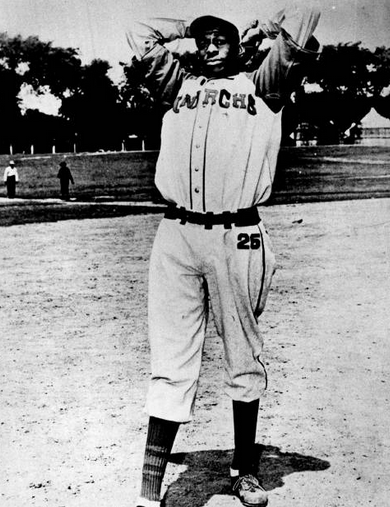

August 26, 1934: The Hottest Show in Town: Satchel Paige mows ’em down in Negro Leagues all-star game

The summer of 1934 was one of the hottest on record in Chicago. Although the heat was nothing out of the ordinary for Negro League All-Stars like Alex Radcliff and Satchel Paige, who both grew up in Mobile, Alabama, it was still fortunate for them, and for the fans attending the matchup of the best that Black baseball had to offer that season, that the temperatures cooled slightly from the record-setting 105 degrees of July 24 and the 100 degrees of August 8. August 26 was, as one observer put it, “one of those perfect baseball days. Not a cloud in the sky to mar the perfect azure-blue of the heavens.”1

What the weather may have lacked in heat, the annual East-West All-Star Game, played at Comiskey Park, made up for. It was a hotly contested game.

Although it was an exhibition, both teams wanted nothing more than to win. The 1934 edition of the classic turned out to be a pitchers’ duel if ever there was one. The East team won, 1-0, on a run that crossed the plate in the next-to-last inning.

Until then, the West pitching had been excellent. Ted Trent started and allowed two hits while striking out three batters. He was helped by top-notch defense, with Sammy Hughes and Willie Wells making great plays in the infield. Chet Brewer pitched the middle three innings, yielding two hits and striking out a pair of batters including Oscar Charleston, who struck out twice in the game. Willie Foster entered the game in the seventh inning and allowed a two-out single to Chester Williams, who was stranded when Paige grounded out to shortstop.

Cool Papa Bell, one of six Pittsburgh Crawfords to start the game, scored the game’s only run, in the top half of the eighth inning. Bell was known throughout the Negro Leagues as an excellent baserunner. According to Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Bell was “so fast, he’d run out of sight.”2 (Double Duty was the brother of Alex Radcliff, who started at third base for the West team.)3

Bell was an on-base artist extraordinaire, who knew how to work pitch counts when necessary to reach first base. His pesky ways got only more annoying for opposing pitchers, catchers, and managers once he got on base, and that was most certainly the case in the eighth inning of this game. Facing hometown pitcher Foster of the Chicago American Giants, Bell worked the count to 3-and-1 and then took first on a base on balls. It was the only walk Foster issued in three innings of mound work.

Pittsburgh Crawfords catcher Bill Perkins was up next, pinch-hitting for Jimmie Crutchfield, was up next. Bell used his legendary speed to steal second base on a swinging strikeout by Perkins. Pittsburgh first baseman Oscar Charleston then hit a soft liner to first baseman Mule Suttles for the second out. Philadelphia Stars third baseman Jud Wilson, “one of the game’s most dangerous hitters,” was down in the count 0-and-2 when he “hit a looping single over second. It was a hit, but [shortstop] Willie Wells and [second baseman Sammy] Hughes both went for it.”4 With two outs, Bell had been off on contact. Both Wells and Hughes “broke the ball down, but it rolled a few feet away.”5

The New York Amsterdam News described the hit as a “fast grounder through the pitcher’s box out into short center field.”6 As both middle infielders went for the ball, “Wells got in front of it” but “Hughes crashed into him and Bell scampered about third to score.”7 Josh Gibson was up next and he singled, but the throw from right fielder Sam Bankhead was relayed home and caught Wilson as he tried to score a second run.

In the bottom of the ninth, Paige stuck out Turkey Stearnes and, after a single by Suttles, the game ended on a double play as Williams grabbed a liner by Red Parnell and doubled off pinch-runner Malvin Powell at first base.

Paige, who had entered the game with none out in the sixth inning and a runner on second base, struck out five batters. He prevented the West from scoring in the four innings he pitched and was the pitcher of record when the winning run was scored. As the third and final pitcher (following starter Ted Trent and Chet Brewer) used by West manager Dave Malarcher, Foster took the loss in the contest.8

Wilson’s Philadelphia Stars went on to win the 1934 Negro National League II championship by defeating the Chicago American Giants in a playoff series; it was the only championship in franchise history. For the moment, however, the big news was that Wilson had played the role of hero in a game that had included stars like Wells, Charleston, Stearnes, and Josh Gibson. Wilson had been second in vote-getting among East position players, and he was such a strong hitter that East manager Dick Lundy had batted him in the cleanup spot for the East. If anyone was likely to drive in the only run in a 1-0 game, Wilson was the one who was the most probable. As it turned out, he had his opportunity and made the most of it.

In addition to Wilson, credit for the East’s victory was also due to the sterling efforts of the three pitchers used by Lundy (who doubled as the starting shortstop). Philadelphia’s Slim Jones was the starter. His day got off to an inauspicious start as he walked the leadoff hitter, Wells, and then balked him to second. Wells was thrown out trying to steal third, as Alex Radcliff struck out.9 Jones struck out Stearnes to end the inning. He pitched two more innings in which he allowed just one more baserunner. He struck out four West All-Stars in his three innings on the hill.

However, there were some anxious moments in the second inning. After Suttles opened the inning with a single, Parnell reached base on an error when second baseman Williams’s throw was mishandled at first base by Charleston. After Bankhead struck out, the runners advanced to second and third on a wild pitch. Suttles tried to score on Larry Brown’s groundball to third base, but Jud Wilson’s timely throw home to catcher Gibson prevented the run from scoring. Hughes grounded out to Wilson to end the threat.

After Jones retired the side in order in the third inning, he was relieved by Pittsburgh Crawfords right-hander Harry “Tin Can” Kincannon. The curveball artist was not as sharp for the East squad as his predecessor or his successor. In two innings of relief, he gave up four hits but continued to keep the West team with a zero in the run column as he bridged the gap to the most dominant Negro Leagues pitcher of the era, Leroy “Satchel” Paige. Mule Suttles was thrown out at home after tripling in the fourth inning. Right fielder Crutchfield grabbed a fly ball hit by Parnell and executed a perfect throw to end the inning.

Pitching in this contest against the best Negro Leagues competition he could face, Paige, who entered the game with none out and a runner on second in the sixth inning, powered through the West lineup with his blazing, heavy fastball for four shutout innings to record the win for the East squad. He used his fastball, curveball, changeup, and even occasional knuckleball to confuse West hitters and keep them off balance.

According to both Bell and Double Duty Radcliffe, Paige threw his fastball as fast as anyone in the Negro Leagues. Radcliffe had caught him when they were teammates with the Crawfords in 1932. He recalled a doubleheader in New York in which he caught Paige in game one, and then took the mound himself in the second game. Both pitched shutouts.

Asked if Paige threw hard, Radcliffe said, “When I had to catch Satchel, I’d go to the store to get a wrap.” He asserted that “Nobody who ever lived threw harder than Satchel. Closest was Bob Gibson. Satchel could throw so hard, looked like the ball disappeared.”10

In addition to the players who were key figures in the East’s victory, the 1934 East-West All-Star Game featured much of the best talent the Negro Leagues ever produced. In the midst of that talent, some individual standouts, who did not necessarily affect the final outcome of the game, were Pittsburgh second baseman Chester Williams for the East and Chicago first baseman Mule Suttles for the West, who collected three hits apiece.

For the 30,000 fans in attendance, the second annual East-West Game did not disappoint.11 They got every bit of their money’s worth as they watched the East avenge an 11-7 loss in the inaugural East-West All-Star Game from the year before. In the Pittsburgh Courier’s September 1 edition, columnist William G. Nunn raved, “Today’s game was more than a masterpiece! It was more than a classic! It was really and truly a diamond epic!”12

Sources

This article was amended by Alan Cohen and Bill Nowlin in 2023 and fact-checked by Carl Riechers. Thanks to Alan Cohen and Tom Thress of Retrosheet. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the authors consulted Retrosheet.org and the following:

“East-West All Star Game: Summaries,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/East-West%20All%20Star%20Game%20Summaries%202019-10.pdf

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-1962, Expanded Version (Kansas City: Noir Tech Research, 2020), 40-59.

Mandel, Ken, MLB.com. Slim Pitcher: Jones Dominated Negro League Baseball for a Short Time. mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_negro_leagues_profile.jsp?player=jones_stuart.

Monroe, Al. “East Beats West in 1-0 Thriller,” Chicago Defender, September 1, 1934: 16.

Thorn, John, Black Ball, Part 2. “Our Game,” ourgame.mlblogs.com/black-ball-part-2-1dcade51cdf6.

Washington, Chester. “Says Ches: 25,000 Thrilled at East-West Spectacle,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 1, 1934: A5.

“Bat Boys Responsible for East Team’s 1-0 Victory,” Chicago Defender, September 1, 1934: 15.

“East All-Star Team Wins, 1-0, Before 25,000,” Chicago Tribune, August 27, 1934: 21.

Notes

1 William G. Nunn, “As ‘Speedball’ Satchell [sic] Paige Ambled into the East-West Game and Simply Stole the Show,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 1, 1934: A4.

2 Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, interviewed by Fay Vincent, Society for American Baseball Research, July 5, 2002. https://sabr.org/interview/ted-double-duty-radcliffe-2002/.

3 Alex Radcliff’s surname was sometimes rendered as Radcliffe.

4 Nunn.

5 Nunn.

6 “East Defeats West in Game at Chicago,” New York Amsterdam News, September 1, 1934: 10.

7 Dan Burley (Associated Negro Press), “East Shuts Out West in Classic Title, 1-0,” Atlanta Daily World, September 2, 1934: 5.

8 For a box score of the game, see Al Monroe, “East Beats West in 1-0 Thriller,” Chicago Defender, September 1, 1934: 16.

9 Julius J. Adams, “Adams Gives a Detailed Story of East’s Victory,” Chicago Defender, September 1, 1934: 17.

10 Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe interview.

11 Estimates of crowd size ranged from 20,000 to 30,000. Nunn wrote that more than 4,000 of those in attendance were White.

12 Nunn.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.