More Than Ballplayers: Baseball Players and Pursuit of the American Dream in the 1880s

This article was written by Marty Payne

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

This essay is intended as an exploratory survey of baseball players of the 1880s, what they did in the offseason, and how — or if — they planned for their future economic security. The purpose is to examine how the individuals of this era responded to the economic opportunities offered by their baseball careers and their pursuit of the ever-so-nebulous American Dream.

This essay is intended as an exploratory survey of baseball players of the 1880s, what they did in the offseason, and how — or if — they planned for their future economic security. The purpose is to examine how the individuals of this era responded to the economic opportunities offered by their baseball careers and their pursuit of the ever-so-nebulous American Dream.

In 1880 the organizing of professional clubs to determine a national champion was but nine years old and the concept was still evolving. Offseason and post-baseball employment, although not new ideas, were growing concerns as the number of seasonal professionals increased with the era’s proliferation of major and minor baseball leagues. Sources indicate players were willing to try many occupations and schemes in a changing and dynamic decade. The emphasis of this survey is on what players did when not playing baseball in order to discern any trends that might emerge. In this wide-ranging survey, the activities of obscure players become as important as those of the renowned.

The activities of 269 players of the 1880s were taken into consideration. While some material comes from the SABR Biography Project (BioProject) which includes valuable genealogical sources, much of the information is sourced from brief snippets in weekly periodicals and daily newspapers. Considering the latter source, the trends offered here should be viewed as anecdotal rather than hard data. It should also be noted that since many players pursued more than one activity and all activities were included, the sum of the percentages proffered are greater than the whole. Yet it is hoped that noting these activities and trends can help put baseball players of the 1880s into some historical and cultural context.

AN ERA OF CHANGE

The 1880s were a decade of transition in American history. Within nine months of July 14, 1881 — the date Billy the Kid was gunned down — the Earps and the Clantons fought it out at OK Corral and Jesse James was assassinated. Although these events were fodder for the dime novels and significant contributors to the growing mythology of the American “Wild West,” that frontier was already being tamed. By the beginning of the 1880s, both the Sioux and the Comanche had been effectively subdued, and later in the decade Geronimo and most Apache were captured and ignominiously shipped off to Florida, virtually ending Native American opposition to Anglo-American expansion.1 That growth was being spurred by the prolific extension of the railroads and telegraph into the Great Plains. In 1870 the estimated bison population was 5.5 million. By 1889 there were but 541 American bison remaining.2 The improvement and increased use of mass production farming equipment opened the middle of the continent to the last wave of settlers moving west. Within the span of many baseball players’ careers, the geographical void once called the Great American Desert was transformed into the Corn Belt. The already established American passions of real estate and mining speculation came with the mass migration. Financial and intellectual tycoons the likes of Rockefeller, Carnegie, Edison, and Tesla were making their impact. Implementation of technologies like the telephone, telegraph, electric lights, steel, and trolley systems were transforming the urban American landscape as well.

Players came from every social and economic strata of American society. A few were first generation immigrants while many more were second generation stock. Some were considered native born, which did not mean Native Americans, rather they were of Anglo-Saxon heritage of multiple generations. Our current perception that a high percentage of early professional players met the contemporary definition of immigrants is mirrored in this observation from an 1886 issue of The Sporting News: “The players on the diamond are of various nationalities. Nava of Baltimore is a Spaniard, McKeon, Reddy Mack, and Pete Browning are Italians, while only a few are Americans.”3 This statement seemingly ignores the large number of second generation Irish-Americans playing the game, yet tacitly acknowledges them, and embodies the nineteenth-century perception that even native-born second-generation players were still “foreigners” when it states there are “few Americans” playing the game. The number of first and second generation immigrant players may have been nearly thirty percent.4 Regardless of national or ethnic background, all players of the 1880s exercised the new social and economic status provided them by baseball to seek further opportunity — with varying degrees of intensity and imagination.

EARNING POTENTIAL & THE WEALTHY

The need for a player to seek employment depended on the circumstances of the individual. The average baseball salary in the 1880s was around $2,000. In 1880 the highest salaried player was Cap Anson at $1,900, but by 1889 Fred Dunlap and Buck Ewing were bringing in $5,000 each, while others were reportedly making as much as $4,000. Owners may have often paid their star players more than the contract indicated. Bench or change players sometimes signed for $1,200–$1,500. The average American’s income of the era ran between $800 and $900 a year, but census records — which excluded many better-paying positions — cite a figure of $376. Many of the players considered in this essay possessed either a skilled trade or education that would have allowed them to make up to $1,000 or more annually outside of baseball. Whether a player worked or not during the offseason, or after his career ended, depended on his earning ability as a player, marketable skill set in the work world, his education, and ambition.5

The need for a player to seek employment depended on the circumstances of the individual. The average baseball salary in the 1880s was around $2,000. In 1880 the highest salaried player was Cap Anson at $1,900, but by 1889 Fred Dunlap and Buck Ewing were bringing in $5,000 each, while others were reportedly making as much as $4,000. Owners may have often paid their star players more than the contract indicated. Bench or change players sometimes signed for $1,200–$1,500. The average American’s income of the era ran between $800 and $900 a year, but census records — which excluded many better-paying positions — cite a figure of $376. Many of the players considered in this essay possessed either a skilled trade or education that would have allowed them to make up to $1,000 or more annually outside of baseball. Whether a player worked or not during the offseason, or after his career ended, depended on his earning ability as a player, marketable skill set in the work world, his education, and ambition.5

A handful of players were financially well off, those with money of their own or who stood to inherit significant fortunes. Pitcher Lev Shreve, briefly with Baltimore and Indianapolis, was reported to come from a wealthy family. Shreve was worth $75,000 in his own right and was said to play ball for the fun of it. Two-time 40-game winner Bob Caruthers was set for life with $50,000 and stood to inherit over $300,000 more from his mother in a well connected East Tennessee family. German immigrant Willie Kuehne, who spent most of his ten-year infielding career in Pittsburgh, was born in Leipzig, in modern day Germany, and inherited nearly $75,000 one midseason from a relative in the old country. Emil Gross, five-year catcher with three teams, gave up the demanding position when he inherited $50,000.6

Others, while not so notably wealthy, did come from prosperous or comfortable families. Future Hall of Fame inductee and 328-game winner John Clarkson was the son of a prominent, successful jeweler and business associate of Harry Wright. The business district in Ilion, New York, was named “Hotaling Block” because it was owned by Pete Hotaling’s family. The real estate was waiting for him after he roamed the outfield for six teams in a nine-year career. Some others who might be considered well into the middle class include eight-year, seven-team pitcher-outfielder Ed “Cannonball” Crane whose father was a prosperous tailor, three-year Athletic outfielder Jud Birchall whose family did well in textile, and the popular second generation German immigrant and general utility man for the Baltimore Orioles, Joe Sommer, whose father was a successful hotelier. There are indications that nearly eleven percent of major league players had substantial financial support to fall back on if baseball did not work out for them.7

WORKING MEN AND BUSINESS VENTURES

Not everyone was born to the manor. Players were often apprenticed to the trades while still in their teens, before baseball propelled them into a new financial status. Jocko Milligan was apprenticed to a blacksmith at Girard College for Orphans before turning to real estate investment during his ten-year catching career. Baltimore native Frank Foreman, who pitched for four different major leagues 1884–1902, was one of many machinists. Bricklaying, plastering, plumbing, and carpentry were among the many trades players learned and practiced.

The young Tim Keefe, on his way to 342 wins and a belated Hall of Fame induction, soured on the trades early when he was stiffed on a bill for a house he built. Buffalo-born George Myers — primarily a catcher in the National League for six years — was reported to have built his $5,000 home with his own hands. Matt Kilroy once tried to use his glassblowing skills as a bargaining ploy in his contract negotiations with Billie Barnie of the Baltimore Orioles. He stated he was perfectly willing to go back to his old job where he could make $20 a week. With a $2,600 offer on the table, no one took him seriously. Things were so rough-and-tumble in the baseball world of 1885 that Baltimore catcher Bill Traffley declared all players should get paid at least $6,000 a year for risking their lives on the diamond. A local newspaper responded that if the game was too dangerous for his liking, he could always go back to his old job as brakeman on a gravel train. Bill stuck to catching. Those apprenticed or later working at a trade came to thirty percent of the players noted.8

While some would continue in the trades, others would try to parlay their baseball wages into various investments. Although rarely specified in the sources, it is certain that their notoriety propelled players into new social and business circles. Through those contacts, they could find better jobs, as well as enter into business ventures on their own, with teammates, or in partnerships with avid, well heeled fans who were happy to say they were a business associate with a local hero of the diamond. Nearly forty-three percent of the players considered in this essay ventured into assorted schemes, speculations, and opportunities.

After his bad experience in the construction business, Keefe put down his hammer, studied accounting and shorthand, opened a sporting goods store with fellow Metropolitan pitcher Buck Becannon, and invested in real estate in his hometown of Cambridge (MA) and Boston. It was reported he turned down a $30,000 offer for one piece of property, holding out for $50,000 because the city was looking to build a new library on the site.

While real estate was no more popular than other ventures, some did look to speculate in the expanding of the nation. Outfielder and yachtsman Ed Andrews became wealthy investing in land on Florida’s east coast during his eight-year career, and outfielder Abner Dalrymple actively tried to swap his ranch in Nebraska for one in California in 1888.9

Mickey Welch, whose Irish immigrant father was a ferrier by trade, tried his hand in a hotel, a saloon, cigar store, and a milk production venture with his sons. Then he hired on as steward of the Holyoke Elks Lodge, before working at the Polo Grounds later in life. After he blew his arm out, Matt Kilroy returned to his home town of Philadelphia where he gave up glass blowing and owned a popular restaurant and saloon near Shibe Park. It was the place for Philadelphia baseball fans to meet for many years before and after games.10

Mickey Welch, whose Irish immigrant father was a ferrier by trade, tried his hand in a hotel, a saloon, cigar store, and a milk production venture with his sons. Then he hired on as steward of the Holyoke Elks Lodge, before working at the Polo Grounds later in life. After he blew his arm out, Matt Kilroy returned to his home town of Philadelphia where he gave up glass blowing and owned a popular restaurant and saloon near Shibe Park. It was the place for Philadelphia baseball fans to meet for many years before and after games.10

By far the most popular business or investment for a ballplayer of the 1880s was the saloon, sometimes included as part of a hotel, restaurant, or billiard room. Some were advertised as sports bars and were touted as meeting places where players and fans alike could commiserate about the latest baseball news over a beverage. Baseball-related names for these establishments were common. Orioles catcher Bill Traffley couldn’t get his $6,000 and wasn’t going back to the gravel train, so he teamed up with pitcher and batterymate Hardie Henderson and opened up “The Battery” in Baltimore. Baltimore backup catcher Dick Mappes went to the St. Louis Maroons the following year, where he and pitcher Jumbo McGinnis opened an establishment under the same name. While some saloons, like Kilroy’s, were successful, other players probably should have stayed out of the business. When it was reported that knockabout second baseman Dasher Troy had opened a “gin mill” in New York, it was followed with the comment that Dasher need only find a dozen customers such as himself to have “no trouble making a go of it.” Former promising pitcher Fred Goldsmith was thought to have fallen far from his days as “Adonis of Chicago” when he turned up working a saloon in Detroit “…a plain fourteen-hours-a-day hired man.” Whether owners, managers, barkeeps, or salesmen, a little over sixteen percent player involvement was enough to prompt contemporary observations of a glut of players in this particular line of work, and that there were plenty of other opportunities available if they would only broaden their interest.11

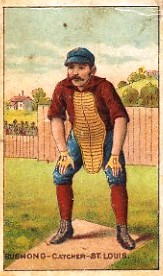

Some pursued an education before, during, or after their playing days to enter a profession. Some of the better known universities mentioned were Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Penn State, Cornell, Brown, Northwestern, Holy Cross, and the University of Pennsylvania. After five years in the outfield with three clubs, Jimmy Manning graduated from the Massachusetts School of Pharmacy and entered that profession. Veteran catchers Doc Bushong and George Townsend, perhaps understandably given the nature of their position, became dentists. Hall of Fame inductee John Montgomery Ward, said by some to be the most accomplished individual to ever play baseball, and the aptly named Orator O’Rourke, became well known attorneys. Within two years of a one-game stint for Detroit in 1884, Walt Walker was elected prosecutor of Isabella County in Michigan.

Mark Baldwin, a workhorse pitcher for five teams in three different major leagues over seven years, and Cleveland’s three-game tryout Doc Oberlander were among those who received medical degrees. Boston and Athletic backup catcher Thomas Gunning took off his equipment to became medical examiner for New York City, and later assisted on the parents of Lizzie Borden murder autopsies. Ohio native Lee Richmond’s best years as a pitcher came with the shortlived Worcester Brown Stockings. He later put aside his medical degree — earned from The College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City — to become a high school principal and teacher in Ohio where he taught Greek, math, physics, history, and chemistry, in addition to coaching and conducting the orchestra. In 1921 the multi-talented Richmond took on new responsibilities as professor and dean at the University of Toledo.

While playing for four major league teams in two years, Frank Olin was working on a degree from Cornell. He later ran a large commercial construction business in New Jersey specializing in power plants, mining facilities, and munitions factories. Over eight percent of the players looked at from this decade were found to have entered an educated profession.12

There was no shortage of artistic talent among baseball players of the era. Long John Reilly’s mother recognized her son’s abilities early and apprenticed him to prestigious Strowbridge Lithograph Co. where he specialized in circus posters and quickly earned a salary that rivaled his baseball earnings. Playing in Cincinnati, primarily for the Association club, he juggled the two lucrative careers. Reilly also painted artistically and was widely recognized for his talent. Mark Baldwin was another painter of note. He found the time between baseball, education, and a medical practice to specialize in landscapes.13

Norm Baker was a marginal pitcher for three American Association clubs in three years, but his first class baritone landed him lead roles in the offseason with the Ford Opera Co., for whom he appeared in Memphis. Baker may have been a bit of the diva, for he was said to be contrary and temperamental.

When he wasn’t playing football or running two to three miles a day to stay in shape, Emmett Seery patrolled the outfield for seven different clubs over nine years for all four major leagues between 1884 and 1890. In his spare time he sang in “The Chimey of Normandy” with the Peterson Opera in Indianapolis one winter. Sy Sutcliffe, who bounced through seven major league teams over eight years as a utility player, was another with a classical music bent and was “blowing the keys off a clarinet” for the Savannah Symphony Orchestra in 1886.14

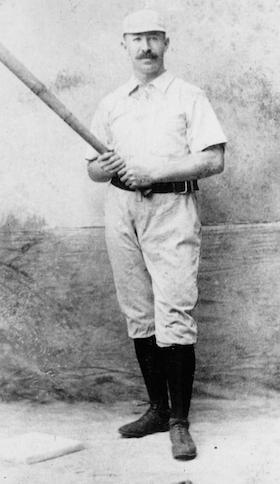

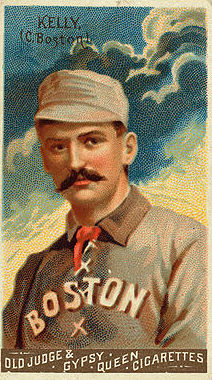

While actual acting ability could be lacking, their star status allowed many players to take to the stage. Cap Anson’s and King Kelly’s exploits in front of the vaudeville footlights are well documented. Arlie Latham, star third baseman for the St. Louis Browns of the 1880s and often referred to as “The Freshest Man on Earth,” headlined in Lew Simmons’s minstrel shows but later tried his hand at acting as well. Due to make $90 a week in the Simmons backed farce-comedy, “Fashions,” Arlie ended up suing for lost wages of $394.12. It doesn’t appear he ever acknowledged that his acting may have contributed to the show’s demise. Harry Stovey, whose best years came with the Athletics, was scheduled to tour with a Simmons show in 1886. In addition to being one of the better players of the decade, Stovey was a first rate clog dancer. It may have been facetiously reported that Harry was to dance to the tune of “Footsteps in the Sand.”15

While actual acting ability could be lacking, their star status allowed many players to take to the stage. Cap Anson’s and King Kelly’s exploits in front of the vaudeville footlights are well documented. Arlie Latham, star third baseman for the St. Louis Browns of the 1880s and often referred to as “The Freshest Man on Earth,” headlined in Lew Simmons’s minstrel shows but later tried his hand at acting as well. Due to make $90 a week in the Simmons backed farce-comedy, “Fashions,” Arlie ended up suing for lost wages of $394.12. It doesn’t appear he ever acknowledged that his acting may have contributed to the show’s demise. Harry Stovey, whose best years came with the Athletics, was scheduled to tour with a Simmons show in 1886. In addition to being one of the better players of the decade, Stovey was a first rate clog dancer. It may have been facetiously reported that Harry was to dance to the tune of “Footsteps in the Sand.”15

For those not musically or artistically inclined, the era offered other opportunities. In the midst of a six-team, three-league, seven-year utility career, Dave Rowe spent the 1884 offseason mining in Colorado with no success. He then returned to play in 1885 and manage the Kansas City Cowboys the following year. Joe Moffet was a borderline major league player, while brother Sam showed more promise. Both debuted in the major leagues in 1884 only to toss aside their baseball careers for a chance to work the silver strike in Butte, Montana. They struck it rich. The West Virginia brothers pulled out the princely sum of $231,000 worth of silver and gold. Bitten by both the baseball and the mining bugs, Sam came back east three years later to play in the major leagues for two more years before returning to the mining business in Montana and Canada for good.16 Although not a player, Pittsburg Allegheny owner and American Association president Dennis McKnight was another baseball figure with a mining payoff when his silver holdings in Mexico began to produce towards the end of the decade. McKnight was variously reported in Arizona or New Mexico, looking the cowboy, rubbing elbows with the brokers of El Paso, trying to raise the capital to expand his venture.17

While mining is a gamble, the hard work involved in it was not for everybody. Maryland native Dave Foutz spent some of his early years with his brother in the rough and ready minefields of Leadville, Colorado, where he learned games of chance. As a St. Louis Brown, Foutz once ran a floating poker game in San Francisco while playing winter ball there. The handsome Foutz fancied himself as much a professional gambler as a ball player. There is some question whether gambling allowed Foutz to play baseball, or if baseball allowed him to gamble. At least one contemporary newspaper felt that it was his baseball earnings that bankrolled his penchant for gambling, it being reported he once lost a season’s salary at the “green table” in New Orleans.

Six-year catcher and utilityman Dell Darling and two-year outfielder Jon Morrison were another pair looking for easy money-as train robbers. Not to be confused with the likes of the James or Younger brothers, this gang would board trains, furtively rummage through the luggage, and pass the loot off to accomplices at stops along the way. A hundred people were implicated in the scheme working out of Darling’s hometown of Erie, Pennsylvania.18

During a seven-year career as a catcher, primarily with the Cincinnati “Porkopolitans” of the American Association, Kid Baldwin once tried his hand at sheepherding. It appears the Kid had a hard time keeping track of himself, much less a herd. It was later reported that he was engaged to a wealthy heiress, and a newspaper wag opined that Baldwin would “go through her wealth like a bullet through cheese.” Many players found jobs in the offseason as referees in the New England Polo League, for which the irrepressible Arlie Latham was turned down. Latham later found his dream job as Commissioner of Baseball of England, a post he held for seventeen years.

The fantasy camp concept is not exclusive to our era: When Mark Baldwin wasn’t going to medical school, playing baseball, or painting, he found the time to teach fans the art of pitching at a pricey $25 each. All told, “miscellaneous” jobs accounted for about sixty-four percent of ballplayers’ employment activities.19

SPORTS AND THE SPORTING LIFE

Many players hewed close to baseball and sports in general. Ten-year veteran Tom York, Hall of Fame pitcher Tim Keefe, and stalwart Louisville hurler Guy Hecker were among those who opened sporting goods businesses. Others simply invested, managed, or worked for them in some capacity. Apparently, the temperamental Norm Baker passed on one opera season and spent the winter hand stitching baseballs for Al Reach. It was said he could turn out three dozen balls a day.20

Harry Decker and Ted Kennedy were two players who turned their efforts and imaginations to the game they played. Decker was one of those players from comfortable circumstances in Chicago who would later exhibit an enigmatic, if not bizarre, tendency to criminal behavior. A catcher by trade with six teams in three major leagues in four years, he patented his designs of a pioneering catcher’s mitt, and later worked and sold models through Al Reach who manufactured them. The patent was later sold to Spalding who marketed what would be known as the “decker.” The imaginative Decker also made improvements to the turnstile.

Kennedy, who lasted only two seasons in a major league pitching box, also patented his novel glove designs, which were subsequently sold to Al Spalding. Kennedy and Decker were responsible for at least some of the innovations that transitioned baseball from form-fitting to flexible padded gloves. Kennedy also opened a baseball school specializing in the art of throwing the curve ball. If you couldn’t physically make it to the class, he wrote a book, complete with diagrams, which an aspirant could purchase in order to learn the pitch at home. Kennedy then came up with an early pitching machine that was used by Jimmy McAleer and the St. Louis Browns prior to the 1904 season to improve their hitting. The pitching machine may have worked fine, but it did not have the noticeable effect on the Browns’ batting averages McAleer had hoped for. The Browns went from seventh to sixth in league hitting while improving from .011 to.005 below the league average, but the team average actually dropped from .244 to .239. And while we may want to believe the story that the creative Kennedy died of electrocution while trying to invent the electric score board, his obituary states that the coroner attributed his early demise to fatty degeneration of the heart.21

The 1880s may have been a decade of dissipation and rowdy behavior for many players, but a significant number realized that they made a significant salary playing baseball, hence they could make more money — for a longer period of time — if they took care of themselves. While some may have espoused billiards, hunting, and fishing with tongue in cheek, others had a firmer grasp on what it took to stay in shape. Many went to the gym to work out or took up activities such as handball, football, polo, running, and skating, calculated to keep them in condition throughout the year.

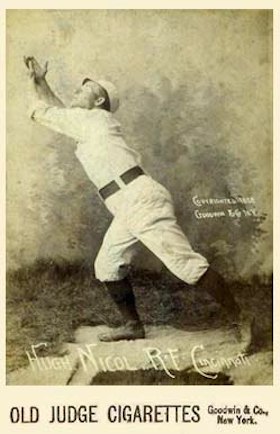

By 1886 Silver Flint had used his baseball earnings to buy his own gym in Chicago. Flint’s twelve years behind the plate, mostly with the Chicago Nationals, may attest to the success of his offseason conditioning. Little Hugh Nicol, a native of Scotland and described as the smallest man in baseball, is probably the pinnacle of those who chose to work out in the offseason. Always known as a fitness advocate the 145-pound Nicol was often referred to as an acrobat. After a bout with malaria, Hugh encountered a Professor Muegge who taught him a new regimen. In the offseason Nicol was hired by gyms as a manager or trainer, and other players followed his example by working out. Nicol, like Emmett Seery, was an early advocate of long distance running as a way to stay in shape, often completing the eighteen mile distance from Rockford, Illinois to Beloit on the Wisconsin border during the offseason. The diminutive yet strong and agile Nicol once took on the 315-pound wrestler Frank Sully, beating the giant in a two out of three falls in the first two rounds.22

By 1886 Silver Flint had used his baseball earnings to buy his own gym in Chicago. Flint’s twelve years behind the plate, mostly with the Chicago Nationals, may attest to the success of his offseason conditioning. Little Hugh Nicol, a native of Scotland and described as the smallest man in baseball, is probably the pinnacle of those who chose to work out in the offseason. Always known as a fitness advocate the 145-pound Nicol was often referred to as an acrobat. After a bout with malaria, Hugh encountered a Professor Muegge who taught him a new regimen. In the offseason Nicol was hired by gyms as a manager or trainer, and other players followed his example by working out. Nicol, like Emmett Seery, was an early advocate of long distance running as a way to stay in shape, often completing the eighteen mile distance from Rockford, Illinois to Beloit on the Wisconsin border during the offseason. The diminutive yet strong and agile Nicol once took on the 315-pound wrestler Frank Sully, beating the giant in a two out of three falls in the first two rounds.22

Most players were not as ardent as Nicol, but both The Sporting News and Sporting Life refer to many who were in the gym by January, with some starting immediately after the season ended or at least by Christmas. Nearly twenty percent of the players considered from the 1880s were found to have made a concerted effort to stay in condition during the offseason. This does not include the legion who would scramble in to the gym or run down to Hot Springs, Arkansas, just before the start of spring training.23

In 1886 there were three major league clubs that required their reserved players to participate in offseason training. The Sporting News advocated this program, “…that men having thousands of dollars invested in a business on which so much depends upon the physical conditioning of their men should pay so little attention to the matter of training these people…Take these same men and let them put the money they invested in base-ball into horse-flesh. Would they dare send their horses out on the trotting or running circuit in the spring without training them?” The writer continued, recommending… “vaulting, string jumping, horse, parallel, and horizontal bars, etc…three clubs in the country have their men working a systematic course of training,-the St. Louis League, the St. Louis American and the Cincinnati Club.”24

WINTER BALL

Not every ballplayer of the 1880s worked or worked out in the offseason, nor did they idle away their time. When the baseball season ended, the south was still warm and without major league franchises. It was considered a prime market to take advantage of by baseball owners. In any given year four or more Association or League teams might embark on postseason tours. New York, Boston, Chicago, and the St. Louis clubs were among those extending their seasons into these untapped markets. These teams were sometimes supplemented with players from other clubs looking to earn extra money. They would tour the south before heading to California, which was referred to as playing on “the slope.”

Players were free to sign individual contracts in the offseason with teams in the south or west where weather allowed for extended seasons. California, naturally, was the most popular destination for those looking to play year round, but others played with teams throughout the south from El Paso to New Orleans, from Savannah to Havana, Cuba.25 Winter play gave them a chance to stay in shape, stay sharp, or even improve their skills.

In addition to the trades and professions, baseball players gravitated to jobs as policemen, firemen, farmers, retailers, pool hustlers, bakers, and cigar rollers. Railroads were a major employer of the day, so many found work there. While subject to opportunities of their times and their individual limitations, ballplayers’ pursuit of financial success is in some ways unique to their particular point in American history. Many squandered the opportunities that baseball fame and fortune provided in bars, bawdy houses, and gambling dens. But at an early point in organized professional baseball, others recognized the rare chance baseball provided them. They attempted to maximize their careers and earnings by training to stay in shape, and using their income for education or to otherwise invest in their prospects for the future.

MARTY PAYNE is a member of the Baltimore Babe Ruth Chapter of SABR and lives in St. Michaels, Maryland. The current article was based on a presentation made at the SABR Frederick Ivor-Campbell Conference on 19th Century Baseball in 2016.

Sources

Baltimore Day/Daily News 1882-1891

Baltimore News American 1882-1891

SABR American Association History Project files

SABR Biography Project

The Sporting News 1885-1889

Sporting Life 1886-1889

Morris, Peter; The Catcher, Ivan Dee, Chicago, 2009

Dewey, Donald, Acocella, Nicholas; The Ball Clubs, HarperPerennial, 1993.

Haupert, Michael, Major League Baseball’s Salary Leaders, 1874-2012, Business of Baseball Committee Newsletter, Fall 2012.

Clarence D. Long, Wages and Earnings in the United States, 1860-1890, Princeton University Press, 1960.

Members of the American Economic Association, The Federal Census Critical Essays, MacMillan and Co., New York, March 1899.

Various writers, Railways of America, John Murray, London, 1890.

baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 Chief Joseph with the Nez Perce and the Sioux at Wounded Knee seem less a viable threat to Anglo-American migration than a fait accompli resistance.

2 For the increase of the railroads see Railways of America, for 1880 and 1889, including maps on pages 432 and 433. The estimated bison populations are from Wikepedia.com, specifically citing The American Buffalo, Conservation Note 12 for the bison population of 1870. For the nearly extinct population of 1889, Hornday, William T., “The American Natural History,” New York, C. Scribner and Sons, 1904.

3 “Funny Cracks,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1886, 5.

4 This percentage was estimated from the 81 SABR Biography Project pieces considered for this essay. Of those 24 were determined to be first or second generation immigrants.

5 For the top salaries of the decade see Major League Baseball’s Salary Leaders, 1874-2012, Michael Haupert, Business of Baseball Research Committee Newsletter, Fall 2012. Haupert cites $864 as an average annual income for the mid-1870s. For the census figures see The Federal Census Critical Essays, American Economic Association, MacMillan and Co., New York, 1899, 356. The chart indicating the earning abilities of skilled trades of 1880 is in Clarence Long, Wages and Earnings in the United States, 1860-1890, Princeton University Press, 1960, 94.

6 For Lev Shreve see Baltimore Daily News, September 21, 1887. All notes from the Baltimore papers were done by the author in the early 1990s and did not include headings or page numbers. Those sources have not been revisited since. Further citations from the two Baltimore sources in this essay will not have heading or page. The background of Bob Caruthers is in the SABR Biography Project, “Bob Caruthers,” by Charles F. Faber. For Caruther‘s connection to the wealthy and influential east Tennessee McNeal family see also, “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1886, 5. Kuehne’s inheritence is cited in “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, August 11, 1886, 5 Emil Goss is found in “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1886, 5. Biography Project pieces cited in this essay are referenced for sources and footnoted to varying degrees of detail. For this and all further citations from the project the reader is referred to those documented pieces for primary sources. Ensuing citations from the project will be abbreviated as SBP.

7 See SBP for “Jud Birchall,” by Paul Hoffman. SBP, “John Clarkson,” by Brian McKenna. SBP, “Ed Crane,” by Brian McKenna. SBP, “Pete Hotaling,” by John F. Greene. 29 of the 269 players seem to have come from families of wealth or the comfortable middle class. Admittedly, this is an impressionistic projection since no specific definition of economic status was used, and sources merely needed to mention noteworthy property or a successful family business.

8 On Jocko Milligan see, SBP, “Jocko Milligan,” by Ralph Berger. Frank Foreman, “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, November 27, 1889, 7. SBP, “Tim Keefe,” by Charlie Bevis. The note on George Myers is from The Sporting News. November 25, 1886, 6. The Matt Kilroy holdout is found in the Baltimore News American, April 4, 1888 and April 10, 1888. For Traffley’s opinion and the response see Baltimore Daily News, August 31, 1885. Traffley’s demand was triple the typical major-league salary of the time, six times that of a skilled tradesman, and sixteen times that of a typical American laborer. 82 of the 269 players considered for the essay worked in the trades at some point in their lives. The trades included but not exclusive to the construction industry, blacksmithing, machinists, and other assorted skilled professions like butchers, bakers and confectioners, among others.

9 See SBP, “Tim Keefe,” by Charlie Bevis. Also on the real estate see “Notes and Comments, Sporting Life, January 23, 1889, 2. On Ed Andrews see SBP “Ed Andrews,“ David Nemec; also Sporting News, October 25, 1886 5. Abner Dalrymple can be found in “Caught on the Fly, “Sporting News, January 14, 1888, 4; “Caught on the Fly,“ Sporting News, February 11, 1888, 5 and “Caught on the Fly,” Sporting News, February 25, 1888, 5.

10 For Mickey Welch see SBP, “Mickey Welch,” by Bill Lamb. For Kilroy’s post career see SBP, “Matt Kilroy,” by Charles F. Faber. 115 of the 269 players took the plunge into the world of business investment and speculation hoping for a big pay off.

11 The Traffley-Henderson venture is noted in the Baltimore News American, January 3, 1886. The Mappes-McGinnis in “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1886, 5. The opinion of Dasher Troy’s prospects are found in “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1889, 3. And Fred Goldsmith’s apparent fall from grace is found in “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1887, 5. 44 players of 269 were noted as being in the liquor business.

12 On Jimmy Manning see “The Kid and Jimmy,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1889, 3. For Bushong see SBP, “Doc Bushong,” by Brian McKenna. George Townsend is mentioned in the Baltimore Daily News, October 9, 1890. See SBP, “John Montgomery Ward,” by Bill Lamb. Walt Walker is in “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, December 1, 1886, 3. Doc Oberlander is in “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, July 27, 1887, 5. See the SBP, “Mark Baldwin,” by Brian McKenna. Thomas Gunning is in “Louisville Briefs,” Sporting Life, December 14, 1887, 1, also SBP, “Thomas Gunning,” by Bill Lamb. See SBP, “Lee Richmond,” by John Houseman. SBP, “Orator O’Rourke,” by Bill Lamb; SBP. “Frank Olin,” by Guy Waterman. Research identified 22 of the 269 entering an educated profession.

13 See SBP, “John Reilly,” by David Ball., and “Mark Baldwin,” by Brian McKenna.

14 See SBP, “Norm Baker,” by David Nemec. The citation for Emmett Seery playing football is in “Loafing Season,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1886, 3. His running is found in “Caught on the Fly,“ The Sporting News, March 17, 1886, 2. The opera gig is from “Indianapolis Mention Notes,” Sporting Life, November 21, 1888, 6. Sy Sutcliffe is found in, “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1886, 5.

15 Arlie Latham’s stage woes are from “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, April 24, 1889, 2. Stovey’s planned tour is from “Funny Cracks,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1886, 5.

16 Dave Rowe’s Colorado expedition is in the Baltimore Day (Daily News) September, 25, 1883. See SBP “Joe Moffet,” by Carole Olshafsky, and SBP, “Sam Moffet,” by Carole Olshafsky for their mining success. Sam’s return is from “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, June 1, 1887, 10.

17 For reports of Dennis McKnight’s mining exploits see, “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1887, 3. Also “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 23, 1887, 5. See “From Pittsburg,” Sporting Life, October 26, 1887, 1. And “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, November 30, 1887, 5.

18 See SBP “Dave Foutz,” by Bill Lamb. For the gambling losses in New Orleans see “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1886, 3. The train robbery scheme is covered in SBP “Dell Darling,” by Brian McKenna.

19 See SBP, “Kid Baldwin,” by David Ball. The prediction of the heiress’s fortune is in “Funny Cracks,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1886, 5. See SBP on, “Arlie Latham,” by Ralph Berger. Mark Baldwin’s scheme for rich fans is from “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 9, 1887, 3.

20 Citations in newspapers for players involved in the sporting goods business are many. The citations used here are from SBP, “Tim Keefe,” by Charlie Bevis also; SBP, “Guy Hecker,” by Bob Bailey. See SBP, “Norm Baker,” by Dave Nemec for Baker’s prowress stitching baseballs. There were 173 notations of players working at miscellaneous positions. They included a multitude of railroad positions, firemen, policemen, clerks, and unidentified government positions, all requiring varying degrees of skills and abilities but not easily classifiable.

21 For Decker’s connection with Reach see “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, November 20, 1889, 3. Peter Morris devotes a chapter to the strange life of Harry Decker in, The Catcher, pp. 189-207. For Kennedy’s efforts see SBP, “Ted Kennedy,” by Craig Lammers. The Hall of Fame has possession of many of Kennedy’s glove designs, not all of which are practical, and a copy of his instructional book on the art of the curve. The league and Browns batting average comparisons are from baseball-reference.com.

22 For Silver Flint see “The White Stockings, The Sporting News, March 17, 1886, 1. On Hugh Nicol, SBP, “Hugh Nicol,” by Charles F. Faber. For Nicol’s guidance from Professor Muegge see “Hugh Nicol’s New Job,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1886, 1. The bout with Frank Sully is found in “Little Nick As A Wrestler,” The Sporting News, December 11, 1886, 5.

23 The criteria the author used for serious training were those players who were working out by January. This allows for a break through the holidays. 52 players of the 269 were found to return to some sort of working out by the first month of a new year.

24 See “Training Players,“ The Sporting News, March 17, 1886, 2.

25 For the growing popularity of winter ball in the 1880s see “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1886, 5. While these winter season players were not tracked for the purposes of this essay, they warrant a more thorough treatment as a means of both training and employment. If nothing else, professional baseball players were probably better traveled than most other segments of the American population of the decade.