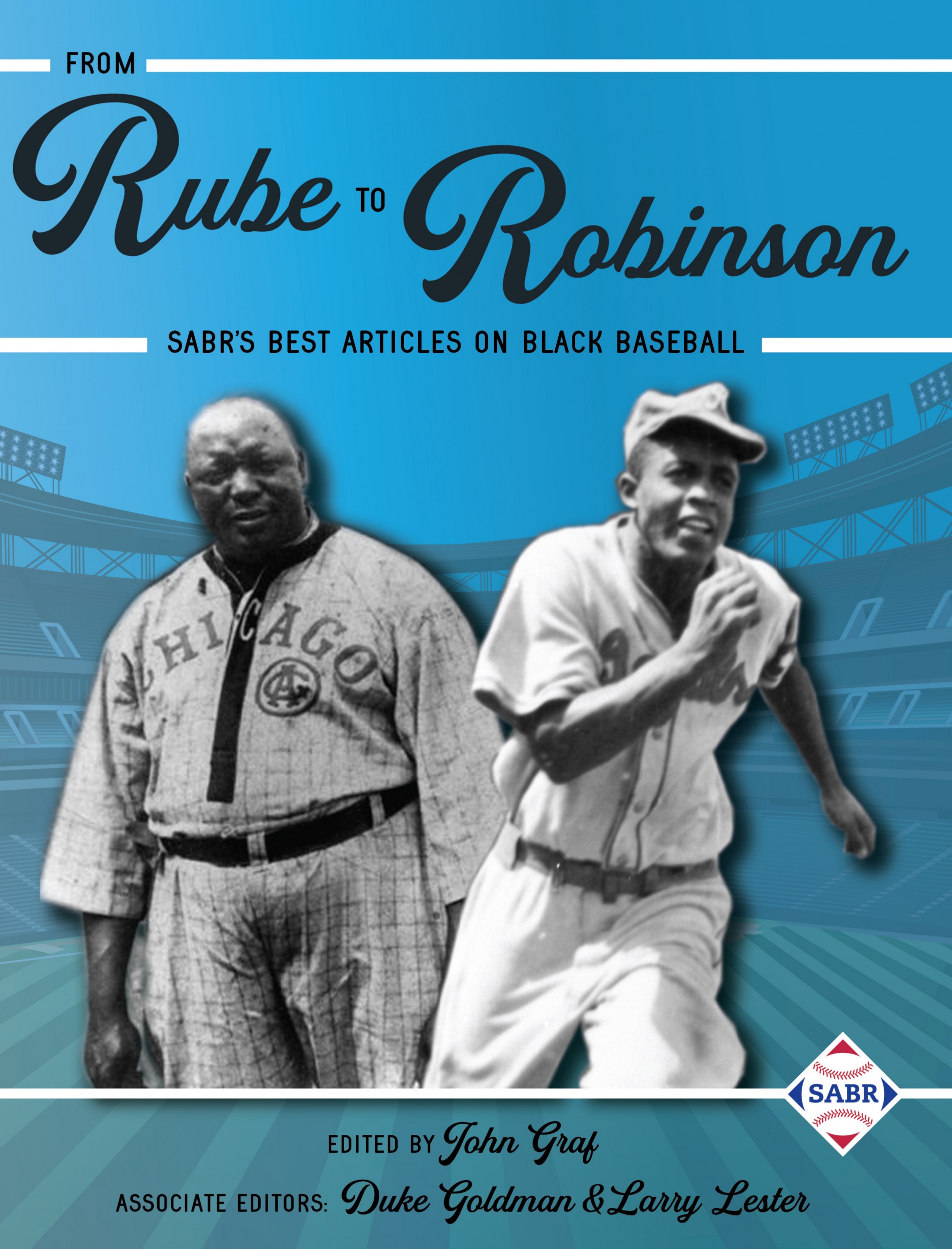

Introduction: From Rube to Robinson

This article was written by John Graf

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (2021)

Click here to download your free e-book edition or save 50% on the paperback of From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball, edited by John Graf (SABR, 2021)

It almost goes without saying, that were it not for the Negro Leagues, modern professional baseball would be in a much different place.

It almost goes without saying, that were it not for the Negro Leagues, modern professional baseball would be in a much different place.

A modest case in point: Years after his retirement, former major leaguer Jerry Kenney was asked by a sportswriter in his boyhood proving ground of Beloit, Wisconsin, “What if your pro baseball career had happened, say 15 or 20 years later, after free agency and endorsement deals turned the sport into a mega-dollar business?” Kenney, who patrolled the infield and outfield for the New York Yankees and Cleveland Indians from 1967 until 1973, replied: “I think more about what it would have been like if it had been 15 or 20 years earlier, before Jackie Robinson came along. I wouldn’t have had a career.”1

Certainly, had it not been for Robinson’s breaking White baseball’s color line in 1946 in the International League with Montreal and the following season with the National League Brooklyn Dodgers, Kenney’s career, and those of countless others, would have been very different indeed. And just as certainly, had it not been for his predecessors in the Negro Leagues, Robinson’s own career trajectory would not have been the same. And had it not been for Andrew “Rube” Foster, the founder of the Negro National League, those predecessors would have found their circumstances quite different as well.

In his book The Heritage, journalist Howard Bryant illustrates a capsule history of Black baseball through a conversation he had with famed manager Dusty Baker, a one-time protégé of Henry Aaron’s during the mid-1960s: “…I told him I could take him through the history of Black baseball, from 2017 back to 1920, the first days of the Negro Leagues, in just four handshakes, starting with his:

Dusty shook hands with Henry Aaron.

Henry shook hands with Jackie Robinson.

Jackie shook hands with Satchel Paige.

Satchel shook hands with Rube Foster.2

With apologies to Mr. Bryant, two more handshakes will take us all the way back to the beginning of Black professional baseball:

Rube Foster shook hands with Sol White.

Sol White shook hands with Bud Fowler.

With those handshakes in mind, this volume, From Rube to Robinson, aims to bring together the best Negro League baseball scholarship that the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) has ever produced, culled from its journals, Biography Project, and award-winning essays. The book begins with a nineteenth-century “Old Testament” prelude before delving into the launch of “the Ship” that was the Negro National League (NNL).

Todd Peterson’s “May the Best Man Win: The Black Ball Championships 1866–1923” inventories claims to baseball supremacy that preceded the Colored World Series competition that began in 1924. It touches on the teams, the player personnel, and other personalities in a skillful balance. A Sol White reference at the end of the article to the adage “may the best man [and now, reflecting changing times, woman] win” informs Peterson’s title. White’s appeal to fair play and equality was an early suggestion that, as Peterson has championed, the Negro Leagues were and are deserving of being called major leagues.3

The late Jerry Malloy, whose name graces SABR’s annual Negro League Conference, covers an early attempt at forming a Black baseball circuit in “The Pittsburgh Keystones and the 1887 Colored League.” Malloy points out that the short-lived league managed to garner the acceptance of the National Agreement of 1883 between the National League and the American Association, something no other Black organization was able to do.4

Jay Hurd profiles the great Sol White, a Hall of Fame player, manager, and executive who also made his mark writing about Black baseball and its challenges in a variety of venues. He penned the epochal Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball in 1907.5

Originally in SABR’s 1994 volume The Negro Leagues Book, Larry Lester’s updated “Rube Foster: Gem of a Man” describes the multi-faceted career of the legendary pitcher, manager, team owner, and guiding force behind the 1920 formation of the Negro National League. Foster’s teams outran and outwitted the opposition while the league provided an organizational infrastructure that strengthened Black baseball as a sporting and community institution.6

In “John Donaldson and Black Baseball in Minnesota,” Steven R. Hoffbeck and Peter Gorton tell the story of the legendary southpaw who amassed over 5,000 strikeouts and 400 wins during his long career and was part of the NNL’s 1920 inaugural season with the Kansas City Monarchs.7

Certainly deserving of headliner status is Oscar Charleston, considered by many to be the greatest Negro Leagues player ever, and deemed by author Bill James to be the fourth-best player of all time behind only Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Willie Mays.8 Jeremy Beer, whose Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player was chosen as SABR’s 2020 Seymour Medal Winner (which honors the best book of baseball history or biography published in the previous calendar year), examines and rebuts the common contention that Charleston was a villainous one-man wrecking crew in need of anger management in “Hothead: How the Oscar Charleston Myth Began.”9

Two seminal Negro Leagues researchers, Dick Clark — who sadly passed away in 2014 — and John Holway, provide a detailed snapshot of the 1921 NNL season that helps locate the campaign in larger context. A sidebar from the original 1985 article detailing SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee’s efforts to compile a statistical history has been added as a bonus.10

Harking back to Phil Lowry’s classic SABR publication Green Cathedrals, which compiled data on big league ballparks including Negro Leagues venues, are two articles that originally appeared in Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal.11 Both pieces were McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winners.

James Overmyer’s “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium” describes the tenant/landlord relationship of Negro Leagues teams with the New York Yankees during the 1930s and 40s. Overmyer subtitled his piece “The House that Ruth Built and Satchel Furnished (with Fans),” and utilized the financial records of the Yankees to make his case regarding the money-making prowess of Black baseball in the US’s most-populated city.12

Geri Driscoll Strecker’s “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field” is a cradle-to-grave biography of the Pittsburgh Crawfords’ stadium, covering — among other things — its location, ownership structure, architect, zoning process, brick façade and other park characteristics. The on-the-field performance of the Craws is touched upon and (spoiler alert) the story comes full circle as she describes the bulldozing of the site to make way for a public housing project.13

The final section of the book covers integration and the socio-economics of Black baseball. Leading off is Larry Lester’s masterful “Can You Read, Judge Landis?” which takes its name from a headline urging baseball’s high commissioner to assert his powers to end baseball’s color line. Lester refutes the contention that Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was blameless for the persistence of baseball’s segregation by focusing on the tireless efforts of the African American press and social activists who challenged baseball to make good on its promise of equal opportunity.14

Baseball’s official historian John Thorn and the late Jules Tygiel weigh in with “Jackie Robinson’s Signing: The Real, Untold Story,” which considers integration from a unique perspective. The color line that had been drawn in the 1880s was broken in the 1940s, but perhaps differently than previously thought.15

Japheth Knopp’s “Negro League Baseball, Black Community, and the Socio-Economic Impact of Integration” explores Kansas City as a case study in the effects of integration, asking: “…whether the manner in which desegregation occurred did in fact provide for increased economic and political freedoms for African Americans, and what social, fiscal, and communal assets may have been lost in the exchange.”16

Brian Carroll’s “Early Twentieth Century Heroes: Coverage of Negro League Baseball in the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender” studies the partnership of the African American press, local business communities, and baseball men such as Rube Foster to form the Negro National League and the later Eastern Colored League. Carroll cites newspaper coverage that considers ball club owners as community heroes until the 1930s, when the profiles of individual players were raised to star status from an inferior position. As Carroll describes, while some players were at times vilified as greedy by owners and reporters alike, other players such as Satchel Paige emerged who radiated excellence on the field and personality both on and off the diamond.17

Duke Goldman’s in-depth and meticulously referenced “The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball (NLB),” segues from baseball diamonds and uniforms to executive digs and business attire. The article concerns NLB’s winter and in-season meetings from the formation of a second Negro National League in 1933 through the last gasp of the Negro American League in 1962. Accounts of club and player transactions, bickering administrative factions, interleague squabbles, strained relationships between Black and White owners and promoters, and controversies over the “clowning” antics of some teams can be found here.18

Fittingly, the collection closes with longtime Black ball player and manager (and former SABR member) Gentleman Dave Malarcher’s poignant ode to Oscar Charleston, which first appeared in the 1978 Baseball Research Journal.19

The articles in From Rube to Robinson collectively assert that Black baseball’s history belongs directly alongside that of White or segregated baseball. Furthermore, the development of Black baseball as an institution was a part of the larger struggle for racial justice. The challenges of life on and off the field of a professional baseball player were experienced by Black players in ways unique to a population denied the promise of full emancipation. When White baseball shut down the promise of equal opportunity with the “gentlemen’s agreements” of the 1880s, it guaranteed that the lot of the Black ballplayer would be bound up with the attempt of the larger Black population trying to overcome the legacy of slavery.

Can there be any doubt this establishes the 100-year anniversary of the formation of the Negro National League in 1920, the first Black baseball organization to survive a full season, as a monumental development in both the history of baseball and the history of the United States as a whole? In commemoration of that anniversary, we present a collection of some of SABR’s “greatest hits.”

JOHN GRAF is a member of SABR’s Negro Leagues Research Committee who works for the Wisconsin State Assembly as an assistant clerk. He is a past winner of the Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference’s “Significa” (trivia) contest and has been a newspaper sportswriter and radio news reporter/announcer. Graf lives in Janesville, Wisconsin.

Notes

1 Jim Franz. “From Beloit to the Bronx,” Beloit Daily News, Stateline Legends series, 1995. 8-11.

2 Howard Bryant, The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism (Boston: Beacon Press. 2018), 239-240.

3 Todd Peterson, “May the Best Man Win: The Black Ball Championships, 1866–1923” in the Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2013, 7-24; Peterson, The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019).

4 Jerry Malloy, “The Pittsburgh Keystones and the 1887 Colored League” June 1995, in “Baseball in Pittsburgh,” SABR 25 Convention Journal.

5 Jay Hurd, ”Sol White,” SABR’s BioProject, 2011.

6 Larry Lester, “Andrew (Rube) Foster,” in The Negro Leagues Book¸ Dick Clark and Larry Lester, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1994), 40-41.

7 Steven R. Hoffbeck and Peter Gorton, “John Donaldson and Black Baseball in Minnesota,” The National Pastime, 2012, 117-122.

8 Bill James. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

9 Jeremy Beer, “Hothead: How the Oscar Charleston Myth Began,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2017, 5-15; Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln, Nebraska and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

10 Dick Clark and John B. Holway (1985),“Charleston No. 1 Star of 1921 Negro League,” Baseball Research Journal, 1985, 63-70.

11 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All Major League Ballparks (Fifth Edition: Phoenix, AZ: SABR, 2020).

12 James Overmyer, “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium,” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 7, 2014, 5-31.

13 Geri Driscoll Strecker, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark,” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 7, Fall 2009, 37-67.

14 Larry Lester, “Can You Read, Judge Landis?” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, Fall 2008, 57-82.

15 John Thorn and Jules Tygiel, “Jackie Robinson’s Signing: The Real, Untold Story” in The National Pastime #10, 1989, 1990, 7-12.

16 Japheth Knopp, “Negro League Baseball, Black Community, and The Socio-Economic Impact of Integration,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2016, 66-74.

17 Brian Carroll, “Early Twentieth Century Heroes: Coverage of Negro League Baseball in the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender” Journalism History, Vol. 32, No. 1, Spring 2006, 34-42.

18 Duke Goldman “The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” in The Winter Meetings: Baseball’s Business, Vol. 2, 1958-2016, Steve Weingarden and Bill Nowlin, eds., Marshall Adesman and Len Levin, associate eds., (Phoenix: SABR, 2017), 390-458.

19 Dave Malarcher, “Oscar Charleston,” Baseball Research Journal, 1978.

A Note on the Use of Language and Period Terminology

The words “Colored” or “Negro” or “organized” are employed throughout From Rube to Robinson as terms prevalent in common usage when the events described in this manuscript took place. Far from intending to make a political statement, some of our writers were hoping to recreate the spirit, attitude, and sentiment by using language that is no longer deemed appropriate.

In the mid-1920s, the eminent W.E.B. DuBois launched a letter-writing campaign to media outlets suggesting that the word “negro” be capitalized, as he found “the use of a small letter for the name of 12 million Americans and 200 million human beings a personal insult.” The New York Times adopted DuBois’ recommendation, as stated on their March 7, 1930, editorial page: “In our Style Book, Negro is now added to the list of words to be capitalized. It is not merely a typographical change; it is an act in recognition of racial respect for those who have been generations in the ‘lower case.’”

As we evolve socially and in scripture, I capitalize the words “Black” and “White” because I use them synonymously with other terms that are always capitalized, African American and European American. For years, publications like Ebony and Essence have always proudly capitalized the B, with many books and publications following suit this year.

In September 2019, President John Allen of the Brookings Institution announced in its style guide the organization would capitalize Black when used to reference census-defined Black or African American people, along with further revisions to a handful of other important racial and ethnic terms.

While there is no standard rule on whether references to race should capitalized, many writers rely on the Associated Press Stylebook that calls for capitalization of Black and White. Let’s note, starting with the 2000 Census, all racial and ethnic categories are capitalized — including White. It is now also officially SABR style to capitalize Black and White when referring to people in all SABR publications.

Let’s also note the term “organized” is problematic as it has become a dog whistle to imply that Negro League baseball was unorganized. This coded language taps into and reinforces stereotypes. The implication that the Black leagues were unorganized is unfounded. Black teams played under the same Official Baseball Rules, in the same stadiums, and ordered their uniforms, equipment, bats and baseballs from the same suppliers as the major league teams. The players had contracts, statistics were kept, and a schedule was printed in the newspapers. The infrastructure of the Black leagues and the White leagues were identical.

The adjective “organized” is a term based on the assumption that baseball historians possess subjectivity of what qualities define “organized.” Consequently, it is considered a judgmental term whose meaning is dependent on the user’s perspective, and thus best avoided. As we celebrate the Centennial of the Negro National League’s founding, let us be mindful of the words of National Baseball Hall of Fame first baseman, Walter “Buck” Leonard, “We were not unorganized, we were just unrecognized!”

The From Rube to Robinson anthology represents articles written during different periods of our literary evolution. With all due respect to the Eastern Colored League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the United Negro College Fund, our editors have taken some liberties in bringing this finished product in alignment with contemporary usage.

— Larry Lester

September 3, 2020