October 7, 1935: Tigers’ Goose Goslin wins World Series with walk-off single

The Detroit Tigers had been to the World Series four times in their 34-year history. Four times, they had suffered defeat. On October 7, 1935, the Tigers, along with the entire city of Detroit, were thirsty for victory, hoping that the fifth time would be a charm. As that Monday morning dawned, the team found itself up three games to two against the Chicago Cubs in the 1935 World Series. Navin Field buzzed with anticipation, as 48,420 giddy Detroit fans jammed their way into the ballpark at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

The Detroit Tigers had been to the World Series four times in their 34-year history. Four times, they had suffered defeat. On October 7, 1935, the Tigers, along with the entire city of Detroit, were thirsty for victory, hoping that the fifth time would be a charm. As that Monday morning dawned, the team found itself up three games to two against the Chicago Cubs in the 1935 World Series. Navin Field buzzed with anticipation, as 48,420 giddy Detroit fans jammed their way into the ballpark at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.

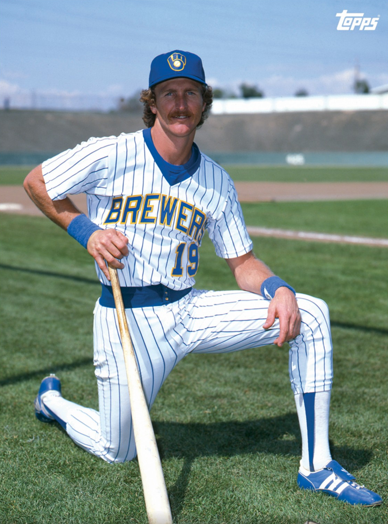

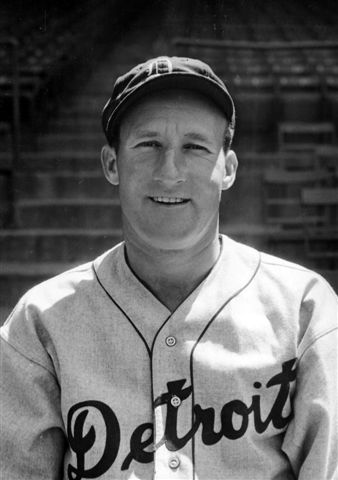

Twenty-one-game winner Tommy Bridges took the mound for Detroit, while Chicago countered with Larry French, who had won 17 during the regular season. If the Tigers were to prevail this afternoon, they would have to once again do it without the services of their young slugger Hank Greenberg, who hadn’t played since Game Two after injuring his wrist. This was a star-studded Detroit team, with no less than four future Hall of Famers (Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Goose Goslin and catcher-manager Mickey Cochrane). The Cubs, as well, had their own share of stars destined for Cooperstown, including Gabby Hartnett, Billy Herman, Chuck Klein and Freddie Lindstrom (although the latter did not play in this game).

The score was tied at three entering the fateful ninth. Tommy Bridges was still on the mound for Detroit. Stan Hack led off by stroking a long triple over the head of Gee Walker in center, and it looked like Chicago was going to take the lead. Bridges, however, in a gutsy display of pitching, retired the next two batters on a strikeout and a roller back to the mound, Hack remaining on third. Bridges quickly got two strikes on Augie Galan. Then came what Tigers owner Frank Navin later called “the most important play of the Series.”1 Bridges bounced an errant curve ball two feet in front of the plate, but Cochrane got down on his knees and was able to block it — barely. Hack, the potential go-ahead run, was forced to scamper back to third. On the next pitch, Galan swung and hit a high popup into short left field. Shortstop Billy Rogell, third baseman Flea Clifton, and left fielder Goslin all converged on it, while Hack raced for home. It was Goslin who made the catch, dashing toward the infield. The crowd went delirious. No runs, one hit, no errors. Improbably, the score remained tied, 3-3.

Years later, Billy Herman would still lament Cochrane’s splendid play: “When I think back to the 1935 World Series, all I can see is Hack standing on third base, waiting for somebody to drive him in. Seems he stood there for hours and hours.”2

Charles P. Ward wrote in the next day’s Detroit Free Press, “Those who saw defeat staring the Tigers in the face failed to remember that Bridges is one of the gamest little men that ever came out of the hills of Tennessee. He was sent into the game by Cochrane because Mickey wanted to have somebody on the mound who would show the Cubs plenty of gameness even if he didn’t have much on the ball.”3

And then came the bottom of the ninth. With one out, Cochrane reached on an infield single, Gehringer hit a sharp smash to Phil Cavarretta, the Chicago first baseman, who bobbled the ball momentarily before stepping on first to retire Gehringer. His throw to second was too late to nab Cochrane. Goose Goslin ended the affair with a single into right, just over the head of second baseman Billy Herman. Cochrane raced around third and headed home with the winning run. The Tigers were World Series winners for the first time in their history, and Navin Field erupted into pandemonium.

“They will remember the manner in which the base ball [sic] championship of 1935 was won as long as they remember the team that won it,” wrote H.G. Salsinger the next day in the Detroit News. “There have been better teams than Detroit in the past but no team ever won a World Series more spectacularly than Detroit won the one that ended with two out in the ninth inning at Navin Field yesterday.”4

“The greatest exhibition of pitching in the clutch I have ever seen,” exclaimed a jubilant Cochrane in the postgame celebration, referring to Bridges’ ninth-inning heroics. “I told those Cubs that we’d throw 150 pounds of heart at them out there today, and I guess they realize now that Little Tommy is all of that — after that ninth inning. Pitching! He threw the six greatest curves I ever caught to lick them. … That Bridges. What a thrill he gave me. That little guy has the heart of a lion. … What a pitcher, what a heart. Just 150 pounds of grit and courage. That’s what he is.”5

In downtown Detroit, euphoric crowds jammed the streets, dancing and celebrating throughout the afternoon and into the evening. Automobiles clogged the length of Woodward Avenue. A carnival spirit spread everywhere in the city.

The Detroit Free Press put it down for posterity the next day:

Police said the crowd was bigger than the Armistice Day crowd of 1918. Even in that glorious moment no such crowds had choked Detroit streets; no such paralysis of transportation had ensued; no such heights of pandemonium had been reached.

Detroit, through the baseball team that is a symbol and the incarnation of its fighting spirit, had won the baseball championship of the world, and the world was to know it.

It was Detroit’s salute to America.

Detroit had the dynamite; Mickey Cochrane and his Tigers provided the spark.

Detroit celebrated because it had won the world championship.

It celebrated because it was the city that had led the nation back to recovery.

It celebrated because it was the city that wouldn’t stay licked; the city that couldn’t be licked.

It was Detroit the unconquerable, ready to tell the world when the moment arrived.

The moment had arrived, and the world was told.

“There’s no doubt,” Police Inspector William Maloney said, “that it’s the biggest crowd in downtown Detroit in my memory.” And, he added, he has a very long memory.6

Meanwhile, back in the celebratory clubhouse, Cochrane managed to locate Goslin and Bridges among the mayhem. Grasping them both around their necks, he planted a kiss on each of them while flashbulbs popped.

“What a thrill! What a game to win! What a heart that Bridges has! What a money player that Goslin is! What a team the whole damned gang is! I’ve had many big moments in my life, but none to equal the thrill of crossing the plate with the winning run. Boy, that was great. I thought I never would get there.”7

This article appeared in Tigers By The Tale: Great Games at Michigan and Trumbull” (SABR, 2016), edited by Scott Ferkovich. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com were also accessed.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET193510070.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1935/B10070DET1935.htm

Notes

1 John Rosengren, Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes (New York: New American Library, 2013), 126.

2 Charles Bevis, Mickey Cochrane: The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998), 6.

3 Charles P. Ward, “Detroit Wins World Championship,” Detroit Free Press, October 8, 1935.

4 H.G. Salsinger, “Cochrane, Goslin Share Hero Role with Bridges,” Detroit News, October 8, 1935.

5 W.W. Edgar, “Wild Scenes Are Enacted in Tigers’ Dressing Room,” Detroit Free Press, October 8, 1935.

6 “Detroit Hails its Champion Tigers as a Symbol of the City Dynamic,” Detroit Free Press, October 8, 1935.

7 Edgar, “Wild Scenes.”

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 4

Chicago Cubs 3

Game 6, WS

Navin Field

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.