Baseball and Classic Television: A Brief Overview

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors

One could pen a book or perhaps even an encyclopedia on the manner in which baseball and television have merged across the decades. Such a volume not only would explore the manner in which ballgames have been broadcast on TV both locally and nationally and the celebrated sportscasters who announce them. It would feature everything from the history of baseball stars hawking products or appearing as guests on talk shows or quiz shows to the presence of the sport and its players on TV series.

For indeed, baseball on the small screen transcends game broadcasts and recaps on the evening news. Take, for example, ballplayers appearing in commercials. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, the inimitable Yogi Berra peddled the Yoo-Hoo chocolate drink (“Who says Yoo-Hoo’s just for kids?”); more recently before his death, he advertised AFLAC, the supplemental insurance provider. (“And they give you cash, which is just as good as money.”) Ballplayers have been associated with a rainbow of products, from Mr. Coffee (Joe DiMaggio) to Advil (Nolan Ryan) to Nike (Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, Ken Griffey Jr., Don Mattingly, Bo Jackson …). An iconic but long-retired athlete even can win new fame among the emerging generations by appearing in a popular television ad. Such is the case with Joe D. He first became the Mr. Coffee spokesperson in 1974, 23 years after ending his playing career and six years after Simon and Garfunkel asked, in the lyrics of the chart-topping song “Mrs. Robinson,” “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?” To many of those growing up in the 1970s, Joltin’ Joe was more identified as the pitchman for Mr. Coffee than as the New York Yankees Hall of Famer who fashioned a 56-game hitting streak, or even as Marilyn Monroe’s ex-husband.

Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays in a 1980 Blue Bonnet margarine commercial posed wearing bonnets eating corn with a tub a margarine in the foreground. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The list of ballplayers hawking products on TV is endless. In one comical ad, bonnet-clad, corn-chomping Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays harmonize the lyrics “Everything’s better with Blue Bonnet on it.” In another, Billy Martin and George Steinbrenner argue the merits of Lite Beer from Miller, with the manager claiming that the product is “less filling” and the owner overriding him with the opinion that it “tastes great.” In one ad, Don Drysdale hypes a series of baseball cards, found on Post cereal boxes, which feature the likenesses of 200 star players; in another, he shells for Poolsaver, a motorized swimming-pool cover. A veritable all-star team covering the generations – CC Sabathia, Evan Longoria, Jim Thome, Carlton Fisk, Lou Piniella, Rickey Henderson, Rollie Fingers, Randy Johnson, Ozzie Smith – join up for a Field of Dreams-inspired Pepsi ad. And so on …

In recent decades, the latest World Series hero or MLB icon will strut across a stage and heartily grasp hands with a late-night TV host. One of countless examples: In a piece penned in 2014, when David Letterman announced his retirement from late-night television, ESPN’s Jim Caple surveyed his baseball connection. Back in 1986, Letterman spent an entire show paying homage to Harmon Killebrew. Ted Williams was a guest in 1993; Hank Aaron appeared on several occasions; Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, and Andy Pettitte celebrated their World Series triumph in 2009; and Bud Selig and David Ortiz were on the show in 2013. Various Letterman “Top 10 Lists” highlighted the sport. In one, Curt Schilling recited the “Top 10 Secrets Behind the Red Sox 2004 Comeback”; topping the list was “We got Babe Ruth’s ghost a hooker and now everything’s cool.” Regarding the “Top 10 Good Things About a Possible Baseball Strike,” Letterman quipped, “Fun to think with each passing day Alex Rodriguez is out another 85 grand”; one of the “Top 10 Things Going Through A-Rod’s Mind” after he was hit by a 3-and-0 pitch in his left bicep was, “Hey, that’s my injection arm.” But the host not only spotlighted baseball celebs. On one 1985 show, he referred to Terry Forster as a “fat tub of goo” – and the chunky relief pitcher eventually came on the show. He arrived onstage chomping on a “David Letterman sandwich,” which he described as a delicacy with “a lot of tongue on it.” Forster admitted that while in the bullpen he would exchange autographed baseballs for hot dogs with fans; his favorite ballyard was “Houston,” where “big tubs of beer” could be purchased for “a buck seventy-five.”1

These days, the home-run derby has become a staple of the All Star Game TV lineup; back in 1960, Home Run Derby was a TV series that featured sluggers from Hank Aaron and Bob Allison to Wally Post and Willie Mays battling each other in home run-hitting contests filmed at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field, a conveniently located venue employed in endless baseball films and TV shows. Conversely, in the medium’s earliest years, so many shows were broadcast live from New York City-based studios – and quite a few New York Yankees, New York Giants, and Brooklyn Dodgers made appearances. One even was the first-ever “mystery guest” on What’s My Line? (1950-1967), the popular prime-time CBS game show. He was Phil Rizzuto, the beloved Bronx Bomber “Scooter,” and the date was February 2, 1950. Years before he morphed into an aging self-caricature on Yankees broadcasts whose “holy cannoli” banter was at once cherished and lampooned, Rizzuto was quiet and serious-minded in this and his other What’s My Line? appearances. And he was far from the lone big leaguer to be seen on the show; before the end of 1950, on June 21 and August 16, Dizzy Dean and Jackie Robinson were “mystery guests.” During the show’s early years, a lengthy roster of the ballplayers guesting on What’s My Line? were affiliated with the New York nines. If non-New York players appeared – on June 24, 1956, 11 Cincinnati Reds comprised the “mystery guest” – it was because they were passing through town. On that date, the Reds had battled the Dodgers in an Ebbets Field twin bill.2

Since the medium’s earliest years, baseball has had a presence in a range of TV series episodes. Some showcase top Tinseltown talent. In 1956 – almost two decades before its screen version – “Bang the Drum Slowly” was presented “live from New York” as a segment of The United States Steel Hour (1953-1963). Paul Newman, then a budding Hollywood superstar, plays Henry Wiggen, “left-hand pitcher for the New York Mammoths” who won 26 games in ’52, while Albert Salmi and George Peppard are cast as Bruce Pearson and Piney Woods.3 The year before, the legendary John Ford helmed “Rookie of the Year,” broadcast on Screen Directors Playhouse (1955-1956); the teleplay involves Mike Cronin (John Wayne), a cynical small-town sportswriter who determines that a hot young New York Yankee rookie is the son of an ex-star who was thrown out of baseball for taking a bribe.4Then in 1962, Ford directed “Flashing Spikes,” an episode of Alcoa Premiere (1961-1963), which features James Stewart as Slim Conway, an ex-big leaguer wrongly banned from baseball for taking a bribe and accused of corrupting a young phenom. The program is “Presented by Fred Astaire,” who also narrates. Joining Stewart in the cast are Don Drysdale, playing a pitcher named Gomer – rest assured that his surname is not Pyle; Vin Scully as “The Announcer”; Art Passarella as “The Series Umpire”; Vern Stephens as “The 1st Baseball Player”; John Wayne’s son, Pat; and The Duke himself, billed as “Michael Morrison” and cast as “The Marine Sergeant.” (Wayne’s birthname was Marion Morrison.)5

“Flashing Spikes” is not the only teleplay in which real-life baseball personalities mix with actors. One example is “High Pitch,” an original mini-musical a là Damn Yankees that was broadcast in 1955 on Shower of Stars (1954-1958). I Love Lucy’s William Frawley, himself a famed baseball fan-atic, plays Gabby Mullins, manager of the Brooklyn Hooligans, a perennial last-place nine. Vivian Vance, who was Ethel to Frawley’s Fred Mertz, is Mullins’s wife. In the opening scene, a ballgame is being broadcast on television. Mel Allen, the show’s “special guest,” is the announcer. Coming to the plate is Ted Warren (Tony Martin), described by Allen as “the big slugger of the Spartans who once played for the Hooligans.” Warren promptly homers, and Mel promptly interviews Mullins.6

(Frawley brings his love of the sport to Fred Mertz, his I Love Lucy character. In “Lucy Is Enceinte,” the classic 1952 episode in which Lucy tells Ricky she is pregnant, Fred enters with a ball, bat, glove, and New York Yankees cap. He hands the latter three to Lucy, “for my godson.” Regarding the baseball, he adds: “And wait’ll you see the name on this. That’s the name of the best ballplayer the Yankees ever had.” “Uh, Spalding,” Lucy blurts out, after glancing at it. “C’mon, honey, turn it around,” Fred instructs. “Oh, Joe DiMaggio,” Lucy declares. “You betcha,” Fred responds, taking a mock batting stance. “Ol’ Joltin’ Joe himself.” Indeed, Frawley might have suggested this dialogue, as he and the Yankee Clipper were close friends.)7

The Pride of the Yankees (1942), starring Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig, is perhaps the most beloved baseball film of its era. But it is not the lone Hollywood property to spotlight Gehrig, his wife, Eleanor, and the disease that doomed him. Over two decades before A Love Affair: The Eleanor and Lou Gehrig Story (1977), a made-for-TV movie, another Gehrig teleplay – “The Lou Gehrig Story” – was an episode of Climax! (1954-1958). The program, which dates from 1956, bookends footage of the real Gehrig on July 4, 1939, the day in which he was honored at Yankee Stadium, with images of him at bat and in the field. Wendell Corey plays Gehrig, Jean Hagen is Eleanor, and the story spotlights their deep affection. “I just can’t hit anymore,” the perplexed Yankee tells his worried wife. “If I can’t play ball anymore … I’ll learn to do something else.” Ellie tells him, “You’re it. You’re the works…,” adding that it “hasn’t got anything to do with your batting average. …” But Lou is obsessed with breaking out of his slump and endlessly watches footage of him homering off Dizzy Dean. A hardnosed – and fictional – young Yankee named Rusty (Russell Johnson) lambastes him for his play, insisting that “the great Gehrig” be benched, while Bill Dickey (Harry Carey Jr.), his best friend and teammate, steadfastly supports him. However, after not feeling pain after accidentally pouring hot coffee over his hand and then tripping and falling, it is clear that Gehrig is battling more than a batting slump.8

One of the more intriguing early baseball episodes – this one featuring no ballplaying celebrity guests – is “The Mighty Casey,” a 1960 segment of The Twilight Zone (1959-1964). “The Mighty Casey” is the story of the lowly Hoboken Zephyrs, a once-upon-a-time major-league nine whose ballyard, as host-narrator Rod Serling explains, has become a “mausoleum of memories.” “We’re back in time now,” he adds, and the setting is tryout day in Hoboken, New Jersey, where one of the wannabes is Casey, a left-handed hurler. What makes Casey special is that he is not human; he is a robot who, as his creator notes, has “only been in existence three weeks.” Casey is signed by the Zephyrs and promptly fans 18 batters and pitches a three-hit shutout. But upon his being beaned, a doctor determines that he has no heart. In order to qualify as a pro, Casey is operated on and given one. But with a heart, he no longer is mighty: He is just another ordinary athlete who has difficulty fanning opposing hitters. Despite its fantasy element, “The Mighty Casey” features references to real baseball stars. Casey is not intimidated by Joe DiMaggio because he has never heard of Joe D. The robot is described as having the talent of “three Bob Fellers.” The baseball commissioner declares that Zephyrs opponents will be angered by Casey’s origin, noting that “the other clubs ’er gonna scream bloody murder. I could just hear Durocher now.”9

The episode was tinged by tragedy. Paul Douglas originally played “Mouth” McGarry, the Zephyrs skipper who is described by his general manager as possessing the “widest mouth in either league.” Elements of “The Mighty Casey” are reminiscent of Douglas’s two baseball films: It Happens Every Spring (1949), involving a college professor-turned pitcher (played by Ray Milland) whose Casey-like hurling wins ballgames; and the original Angels in the Outfield (1951), in which Douglas plays a McGarry-like manager. However, right after filming the show, Douglas died of a heart attack. He looked perpetually haggard in his scenes and, as Serling stated, “We were watching him literally die in front of us.” So the episode was reshot, with Jack Warden replacing Douglas.10

A couple of years before the filming of “The Mighty Casey,” the Brooklyn Dodgers had relocated to Los Angeles – and the team now was a stone’s throw from California’s then-burgeoning television production. Granted, non-Dodger names kept popping up on TV shows: Mickey Mantle, for example, appeared as himself in “Second Base Steele,” a 1984 episode of Remington Steele (1982-1987), and “The Field,” a 1989 episode of the Bob Uecker sitcom Mr. Belvedere (1985-1990); and in 1971 even guested on Hee Haw (1969-1997), the country-oriented comedy-variety show. And Jason Giambi played a New York cabdriver in The Bronx Is Burning (2007), an eight-episode ESPN miniseries depicting the 1977 New York Yankees season. But given the opening of the West to big-league baseball, a host of Los Angeles Dodgers began popping up on TV series. (Dodgers players en masse are seen in a number of films, including 1958’s The Geisha Boy, a Jerry Lewis comedy, and 1962’s Experiment in Terror, a thriller. The Geisha Boy features an exhibition game between the Dodgers and a Japanese nine, with Pee Wee Reese, Charlie Neal, Jim Gilliam, Gil Hodges, Gino Cimoli, Carl Furillo, Duke Snider, Carl Erskine, and Johnny Roseboro appearing in brief color clips. The finale of Experiment in Terror is set in Candlestick Park, where the Dodgers are battling the San Francisco Giants. During the game there are expressive close-ups of Don Drysdale taking signs from his catcher, nodding, winding up, and pitching. Giant Harvey Kuenn is seen cracking a double; he is followed to the plate by Felipe Alou. Dodger Wally Moon appears in close-up as he clutches a bat. He beats out an infield hit to shortstop Jose Pagan and Vin Scully describes the ensuring rhubarb, whose participants include Giants Mike McCormick, Ed Bailey, Willie McCovey, and Joe Amalfitano.)

Among the biggest Dodgers names to appear on the small screen is the aforementioned Don Drysdale. Not all his TV appearances were in acting roles. He and his then-bride Ginger (whom he divorced in 1982) are seen in a February 26, 1959, episode of You Bet Your Life (1950-1961). “In case there may be some isolated listener who has never heard of Don Drysdale, he just happens to be one of the greatest pitchers in the world today and he happens to be playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers” was how George Fenneman, the show’s announcer, introduced the 22-year-old pitcher to host Groucho Marx. As the newlyweds kibitz with Groucho, Ginger recalls first meeting Don and how they were engaged 17 days later.11

That November Drysdale and two “impostors” were guests on To Tell the Truth (1956-1968). “One of these men is a pitcher for the world champion Los Angeles Dodgers,” an announcer informs the audience; in this pre-mass-media era, it was logical that none but the most diehard baseball fan would immediately recognize the ballplayer. But Don Ameche, one of the four panelists, did, and disqualified himself. The others – Monique Van Vooren, Kitty Carlisle, and Tom Poston – all correctly selected the real Drysdale, with Carlisle (who admitted that she never had seen a baseball game) explaining her pick by declaring that he somehow “has that baseball look.”12

On occasion Drysdale was joined by Dodgers teammates. Five of them – Ron Perranoski, Tommy Davis, Willie Davis, Frank Howard, and Moose Skowron – appeared with him in a 1964 broadcast of The Joey Bishop Show (1961-1965). The ballplayers harmonize as they perform a Sammy Cahn-written parody of Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen’s “High Hopes,” with Drysdale singing lead. He begins, “When they all said that the Dodgers was dead, that’s when we came to life…” And the words “high hopes” are replaced first by “Koufax” and then by “Drysdale.”13 (The previous year Drysdale even recorded a pair of ballads for Reprise records. Their titles were “Give Her Love” and “One Love.”)

Indeed, in the early 1960s, Drysdale was being primed for show-biz stardom. He was good-looking, with a fine screen presence. At the time, Eddie Cantor was featured on a radio program, appropriately titled, Ask Eddie Cantor, in which he answered questions submitted by listeners. One of them, on the June 14, 1961, broadcast, was: “Is Don Drysdale the best-looking Dodger?”14The pitcher began appearing on TV series, particularly in such westerns as Lawman (1958-1962), in a 1960 episode titled “The Hardcase”; The Rifleman (1958-1963), which starred ex-ballplayer-turned actor Chuck Connors, in “Skull,” a 1962 episode; and Cowboy in Africa (1967-1968), also featuring Connors, in a 1968 episode titled “Search and Destroy.” In “Millionaire Larry Maxwell,” a 1960 episode of The Millionaire (1955-1960), Drysdale’s character is named Eddie Cano; in “The Spitball Kid,” a baseball-related 1969 episode of Then Came Bronson (1969-1970), he is Art Gilroy, a scout; in “The Big Game,” a 1969 episode of The Flying Nun (1967-1970) that involved a convent baseball team, Drysdale is billed as “The Umpire” while Willie Davis is “The Manager.”

Most prominently, Drysdale guest-starred as himself in a host of baseball-linked scenarios, from “Who’s on First,” a 1963 episode of Our Man Higgins (1962-1963), to “The Two-Hundred-Mile-an-Hour Fast Ball,” a 1981 episode of The Greatest American Hero (1981-1983). Between 1962 and 1964, he made four appearances on The Donna Reed Show (1958-1966), with three featuring baseball-themed titles: “The Man in the Mask”; “My Son the Catcher” (with Willie Mays); and “Play Ball”; the fourth is titled “All These Dreams.” “Play Ball,” which also features Mays and Leo Durocher, involves autographed baseballs to be sold for charity and a ballgame between hospital personnel and a college freshman nine. Along the way, Durocher gets to comically trash umpires. Beyond its nostalgia quotient, “Play Ball” is a mirror of its era. Here, adult males – even doctors – are collectively out of shape; exercise and ballplaying only are reserved for the young. Meanwhile, women are collectively baseball-illiterate.15

In a Leave It to Beaver (1957-1963) episode from 1962 titled “Long Distance Call,” the Mayfield Press headline is “Don Drysdale’s Homer Beats Giants”; this inspires The Beaver (Jerry Mathers) and a couple of his pals to place – what else? –a long-distance phone call to Drysdale, “their favorite baseball player,” at Dodger Stadium. They pool their pocket change, and are convinced that the cost only will be a dollar, but a mini-crisis results as the total mounts. But The Beaver does get to ask Drysdale to autograph his glove. It’s a Warren Spahn model, but the ever-amenable Dodger tells him, “Well, I’ll autograph it anyway.”16Then in “The Dropout,” a 1970 episode of The Brady Bunch (1969-1974), Mike Brady (Robert Reed) is designing Drysdale’s new house. “You know, baseball’s been real good to me,” the pitcher observes. Mike invites the ballplayer home to meet his boys, resulting in son Greg (Barry Williams) becoming convinced that his future is as a big-league hurler.17

Coming in a strong second to Drysdale as a TV guest star is Leo Durocher, who coached the Dodgers between 1961 and 1964. In “The Clampetts and the Dodgers,” a 1963 episode of The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971), bank president Milburn Drysdale – who is no relation to Don, but the name of one of the show’s supporting characters – sets up a golf game in which Jed (Buddy Ebsen) and Jethro (Max Baer Jr.) will play with Durocher (whose surname the Clampetts constantly pronounce as “Doooorocher”). But of course, the boys think they are going hunting, where they will be “shooting golfs” and “dodging golfs.” Jethro declares, of Durocher, “Miss Jane says he’s a famous dodger.” Adds Elly May (Donna Douglas), “He’s so good, he coaches all other dodgers.” Leo then is seen at Dodger Stadium mentoring real ballplayers during batting practice, and a pitching prospect confuses bank president Drysdale with pitching star Drysdale. Eventually Jed and Jethro meet Durocher at the Wilshire Country Club, where they are mistaken for caddies. But Jethro’s talent for tossing a baseball (which he thinks is “another one of them big eggs”) convinces Leo that he has stumbled upon a legitimate prospect, whom he describes as “a one-man pitching staff” who possesses “the greatest arm since Satchel Paige.” Actor Wally Cassell appears as Dodgers general manager Buzzy Bavasi; when Jethro declares that he wants no money for throwing baseballs, the GM responds, “O’Malley will love you.” But Jethro never will make the majors: In order to throw a baseball at a lightning-fast speed, he must smear his hand with possum fat.18

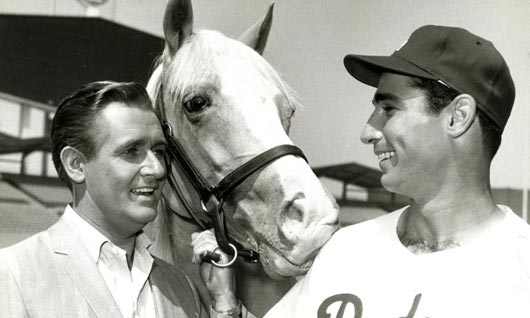

Sandy Koufax with Alan Young, the star of TV ’s Mr. Ed, and Mister Ed himself. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

“Leo Durocher Meets Mister Ed,” a 1963 episode of Mister Ed (1958-1966), opens with the title character, a talking horse, wearing a Los Angeles Dodgers cap; plus, his stable is crammed with team memorabilia. A Dodgers game, announced by Vin Scully, is on television, and the nine is in a terrible slump. “Those bums should have stayed in Brooklyn,” a flustered Mister Ed declares. Wilbur (Alan Young), Mister Ed’s owner, is convinced that Leo the Lip is “going to want some tips on how to help his players,” and the horse is all too willing to offer them. How did Mister Ed come to be such an expert? Well, it is revealed that, once upon a time, he “played in the Pony League.” Wilbur and Mister Ed end up at Dodger Stadium, where they meet Willie Davis, John Roseboro, Moose Skowron, and “the old strikeout king, Sandy Koufax.” And of course, there is Leo Durocher. Upon being introduced to the horse, Leo quips, “For a minute, I thought it was Casey Stengel.” Sandy then pitches batting practice to Davis and Roseboro, with Mister Ed offering his expertise. Plus, with bat in mouth, the horse hits against Koufax and, via some crafty editing, smashes a homer. Mister Ed asks Wilbur if the Dodgers might sign him as a player. “A horse on the Dodgers!” is his incredulous response. “Well, why not,” Mister Ed quips. “They already got a Moose.”19

Then in “Herman the Rookie,” a 1965 episode of The Munsters (1964-1966), Herman Munster (Fred Gwynne) hits fungoes in a park while mentoring Eddie, his young son. One travels eight blocks and lands on the head of Durocher just after he observes, “If we can come up with a power hitter, I mean a guy (who) can hit the long ball, I think my old club is a cinch to win the pennant.” Durocher seeks out Herman, who excitedly shows up for a Dodgers tryout. The balls he belts are lightning-fast and lightning-far and, in a then-topical reference, Durocher notes, “I don’t know whether to sign him with the Dodgers or send him to Vietnam.” However, while in the field, Herman crashes through a fence and throws a ball so hard that it explodes – and he is not signed because, as he explains, “Mr. O’Malley said it would cost him $75,000 to put the Dodger Stadium back in shape every time I played. … And they said the insurance companies wouldn’t allow the players on the same field with me.”20

Featured in “Herman the Rookie” is a reference to the Dodgers’ former home city. Upon entering the Munsters’ creepy abode, Durocher quips, “I’ve never seen a place like this in my whole life. Not even in Brooklyn.”21 Briefly appearing as a catcher is Ken Hunt, the stepfather of series regular Butch Patrick, who plays Eddie. Between 1959 and 1964, Hunt appeared in 310 major-league games with the Yankees, Angels, and Senators. None were with the Dodgers.

As the decades passed, the Drysdales and Durochers of the sport need not have guested on a sitcom for there to be a baseball motif. In “Bang the Drum, Stanley,” a 1988 episode of The Golden Girls (1985-1992), Dorothy Zbornak (Beatrice Arthur) is visited by Stanley (Herb Edelman), her lying, cheating ex-husband. “I was out taking a drive listening to the Dodgers on the radio and I got a sudden urge to see a ballgame,” he tells Dorothy. And he adds, “Dorothy, I was thinking about us. Good old days back in Brooklyn. Ebbets Field. Those long summer nights sitting in the bleachers eating hot dogs, rooting for the Dodgers and kissing passionately between innings.” But Dorothy reminds Stanley that they never were together at Ebbets Field. Stanley’s faux reminiscing is a plot to sweet-talk Dorothy into lending him some money.22

Then in “Where’s Charlie,” a 1991 episode, bawdy Blanche Devereaux (Rue McClanahan) begins dating – and coaching – Stevie (Tim Thomerson), a professional ballplayer. ”Oh, you got Blanche’s number from the wall in the dugout,” quips Sophia (Estelle Getty), who is Dorothy’s mother and queen of the one-liners. Blanche then equates baseball with sex. “Now look, you have to discover the sensuality of baseball,” she tells Stevie. “(There are) many, many, many similarities between baseball and making love. The mental preparation. The rush of adrenaline. The unspecified duration of the game.” Sophia chimes in, “And you should hear the cheers coming from Blanche’s room on Old Timers Day!” This is followed by a Bull Durham reference.23

Across the decades, the central characters on hit TV series have been lawyers, doctors, cops … rarely have they been ballplayers. And when baseball has been featured, the shows usually are flops. The Bad News Bears and A League of Their Own, both hit movies, were short-lived TV series (in 1979-1980 and 1993 respectively). The one-episode presence of Johnny Bench in Bears and Doug Harvey and Ken Brett in League had no impact on the ratings.

How many viewers remember Hardball (1994), spotlighting the Pioneers, an inept ballclub? A cameo appearance by Barry Bonds couldn’t save this one. Or A Whole New Ballgame (1995), with Corbin Bernsen as a ballplayer-turned-sportscaster? Or Clubhouse (2004-2005), about a 16-year-old New York Empires batboy? Ron Darling’s one-episode presence as an announcer was no ratings boost. More successful was HBO’s Eastbound & Dawn (2009-2013), featuring Danny McBride as Kenny Powers, a burned-out ex-big leaguer-turned physical-education teacher. One promising entry is Pitch, which premiered in 2016 and spotlights Genevieve “Ginny” Baker (Kylie Bunbury), the first woman to make the majors, hurling for the San Diego Padres. However, two failed shows that remain worthy of scrutiny are Ball Four (1976), inspired by Jim Bouton’s landmark book, with Bouton himself starring as Jim Barton, ballplayer-turned-Sports Illustrated writer; and Bay City Blues (1983), centering on the Bluebirds, a fictional minor-league nine from Bay City, California, that was created by Steven Bochko and Jeffrey Lewis, of Hill Street Blues fame.

Nonetheless, baseball-on-the-small-screen occasionally has resonated with viewers. One obvious example is Cheers (1982-1993), the iconic sitcom featuring Ted Danson as Sam Malone, ex-Red Sox reliever whose career was wrecked by drink. The sitcom primarily is set not in the Fenway environs but in the Boston bar that Sam had purchased; Ernie Pantusso (Nicholas Colasanto), Malone’s bartender, was his former coach. Still, baseball sporadically made its way into Cheers storylines. In “Breaking In Is Hard to Do,” from 1990, arbiter Doug Aducci (Clive Rosengren) enters Cheers. Sam calls him “one of the best damn umpires in the American League,” but the two immediately immerse themselves in an on-field-style brawl as the ex-hurler recalls a game between the Red Sox and Yankees. It is the ninth inning. The Sox are down by a run. Malone is on the mound, and he angrily declares that Aducci “calls ball four on Munson. Next guy up is Chambliss, knocks one right out of the park.”24And in “Pitch It Again, Sam,” a 1991 episode, New York Yankee Dutch Kincaid (Michael Fairman) beseeches Sam to pitch to him on the team’s “Dutch Kincaid Day.” His reasoning: He belted a homer on practically every occasion in which he faced Sam, and he was hoping for a repeat performance.25

On occasion real Massachusetts celebrities appear on Cheers as themselves, from John Kerry and Michael Dukakis to Kevin McHale. Two are Boston Red Sox. In 1983’s “Now Pitching, Sam Malone” – a title with a double meaning – Luis Tiant is seen in a TV ad hawking a beer but flubs the tagline “You don’t feel full with Fields, you just feel fine.”26Then in “Bar Wars,” from 1988, Wade Boggs walks into Cheers and introduces himself. “Yeah, pal, and I’m Babe Ruth,” responds disbelieving bar regular Norm (George Wendt). “And I’m Dizzy Dean,” quips Cliff (John Ratzenberger). But the punchline belongs to Woody (Woody Harrelson), the ever-clueless bartender, when he chimes in, “I’m Woody Boyd.”27

The Simpsons (1989- ) occasionally has spotlighted the sport. In “Homer at the Bat,” broadcast in 1992, Homer leads the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant softball nine into the league finals. Mr. Burns, a Steinbrenner-like tyrant, rids the team of its employee-players; his ringer-substitutes, who all recorded their own voices, are Darryl Strawberry, Roger Clemens, Don Mattingly, Ozzie Smith, Wade Boggs, Ken Griffey Jr., Jose Canseco, Steve Sax, and Mike Scioscia.28

Another sitcom with knowing baseball references is Seinfeld (1989-1998), in which George Costanza (Jason Alexander) spends several seasons as a Yankees employee and comically tussles with “Big Stein,” otherwise known as George Steinbrenner (voiced by Larry David). In “The Opposite,” a 1994 episode, job applicant Costanza first mixes with potential employer Steinbrenner and The Boss politely declares, “Nice to meet you.” Costanza tells him, with the Yankee Stadium field seen through a window, “Well, I wish I could say the same, but I must say, with all due respect, I find it very hard to see the logic behind some of the moves you have made with this fine organization. In the past 20 years, you have caused myself and the city of New York a good deal of distress as we have watched you take our beloved Yankees and reduced them to a laughingstock, all for the glorification of your massive ego.” To which Steinbrenner responds, “Hire this man!”29

Jerry Seinfeld is a noted New York Mets fan; in “The New Friend,” a two-part episode also called “The Boyfriend, Part 1” and “The Boyfriend, Part 2” that aired in 1992, his character meets and befriends Keith Hernandez, the ex-Met first sacker. Jerry and his pals are in awe of Keith, but complications arise when Hernandez begins dating Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus). She tells Jerry, “I’ve never seen you jealous before.” And Jerry responds, “Well, you’re not even a fan. I was at Game Six – you didn’t even watch it.”30

An alleged “spitting incident” also plays a role in the scenario. The date was June 14, 1987, and Newman (Wayne Knight) recalls that he and Kramer (Michael Richards) were “enjoying a beautiful afternoon in the right-field stands when a crucial Hernandez error (led) to a five-run Phillies ninth. Cost the Mets the game.” Kramer chimes in, “Our day was ruined. There was a lot of people, you know, they were waiting by the players’ parking lot. Now we’re coming down the ramp. … Newman was in front of me. Keith was coming toward us (and) as he passes Newman turns and says, ‘Nice game pretty boy.’ Keith continued past us up the ramp.” And Newman continues, “A second later, something happened that changed us in a deep and profound way from that day forward.” “What was it?” Elaine wonders. Kramer answers her: “He spit on us … and I screamed out, ‘I’m hit!’” Newman adds, “Then I turned and the spit (ricocheted off) him and it hit me.” But Jerry is a nonbeliever, explaining that “the immutable laws of physics contradict the whole premise of your account.” Eventually, it is revealed that Mets reliever Roger McDowell was the culprit.31 Hernandez and George Steinbrenner also reappear in the show’s final episode; they attend the trial of Jerry, Costanza, Kramer, and Elaine, who are accused of cracking jokes about and filming an overweight robbery victim. The “baseball insider” references continue, as Frank Costanza (Jerry Stiller), George’s father, asks Steinbrenner, “How could you give $12 million to Hideki Irabu?”32

In terms of popularity, The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-1966) is the Seinfeld of its era. Dick Van Dyke, Mary Tyler Moore, Rose Marie, Morey Amsterdam, and Larry Mathews play Rob and Laura Petrie, Sally Rogers, Buddy Sorrell, and Ritchie Petrie. Carl Reiner, the show’s creator, occasionally appears as Alan Brady, the egomaniacal TV star who employs Rob, Sally, and Buddy as comedy writers. However, the show’s unsold 1959 pilot, titled Head of the Family, features a completely different cast. Reiner himself is Rob (whose surname is pronounced “Peetrie”); Barbara Britton, Sylvia Miles, Morty Gunty, and Gary Morgan play Laura, Sally, Buddy, and Ritchie, while the Brady character is named “Alan Sturdy.” And the storyline is New York baseball-centric. There are casual references to Casey Stengel and Hank Bauer, and the plot centers on 6-year-old Ritchie’s complaining to Laura that “daddy never plays baseball with me…” He follows up with a question: “Why couldn’t you marry Mickey Mantle? … Well, I love Mickey. Don’t you love Mickey?” (Toronto fans might chuckle over the name of the street on which the Petries’ suburban abode is located. It is neither Lou Gehrig Lane nor Bronx Bomber Byway but Blue Jay Blvd.!) 33

And finally, a show that is not baseball-centric still might offer a knowing peek into the pressures and realities of ballplayers, not to mention the essence of the sport. In an episode on Lou Grant (1977-1982) titled “Catch” – surely, a name with a double meaning – Los Angeles Tribune reporter Billie Newman (Linda Kelsey) meets and falls for Ted McCovey (Cliff Potts), who is introduced as a Los Angeles Dodgers “catcher who was third-string until they traded him to the Bay Area last winter.” Ted also has been playing for “14 years, 10 in the majors.” Not surprisingly, the first time he is mentioned, he is mistaken for Willie McCovey. Soon enough, Ted is put on irrevocable waivers by the Giants. “Kid they called up to replace me was battin’ .385 in Triple A,” he explains, adding, “You know what baseball done for me? Treated me like a kid the past 14 years and now suddenly they’re tellin’ me I’m an old man.” But there is a happy ending here, as Ted takes a job as a Dodgers scout.34

“Catch” and “Wedding,” its follow-up episode, both aired in 1981 – and both feature references that place the storyline in the proper timeframe. In “Wedding,” Ted is about to propose to an unsuspecting Billie. Before he can do so, she asks him, “Does it have something to do with baseball? Did you find another Valenzuela?” Billie also thinks that ERA stands for “Equal Rights Amendment,” which she hopes will pass, and not “Earned Run Average.” Both episodes are peppered with baseball links. Ted is convinced that marriage to Billie will be fruitful because of his “catcher’s instinct.” And the preacher who marries them is an ex-ballplayer who traded “the horsehide for the cloth.”35

The “Catch” teleplay also offers a potent explanation of why baseball matters. As they spend time together, Billie – who is no baseball fan – complains that the game is “so slow.” “It’s like saying your life is slow,” Ted responds. “What does that mean? There’s so much going on (in baseball). Every pitch is another decision. Where to play the hitter. What to throw him. (What happens) if the runner goes on the pitch. Who’s on deck? You take a chance (or) you play the percentages. There’s a thousand decisions in a game. … Probabilities. Statistics. … The mutations are infinite. A game could go on forever. … I’ve played 5,500 games, give or take, since Little League. I’ve watched a couple thousand more. Never played the same game twice. And every one, a situation comes up (that) I’d ever seen before.”36

ROB EDELMAN is the author of Great Baseball Films and Baseball on the Web (which Amazon.com cited as a Top 10 Internet book), and is a frequent contributor to Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game. He offers film commentary on WAMC Northeast Public Radio and is a longtime Contributing Editor of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide and other Maltin publications. With his wife, Audrey Kupferberg, he has coauthored Meet the Mertzes, a double biography of Vivian Vance and super-baseball fan William Frawley, and Matthau: A Life. His byline has appeared in Total Baseball, The Total Baseball Catalog, Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond, NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, The Baseball Research Journal, and histories of the 1918 Boston Red Sox, 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers, 1947 New York Yankees, and 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates. He is the author of a baseball film essay for the Kino International DVD Reel Baseball: Baseball Films from the Silent Era, 1899- 1926; is an interviewee on several documentaries on the director’s cut DVD of The Natural; was the keynote speaker at the 23rd Annual NINE Spring Training Conference; and teaches film history courses at the University at Albany (SUNY).

Notes

1 espn.go.com/mlb/story/_/id/10731028/mlb-baseball-miss-david-letterman.

2 Rob Edelman. “What’s My Line? and Baseball,” The Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2014: 36.

3 youtube.com/watch?v=rPc9keZ1cl0.

4 free-classic-tv-shows.com/Drama/Screen-Directors-Playhouse/1955-12-07-s1-ep10-Rookie-of-the-Year/index.php.

5 youtube.com/watch?v=Xmzknb3hWAQ.

6 Rob Edelman and Audrey Kupferberg, Meet the Mertzes (Los Angeles: Renaissance Books, 1999), 149, 153.

7 Edelman and Kupferberg, 173.

8 youtube.com/watch?v=fsuwx8xVpuU.

9 youtube.com/watch?v=N1Qs24BfR5I.

10 twilightzonevortex.blogspot.com/2012/07/mighty-casey.html.

11 youtube.com/watch?v=qzhVOKqlIDc.

12 youtube.com/watch?v=rKld2Z_X-C0.

13 youtube.com/watch?v=8nwCYqkoDeM.

14 youtube.com/watch?v=iApcQ2zerc4.

15 youtube.com/watch?v=YaDLOtLoFuc.

16 youtube.com/watch?v=srLiKccFFRw.

17 hulu.com/watch/633526.

18 youtube.com/watch?v=-288A4pp6VI.

19 youtube.com/watch?v=uAY58hsMVnI.

20 youtube.com/watch?v=cR9HDJW9Jmk.

21 Ibid.

22 youtube.com/watch?v=Uy-AkWsUqVw.

23 youtube.com/watch?v=YMBgWl1rgY8.

24 youtube.com/watch?v=idBHtrs-Xy4.

25 imdb.com/title/tt0539831/.

26 avclub.com/tvclub/cheers-now-pitching-sam-malonelet-me-count-the-way-67192.

27 youtube.com/watch?v=979ArlkjFck.

28 See the SABR book Nuclear-Powered Baseball (Phoenix: SABR, 2016).

29 youtube.com/watch?v=vWCGs27_xPI.

30 seinfeldscripts.com/TheBoyfriend1.htm.

31 Marissa Payne, “And the Best Sports of All Time on ‘Seinfeld’ Was…,” Washington Post, July 3, 2014.

32 youtube.com/watch?v=dzeuvZc1KI8.

33 youtube.com/watch?v=Ll22fkwOhH4; youtube.com/watch?v=wvdzwsTj9_4.

34 youtube.com/watch?v=ozeeyoJyOmo.

35 youtube.com/watch?v=CoZC5rvqHRc.

36 youtube.com/watch?v=ozeeyoJyOmo.