July 27, 1947: West wins 15th annual Negro Leagues East-West Classic at Comiskey Park

There had been a Negro Leagues all-star game since September 10, 1933, when the first one was played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Often called the East-West Classic, or the Dream Game,1 by the early 1940s it attracted as many as 51,000 fans. Yet no matter how high the attendance figures were, the White-owned newspapers, including The Sporting News, ignored the game or gave it minimal coverage, while the Black press covered it enthusiastically.

There had been a Negro Leagues all-star game since September 10, 1933, when the first one was played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Often called the East-West Classic, or the Dream Game,1 by the early 1940s it attracted as many as 51,000 fans. Yet no matter how high the attendance figures were, the White-owned newspapers, including The Sporting News, ignored the game or gave it minimal coverage, while the Black press covered it enthusiastically.

But something was different in 1947: Jackie Robinson had integrated major-league baseball, and suddenly, sportswriters at the mainstream newspapers were trying to find out more about the top Black players; and scouts who had seldom seemed interested in the Negro Leagues were searching for the next Robinson.

One good place to see a large number of talented Black athletes was the 15th annual East-West Classic, scheduled for July 27 at Comiskey Park.2 Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier noted with amusement that “In the past, big league scouts were conspicuous by their absence during the East-West game. But boys and girls, times have changed. They’ll be there Sunday, eyeing everyone on the field…”3

Chicago Defender sports editor Fay Young agreed. He noted that four players for the West would undoubtedly be signed very soon: “Sammy Jethroe, Cleveland outfielder; Piper Davis, Birmingham Black Barons’ second sacker on whom the St. Louis Browns hold a 30-day option; Gentry Jessup, Chicago American Giants pitcher … and Reese ‘Goose’ Tatum, Indianapolis Clowns first sacker.”4

It was not just the Black press that noticed this sudden interest in the East-West classic: nationally syndicated columnist Charles Einstein wrote that “scouts from practically every big league club” would “set their sights on Chicago.”5 And Jack Clarke of the Chicago Sun observed that the quality of the talent at the East-West Classic was “outstanding,” as opposed to what the “bedraggled” Chicago White Sox team was putting on the field that year.6

The weather on game day was warm and humid, with temperatures in the low 90s, and a chance of showers. Baseball writers from numerous print publications crowded the press box, but the game does not seem to have been broadcast on local radio, the way the White Sox and Cubs games regularly were.

At about 3 P.M., the ceremonial first pitch was thrown by Chicago’s recently elected mayor, Martin H. Kennelly, and the game began. Newark Eagles manager Biz Mackey was in charge of the East squad, which had lost for the past four years in a row; the players were eager to break that streak. The East had some strong hitters, led by first baseman Johnny Washington of the Baltimore Elite Giants. He was having an outstanding year, hitting .406 by late July.7

The West team, skippered by Kansas City Monarchs manager Frank Duncan, had some good hitters too, including Piper Davis, who was hitting .359 with 17 home runs going into the East-West Classic. His Black Barons teammate and double-play partner, shortstop Art Wilson, was also on the West squad; Wilson had a .376 batting average thus far.8

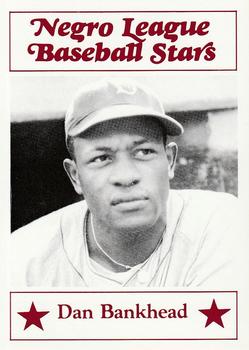

The crowd of more than 48,000 fans expected plenty of hitting, given the talent on both teams. But the East went quietly in the first. Not even slugger Johnny Washington could get on base against starting pitcher “Dangerous Dan” Bankhead of the Memphis Red Sox; Washington grounded out in his first at-bat, and he also went hitless in his other trips to the plate.9 As it turned out, he was not alone: the East mustered only three hits in the game.

Meanwhile, the West had little trouble hitting Newark Eagles pitcher Maxwell “Max” Manning, scoring two runs in the first. Kansas City Monarchs third baseman Herb Souell tripled, Cleveland Buckeyes outfielder Sam Jethroe brought him home on an infield out, Piper Davis hit a double, Buckeyes catcher Quincy Trouppe walked, and Memphis Red Sox left fielder José Colas singled, bringing Davis home.10

The East responded with a run in the second, although no slugging was involved: Bankhead hit Newark Eagles outfielder Monte Irvin in the side with a pitch, and Irvin, a speedy baserunner, made it to third on an infield out, scoring when outfielder Claro Duany of the New York Cubans flied out.

This brought the score to 2-1 and gave the fans of the East squad some hope, but that hope was short-lived. Bankhead gave up no other runs in the three innings he pitched, and the West jumped on Manning in the third.

It began when the Eagles’ pitcher hit Jethroe. Piper Davis flied out, but then Trouppe hit a triple, driving home Jethroe. Colas singled, bringing Trouppe home. Manager Biz Mackey brought in New York Cubans left-hander Luis Tiant to relieve Manning. Tiant gave up a single to Goose Tatum, but he then settled down and no more runs scored.11 After three, it was the West in command, 4-1.

Neither team scored again until the eighth inning. The East’s Tiant pitched 2⅔ scoreless innings, followed by Henry Miller of the Philadelphia Stars, who pitched the next two without allowing any runs. The West’s Gentry Jessup was very effective, setting down nine East batters in a row;12 veteran pitcher Chet Brewer of the Cleveland Buckeyes relieved him and retired the side in the seventh.

The East looked totally overmatched – they had been held to just one hit through seven innings. But in the eighth, their bats finally, and briefly, came alive. Outfielder Luis Marquez of the Homestead Grays hit a double, and catcher Lou Louden of the New York Cubans drove him in with a single, cutting the lead to 4-2.13

Fans of the East had little else to cheer about. The West came right back in the eighth, scoring a run off Homestead Grays pitcher Johnny Wright. Tatum singled, but was thrown out trying to steal second; outfielder Buddy Armour of the Chicago American Giants then hit a double; and Brewer redeemed himself for the run he just gave up, bringing Armour home with a single.14 The West led 5-2, and that turned out to be the final score.

While reporters from the Black press were pleased that the game attracted such a large crowd, they wished the East had been more competitive; this was the fifth time in six games the West had defeated them. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier didn’t pull any punches in his critique. He praised the West for putting a “powerful club on the field” with “pitching, hitting, and a stonewall defense.” But the same could not be said for the East: “The hitting was putrid, the pitching spotty, and in general it looked like a patched-up aggregation of second-stringers.”15

Other writers were more positive, especially those at the White-owned publications. Carl Hirsch of the Chicago Star said he saw “an impressive exhibition of Negro stars, with a substantial number of players who are obviously big-league timber.” He said it would be a “blunder” if the White Sox didn’t sign Gentry Jessup.16 And an article in the San Francisco Chronicle noted that the minor-league San Francisco Seals had their eye on Johnny Washington, Sam Jethroe, and several others.17

The 1947 season was “arguably the last year of high quality talent for Negro league baseball,”18 and the East-West Classic, once “the greatest show in the Negro sports world,”19 would soon diminish in importance, as more Black players signed major-league contracts. But in late July 1947, it could still attract nearly 50,000 fans, and showcase some of the Black baseball’s most talented stars.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Baltimore-based librarian Donna Hesson for research assistance; the author also thanks SABR members Jim Overmyer and John Fredland for their helpful suggestions.

This article was fact-checked by Stew Thornley and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

Among the sources used in this article were various SABR biographies, historical newspapers from the database Newspapers.com, as well as information from Retrosheet (https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/NgLg/B07270ASW1947.htm) and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Making Strong Bids for Berths in ‘Dream Game’ Voting,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 26, 1933, section 2: 5.

2 There has been some confusion about whether this was in fact the 15th annual all-star game: most Black sportswriters, including Wendell Smith and Fay Young, called it the 15th, but there had also been additional all-star games played in other cities on a few occasions. The stated reason was to bring the games to fans who did not live in the Midwest. For example, in 1939, an additional game was played at Yankee Stadium; in 1942, at Municipal Stadium, Cleveland; and in 1946, neither game was played at Comiskey – they were both at Griffith Stadium in Washington. Perhaps the sportswriters only counted the games at Comiskey Park, with the one exception being the 1946 games in Washington.

3 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1947: 14.

4 Frank “Fay” Young, “50,000 and Major League Scouts See West Beat East in Great Game,” Chicago Defender, August 2, 1947: 1, 11. Young was only partially correct in his prediction: Jethroe was eventually signed by Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the summer of 1948 and sent to the Triple-A Montreal Royals; in September 1949, Rickey sold Jethroe’s contract to the Boston Braves, and he went on to receive NL Rookie of the Year honors in 1950. The St. Louis Browns had a 30-day option on Piper Davis, but they let the option expire. Goose Tatum was scouted, but he seemed more interested in focusing on his successful basketball career with the Harlem Globetrotters. And Gentry Jessup was not signed by any major-league team.

5 “Field Day for Baseball Scouts,” St. Louis Star-Times, July 22, 1947: 17.

6 Jack Clarke, “Take It From Here,” Chicago Sun, July 26, 1947: 13.

7 Frank “Fay” Young, “50,000 and Major League Scouts See West Beat East in Great Game.”

8 Gene Kessler, “Negro Stars on Parade,” Chicago Daily Times, July 25, 1947: 58.

9 Wendell Smith, “The Sun Shines Brightly in the Golden West,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 2, 1947: 14.

10 Wendell Smith, “National Leaguers Helpless in Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 2, 1947: 15.

11 Frank “Fay” Young, “50,000 and Major League Scouts See West Beat East in Great Game.”

12 William Fay, “West Defeats East Negro Stars 5-2,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1947: 29.

13 Jack Clarke, “West Negro All Stars Win 5-2,” Chicago Sun, July 28, 1947: 17.

14 Frank “Fay” Young, “50,000 and Major League Scouts See West Beat East in Great Game.”

15 Wendell Smith, “National Leaguers Helpless in Classic.”

16 Carl Hirsch, “Calling Cubs, Sox! Here’s Just What the Doctor Ordered,” Chicago Star, August 2, 1947: 15.

17 “Negro Stars: 48,112 See West Take 5-2 Game,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 28, 1947: 15. Johnny Washington was not signed to a major-league contract; he remained with the Elite Giants. On the other hand, Dan Bankhead was signed by Branch Rickey and became the first Black pitcher in the major leagues on August 26, 1947.

18 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory – The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2006): 321.

19 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1947: 14.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.