from the 1921 season saw batting averages, slugging percentages, and earned-run averages continuing to rise, confirming that the 1920 numbers were not an anomaly. The 1920s would indeed be an era of offense, the Lively Ball Era.

In an echo of the 1920s, a 2021 headline in the Washington Post proclaimed, “How Baseball’s War on Sticky Stuff is Already Changing the Game,” while an article in the New York Times outlined how umpires were beginning to crack down in their enforcement of rules against pitchers’ use of foreign substances.

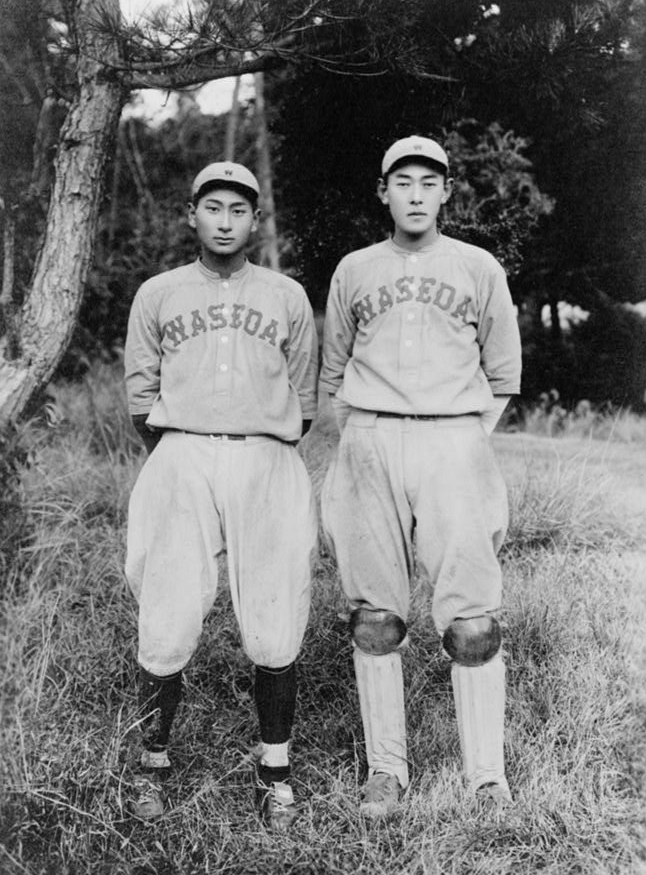

The 1921 season also marked the rise of the New York Yankees, who reached their first World Series. Led by Babe Ruth, they were challenging the popularity of manager John McGraw and his New York Giants. Organized Baseball also transformed in other significant ways that year. The game became more international — with tournaments taking place between American and Japanese teams — and with changes to the business of baseball.

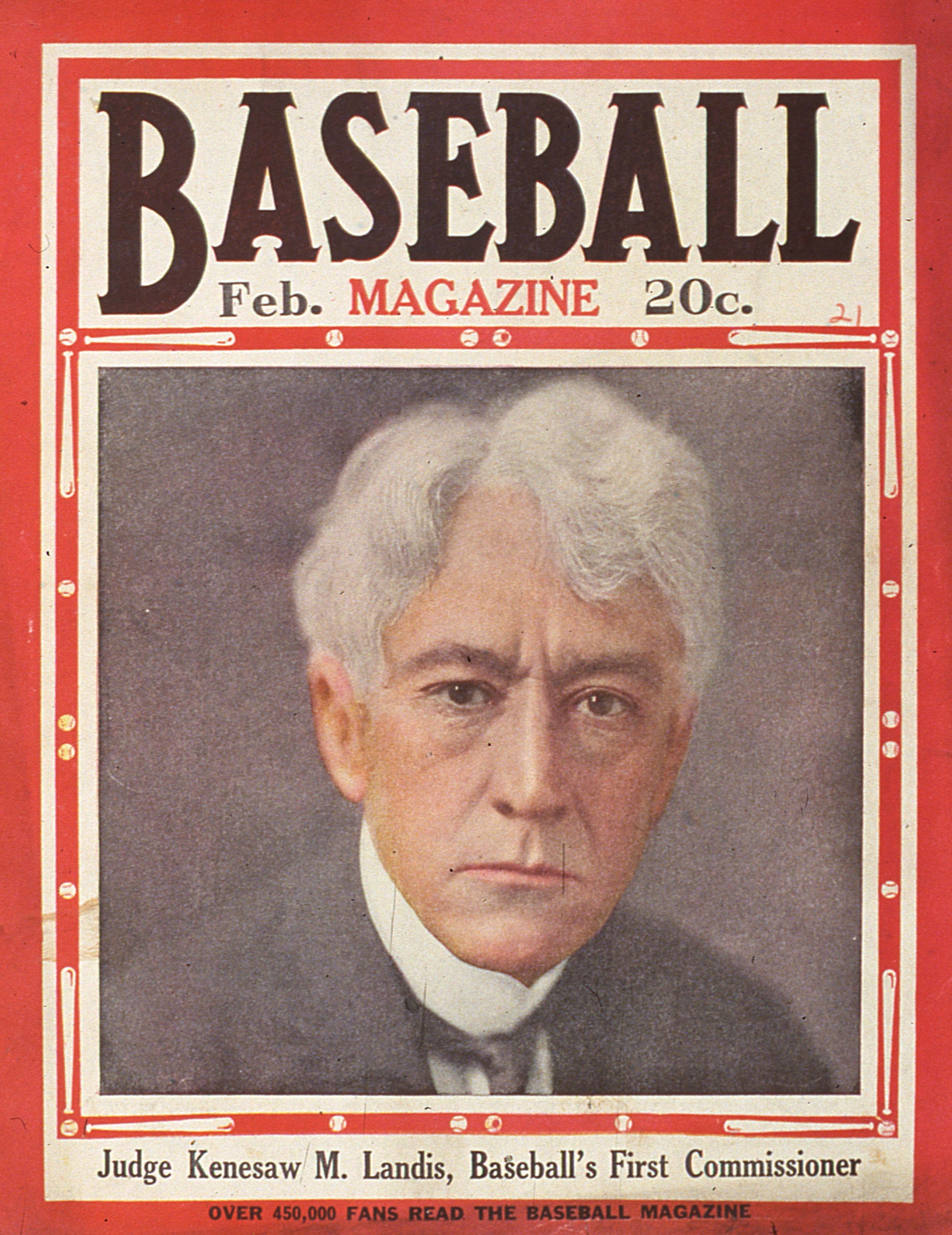

Ongoing conflicts among major-league baseball’s owners and the 1919 World Series game-fixing scandal led to the bringing in of an outsider to take charge of the game’s management, with the appointment of Kenesaw Mountain Landis as the game’s first “Commissioner of Baseball,” a position of enormous power that was officially executed on January 12, 1921.

— Sharon Hamilton and Steve Steinberg

- Read more: “Baseball’s First Commissioner: The Hiring of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis,” by Daniel R. Levitt

“Hitting plays the most important role in a ball game. There is no getting away from the fact that the baseball public likes to see the ball walloped hard. The home runs are meat for the fans. ‘Babe’ Ruth draws more people than a great pitcher does. It simply illustrates the theory that hitting is the paramount issue of baseball.”

— Walter Johnson, Washington Senators pitcher, 1920