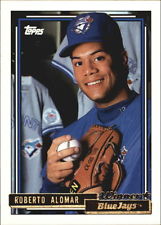

October 11, 1992: Alomar, Blue Jays emerge out of shadows in ALCS Game 4

When Blue Jays second baseman Roberto Alomar stepped into the late-afternoon shadows at home plate in the top of the ninth inning, a figurative darkness overshadowed Toronto as well. Needing two runs to tie the game, time was running out for the Blue Jays to rally. Toronto trailed 6-4 in Game Four of the 1992 American League Championship Series and was three outs away from a loss that would even their series against the Athletics at two games apiece.

When Blue Jays second baseman Roberto Alomar stepped into the late-afternoon shadows at home plate in the top of the ninth inning, a figurative darkness overshadowed Toronto as well. Needing two runs to tie the game, time was running out for the Blue Jays to rally. Toronto trailed 6-4 in Game Four of the 1992 American League Championship Series and was three outs away from a loss that would even their series against the Athletics at two games apiece.

Alomar dug in against Dennis Eckersley.

All-Star vs. All-Star.

Best vs. best.

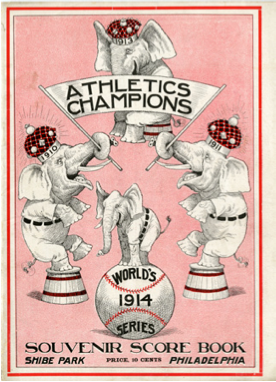

It was the apical moment of the Toronto-Oakland rivalry that had simmered over the past few years. Since 1985 both clubs had won their respective division four times. Yet in the postseason the Blue Jays always fizzled while Oakland sizzled. The Athletics added three pennants and the 1989 World Series title after easily pushing aside the Blue Jays in a five-game ALCS that ended tersely. In the ninth inning of the final game, Toronto manager Cito Gaston asked the umpires to check if Eckersley was scuffing baseballs. An insulted Eckersley shouted profanities at an irate Gaston who fired right back at the Oakland closer after the game.[fn]Dave Perkins, “’I don’t cheat,’ Eck rasps at Cito,” The Toronto Star, October 9, 1989.[/fn]

In Game Four of the 1992 ALCS Oakland jumped out to a 6–1 lead, and the Toronto bats looked lifeless entering the eighth inning. Suddenly, however, Alomar led off with a double, chasing Oakland starter Bob Welch and ushering in reliever Jeff Parrett. Alomar promptly stole third and scored on a Joe Carter single. After Dave Winfield singled Carter to third, Oakland manager Tony La Russa had seen enough. With the potential tying run on deck, he signaled for Eckersley from the bullpen.

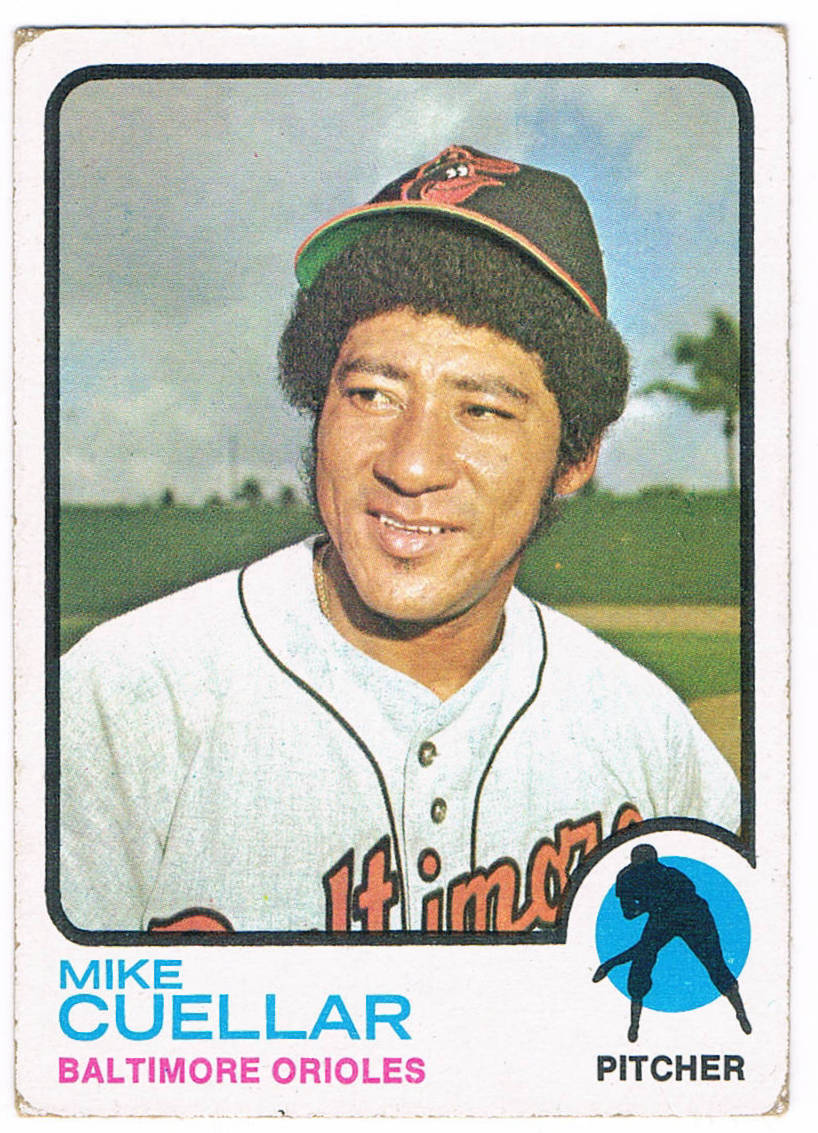

The Oakland-born Eckersley, 37, was a six-time All-Star, widely acknowledged as the best closer in the game. He started 1992 with 36 straight saves en route to a major league-leading 51.[fn]Craig Barbarino, “1992 Year in Review,” The Official Major League Baseball Program — World Series (1992): 29.[/fn] Since 1988, Eckersley has been simply dominant. No reliever in either league recorded more saves, 220, had a lower walks + hits per innings pitched ratio (WHIP), 0.792, or had a strikeout-to-walk ratio (K/BB), 9.95, that was even half as good as his mark.[fn]http://bbref.com/pi/shareit/sX3xf[/fn] His 10 career LCS saves were already a record that would not be broken until 2009.[fn]http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/LCS_pitching.shtml[/fn]

But on this afternoon, Toronto was not interested in history, only in stringing together hits to climb back into the game. The next two Toronto hitters — John Olerud and Candy Maldonado — attacked early, each jumping on Eckersley’s first pitch for run-scoring singles, cutting the Athletics’ lead to 6–4, putting the tying runs on first and second. Eckersley squashed the rally, however, coolly retiring the next three batters, ending the inning with a strikeout of pinch-hitter Ed Sprague. Following the strikeout, Eckersley pumped his fist, and then yelled and pointed at the Toronto dugout. Immediately, the Blue Jays bench rose up indignantly. “It was a little gesture and the guys responded. We got very, uh, vocal. It’s a good thing the TV cameras weren’t in the dugout,” Winfield said.[fn]Rosie DiManno, Glory Jays: Canada’s World Series Champions (Champaign, IL: Sagamore Publishing, 1993), 252–253.[/fn] “He should know to let sleeping dogs lie. You don’t wake ‘em up. It’s a cardinal sin in baseball,” added Toronto starter Jack Morris.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Eckersley later downplayed his actions. “Aw hell, I was just excited. I mean, things were starting to slip away and I thought that strikeout of Sprague was the ballgame. Sometimes I do crazy stuff, but I didn’t mean to show those guys up. It was just a reaction to the moment.”[fn]Tom Cheek and Howard Berger, Road to Glory: An Insider’s Look at 16 Years of Blue Jay Baseball (Toronto: Warwick Publishing, 1993), 299.[/fn]

In the ninth, as darkness enveloped the home plate dirt, leadoff hitter Devon White lined a single to left field, then raced all the way to third when Rickey Henderson misplayed the ball. Up stepped Alomar, representing the tying run.

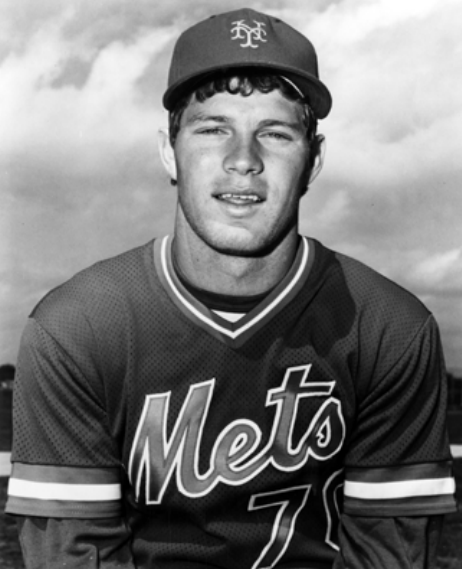

Alomar, 24, and already a three-time All-Star and two-time Gold Glove Award winner, was the son of 15-year veteran Sandy Alomar and brother of 1990 AL Rookie of the Year Sandy Alomar Jr. The Toronto second baseman was considered one of the best young all-around, five-tool players in baseball. Alomar had already generated 23.3 wins above replacement (WAR) in his first five seasons. Only four other second baseman before him had accumulated at least that many WAR over the first five seasons of their respective careers, and he was the first to do so since Jackie Robinson 41 years ago.[fn]http://bbref.com/pi/shareit/P4eOo[/fn]

Carter had given Alomar some simple advice moments before in the on-deck circle: “Look for a strike … hit the ball hard and try to keep the inning going.”[fn]Dave Perkins, “Alomar’s heroic homer a shot heard around Blue Jays’ world,” The Toronto Star, October 12, 1992.[/fn] With the count 2-2, Eckersley fired. Alomar swung, immediately dropped his bat and thrust both arms upward in triumph as he slowly trotted up the first-base line out of the darkness at home plate into the sunshine of the basepath, knowing his line drive would clear the right field wall. When the ball landed just to the left of a policeman standing on a stairway beyond the fence, Alomar continued to slowly circle the bases. The entire Toronto bench rose up, shouting, gesturing, and staring out at the stunned Eckersley.

“Eck stuck it in our faces and we kicked his ass,” a fired-up Morris thundered, after the game. “We’re happy as hell about it. I used to do a lot of gesturing and stuff like Eck does … and I realized I had to change. You just don’t go around trying to show teams up — it may finally have come back to hurt him today.”[fn]Tom Cheek and Howard Berger, Road to Glory: An Insider’s Look at 16 Years of Blue Jay Baseball (Toronto: Warwick Publishing, 1993), 299–300.[/fn]

For the tying run, Alomar emphatically jumped on home plate with both feet. It was his fourth hit and fifth consecutive time reaching base on the day. The Blue Jays had finally broken through. On one swing of Alomar’s bat, the constant disappointment of postseasons past seemed to melt away. His game-tying home run was not only the biggest clutch hit in Blue Jays’ history, but it lifted the franchise to uncharted territory: Never before had a Toronto player come through under intense playoff pressure as Alomar had, rejuvenating his team when all hope looked lost.

“This was the greatest game of my career, and that home run was the best thing that ever happened in my life,” gushed Alomar. “As soon as I made contact, I knew it was out of there. As I was rounding the bases, I was thinking, ‘Yeah, that ball is gone, gone, GONE!’. Analyzing the at-bat, Alomar continued, “That’s not the Eckersley I’ve come to know. He wasn’t throwing the good slider he usually does — it was flat and his fastball wasn’t moving that much. On the home run, I was hoping he’d come inside and he did.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

A somber Eckersley was matter-of-fact about what transpired. “Hey, it’s Toronto’s day. They hit the f*** – out of me . . . I just couldn’t stop the bleeding. That’s as hard as I’ve gotten hit since I can remember. Failure of this magnitude is tough to handle. I wanted to throw it down and away but I threw it high and he hit the s***out of it. What can I say? It’s going to be tough to sleep tonight.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

The remainder of the game was similarly pressure-packed. Toronto nearly took the lead after Alomar’s home run by loading the bases, but reliever Jim Corsi retired Pat Borders on a groundout to end the inning. For Eckersley, it was his final postseason appearance in an Oakland uniform.

In the last of the ninth, the Athletics were 90 feet from winning the game, but with one out fireballer Duane Ward got Terry Steinbach to hit a grounder to second. Alomar came up throwing to the plate to gun down pinch-runner Eric Fox, and one pitch later Carney Lansford grounded into a fielder’s choice to send the game to extra innings.

Finally, in the top of the 11th, Toronto took the lead. Derek Bell worked a nine-pitch leadoff walk, and moved to third on the next pitch when Maldonado, again attacking early, punched a single to right field. With one out, Borders lined to left, deep enough so that Bell could tag and score. In the bottom of the inning, Toronto closer Tom Henke threw just 13 pitches to lock down the most improbable victory in Blue Jays history, and ending the longest game in ALCS history at that time (4 hours and 25 minutes).[fn]“Extra-inning affair marks longest game in AL playoff history,” The Toronto Star, October 12, 1992.[/fn]

The Blue Jays became the first team in postseason history to come back and win after trailing by at least five runs after seven innings.[fn]Jack Curry, “THE PLAYOFFS: Who’s Sorry Now? The A’s, Not Jays,” The New York Times, October 12, 1992.[/fn]

Somehow, Toronto had the 7–6 victory, a 3–1 ALCS lead, and the psychological edge of knowing it could beat the best, Eckersley, the winner of both the 1992 Cy Young and Most Valuable Player Awards. The game was a gilded building block in Toronto’s path to eventually winning its first World Series two weeks later in Atlanta. It would not have been possible, however, had Alomar not struck the biggest blow, helping Toronto emerge from the shadows of another possible ALCS defeat and ultimately triumph.

Additional Stats

Toronto Blue Jays 7

Oakland A’s 6

11 innings

Game 4, ALCS

Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum

Oakland, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.