April 3, 1982: Twins shut out Phillies in exhibition to open the Metrodome

It was a “perfect” Saturday night for baseball: 19 degrees and sleeting, winds at 30 miles per hour, gusting to 45.

It was a “perfect” Saturday night for baseball: 19 degrees and sleeting, winds at 30 miles per hour, gusting to 45.

On the eve of the 1982 season, the Minnesota Twins and Philadelphia Phillies were set for an exhibition game to open the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome on the edge of downtown Minneapolis. “Dome” was the operative word in the stadium’s name, allowing for baseball in a climate-controlled 71 degrees that night with no wind, not even enough to disperse the smell of marijuana from fans—not yet accustomed to the concept of “smoke-free” at a baseball game1—in the front rows beyond the first-base dugout.

The Metrodome was functional but bland. Nevertheless, the more than 25,000 spectators who braved the lingering winter weather were greeted on the giant message board with, “Welcome to the Fabulous Metrodome.” Over time, the scoreboard’s capability for baseball information, replays, and highlights—in addition to advertisements and forgettable dot-matrixed flotsam—increased, but it was a technological step forward from the “Twins-O-Gram” at Metropolitan Stadium, which was limited to a handful of characters for noting the distance of a home run or greeting groups in attendance.

The Twins had played their first 21 seasons in Minnesota at “The Met,” a ballpark carved into a cornfield in a southern suburb and used by the minor-league Minneapolis Millers until the area could lure a major-league team. Big-time football also arrived with the National Football League’s Minnesota Vikings, who shared Met Stadium although they were clearly the less favored tenant. As the Vikings achieved success, reaching the Super Bowl four times between the 1969 and 1976 seasons, while the Twins nosedived after an American League pennant in 1965 and AL West titles in 1969 and 1970, the Vikings lobbied for a new ballpark of their own.

In 1977 the Minnesota legislature passed a no-site stadium bill, mandating a new stadium—or stadiums. The type and location were left to a stadium commission, which considered alternatives, both open-air and covered, including sites in Minneapolis and the suburbs, and the expansion of Met Stadium for baseball with a football-only stadium adjacent to it.

The December 1978 announcement of the commission’s choice, a multipurpose covered stadium in Minneapolis, pleased some and enormously irritated others. Controversy, lawsuits, and a huge amount of public bickering took place over the next two years as earthwork on the site and then construction proceeded.

Finally, the Metrodome, named after the former Minneapolis mayor, United States senator, and vice president who had died in January 1978,2 was ready for occupancy, and fans swarmed in—out of a love or baseball or just outright curiosity—for the first event, on April 3, three days before the dome’s first scheduled regular-season game.

Both teams flew in after Friday games in Florida—the Phillies from their base in Clearwater, the Twins from Dunedin, where they had played the Toronto Blue Jays. Philadelphia slugger Mike Schmidt had a negative assessment of the Metrodome when he learned of its asymmetry of longer distances to left field than right. “I’m totally against that from the outset,” the reigning two-time National League MVP said. “That’s ridiculous.”3

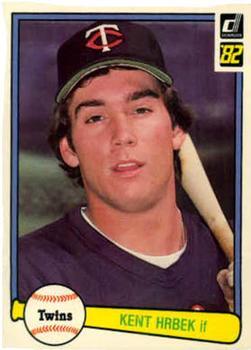

Kent Hrbek, a lefty swinger and Minnesota native about to start his first full season in the majors with the Twins, may have liked the set-up better. Twins coach Jim Lemon said, “Hrbek must know an awful lot of politicians to get a fence built like that.”4 The distance down the line in right was 327 feet and 367 in right-center (compared with 343 and 385 to left and left-center, respectively). The fences originally were only seven feet high around the outfield, but the fence in right was eventually made higher.5

Minnesota manager Billy Gardner had other things on his mind as he strolled through the ballpark for the first time on Saturday afternoon, a wad of tobacco in his cheek. “I’m looking for a place to spit.”6

The umpires also found some shortcomings. Gerry Davis, who made his debut in the majors in 1982, worked with Durwood Merrill (who had the plate in the first game) and Dutch Rennert. Davis later recalled that the crew arrived and found there was no umpire room. “No one had thought about it,” he said, adding that they changed clothes in some kind of a closet.7

Ready or not, the Metrodome debuted at 7:35 that night as Minnesota’s Pete Redfern fired a strike to Iván de Jesús, newly acquired in a January 1982 trade with the Chicago Cubs.8 Despite getting ahead 0-and-2, Redfern walked de Jesus, bringing up Pete Rose, who grounded Redfern’s fourth pitch up the middle for a single.9 Redfern had dug a hole for himself but got out of it and followed with a scoreless second, despite two more baserunners, before being relieved by Darrell Jackson to start the third.

Mike Krukow—whom the Phillies had obtained in another winter 1981-82 trade with the Cubs, separate from the de Jesús deal—started for Philadelphia and got through the first three innings without too much trouble. In the last of the fourth, after Dave Engle flied out on the first pitch, Krukow walked Roy Smalley on four pitches.

Hrbek was up next. A graduate of Kennedy High School in Bloomington who had grown up near Metropolitan Stadium, Hrbek had made the jump from Class A to the majors the previous August and, in Yankee Stadium, had homered in his first game. He had been hot in spring training, hitting seven home runs while in Florida.

Now inside, Hrbek christened the new ballpark with a home run off the facing of the second deck in right, giving the Twins a 2-0 lead.

The Twins got to Krukow again in the sixth, scoring one run on singles by Engle, Smalley, and Hrbek and another on a sacrifice fly by Gary Gaetti.10 Ron Reed finished the inning and pitched the seventh before Sparky Lyle took over in the eighth.

Lyle got the first two batters before going to a full count on Hrbek, who hit the next pitch over the fence and just to the right of the 408-foot marker in straightaway center for his second homer of the game and ninth of the preseason, tying Harmon Killebrew for the most Twins home runs in spring training. (Killebrew had hit nine in 1967.) The distance of Hrbek’s homers caused Jim Lemon to revise his pregame quip: “He didn’t need any politicians for those.”11

The Phillies didn’t mount any threats in the middle innings as Jackson allowed only a sixth inning walk to de Jesús, which was followed by Rose grounding into a double play. Bobby Castillo, who had pitched for the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1981 World Series, then joined the Twins in an offseason deal, handled the final three innings for the Twins. He gave up a two-out double to Dick Davis in the eighth and singles by Rose and Matthews to start the ninth. Len Matuszek then forced Rose at second, George Vukovich struck out, and pinch-hitter Greg Gross grounded out to second baseman Rob Wilfong to end it.

Those who attended the initial game—played in a snappy 1 hour 57 minutes—seemed satisfied. Of course, not every baseball game was played when it was 19 degrees outside. The drawbacks of the dome, as everyone knew, would become apparent on the many nice days and evenings when the Twins played. And for the first season, fans suffered through heat and humidity inside. Ductwork for air-conditioning was installed, but the stadium commission decided to see if it was needed. It was and was installed the following season.

The dark roof caused many fly balls to be lost by outfielders,12 and the spongy turf created high bounces. The problems were eventually lessened somewhat by lights directed to the roof and different turf. But the sterile and antiseptic atmosphere resisted attempts at amelioration, and some would say such efforts only made it worse. Nevertheless, the Metrodome provided many memorable events—in a variety of sports and other activities—including World Series in 1987 and 1991. In addition, a generation of fans had the Metrodome as their introduction to baseball and cherished their memories of it in the same way as older fans who had grown up with Metropolitan Stadium.

The Twins began lobbying for a new stadium in the 1990s and finally got what they wanted years later. The final game in the Metrodome was a playoff loss to the New York Yankees in October 2009. When the Twins next played at home, it was at Target Field at the other end of downtown Minnesota—under sunshine, rain, hail, and sometimes snow.

Epilogue

Rose, who had played in the 1965 All-Star Game in at Met Stadium, returned for the 1985 All-Star Game at the Metrodome. Spending his entire 24-season career in the National League, prior to interleague play, he never played in a regular-season game in the state.

Nor did Schmidt. Vocal in his opinion of the Metrodome’s dimensions, he missed both games the Phillies played there after fouling a pitch off his foot in their final Florida exhibition game.13 Schmidt was not selected for the 1985 All-Star Game and never played in Minnesota as a professional. As a collegiate player with Ohio University, however, Schmidt did homer against the Minnesota Gophers in the 1969 NCAA District 4 playoffs at Bierman Field in Minneapolis.

The weather was better, but not by much, three nights later when the first regular-season game was played in the Metrodome. There was no precipitation, but temperatures dipped below 30 degrees outside as Seattle beat Minnesota 11-7 in the first official game.

Minnesota briefly became the envy of other teams, which had their games postponed by cold and snow in cities to the east. On Tuesday, April 6, six openers were postponed—in Chicago (White Sox), Detroit, Milwaukee, New York (Yankees), Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh—and games for the following days were called off. The White Sox and Blue Jays, who were snowed out in Detroit, arranged to play practice games in the Metrodome before and after the Twins games on Wednesday and Thursday. Over time, the Metrodome became the round-the-clock home for many college, high-school, and other amateur teams for early-season baseball. It was one of the city’s most functional and flexible buildings, regardless of what it may have lacked for charm and amenities.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Laura Peebles and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

Scorebook and memories of the author, who was not one of the dope-smoking fans but was close enough to them to be aware of their antics.

The author also relied on information from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Domed stadiums were the first to prohibit smoking in the seating areas. The Metrodome allowed smoking in the concourses, eventually limited it to designated areas in the concourses, and finally eliminated smoking altogether in the ballpark. The Oakland Athletics, in 1991, were the first team with an open-air stadium to prohibit smoking in any of the seating areas. By 1996, all teams except Milwaukee had adopted similar policies. In 1995 the author and his not-yet wife, Brenda Himrich, conducted a survey of all major-league teams regarding their smoking policies. The survey is at https://milkeespress.com/mlbsmokingpolicies1995.pdf.

2 In 1977 the stadium commission announced that the new stadium would be named after Humphrey. Seen as a ploy to use the name of a beloved Minnesotan who was dying of cancer as a way to head off opposition to the stadium, it didn’t work. The stadium was built but not without a lot of controversy. Some people advocated for the stadium to be named after another beloved personality: Halsey Hall, a longtime sportswriter/announcer and colorful character. Hall died in late 1977, after the commission had decided to use Humphrey as the stadium’s namesake. In 1985 the SABR group in Minnesota formally organized itself into a chapter and named it after Halsey Hall.

3 Jay Weiner, “Schmidt Ready to Show Dome Who’s Boss,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 3, 1982: 1D.

4 Jay Weiner, “Twins Open Dome with 5-0 Win,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 4, 1982: 1C.

5 Plexiglass was added to the top of the left-field fence for many years, not so much to deter home runs as to keep balls in play after they bounced off the spongy turf.

6 Weiner, “Twins Open Dome with 5-0 Win.”

7 Conversation with Gerry Davis at the Society for American Baseball Research convention in San Diego, June 29, 2019.

8 The Cubs obtained shortstop Larry Bowa and 22-year-old infielder Ryne Sandberg in the trade.

9 In the lore of new stadiums, the firsts sometimes have to be qualified by whether they occurred in an exhibition contest or a regular-season game. Since the first hit was by a player who already had more than 3,000 of them in his career and who seemed destined for the Hall of Fame, Pete Rose is the usual answer to the question of who got the first hit in the Metrodome. The first hit in a regular-season game came three nights later, a first-inning home run by Minnesota’s Dave Engle.

10 Gaetti had been one of three Twins to debut in 1981 with a home run in his first game. Hrbek and catcher Tim Laudner were the others. Gaetti’s first home run came in his first plate appearance.

11 Weiner, “Twins Open Dome with 5-0 Win.”

12 One ball didn’t even come down. On May 4, 1984, Dave Kingman of Oakland hit a popup that went through a vent hole and was stuck in the roof. Kingman was awarded a double.

13 The Phillies and Twins played again the next afternoon with the Phillies winning 11-8.

Additional Stats

Minnesota Twins 5

Philadelphia Phillies 0

Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome

Minneapolis, MN

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.