July 3, 1958: Phillies’ Ed Bouchee returns to baseball after arrest

When has a criminal paid his or her debt to society? When has an apparent psychiatric disorder been cured, or at least managed? When does an offender who violated social mores deserve a second chance?

When has a criminal paid his or her debt to society? When has an apparent psychiatric disorder been cured, or at least managed? When does an offender who violated social mores deserve a second chance?

These are some of society’s weightier, knottier questions, and in an ideal world, people come to baseball parks to escape having to think about them. But those tough questions and considerations can work their way into the world of sports, becoming an unavoidable backdrop to the action on the field. Such was the case on the first Thursday afternoon of July 1958, when Philadelphia Phillies manager Mayo Smith wrote a familiar but long-absent name into the third spot on his lineup card.

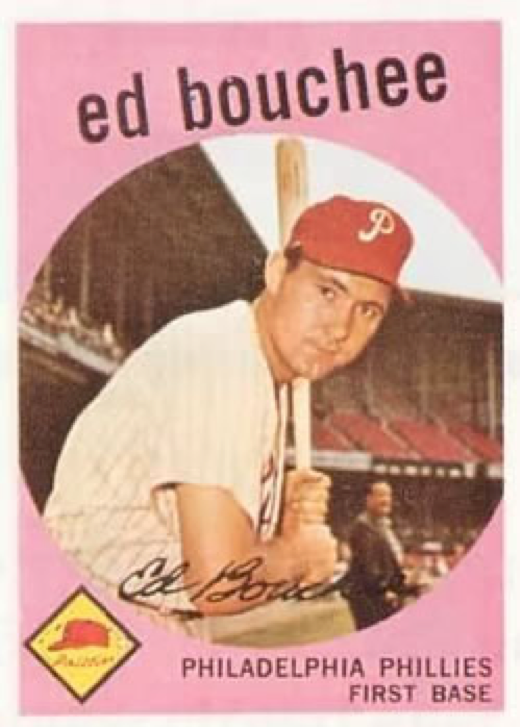

Rookie first baseman Ed Bouchee was one of the Phillies’ 1957 stars, breaking out to hit .293 with 17 home runs and 76 RBIs. The bulky, lefty-swinging Bouchee placed second to teammate Jack Sanford in National League Rookie of the Year voting, won the Sporting News NL Rookie Player of the Year award, and even placed 12th in Most Valuable Player voting. At 24, he seemed ticketed for a bright future as an anchor of the Philadelphia ballclub.

That changed on January 17, 1958, when police in Spokane, Washington, arrested Bouchee on charges that the ballplayer had exposed himself to young girls.1 Bouchee pleaded guilty to two counts of indecent exposure, charges carrying the potential for a 20-year prison sentence.2 A judge placed Bouchee on three years’ probation, while the Phillies announced his placement in a psychiatric treatment facility in Connecticut for an unspecified period of time.3

As Bouchee retreated from the public eye, it was initially unclear whether he would play in the major leagues again, and if so, when. Phillies general manager Roy Hamey was quoted in the March 12 issue of The Sporting News as saying, “The first thing we want to do is get him well. We hope he can play again some day.”4 But just a week later, the publication confidently assured readers that “all signs point to the probable return of last year’s rookie ace, Ed Bouchee, some time this season.”5 And news stories that spring made clear that the Phillies were a lesser team without their first baseman. One story from mid-May summarized matters: “The Phillies toured the West for the first time like a team on a see-saw. … [T]heir performances ranged from first-rate to forlorn. How much the loss of First Baseman Ed Bouchee meant became increasingly apparent.”6

By early June, Bouchee had been transferred to Philadelphia with doctors’ approval, on the grounds that regular contact with family and friends would be good for him.7 Later in the month, news stories indicated that Bouchee had earned clearance from his doctors, his teammates, and even the general public. Coach Benny Bengough, who oversaw Bouchee’s fitness training, was also assigned to bring him to public places in Philadelphia. Bengough reported: “The people we talked with patted Ed on the back and wished him luck. I think he has made the grade.”8

This left a difficult decision squarely on the desk of Commissioner Ford Frick. Frick made it clear that he would not persecute Bouchee just to make a point, but at the same time, he would not reinstate Bouchee just because the Phillies needed a first baseman.9 The commissioner undertook an exhaustive round of talks with the judge in Bouchee’s case; with psychiatrists; with Bouchee and his wife; with Bouchee’s teammates; and with representatives of the other seven National League teams. The verdict, Frick reported, was “strong and unanimous” in the player’s favor. Based on that feedback, Frick cleared Bouchee to return in the first week of July.10 It was not an unprecedented decision — Frick had earlier ruled on a morals case involving White Sox outfielder Jim Rivera11 — but it was a difficult one, and it remained to be seen whether the baseball community would truly welcome Bouchee.12

The Phillies entered the July 3 game tied for fifth place at 31-34 but only 6½ games out of first.13 The Braves, defending World Series champions, had a 39-29 record and sat in first place, three games ahead of the second-place Cardinals and Giants. Future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts started for Philadelphia, while Maine-born righty Carl Willey got the nod for Milwaukee. Willey, pitching in just his sixth big-league game and making his third start, was on his way to a rookie season that rivaled Bouchee’s for excellence. At year’s end, he posted a record of 9-7 and an ERA of 2.70 in 23 games, led the National League with four shutouts, and was named The Sporting News NL Rookie Pitcher of the Year.

The question of how fans would receive Bouchee was settled quickly, as he came to the plate in the top of the first inning with one out and second baseman Solly Hemus on first. The 17,624 fans on hand greeted him with what the Philadelphia Inquirer characterized as “a warm clatter of applause”14 and United Press International called “an ovation.”15 Bouchee, who later described himself as “nervous as hell,” took a called third strike from Willey. Left fielder Harry Anderson followed with a single, and Willey wild-pitched Hemus and Anderson up to third and second, but catcher Carl Sawatski ended the inning by grounding out to second.

The bottom end of the Phillies’ lineup got the team on the board in the top of the second. Third baseman Willie Jones was hit by a pitch, right fielder Bob Bowman doubled him to third, and shortstop Chico Fernandez drove in Jones with a groundball to second for a 1-0 Phillies lead. That score held for several innings, as Roberts granted the Braves a few singles but no real threats. The Phillies ran themselves out of a fourth-inning opportunity when slow-footed Sawatski tried to score from first on a double by Bowman. A relay from Braves center fielder Bill Bruton to shortstop Johnny Logan to catcher Del Crandall nipped Sawatski at home.

Those same three players helped the home team break through against Roberts in the bottom of the fifth. Logan doubled to right and advanced to third on a deep line out to center by Bruton. Crandall brought home the run with a fly ball to center, and the game was tied 1-1. Willey followed with a single — one of only five hits for him in the season — but Red Schoendienst grounded out to second to end the inning.

Bouchee logged two more unsuccessful trips to the plate, hitting a fly ball to center in the third and a groundball to shortstop in the sixth. Then came the top of the eighth, when he helped the Phillies suddenly and dramatically grab the lead. Second baseman Hemus was capable of hitting for power — he’d hit 15 home runs with the Cardinals in 1952 — and he hit a leadoff homer off Willey for a 2-1 Phillies lead. Bouchee followed with a shot to right-center, estimated at 385 feet, for a 3-1 lead.16 Willey shut down the Phillies for the rest of the inning, helped by a questionable baserunning decision that saw Anderson get thrown out trying to stretch a single, but the damage had been done.

In the top of the ninth, the Phillies got a double from Bowman and a walk by center fielder Richie Ashburn, but no runs. In the Braves’ ninths, left fielder Joe Adcock made things interesting with two outs when he tripled to right — the result of Bowman attempting an unsuccessful shoestring catch.17 It was only the second time a Braves runner had reached third base. Shortstop Logan, who had been to third in the fifth inning, promptly lofted a fly to Ashburn in center for the game’s final out. Roberts scattered six hits and one walk, striking out four, for his seventh win of the year and his 195th career victory. The game wrapped in 1 hour and 57 minutes. The Braves went on to repeat as National League champions, though they lost the World Series, while the Phillies slumped all the way to last place with a 69-85 record.

After the game, Bouchee told reporters he hadn’t heard any comments from the crowd. He added, “I just want to play baseball. I understand my problem and that means a lot.”18 While his big-league career lasted only a few years longer — capped off by a .161 batting average amid the shambles of the 1962 Mets19 — it appears that he did understand his problem, as he was never known to have re-offended, and the remainder of his life was uneventful. Bouchee died in Phoenix, Arizona, in 2013, a few months shy of 80 years old.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for general player, team and season data. I also consulted the game box score in the July 16, 1958, issue of The Sporting News.

baseball-reference.com/boxes/MLN/MLN195807030.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1958/B07030MLN1958.htm

Photo: Image of 1959 Topps card #39 downloaded from the Trading Card Database. (As is well known, there is no 1958 Ed Bouchee Topps card.)

Notes

1 Headlines in many newspapers across America described the charges as “child molesting.” The stories generally, but not always, included the detail that the children had not been physically harmed.

2 “Baseball Player Admits Charges,” Spokane (Washington) Statesman-Review, February 21, 1958: 1.

3 “Bouchee Given 3 Yrs. Probation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1958: 38.

4 “Bouchee Put on Probation; Phillies to Aid in Treatment;” The Sporting News, March 12, 1958: 24.

5 “Anderson’s Play at Gateway Takes Heat Off Philly Trade,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1958: 10. In the article, this information was not credited to any specific source.

6 Allen Lewis, “Semproch Boomed to Follow Sanford as Top Hill Rookie,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1958: 15.

7 Allen Lewis, “Bouchee Listed for June Swat Drills in Philly,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1958: 18.

8 “Bouchee Claims He’s Fit, Waits for Frick’s Okay,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1958: 10.

9 “Bouchee Claims He’s Fit, Waits for Frick’s Okay.” Others who manned the first-base bag for the Phillies that season included outfielder Harry Anderson (49 appearances), outfielder Dave Philley (18 appearances), infielder Pancho Herrera (11 games) and third baseman Willie Jones (one game).

10 Retrosheet’s 1958 game log for Bouchee confusingly credits him with appearances in three games in June. All three games were suspended for curfew and completed later in the season, after Bouchee’s return to the roster.

11 Rivera’s case, which happened at the end of the 1952 season, is detailed in his SABR biography, written by Richard Smiley.

12 Dan Daniel, “Frick Reinstates Ed Bouchee on Probation Basis,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1958: 23. Daniel’s story also says that “some fans” were critical of the Phillies for bringing Bouchee back in midseason, rather than at spring training in 1959.

13 The suspended games mentioned in Note 10 are not included in the standings. Going into the July 3 game, the Phillies had completed 66 games, the fewest in the National League.

14 “Hemus, Bouchee Homer, Phillies Win, 3-1,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 4, 1958: 12.

15 Associated Press, “Was Nervous as H—,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1958: 49.

16 Associated Press, “Bouchee Hits Homer, Phils Dump Braves,” Miami (Florida) Herald, July 4, 1958:1B.

17 “Hemus, Bouchee Homer, Phillies Win, 3-1.”

18 “Was Nervous as H—.”

19 Bouchee holds a tiny sliver of immortality in Mets history: He was the team’s first pinch-hitter, drawing a walk in the fourth inning of the team’s first game on April 11, 1962.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 3

Milwaukee Braves 1

County Stadium

Milwaukee, WI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.