September 20, 1945: Cleveland Buckeyes dethrone Negro League champion Homestead Grays

The Homestead Grays were a dynasty in Negro League baseball in the 1940s. They had won back-to-back world championships in 1943-1944 and seven Negro National League pennants in eight years. Their roster was full of a who’s who of Negro League stars, several of whom would one day be recognized for their greatness in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In September of 1945, however, the Grays legends were also up in age: Jud Wilson (49), Cool Papa Bell (42), Buck Leonard (37), Ray Brown (37), Jerry Benjamin (35), Jelly Jackson (35), Sam Bankhead (34), and a comparatively “young” Josh Gibson (33). By contrast, the average of the Buckeyes was under 30.

The Homestead Grays were a dynasty in Negro League baseball in the 1940s. They had won back-to-back world championships in 1943-1944 and seven Negro National League pennants in eight years. Their roster was full of a who’s who of Negro League stars, several of whom would one day be recognized for their greatness in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In September of 1945, however, the Grays legends were also up in age: Jud Wilson (49), Cool Papa Bell (42), Buck Leonard (37), Ray Brown (37), Jerry Benjamin (35), Jelly Jackson (35), Sam Bankhead (34), and a comparatively “young” Josh Gibson (33). By contrast, the average of the Buckeyes was under 30.

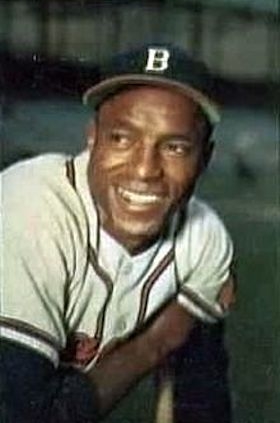

While Negro League records are often incomplete, there was no denying who the Buckeyes hitting star was. Reports listed Sam “The Jet” Jethroe, so-called because of his blazing speed, as batting .393 with 123 total bases, 10 triples, 8 home runs, and 21 stolen bases. Jethroe had been involved in a “tryout” at Fenway Park with Jackie Robinson during the season, as White baseball owners were feeling the pressure to integrate the game. The tryout was more of a publicity stunt, remembered more for a racial slur hurled at them from somebody at the ballpark, but Jethroe became Boston’s first Black major leaguer when he suited up for the National League’s Braves.

The Buckeyes’ strength was their pitching. Brothers George and Willie Jefferson had 16-1 and 14-2 seasons, respectively, while Eugene Bremer was 12-5.

Harry Walker, Mo Harris, Jimmy Thompson, and Fred McCleary were the umpiring crew for the series.

The first two games were held in Cleveland: Game One at Cleveland Stadium and Game Two at League Park. Both ballparks were home to the Cleveland Indians, and both teams were forced to suit up in the visitors’ locker room. The Buckeyes also relied on discarded Indians uniforms, which were a cherished possession since the name “Cleveland” was embroidered across the front. In Game One before a crowd of 6,500, the dominant pitching of Willie Jefferson powered the Buckeyes to a 2-1 victory over the Grays. Game Two saw a wild finish akin to a “story-book thriller” (in the Call & Post’s description).1 Cleveland rallied from 2-0 down as over 10,000 shivering fans looked on. The Buckeyes tied the score in the seventh, then Bremer sent them home with jubilation with a bases-loaded walk-off hit to secure a 3-2 win.2

After Game Two, the teams boarded the bus and headed south to Pittsburgh. A rainout, however, caused Game Three game to be moved to Griffith Stadium in Washington, where George Jefferson shut out the Grays, 4-0, on three hits.

Game Four was played at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park and pitted Big Frank Carswell on the hill for the Bucks against Ray Brown for the Grays. The Buckeyes jumped out on top early. Avelino Cañizares, dubbed “the Cuban sensation” by Jimmy Jones of the Call & Post, reached on an infield single.3 Archie Ware walked, then Jethroe beat out a dribbler to the mound that Brown couldn’t secure, and the bases were loaded. Parnell Woods, called “one of the greatest clutch hitters in the game” by Jones, scorched a grounder to second too hot to handle for Bee Jackson, and Cañizares and Ware scored. Jackson recovered in time to get Jethroe at second to end the inning.4

Only in the third inning did Carswell find trouble. He was helped when Bankhead hit into a double play, erasing Jud Wilson, who had been hit by a pitch. But Ray Brown walked and Benjamin’s single put runners at first and third. A walk to Bell loaded the bases, but a grounder by the 19-year-old Dave Hoskins forced Bell at second, and the Grays’ best opportunity went by the boards.

The Buckeyes added a run in the fourth when Willie Grace singled and later scored on a long fly ball by Johnnie Cowan, to give the Buckeyes a 3-0 lead.

In the seventh, Cowan singled and Carswell was safe as first baseman Leonard let his roller pass him as he was busy praying for it to spin foul. Cowan snuck all the way to third during the blunder. Cañizares bunted Carswell to second, but Cowan had to hold. Ware flied to Bell in left, not deep enough to score a run, and it looked as if the Grays would get out of the inning unscathed. It was not to be, however, as “the league leading wonder batman” – as Jones described Jethroe – came to the plate. His second hit of the game was punched into center field and the Buckeyes added a pair to grab a 5-0 lead.5

Carswell continued for the 5-0 shutout, allowing only four hits to the Grays’ superstar lineup.

“Nobody gave us a chance,” Willie Grace observed over 50 years later. “But we had a great club ourselves. We were fast and we had good pitchers and fielders. I think we surprised them. They thought they were going to sweep us. If we played them a month later, or a week earlier, we probably wouldn’t have beaten them. The timing was right.”6

Bob Williams, sports editor of the Call & Post, recalled the Buckeyes’ short history, dating from 1941. Ernie Wright, an Erie, Pennsylvania, businessman, drove up to a shoeshine parlor in Cleveland and made an offer to the man standing there. “Are you Wilbur Hayes?” he asked the local sports promoter. “How’d you like to start up a baseball club, with me as a backer?” The team was born, but its early life wasn’t all enjoyable. During its inaugural season, the team had to travel by cars when the team bus broke down. Tragedy struck on September 7, 1942, when one of the cars was in an accident that claimed the lives of two players. The championship was even sweeter considering the Buckeyes’ overcoming such sorrow. “At the end of the series,” Williams wrote, “we found ourselves staring into the faces of these boys who had been given so little credit as they marched towards their world championship. Yep, we found ourselves staring into the individual faces of these fellows whose united efforts had brought them the highest honor in all Negro baseball.”7

“They are not individual stars,” umpire Harry Walker reflected in his own Call & Post column, “but a star team that plays with a lot of team work, and they have taken the East. They are all a nice group of gentlemen.”8

A “Cinderella team” is how Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier described the Buckeyes, who, “fired by determination and youth … pulled one of the biggest surprises in baseball history.” While also acknowledging the greatness of the Grays, Smith also noted the passage of time and the Grays “creaking in the joints, in dire need of replacements, and exhausted from that last siege when they had to win nine games in six days to beat out Baltimore and Newark (for the pennant); the Grays just didn’t have it in ’em against the inspired, fiery Clevelanders.”9

A half-century later, Jethroe mentioned a touch of irony. “We beat them in four straight games. Then we continued playing them (in exhibitions) and never won another game.”10

But they won the games that mattered, through pitching, defense, and a lot of heart, despite being mostly ignored by the white press. Their legacy still stands, as those gathered at Shibe Park that day saw those traits that supersede the color of one’s skin. Later that fall, Jackie Robinson signed with the Montreal Royals, a Brooklyn Dodgers farm team. His next step was the major leagues and a newly integrated American pastime.

Sources

The author would like to thank Stephanie Liscio, Rick Bush, and the Cleveland Public Library for research assistance. Readers who would like more information on Negro League baseball in Cleveland are referred to Liscio’s book, Integrating Cleveland Baseball: Media Activism, the Integration of the Indians and the Demise of the Negro League Buckeyes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010).

https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1945/B09201HOM1945.htm

BR Bullpen, “1945 Negro League World Series,” Baseball-Reference.com, baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1945_Negro_World_Series. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

“Cleveland Buckeyes.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University, case.edu/ech/articles/c/cleveland-buckeyes. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

“Here’s Buckeye Pitching Staff, Rated Peerless,” Cleveland Call & Post, September 15, 1945.

Jones, Jimmy. “Buckeyes Grab First Game of Series, 2-1, Carry On in Fight with Mighty Grays,” Call & Post, September 22, 1945: 6B.

“Sammy Jethroe Again Bucks’ Most Valuable Player, League Leader in Almost Every Batting Honor,” Call & Post, September 15, 1945.

Notes

1 The Call & Post, founded in the late 1920s and based in Cleveland, covers news of interest to the African-American community.

2 “Second Win for Buckeyes Is Like Story-Book Thriller; Bremer Wins Own Game, 3-2,” Call & Post, September 22, 1945: 6B.

3 Jimmy Jones, “Series Victor of 4-in-Row, Bucks Stand Out as All-Time Greats, Carswell Wins No. 4,” Call & Post, September 29, 1945: 6B.

4 Jones.

5 Jones.

6 Bob Dolgan, “Championship Memories: The Underdog Cleveland Buckeyes Were Negro League Champs in 1945,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 26, 1996: 1C.

7 Bob Williams, “Sports Rambler,” Call & Post, September 29, 1945: 6B

8 Harry Walker, “World Series – Dots and Dashes,” Call & Post, September 29, 1945: 7B.

9 Wendell Smith, “The Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 29, 1945: 12.

10 Bill Lammers, “The Cleveland Buckeyes: Champions of a Forgotten League,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 14, 1992: 10.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Buckeyes 5

Homestead Grays 0

Game 4, Negro League World Series

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.