April 27, 1893: Cy Young, Cleveland Spiders beat Pittsburgh in opener after pitching distance change

National League hitting and scoring declined during the early 1890s, with pitchers like Cy Young of the Cleveland Spiders on the rise. To boost offense, the NL adjusted its rules in 1893, most prominently by increasing the distance between batter and pitcher to 60 feet 6 inches. In their first game at the new distance, Young and the Spiders, augmented by trade acquisition Buck Ewing, overcame a shaky start for a season-opening 7-2 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 27 at Exposition Park.1

National League hitting and scoring declined during the early 1890s, with pitchers like Cy Young of the Cleveland Spiders on the rise. To boost offense, the NL adjusted its rules in 1893, most prominently by increasing the distance between batter and pitcher to 60 feet 6 inches. In their first game at the new distance, Young and the Spiders, augmented by trade acquisition Buck Ewing, overcame a shaky start for a season-opening 7-2 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 27 at Exposition Park.1

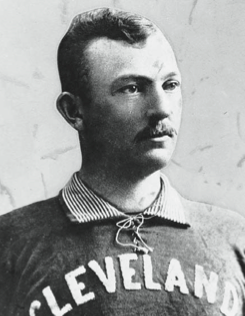

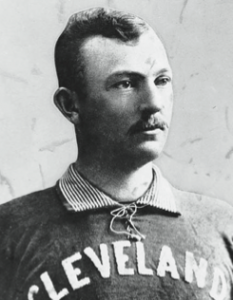

Denton True Young – known as “Cy” since his professional debut in 1890 – emerged as an ace in 1892, pacing the NL in wins (36), ERA (1.93), and shutouts (9). According to historian David Fleitz, the Spiders of the 1890s “cut a swath through the National League, with brawls, fan violence, and umpire abuse regarded as necessary components to wining baseball strategy,” but the spartan Young was an exception to the hooliganism.2

In 1892 Young pitched the Spiders to their first winning record in four NL seasons; Cleveland won the league’s second-half title under a novel “split season” format before getting swept in the championship series by the first-half winners, the Boston Beaneaters. “Young sends terror into the hearts of the timid batsmen when he shoots the ball over home plate with cyclonic force, and his reputation has as much to do with his success in this respect as his real ability,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer asserted.3

But Young was not the only pitcher dominating in 1892.4 The overall NL batting average was down to .245, dropping for the fourth season in a row. The last time offense had been so low, in 1888, baseball had reduced the number of balls for a walk from five to four.5 With scoring dipping once again, discussions of mitigating the impact of hard throwers like Young and Amos Rusie of the New York Giants by extending the pitching distance, set at 55 feet 6 inches since 1887, began at the league meetings in November.6

When the owners reconvened in March 1893, they agreed to require pitchers to start from a white rubber plate 60 feet 6 inches from home.7 They also clarified the balk rule, limiting a pitcher’s movement prior to the pitch.8

Rulebook revisions were not the only changes for Young and the Spiders in 1893. On February 25 Cleveland traded 22-year-old George Davis, a regular member of its lineup at several positions since 1890, to the Giants for veteran William “Buck” Ewing.9

A Giant since 1883 – except for a season in the rival Players’ League – the versatile Ewing was one of baseball’s best players in the 1880s.10 Now 33 years old, however, he had been limited by an arm injury in recent seasons.11 “What on earth the Cleveland club want[s] with Ewing would be hard to tell,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle scoffed, labeling Ewing “almost a candidate for the retired list.”12

But Ewing was in right field when the Spiders traveled to Pittsburgh to open the season. The Pirates had rebounded from their disastrous 1890 campaign, when defections to the Players’ League resulted in a 23-113 record. In 1892 they had their first winning season since joining the NL in 1887.

A large crowd, reported at 7,600, filled Exposition Park on a cool, sunny afternoon.13 “Old men and young scrambled alike to secure places where they could command an unobstructed view of every movement made by the players,” the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette observed.14 Both teams, led by a brass band, paraded there through city streets.

As game time approached, no umpire was present. Finally, “[a]fter the spectators had craned their necks almost out of joint,” Tom Lynch arrived.15 Umpire Lynch gathered the pitchers, Young and Pittsburgh’s Frank Killen, and explained the changes to the balk rule. The season could begin.

Pittsburgh, per baseball’s rules in 1893, elected to bat first, and Young struggled at the outset. Patsy Donovan bunted the game’s second pitch toward third for a single. Young attempted a pickoff, but Lynch – enforcing the rule explained minutes earlier – called a balk, moving Donovan to second. George Van Haltren sacrificed Donovan to third.

Frank Shugart walked and stole second. Mike Smith hit a roller to short; Ed McKean took the out at first while Donovan scored and Shugart advanced to third.

Keeping up the pressure, Jake Beckley walked and took off for second. When catcher Charles Zimmer threw to third, hoping to catch Shugart off the bag, Patsy Tebeau dropped the ball, and Shugart scored for a 2-0 Pittsburgh lead. It took Young 25 minutes to get through the inning.16

After Pittsburgh batted, the 75 Spiders fans who had made the 130-mile trip from Cleveland presented Tebeau with a display of flowers. The arrangement depicted two crossed bats surrounded by a ball, with script reading, “Cleveland B.H.C., Champions of 1893.”17

The Pittsburgh Post described the fans’ gesture as having “a confidence that many took for downright arrogance and a few for open defiance.”18 Tebeau, Spiders player-manager and driving force, raised his cap, bowed several times, and shouted, “It will never do to lose with that!”19

Perhaps inspired by the gift, the Spiders rallied against Killen, a 22-year-old Pittsburgh native, acquired a month earlier in a trade with the Washington Senators.20 Cupid Childs led off with a walk and advanced to second on McKean’s one-out single to left.

Batting for the first time as a Spider, Ewing singled, driving in Childs with Cleveland’s first run. When catcher Connie Mack attempted to catch McKean advancing to third, the throw went wild, and McKean scored the tying run.

The play left Ewing on second, and he stole third. Jake Virtue then grounded to Lou Bierbauer at second; Ewing beat Bierbauer’s throw home for a 3-2 Cleveland advantage.

After Killen turned Jimmy McAleer’s bunt into a force at second, Tebeau hit a grounder to third, but Denny Lyons bobbled it and threw it away; Tebeau took second and McAleer moved to third. Zimmer drove in McAleer with a single. By the time the inning was over, nine Spiders had batted and Cleveland held a 4-2 lead.

The Spiders followed their first-inning surge by pulling away with runs in the third, fourth, and fifth innings. They manufactured a run in the third when Ewing singled, moved to second on Virtue’s sacrifice, stole third, and came home on another wild throw by Mack.

In the fourth, Childs lined Killen’s pitch to center. Van Haltren misjudged the ball, and it rolled all the way to the bleachers. Childs circled the bases for a home run, giving the Spiders a 6-2 lead.

Ewing scored the game’s final run in the fifth, when he singled to center, stole second, moved to third on Virtue’s sacrifice, and scored on McAleer’s single. For the afternoon, Ewing contributed three hits, three runs, three steals, and a catch of “a difficult chance which took him into a foot or more of water and mud” in right.21

“Ewing, whom the New York reporters have written down as a back number, was the star performer of the day,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported.22 “He knocked the ball at will, ran bases with excellent judgment and much daring and gave other evidences that he is still one of the best players of the league.”23

Young was in control after the rough opening, holding the Pirates scoreless over the final eight innings, with only two runners getting as far as third. He struck out just two batters, but Pittsburgh walked only once after the first inning. The Spiders’ infield backed Young with a near flawless performance, with one error and 13 assists. The Cleveland Plain Dealer observed, “Cleveland made but one error, and considering the condition of the ground this is remarkable.”24

“The game went to Cleveland without a murmur from the crowd, as it was won on its merits,” the Pittsburg Press noted.25

As the 1893 season played out, the rule changes produced significantly more offense. Young’s numbers reflected the trend; his 3.36 ERA was nearly a run and a half higher than 1892’s, mirroring the league’s overall rise, but he adapted enough to finish third in the league in ERA.26

Ewing had a strong season in 1893, but his career wound down soon afterward. Meanwhile, Davis had an outstanding nine-season tenure with the Giants, eventually joining Ewing in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Cleveland finished 1893 in third, 12½ games behind the Beaneaters.27 The Spiders fielded winning teams through 1898, then collapsed with a 20-134 record in 1899 after owner Frank Robison purchased the St. Louis Perfectos, one of several clubs struggling financially, and transferred most of Cleveland’s best players there.28 By 1900 Young was winning 20 games in St. Louis, Ewing was managing the Giants, and Cleveland’s NL team had folded.

But on Opening Day 1893 that dismal end was far away. The moment belonged to Young, Ewing, and their traveling fans.

“A good many of the Cleveland cranks can buy summer suits with the money they won on the game,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer concluded.29

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Bruce Slutsky and copyedited by Len Levin. SABR members Vince Guerrieri, Andrew Terrick, and John Thorn provided helpful research assistance; Kurt Blumenau had insightful comments on an earlier draft of the article.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes below, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information. He also relied on coverage from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, Pittsburgh Post, and Pittsburg Press newspapers.

Notes

1 Between 1890 and 1911, United States government regulations required that the names of all cities and towns ending with “burgh” be spelled without the final “h.” Accordingly, the city of Pittsburgh was known as “Pittsburg” during this period. “Pittsburgh with the ‘H’ Please: Geographic Board Reconsiders Dropping Final Letter,” Pittsburgh Post, July 22, 1911: 1. This article uses the current “Pittsburgh” spelling, except in reference to publication titles or direct quotations using “Pittsburg.”

2 David L. Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders: Fighting to the Bottom of Baseball, 1887-1899 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 2-3.

3 “The First Game: Cleveland and Pittsburg Teams Come Together Today,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 27, 1893: 5

4 Anthony Castrovince, “How Baseball Settled on 60 Feet, 6 Inches: A Lot of Experimentation and a Lot of Strikeouts Along the Way,” MLB.com, August 9, 2021, https://www.mlb.com/news/why-is-the-mound-60-ft-6-inches-away.

5 After the change, league batting average had increased from .239 in 1888 to .266 in 1889.

6 Sam Crane, “New Baseball Rules: What the Pitcher’s Position and Bunt Hit Mean to the National Game,” Buffalo Courier, December 5, 1892: 8. Historically, extensions of pitching distance had resulted in increased offense. When the NL adopted a 50-foot distance in 1881, replacing the previous 45-foot span, the league batting average increased from .245 to .260.

7 “Base-Ball Rules Changed: Pitcher Put Back Five Feet – National League Meeting,” Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, March 8, 1893: 7.

8 “Base-Ball Rules Changed.”

9 “Davis for Buck: Cleveland Secures the Famous Ball Player,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 26, 1893: 6; “A Fine Player for Gotham: George Davis, the Crack Cleveland Fielder, Signs with New York,” New York Sun, February 26, 1893: 8.

10 “[Ewing] was regarded by many people as the best player in nineteenth century baseball,” historian Bill James wrote. Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, (New York: The Free Press: 2001), 379.

11 “Davis for Buck.” David Nemec’s SABR BioProject biography contains a good discussion of Ewing’s arm injury during the early 1890s, including disputes over the circumstances and extent of the injury.

12 “Signing the Players: Brooklyn Ball Tossers Coming Into the Fold,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 28, 1893: 5. As David Fleitz discussed in his book on the Spiders, Cleveland’s motivation for the trade was to repay the Giants for supporting a league policy for the even split of gate receipts between home and road teams. After New York finished eighth in the NL in 1892, as Fleitz wrote, “[t]he other magnates, including [Cleveland owner] Frank Robison, knew that a strong New York franchise was good for the league as a whole, so Robison, to repay the Giants for their support in the gate receipt matter several years before, offered to send a star player to New York.” Giants player-manager John Montgomery Ward was initially interested in Patsy Tebeau, to, as the New York Sun reported, “leave a good field captain in charge of the New York team” if Ward followed through on his plans to retire after the 1894 season. Robison did not want to trade the 28-year-old Tebeau but agreed to trade Davis instead. Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 74-76; “A Fine Player for Gotham.”

13 Two Pittsburgh newspapers, the Pittsburgh Post and Pittsburg Press, had the attendance as 7,600; a third, the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, reported 7,950 spectators.

14 “The Record Broken: Pittsburghs Suffer Defeat at the Hands of the Spiders,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, April 28, 1893: 6.

15 “They Are Rattled: Pittsburgh Players Harmoniously Confused by Big, Boisterous Crowd,” Pittsburgh Post, April 28, 1893: 6. Lynch later served as president of the National League from 1910 through 1912.

16 “Victory Placed Its First Laurels on Cleveland’s Club: Pittsburg Downed 7 to 2 in the Opening Game,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 28, 1893: 3.

17 “They Are Rattled.”

18 “They Are Rattled.”

19 “They Are Rattled.”

20 Pittsburgh sent catcher Duke Farrell to Washington for the left-handed Killen, who went on to lead the NL in wins in 1893 (36) and 1896 (30). “Pittsburgh Gets Killen: Farrell Traded to Washington for the Pitcher,” Pittsburgh Post, May 22, 1893: 6.

21 “They Are Rattled.”

22 “Victory Placed Its First Laurels on Cleveland’s Club.”

23 “Victory Placed Its First Laurels on Cleveland’s Club.”

24 “Victory Placed Its First Laurels on Cleveland’s Club.”

25 “Sporting,” Pittsburg Press, April 28, 1893: 5.

26 Young led the NL in 1893 in the twenty-first-century century metric of Fielding Independent Pitching, which measures pitcher effectiveness by strikeouts, walks, hit batters, and home runs allowed. Joe Posnanski, The Baseball 100 (New York: Avid Reader, 2021), 495.

27 Pittsburgh finished the season in second place, five games behind Boston.

28 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 163-180.

29 “Victory Placed Its First Laurels on Cleveland’s Club.”

Additional Stats

Cleveland Spiders 7

Pittsburgh Pirates 2

Exposition Park

Pittsburgh, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.