July 10, 1880: Cleveland’s Jim McCormick, Fred Dunlap end Chicago’s 21-game winning streak

The 1880 Chicago White Stockings were unstoppable, winning 67 against only 17 losses. Their .798 winning percentage has never been equaled by another National League team.1

The 1880 Chicago White Stockings were unstoppable, winning 67 against only 17 losses. Their .798 winning percentage has never been equaled by another National League team.1

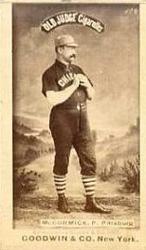

During that dominant season, no pitcher gave Chicago more trouble than Jim McCormick. A first-year captain of the Cleveland Blues,2 McCormick defeated the White Sox four times, including twice by shutout, the only times all season that the eventual NL champions were “Chicagoed.”3

McCormick’s first whitewashing, won on a game-ending ninth-inning home run by Fred Dunlap on July 10, also extinguished Chicago’s league-record winning streak.

Possessing a level of maturity that belied his age, the 23-year-old McCormick was elected captain prior to the 1880 season, despite losing a league-high 40 games the year before. The Cleveland Leader called McCormick “an old and experienced player,” who possessed good judgment and “a clear, cool head.” The Leader pointed out that “[h]is position as pitcher places him in admirable position to watch every point in the contest, without necessarily interfering with the effectiveness of his delivery.”4 Captaining certainly didn’t diminish McCormick’s stamina; he pitched every inning of the team’s first 31 games.

The Blues were 20-16 and in third place when they welcomed the 35-3 first-place White Stockings to the Forest City on July 10 for the opener of a three-game series. On the first stop of a five-city, 15-game Eastern road trip, Chicago had won 21 straight games, the longest such streak during the NL’s first five seasons. In that time, only the Boston nine of 1877 had strung together as many as a dozen consecutive victories.

The losing pitcher in each of the Blues’ three previous meetings with the Whites, the Scottish-born McCormick was looking for his 20th win of the season against 15 defeats.5 One of those losses was a 1-0 squeaker to the Worcester Ruby Legs in which Lee Richmond crafted the first perfect game in major-league history. Accused by the Chicago Tribune, a week earlier of “tiring out,”6 McCormick was pitching on three days of rest, as much as he’d enjoyed all season.7 His batterymate, Doc Kennedy, was also coming off a three-day hiatus, which may have been intended to help a lacerated eyelid heal, an injury he suffered a week earlier while batting.8

Opposing McCormick was second-year hurler Fred Goldsmith. Goldsmith and diminutive 20-year-old rookie Larry Corcoran were on their way to forming the major leagues’ first true pitching rotation.9 A change (relief) pitcher for the Troy Trojans the year before, Goldsmith was having a banner year, thanks in large part to his mastery of the curveball.10 Sporting a gaudy 16-1 record, Goldsmith had won his last nine starts,11 and, like McCormick, had the luxury of pitching on three days’ rest.

Threatening skies greeted the 1,300 to 1,600 spectators who made their way into Cleveland’s National League Park for the Saturday contest.12 Chicago captain Cap Anson used a lineup that differed from the stacked version he typically rolled out. Corcoran, getting a day off from pitching, was playing center field instead of eventual batting champ George Gore.13

The defending champions were first to bat, with Abner Dalrymple, “the wood-clopper of the West,” leading off.14 McCormick retired the season’s hits leader en route to a one-two-three inning. Goldsmith set the Blues down in order in the first as well, starting with Dunlap, Cleveland’s 21-year-old rookie second baseman.

A leadoff hitter with surprising power, Dunlap came into the game with 21 extra-base hits and a slugging percentage of .556,15 a level high enough to lead the league had he sustained it all season. A sure-handed infielder who umpired a major-league game before ever playing in one,16 he’d landed a contract with the Blues for the 1880 season that reportedly paid him $1,60017 – $600 more than incumbent second baseman Jack Glasscock, who was shifted to shortstop to make room for Dunlap.

Neither side mustered any offense in the second inning, with “a marvelous stop” by Glasscock on a hot shot up the middle by Chicago’s Tom Burns highlighted by the Chicago Tribune as the defensive play of the game.18 In the Cleveland Leader description of that play, Glasscock was referred to as “Honest John,” a nickname given him a year earlier for a trait he apparently held in common with the lead character in a popular play.19

In the top of the third, Blues third baseman Frank Hankinson dropped a one-out pop fly from Silver Flint “like a red hot iron,” giving Chicago the first baserunner of the game. Flint reached second on the play, following an errant (and likely ill-advised) throw by Kennedy.20 Unflustered, McCormick retired the next two batters to keep Chicago from scoring. In the next inning, Chicago’s Ed Williamson singled for the game’s first hit but McCormick picked him off.21

Cleveland threatened to score in its half of the fourth after Dunlap led off with a single to left. Breaking for second on what was either a straight steal or a passed ball, Dunlap kept running when catcher Flint’s throw to second sailed into center field, but Corcoran gunned him down at third.22 The final out of the inning came on a foul bound to Flint, a play that two years later would no longer be an out.

Chicago put another runner in scoring position in the sixth when light-hitting Joe Quest singled with one out and stole second, but he went no farther. In Cleveland’s next turn at bat, a two-out error, either on a wild throw from Burns (according to the Cleveland Leader) or on a missed catch by Anson at first (according to the Chicago Tribune), allowed Glasscock to reach first. He advanced to second on a wild pitch or passed ball but died there when Dunlap made the third out.

Poised to break through in the seventh, the Blues again came up short. A leadoff single, force out, and passed ball put Pete Hotaling on second with one out. Hotaling, the Cleveland center fielder better known to history as maybe the first professional catcher to wear a mask, reached third when 22-year-old rookie Ned Hanlon, the Cleveland left fielder better known to history as “the father of modern baseball” for his innovative methods as manager of the 1890s Baltimore Orioles,23 grounded out to shortstop. With the partisan crowd clamoring for a run, Kennedy popped out to end the inning.

Showing no signs of a weary arm, McCormick overwhelmed Chicago in the eighth. He fanned Corcoran to lead off the inning, and Flint to end it, giving him five punchouts for the game. Goldsmith found success in the bottom of the inning as well, retiring the Blues in order and keeping the game scoreless.

A lack of run support was something McCormick had experienced from time to time, but it was new to Goldsmith. In seven of McCormick’s starts, the Blues had scored one run or less. Only once had Chicago scored as few as two runs in a Goldsmith start.

Anticipating a shutout over the vaunted Whites, the crowd “began to boil” with excitement.24 McCormick got two quick outs to start the inning: a foul tip catch off the bat of Quest and a comebacker from Dalrymple, ending the latter’s 17-game hitting streak.25 Mike “King” Kelly followed with a single up the middle. Building the basestealing prowess that would later inspire cries of “slide, Kelly, slide,” Kelly swiped second, a theft made easy when Dunlap bobbled Kennedy’s throw.26 Briefly silenced by the prospect of Chicago scoring, the crowd “gave one long continuous yell” when Williamson hit an inning-ending groundout.27

The Blues came to bat in the bottom of the ninth with the ballpark “so still that a pin could be heard if dropped.”28 Glasscock, leading off, swung and missed on Goldsmith’s first offering, then took a called strike. Two pitches later, he singled to left, bringing the crowd back to life. Up stepped Dunlap, looking to win the game and end Chicago’s winning streak.

It didn’t take long. The youngster rifled Goldsmith’s next pitch over Corcoran’s head in center field. As the ball rolled to the center-field corner, Dunlap circled the bases for his fourth home run of the season.29 “Cushions, umbrellas, fans and everything imaginable were raised or thrown into the air,” reported the Cleveland Leader, adding that another five minutes passed before the crowd piped down.30 After what the Cleveland Plain Dealer called “as fine a game [as] was ever played here,”31 Chicago’s streak was over.

Goldsmith, who finished the year with the league’s top winning percentage (.875), tasted defeat just once more in the season’s 11 remaining weeks: on September 25 to McCormick and the Blues.32

No NL hurler pitched more often, or for more innings, than McCormick did in 1880. Over 657 innings in 74 starts, all but two of them complete games, he earned a league-high 45 victories.33

Dunlap, whose slugging percentage fell to .429 by the end of his freshman campaign, led the league with 27 doubles, finished second in extra-base hits (40), and second in fielding percentage among second basemen (.911).34

While low-scoring games like this one were favored by baseball purists of that time, the dominance of pitching in 1880 sparked a backlash.35 At the NL’s annual winter meetings in December, owners agreed to increase the distance between pitchers and batters from 45 feet to 50 feet.36 When asked his opinion of the change, McCormick knowingly replied “I have no doubt it will increase the batting.”37

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Bill Marston and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Chris Rainey’s SABR biography of Jim McCormick, David Fleitz’s SABR biography of Fred Goldsmith and Bob LeMoine’s SABR biography of Larry Corcoran. He also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Statscrew.com for pertinent information. In compiling game logs for McCormick and Goldsmith, he relied on game summaries published in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Inter Ocean, Cleveland Leader, Cleveland Plain Dealer, and New York Clipper.

Notes

1 Only the Detroit Wolves of the 1932 East-West League (.839) and the 1884 St. Louis Maroons of the Union Association (.832) compiled higher winning percentages among major-league teams.

2 Both Retrosheet.com and Baseball-Reference.com identify McCormick as being manager of the Cleveland nine in 1880, and the year before; however SABR researcher Chris Rainey determined that McCormick’s role in 1880 was on-field captain.

3 “Chicagoed” was a popular nineteenth-century euphemism for getting shut out. The author has traced what may have been the first use of the term to politics, specifically in reference to a delegate at Chicago’s 1860 Republican National Convention getting his pocket book stolen. “‘Chicagoed,’” Millersburg (Ohio) Holmes County Farmer, May 24, 1860: 3. For more on the origin of the term, see Rich Bogovich and Mark Pestana, “July 23, 1870: The first ‘Chicago’ game,” https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-23-1870-the-first-chicago-game/.

4 “McCormick Appointed Captain,” Cleveland Leader, April 14, 1880: 8.

5 Based on an 1880 Cleveland Blues game log compiled by the author. In compiling that log, the author identified an error in the Retrosheet game database. McCormick’s 6-2 triumph over the Buffalo Bisons identified as taking place on Monday, May 10, actually took place one day later, according to multiple game accounts.

6 “Ball Gossip,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1880: 12.

7 Since Opening Day on May 1, McCormick had twice gone three days without pitching in a game, and never more: June 6 through June 8, and June 29 (the first game that year when someone other than McCormick started for Cleveland) through July 1.

8 “The Game T-Day,” Cleveland Leader, July 10, 1880: 5. Eye injuries were common for nineteenth-century backstops prior to the introduction of catcher’s masks in 1877, but in this case a foul ball off Kennedy’s bat ricocheted into his right eye. According to the Leader’s postgame summary of this contest, Kennedy played with one eye half-closed. “Hankinson’s Hit,” Cleveland Leader, July 3, 1880: 2; “Hip! Hip! Hurray!” Cleveland Leader, July 12, 1880: 12.

9 Frank Vaccaro, “Origins of the Pitching Rotation,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011, https://sabr.org/journal/article/origins-of-the-pitching-rotation/.

10 Goldsmith learned to throw the pitch from Yale University’s Charles “Ham” Avery, the first college hurler to successfully throw one.

11 Based on an 1880 Chicago White Stockings game log compiled by the author.

12 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”; “Cleveland vs. Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1880: 6.

13 This was one of just eight times that Corcoran manned the outfield for Chicago in 1880.

14 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”

15 Based on a game log for Dunlap compiled by the author.

16 “Cincinnatis, 10; Troy, 1,” Boston Globe, September 12, 1879: 4.

17 “Base Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 12, 1880: 1. Dunlap was widely sought across the NL when he signed with Cleveland. He was a hot commodity thanks in part to a glowing profile that appeared in a July 1879 issue of the New York Clipper. “About the Nine for Cleveland Next Year,” Cleveland Leader, October 2, 1879: 8; “Fred Dunlap,” New York Clipper, July 19, 1879: 13.

18 “Cleveland vs. Chicago”; “Team Record,” Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1880: 6.

19 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!” “Dropped,” Buffalo Courier Express, June 25, 1879: 4; “Boston Theatre,” Boston Evening Transcript, January 12, 1880: 1.

20 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”; “Cleveland vs. Chicago.”

21 Batting at the time was Anson, who Chicago Tribune readers learned the next day was the team’s RBI leader. The July 11 Tribune reported, for the very first time, “runs batted home” for each Chicago regular. Anson was listed as having 25, which the accompanying explanation claimed “undoubtedly leads the League.” “Team Record,” Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1880: 6.

22 “Cleveland vs. Chicago.”

23 “Ned Hanlon,” National Baseball Hall of Fame website, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/hanlon-ned, accessed October 22, 2023.

24 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”

25 The hitting streak was the longest of Dalrymple’s career to that point. Based on game logs compiled by the author for his SABR biography of Dalrymple.

26 “Cleveland vs. Chicago.”

27 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”

28 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”

29 Based on a game log for Dunlap compiled by the author. According to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Dunlap’s home run was his fifth of the season, putting him one ahead of Boston’s Charley Jones for the NL lead. Modern databases show Dunlap as having only four home runs for the entire season. Dunlap’s other home runs were on May 15 off Blondie Purcell of the Cincinnati Stars, on June 1 off 20-year-old John Montgomery Ward of the Providence Grays, and on June 4 off Curry Foley of the Boston Red Stockings. No other Cleveland ballplayer homered more than once during the 1880 season. “Base Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1880: 4.

30 “Hip! Hip! Hurray!”

31 “Base Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1880: 4.

32 “Cleveland vs. Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, September 26, 1880: 7.

33 Only Will White of the 1879 Cincinnati Reds (75) and Old Hoss Radbourn of the 1884 Providence Grays (73) completed more games in a single major-league season. McCormick’s innings pitched in 1880 are fourth all-time among major leaguers, surpassed only by White’s 680 innings in 1879, Radbourn’s 678⅔ innings in 1884, and Guy Hecker’s 670⅔ innings pitching for the Louisville Eclipse in 1884.

34 Thirty years later, author/publisher Al Spink, in his groundbreaking National Game, called Dunlap “the greatest player that ever filled the [second base] position.” Alfred H. Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Co., 1910), 196.

35 League batting averages in 1880 dropped to .245 from .255 the year before, with team runs per game falling more than a half-run, to 4.69 from 5.31. For comparison, in 2023 the league batting average was .248, with teams scoring an average of 4.62 runs per game.

36 “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 18, 1880: 309.

37 “From a Pitcher’s Mouth,” Buffalo Express, January 27, 1881: 4.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Blues 2

Chicago White Stockings 0

National League Park

Cleveland, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.