It’s a Major League City or It Isn’t: San Diego’s Padres Step Up to the Big Leagues

This article was written by John Bauer

This article was published in Time For Expansion Baseball (2018)

National League president Warren Giles was in San Diego for Opening Day, April 8, 1969, and here joins Buzzie Bavasi holding an aerial photograph of the Padres’ new ballpark, San Diego Stadium. (Courtesy of Tom Larwin)

San Diego’s quest for major-league baseball began in the mid- to late 1950s, around the time Los Angeles and San Francisco ascended to “the bigs.” Home of the Pacific Coast League Padres since 1936 and backed by banker and businessman C. Arnholt Smith, San Diego looked for an opportunity to obtain major-league baseball.

The local Chamber of Commerce and the Greater San Diego Sports Association had been sending a representative to baseball’s winter meetings to lobby quietly on behalf of the city.1 Smith had been part of the Hank Greenberg–Ralph Kiner group that sought the American League expansion team for Los Angeles that was ultimately awarded to Gene Autry for the 1961 season.2 A man with a penchant for beige suits, Smith was characterized as something of a mystery man despite heading a diverse portfolio of business interests.3 He headed the U.S. National Bank as well as the Westgate-California Tuna Packing Corporation, which was a business conglomerate with seafood, ground transport, aviation, hotel, and insurance interests.

To complement his bid, Smith teamed up with Los Angeles general manager Buzzie Bavasi. An executive with the Dodgers for almost two decades, Bavasi saw his chance to achieve an ownership role by partnering with Smith. Together, the Smith-Bavasi team provided a formidable combination of financial strength and baseball experience. San Diego itself seemed ripe for big-league ball. Noting the area population of one million (and growing), Bavasi saw the potential for success: “If everybody in the city of San Diego attends one game, we’ll do all right.”4

In addition, community support for major-league sports was evidenced in November 1965, when 72 percent of those voting approved city bonds that would finance construction of the 50,000-seat San Diego Stadium. While the stadium would also house the American Football League’s Chargers, baseball officialdom took notice that the multipurpose facility could also accommodate a baseball team.

The National League expands

The National League had not been seeking to expand in the late 1960s, but the senior circuit’s hand had been forced by the American League. Attempting to assuage Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington over Kansas City’s loss of the Athletics to Oakland (and to head off potential antitrust issues that an angry US senator might cause), the American League elected to expand. On October 18, 1967, the junior circuit agreed to admit Kansas City and Seattle for the 1969 season.

Although the move caught the National League by surprise, it agreed in principle in November to expand similarly without establishing a date for doing so. Mets chairman Donald Grant stated, “The question no longer is whether the National League expands – but when.”5 The NL formally agreed to do so on December 1, 1967, during the winter meetings in Mexico City.

In voting to expand, the National League left open the possibility that its expansion might not occur in concert with the American League; that is, the National League seemed poised to wait as late as the 1971 season before increasing its membership. The uncertainty did not dissuade cities from preparing their pitches as San Diego, Dallas-Fort Worth, Buffalo, Milwaukee, and Montreal emerged as the serious contenders.

To evaluate the applicants, the National League appointed an expansion committee of Walter O’Malley (Los Angeles), John Galbreath (Pittsburgh), and Roy Hofheinz (Houston). The composition of the committee was important in two respects. Not only did Bavasi have a close ally on the committee in O’Malley, but it was assumed Hofheinz would block Dallas-Fort Worth in order to keep the Texas market to himself and the Astros. During a league meeting on April 19, 1968, the National League agreed not only that it would expand for the 1969 season but that a unanimous vote of an applicant city would be required for entry, with each city to be considered individually.

The National League convened in Chicago on May 27 with increasing expectations that the two expansion cities would be chosen. Eddie Leishman, general manager of the Padres of the Pacific Coast League, observed, “This just isn’t going to be another meeting where they postpone a decision until the next meeting.”6

After 10 hours of deliberations, a likely consequence of the unanimity requirement, NL President Warren Giles announced that San Diego and Montreal were accepted into the league. Although it was assumed Bavasi’s status as a baseball insider would assist the city’s bid, it was revealed later how close the Padres came to missing out. To some surprise, the National League accepted Montreal unanimously early in the voting. Buffalo clinched nine votes with San Francisco’s Horace Stoneham holding out for San Diego.7 At one point, San Diego had the support of only four owners as some Eastern owners lobbied colleagues for two Eastern cities.

After 18 ballots, momentum shifted away from Buffalo with San Diego’s bid the beneficiary. When the contenders were called into the meeting room, O’Malley tipped off Bavasi as to the result with a smile followed by the question, “You got your ulcer yet?”8 Indeed, Bavasi acknowledged a debt to O’Malley and Stoneham, “We owe a lot to Walter and Horace, they were for us all the way.”9

Smith had not accompanied Bavasi to Chicago but sent his attorney, Douglas Giddings. After speaking with Smith, Giddings reported, “He was happy but he wondered why the meeting lasted so long.”10 Smith confirmed his appreciation later: “I am gratified that years of planning and dreaming have come to reality today. … The action in Chicago by the National League owners is another expression of confidence in the great future that lies ahead for San Diego.”11

The business side of becoming a big-league team

In the aftermath of the National League meeting, attention shifted to assembling San Diego’s major-league organization. At the executive level, Smith was named chairman of the board, Bavasi would serve as president, and Leishman was elevated from the general-manager position of the Pacific Coast League Padres to the same spot with San Diego’s new National League club. Additionally, the National League set the expansion fee at $10 million, the first $1 million of which was due on August 15.

Of the $10 million aggregate, $6 million would be allocated to compensate the other National League clubs for each of the 30 players to be taken during the expansion draft to the tune of $200,000 each with the other $4 million constituting the actual expansion fee. Moreover, an additional $2.5 million would have to be placed in escrow as working capital. Bavasi delivered the first million on time, flying to New York on August 15 with 10 checks, each for $100,000 and all signed by Smith. The Padres officially joined the National League with a $6 million payment on January 28, 1969, with the remaining $3 million to be paid over the next three years.

With the franchise in hand, the Padres turned to the business issues of negotiating contracts for local radio and television rights and a lease for San Diego Stadium. The Padres hoped to maximize local radio and television in light of the condition that neither expansion club would receive a share of national television revenue until the 1972 season.

However, the fact that San Diego was hemmed in by the two-club Los Angeles market to the north and the Mexican border to the south caused some concern that the Padres would be hampered in their local negotiations. The team and local station KOGO announced an agreement at the end of July for both radio and television rights. Under the agreement, KOGO would broadcast all regular-season and some preseason games over the radio and telecast selected road games on its KOGO-TV station. Home telecasts were not anticipated.

While the two sides did not announce financial terms, they represented that the deal would compare “favorably” with those of the majority of major-league clubs.12 In September, the Padres broadcast team was in place: Jerry Gross and Frank Sims, formerly with the Cardinals and Phillies, respectively, would handle play-by-play, with Duke Snider doubling as color commentator and Padres scout.

Although the Pacific Coast League iteration of the Padres was already playing at San Diego Stadium, a new lease was required for the expansion team. San Diego City Manager Walter Hahn led negotiations on behalf of the city, with Giddings handling the matter on behalf of the ballclub.

The two sides reached a tentative agreement on June 13 with agreement on a 20-year term and a rental payment of 7.5 percent of gross ticket sales. The parties became stuck on the issue of an approximate $2 million subsidy from the city to the club and the terms of its repayment. The subsidy was intended to defray some of the costs to obtain the franchise. Accordingly, the city would pay the Padres $285,000 per year for seven years, but the two sides reached an impasse over how it would repaid.

After weeks of additional negotiations, Hahn delivered two tentative agreements to the city council on August 1. The parties to the first agreement were the city and the Padres, under which the club would pay a rental fee of 8 percent of ticket sales revenue over the 20-year term. The Padres would keep concessions revenue, but the city would receive the parking fees. The agreement also accounted for the Chargers, with Hahn stating that the football team would have “fair and equitable scheduling priority” when baseball and football season overlapped.13

The second agreement was between the city and San Diego Stadium Management Co., the latter entity formed by the Padres to manage, operate, and promote the stadium. The city would pay the management company the actual costs to maintain and operate the stadium on an agreed annual budget plus a 10 percent management fee.

Additional financial terms were intended to address the subsidy and repayment issue. The city would pay $306,420 annually for the first seven years of the agreement from local hotel-room taxes, payments that were to be reimbursed to the city over the final 13 years of the agreement based on a formula connected to Padres attendance.

The Board of Governors of the San Diego Stadium Authority approved the agreements on August 5, but the Chargers objected to the agreements during the city council meeting on the same day. Chargers attorney J. Stacey Sullivan argued that the agreements favored the Padres in a way that violated the Chargers’ lease with the city. In particular, Sullivan asserted that the Chargers had scheduling priority over the Padres and also wanted equal treatment in light of the city’s subsidy to the Padres. City attorney Ed Butler objected to Sullivan’s characterization and suggested that if the Padres and Chargers could not work through any potential scheduling issues, then “I suppose a jury of 12 housewives will make a determination that the businessmen can’t make.”14

When the Padres raised last-minute concerns that the lease would not guarantee them at least four weekend playing dates during August and September, Mayor Frank Curran snapped, “If the children can’t play nicely together, perhaps a divorce is in order. … I’m getting very tired and very disturbed by these two organizations.”

After an additional week of negotiations, the city council approved revised agreements that acknowledged the Chargers’ scheduling priority and required the Padres to consult with the Chargers before scheduling. If the Padres were forced to reschedule any games, the city would reimburse the team for any losses sustained up to a maximum of eight games.

Butler did not foresee a problem if the two teams worked together in good faith, and Bavasi offered that “[w]e’re delighted with the way things worked out. The city is satisfied, we’re satisfied and the Chargers should be satisfied.”15 As it turned out, there would be two conflicts during the 1969 season and the Chargers were definitely not satisfied. After withholding rent payments and demanding a revised rent-free lease agreement, the Chargers litigated their dispute with the city into the spring.

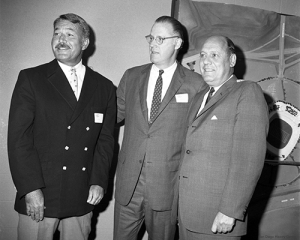

On the eve of the 1969 Opening Day are (left to right) Dr. Albert Anderson, a member of the San Diego Stadium Board of Directors; Bowie Kuhn Commissioner of Major League Baseball; and Padres’ president E. J. “Buzzie” Bavasi. (Courtesy of Tom Larwin)

Assembling the on-field product

Early speculation on the managerial appointment focused on Dodgers third-base coach Preston Gomez and then-Pacific Coast League Padres’ manager Bob Skinner. The Padres were then the Triple-A affiliate of the Phillies, and the parent club tapped Skinner in mid-June 1968 to replace Gene Mauch in the Philadelphia dugout.

While Mauch was believed to have interest in managing the National League Padres, Bavasi hired Gomez on August 29 on a one-year contract. The Cuban-born Gomez would be the first Latino hired to manage in the major leagues. Prior to his coaching stint in Los Angeles, Gomez managed successfully in Mexico, Havana, Spokane, and Richmond.

O’Malley delivered the news to Gomez, telling him, “Buzzie has asked us to release you, and of course we will cooperate. We hate to lose you, but you go with our blessing.”16 At the introductory press conference, Leishman commented, “There were other people we considered, but Preston is the man we wanted most.”17 Leishman also viewed Gomez’s reputation as a teacher to be an important asset in assembling a new, young team to compete in the National League.18

For his part, Gomez characterized himself as being a gambler in his management style. Gomez cautioned, “But you cannot gamble without speed and speed is something we’ll need in this big ballpark.”19 Gomez assembled his staff over the next month. His first coaching hires were made on September 12, with Wally Moon hired to be the batting and first-base coach and Pacific Coast League Padres coach Whitey Wietelmann to oversee the bullpen. Roger Craig, who managed Los Angeles’ Albuquerque affiliate in 1968, received the pitching-coach job the following week, and successful minor-league manager George “Sparky” Anderson rounded out the staff as third-base coach. Bavasi said, “Now we can get down to work and on with the building of a ballclub.”20

The expansion draft provided the main opportunity to harvest a roster capable to compete at the major-league level. Bavasi lured 20-year scouting veteran Bob Fontaine away from Pittsburgh to run San Diego’s scouting operation. Bavasi nonetheless had his own idea of the team he hoped to assemble: “The thing we have in mind is to concentrate on good fielders, ballplayers who can run and control a bat. Naturally, we’ll be after strength down the middle. … The ground is hard at [San Diego Stadium] and we must have a good center fielder.”21

Prior to the expansion draft, San Diego participated in baseball’s free-agent draft on June 6 in New York. Leishman selected 16 players, with pitcher-outfielder Luciano “Lou” Hernandez the prize of the bunch. Hernandez attended high school in Solana Beach, 30 miles north of San Diego, and Leishman was pleased to draft him.22 The Padres general manager said of Hernandez, “We didn’t think he would be around by the time we got our pick. He’s a real strong kid and we’re high on him.”23

The National League expansion-draft rules mirrored those for the American League. Each existing club would submit a list of 15 protected players by October 1, with the World Series representative permitted a delay. San Diego and Montreal would both select 30 players, meaning that the 10 National League clubs would lose six players each. After each of six rounds, the existing teams could add three more players to their protected lists, which were kept confidential. In fact, only San Diego and Montreal would be able to see the lists, the secrecy intended to protect trade values.

With the Royals and Pilots having a seven-month head start in preparing for the American League expansion draft, the Padres and Expos scrambled to obtain player information. The Giants and Cardinals made available personnel data as a courtesy to the new clubs, and Fontaine set about reviewing that information.24

The draft occurred on October 14, 1968, in the Versailles Room of Montreal’s Windsor Hotel, the same location as the National Hockey League’s “Second Six” expansion draft ahead of the 1967-68 season. San Diego won a coin flip with Montreal for the right to pick first, and the Padres used that choice to select “Downtown” Ollie Brown from the Giants.

Brown, a 24-year-old outfielder with a strong throwing arm, slumped in 1968 after hitting .267 with 13 home runs in 1967. His 1968 misery was compounded by a six-week suspension after clashing with Giants manager Herman Franks and refusing to report for a minor-league assignment in Phoenix.

With its second pick, San Diego chose pitcher Dave Giusti from St. Louis. Giusti had been traded from Houston after an 11-14 season to the National League champions the week before the draft, and made no attempt to hide his feelings. He complained, “I’m very disappointed. Nobody in St. Louis told me this was going to happen. I wanted to work for a championship club.”25

The Padres rounded out their first batch of selections with Dick Selma, 9-10, 2.75 ERA with the Mets, Al Santorini, a 20-year-old right-hander from the Braves organization, and Jose Arcia a “good glove, weak bat” second baseman from the Cubs.

The Padres brass drafted decidedly for youth with their next round of selections: Clay Kirby, a 20-year-old right-hander from the Cardinals organization; Fred Kendall, 19-year-old catcher from the Reds system; Julio Morales, an outfielder and another 19-year-old; and Nate Colbert, a 22-year-old first baseman-outfielder who hit .264 in 1968 for the Astros’ Triple-A club in Oklahoma City.

Craig became especially high on Kirby as he worked with his new pitcher, stating, “Kirby is a bulldog – he has determination as well as good stuff.”26 Of the second-round choices, only former American League Most Valuable Player Zoilo Versalles held veteran status and observers expected him to be flipped to another club.

In the third round, the Padres took Jerry DaVanon with the 12th pick. DaVanon, a 23-year-old shortstop from the Cardinals organization, was a native San Diegan. Unlike Giusti, he was excited to join the Padres. “Being picked by San Diego was the nicest surprise I’ve ever had,” he said.27 Braves reliever Dick Kelley was chosen 14th, and Dodgers outfielder Al Ferrara, who missed almost all of the 1968 season with a broken ankle, was taken with the 15th pick.

With their final 15 picks, the Padres continued to target youth but also grabbed established players who might have something to prove or provide trade value. From the Phillies, the Padres took outfielder Tony Gonzalez, a 32-year-old left-handed hitter, and infielder Roberto Pena, a 28-year-old who spent 1968 with the Pacific Coast League Padres. Pitcher Billy McCool, a left-handed reliever, went 3-4 with Cincinnati before military duty halted his season.

The Pirates left 30-year-old pitcher Al McBean unprotected after a 9-12 season, but the former Buc departed with the endorsement of Pittsburgh GM Joe Brown. Squeezed out by Pittsburgh’s plan to protect its younger hurlers, Brown foresaw a big season for McBean in stating, “He still has a great arm and knows how to pitch.”28

After the draft, the differing strategies between the Padres and Expos became readily apparent. Expos GM Jim Fanning gloated that Montreal outperformed its mock drafts.29 The Expos certainly had more familiar names in veterans Maury Wills, Donn Clendenon, Manny Mota, and Jesus Alou. Bavasi mused, “We drafted players who are on the verge of becoming real big leaguers and Montreal drafted a bunch of players who are trying to stay in the majors.”30

Bavasi explained the club’s expansion draft strategy to San Diego Union columnist Jack Murphy: “Our job is to give fans a good show, and I don’t think you can do it with veterans.”31 To hear Leishman comment, it appeared that San Diego got exactly the club it wanted. The Padres general manager said, “The club is tailored to fit a big park such as San Diego Stadium. We wanted speed, pitching, and defense.”32

Notwithstanding the optimism for having executed their draft strategy, Bavasi knew the Padres had holes that required filling. The need for catching experience was particularly acute. In addition to Kendall, the Padres selected “defensive demon”33 Ron Slocum from the Pirates organization. Despite the potential, neither Kendall nor Slocum possessed experience above the Double-A level. Bavasi also specified center field as another spot where the talent level required improvement.

Other clubs inquired about the Padres veterans, with Giusti, Selma, Gonzalez, and McBean attracting interest. Leishman started making deals quickly and he acquired first baseman Bill Davis from Cleveland on October 21. Davis had shown power potential with Portland in 1965 and 1966 before an Achilles injury ended his 1967 season. Satisfied with scouting reports over his comeback in 1968, Leishman made the move.34 Weeks later during the winter meetings, the Padres sent Versalles the other way to complete the deal.

Bavasi attended those same winter meetings in San Francisco with a mission. He stated, “We’ll do something before we leave here … because we have to have a catcher and another infielder.”35 Before striking a trade, the Padres claimed Bobby Klaus through the minor-league draft; Klaus served as the Pacific Coast League Padres’ player-manager after Skinner joined the Phillies.

The discontented Giusti served as the primary trade bait, and on December 3, Bavasi and Giusti both got what they wanted. The Padres sent Giusti back to the Cardinals with four players coming the other way: infielder Ed Spiezio, outfielder Ron Davis, catcher Danny Breeden, and pitcher Phil Knuckles. Spiezio and Davis spent time in St. Louis in 1968 although neither batted exceptionally well. Spiezio arrived, however, with the endorsement of pitching great Bob Gibson, who opined, “All Ed needs to do is play regularly and he’ll be a dangerous hitter. He didn’t get to play much for us.”36

Breeden played 118 games for Tulsa of the Pacific Coast League, “regarded as expert receiver and thrower.”37 Knuckles went 13-6 with a 2.93 ERA with Arkansas of the Double-A Texas League. In a sign that he had achieved his goals, Bavasi claimed, “Now we’re respectable – we could open the season tomorrow with what we have.”38 He rejected Houston’s offer of five players for Ron Davis, who started the 1968 season with the Astros. Bavasi asserted, “Davis is a great center fielder and we needed him.”39

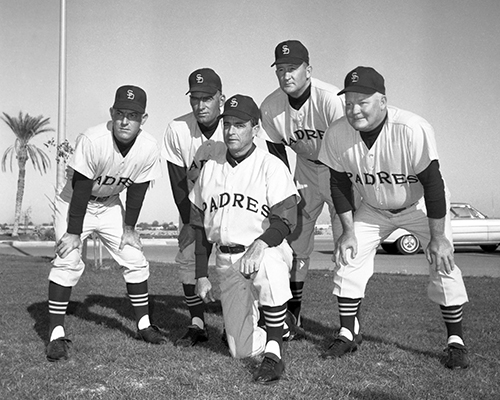

The 1969 Padres’ coaches gather around manager Preston Gomez at their spring training site in Yuma, Arizona. Left to right are coaches Sparky Anderson, Wally Moon, Roger Craig, and Whitey Wietelmann. (Courtesy of Tom Larwin)

Getting the fans to the ballpark

The Padres waited for the Chargers to conclude their 1968 American Football League season before making a concerted push for season-ticket sales. In that department, the Padres were lagging behind their Montreal expansion brethren.

Having focused almost exclusively on business clients, they had sold only 1,500 season tickets, well short of the club’s goal of 4,000. During the launch of the public sales drive, Bavasi pointed out that the Padres’ break-even mark was total attendance of 800,000. He explained, “We can do it because we’re an expansion team, but an established team would need to draw more, because it would have higher-salaried players.”40 He also worked out the math required to make that goal: Average 22,000 in the 18 games against the Dodgers and Giants and attract around 7,000 for each of the other 60 dates on the schedule.41 The Dodgers’ Don Drysdale and the Giants’ Willie Mays assisted the Padres’ efforts by recording radio spots to let San Diegans know they would be visiting during the upcoming season.42

There was some concern that the decision to keep the Padres moniker contributed to tepid ticket sales. Bavasi favored dropping the name, but was overridden by both Smith and apparent fan sentiment.43 Smith’s influence brought around Bavasi as the latter declared, “It’s a beautiful name, very apt and descriptive.”44

The swinging friar logo as well as the brown and gold color scheme debuted in November, and the club unveiled its on-field look in December with DaVanon and Klaus modeling the uniforms. As the 1969 season approached, Bavasi’s initial concerns appeared to be manifested in still disappointing ticket sales. Bavasi explained, “When people see or hear the name Padres they still think of minor-league baseball.”45 He hoped the name would become an asset in time, but for now it seemed like a source of confusion.46

Ticket manager Joe Sullivan would take delivery of 2.8 million tickets ahead of the March 28 opening of the San Diego Stadium box office; as it turned out, the vast majority of the Globe Ticket Company’s output would go to waste.47

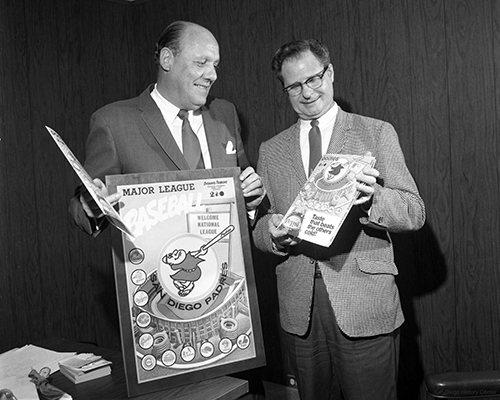

At the annual San Diego sports writers’ dinner artist Eric Poulson shows off the 1969 Padres’ scorecard design while team president E. J. “Buzzie” Bavasi looks on with a copy of the special newspaper page recognizing what will be San Diego’s inaugural major league baseball Opening Day. (Courtesy of Tom Larwin)

Minor-league matters, past and future

As the Padres transitioned from a minor-league club into a major-league organization, there remained past and future minor-league issues requiring attention. To develop players for the National League club, the organization assembled a development structure during the fall of 1968.

On October 31 Leishman announced an agreement with Key West of the Class-A Florida State League. One week later, the Padres agreed to share the new Triple-A team in Omaha with Kansas City; the Royals would operate the club with the Padres supplying a handful of players. Adding an affiliation with Salt Lake City of the rookie Pioneer League and working agreements with Elmira and Waterbury from the Eastern League, the Padres had their farm system for 1969 in place.

Shedding their Pacific Coast League identity would require costly and drawn-out negotiations. The Coast League sought a total indemnity of $1.2 million for the loss of its San Diego and Seattle clubs, with the league apparently using the 1958 indemnity for the losses of Los Angeles and San Francisco as its template. The league was remodeled further during the course of an offseason restructuring that increased the number of Triple-A leagues from two to three.

In addition to losing two cities through major-league expansion, the Pacific Coast League’s Easternmost outposts were incorporated into the revived American Association. The financial dispute lingered throughout the offseason. In January 1969, the Pacific Coast League requested the intervention of outgoing Commissioner William Eckert. Leishman noted that the realigned league would have the advantage of reduced travel costs among member clubs. The Padres and Pilots offered only $30,000 each. The Pilots eventually agreed to a $300,000 indemnity payment on March 25 and, days later, incoming Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ordered the Padres to pay $240,000 to the Pacific Coast League.

Yuma

For their first spring training, the Padres selected Yuma, Arizona, over Mesa-Tempe, Arizona and Imperial Valley, California. The Cactus League seemed a natural fit for the Padres, and the circuit would include seven teams for 1969: San Diego, San Francisco, Oakland, Seattle, California, Cleveland, and the Chicago Cubs. For their first spring training, scheduled to begin on February 22, the Padres used temporary facilities and a remodeled Keegan Field while the City of Yuma built a permanent complex with four fields in time for 1970.

The Padres’ spring schedule was supposed to begin in Mexico City, as the club had agreed to be a last-minute substitute for the Chicago White Sox for three exhibition games against the Tigers and Reds of the Mexican League. The inability to secure visas forced cancellation of the games, but the club agreed to play four games in Mexico City the following spring.

Instead, several days of intrasquad games provided the preparation for the opening of the spring season on March 7 against California. With 2,500 in attendance at Keegan Field, the Padres won their spring debut behind a Bill Davis grand slam and three no-hit innings from the recently signed Johnny Podres.

The dominant theme through spring training became the search for a dependable, major-league-ready catcher. The Padres purchased Jerry Zimmerman’s contract from Minnesota but he ultimately decided to end his playing career and pursue the coaching path. The team even extended an invite to Chris Krug, a catcher formerly of the Cubs’ and Angels’ organizations who had been out of baseball for a year and a half. San Francisco’s Bob Barton, Cincinnati’s Pat Corrales, and Pittsburgh’s Manny Sanguillen were also considered.

Ultimately, the club found their man in the form of a different Pirates catcher. On March 28, San Diego acquired Chris Cannizzaro and pitcher Tommie Sisk from the Steel City in exchange for the previously untradeable Ron Davis as well as the recently acquired Klaus. Bavasi noted that Cannizzaro knew National League hitters, and Sisk would fill the final spot in a rotation currently composed of Selma, Podres, McBean, and Kelley. “We got two things we needed badly,” said Bavasi.48 Bavasi made one final deal before the start of the season, adding reliever Jack Baldschun after his release from Cincinnati.

The big-league Padres take the field

The new San Diego Padres made their National League debut at San Diego Stadium on April 8 against the Houston Astros. Bavasi maintained his optimism about the new venture despite having to revise downward his hopes for a bumper crowd on Opening Day. He commented, “San Diego is either a major-league city or it isn’t. I think it is and I believe I made the right decision.”49

Although the attendance of 23,370 fell short of expectations, the on-field result did not disappoint. At a sportswriters dinner the previous evening, an interaction with Astros starter Don Wilson left Padres starter Selma annoyed. Wilson told Selma, “You know, don’t you, that you’re going to lose tomorrow night?”50

Although Selma allowed the Astros a run in the opening frame, that run was Houston’s last. Scattering five hits and backed by Spiezio’s line-drive home run in the fifth and an RBI double by Brown that scored Pena in the sixth, Selma secured the first win in Padres history, 2-1. In fact, all four expansion teams won their opening games but all predictably struggled during their maiden seasons.

The Padres struggled on and off the field. The final season attendance barely topped a half-million; at 512,970, the Padres drew about 160,000 fewer fans than the Pilots, who moved to Milwaukee in April 1970 after the bankruptcy of the team. Cash flow became an issue as Bavasi admitted later, “There was never a lot of money from the start.”51

On the field, the Padres completed the opening series sweep of the Astros, but finished April at 9-14. During April, inaugural-game winner Selma was traded to the Cubs for pitchers Joe Niekro and Gary Ross and shortstop Francisco Libran.

In May, the Padres took a series from the Cardinals at Busch Stadium, and also traded Bill Davis and local boy DaVanon to St. Louis for pitcher John Sipin and catcher Sonny Ruberto. The move cleared first base for Colbert, who would pace the club in home runs and RBIs. Back-to-back road sweeps in Montreal and Philadelphia took the Padres to 24-30 on June 4, but the team proceeded to drop 31 of its next 36 games to establish a firm hold on the National League West Division cellar.

Podres retired on June 27 to become a minor-league pitching coach. Cannizzaro became the first Padre selected for the All-Star Game, although he did not play. With the team collapsing on the field, attendance followed suit; Buffalo and New Orleans inquired about relocation in July.52

Gomez kept a brave face on results, and his patience was rewarded as the club played spoiler for other divisional contenders.53 The Padres swept the Dodgers in early September, but drew only 35,000 for the four-game series at San Diego Stadium. Later in the month, the Padres took crucial games from the Astros and Reds, and won a three-game series against the Giants that cleared the path for the Braves to take the division crown.

The Padres finished the season at 52-110, the same record as the Expos. In a debut season filled with ups and (a lot of) downs, on and off the field, San Diego was now a major-league city. Questions about that status would persist, but San Diego continues to answer Bavasi’s comment in the affirmative. It’s a major-league city.

JOHN W. BAUER resides with his wife and two children in Parkville, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City. By day, he is an attorney specializing in insurance regulatory law and corporate law. By night, he spends many spring and summer evenings cheering for the San Francisco Giants and many fall and winter evenings reading history. He is a past and ongoing contributor to other SABR projects.

Notes

1 “City Made Its First Move For Majors 10 Years Ago,” San Diego Union, April 7, 1969: X3.

2 Bill Swank, Baseball in San Diego: From the Padres to Petco (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 49.

3 Bob Ortman, “Scouts Are No. 1 on Bavasi’s List of Musts,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1968: 9.

4 David Porter and Joe Naiman, The San Diego Padres Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2002), 6.

5 Jerome Holtzman, “A.L. Vote to Expand Marks 1967 History,” The Sporting News Official 1968 Baseball Guide (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 2002), 167, 169.

6 Dick Kaegel, “Sweating, Waiting … As N.L. Debated,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1968: 5.

7 Ibid.

8 Collier, “Montreal Gets Second Franchise,” San Diego Union, May 28, 1968: C1.

9 Collier, “Whew! S.D. Nearly Missed,” San Diego Union, May 29, 1968: C1.

10 Jack Murphy, “Phone’s Ring Starts Tense Final Hours,” San Diego Union, May 28, 1968: C1.

11 Collier, “Montreal Gets.”

12 “KOGO Will Air Padre NL Games for Next 3 Years,” San Diego Union, July 31, 1968: C1.

13 Frank Exarhos, “Padres, Hahn Reach Stadium Use Accord,” San Diego Union, August 2, 1968: B1.

14 Exarhos, “Board OKs Padre Pacts for Stadium,” San Diego Union, August 6, 1968: B1.

15 Murphy, “That $1 Million Isn’t Bavasi’s But He Feels Quite Prosperous,” San Diego Union, August 15, 1968: C1.

16 Murphy, “The Long Wait Is Over – Gomez Is Bavasi’s Man,” San Diego Union, August 30, 1968: C1.

17 Collier, “Padres Name Preston Gomez to Manage 1969 NL Team,” San Diego Union, August 30, 1968: C1.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 “Signing of Anderson Completes Pad Staff,” San Diego Union, September 27, 1968: C1.

21 Murphy, “Buzzie Buys Name Padres After Hearing From a Certain Source,” San Diego Union, September 29, 1968: H1.

22 Hernandez’s page on baseball-reference.com includes only a single at-bat in 1969 for Salt Lake City of the Pioneer League.

23 “San Dieguito High Star Padres’ First Major Draft Choice,” San Diego Union, June 7, 1968: C1.

24 Murphy, “Buzzie Buys Name.”

25 Ibid.

26 Paul Cour, “Padres Placing High Hopes on Big Bill Davis,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1968: 51.

27 Collier, “Padres Launch.”

28 Cour, “Padres’ Plum Is Homegrown DaVanon,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1968: 51.

29 Collier, “Expos’ Warm Draft Leaves Bavasi Cold,” San Diego Union, October 15, 1968: C4.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Porter and Naiman, 6.

33 Collier, “Padres Stress Youth, Speed; Avoid Older Stars in Draft,” San Diego Union, October 15, 1968: C1, C4.

34 Ibid.

35 Collier, “Padres Get Cleveland’s Davis in Delayed Swap for Versalles,” San Diego Union, October 22, 1968: C3.

36 Collier, “Padres Weighing Trade Possibilities as Winter Meetings Get Underway,” San Diego Union, December 2, 1968: C2.

37 Howard Hagen, “22-Foot Putt On Playoff Hole Does It,” San Diego Union, February 17, 1969: C1, C4.

38 Collier, “Padres Deal Giusti for 4 Young Cards,” San Diego Union, December 4, 1968: C1.

39 Ibid.

40 Collier, “Padres Reject Astros’ Offer for Ron Davis,” San Diego Union, December 6, 1968: C1.

41 Collier, “Padres Launch Season Ticket Drive,” San Diego Union, January 21, 1969: C1.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Murphy, “Buzzie Buys Name.”

45 Ibid.

46 Murphy, “San Diego Has Disbelievers but Bavasi Isn’t Among Them,” San Diego Union, March 28, 1969: C1.

47 Ibid.

48 “Padre Ducats Arrive in Big Bundle,” San Diego Union, March 13, 1969: E4.

49 Collier, “Pads Bolster Catching, Mound,” San Diego Union, March 29, 1969: C1.

50 Murphy, “San Diego Has Disbelievers.”

51 Collier, “Padres Sparkle in Debut, Selma Beats Astros, 2-1,” San Diego Union, April 9, 1969: C1.

52 Porter and Naiman, 9.

53 Porter and Naiman, 14.

|

SAN DIEGO PADRES EXPANSION DRAFT |

|||

|

PICK |

PLAYER |

POSITION |

FORMER TEAM |

|

1 |

Ollie Brown |

of |

San Francisco Giants |

|

2 |

Dave Giusti |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

3 |

Dick Selma |

p |

New York Mets |

|

4 |

Al Santorini |

p |

Atlanta Braves |

|

5 |

Jose Arcia |

ss |

Chicago Cubs |

|

6 |

Clay Kirby |

p |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

7 |

Fred Kendall |

c |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

8 |

Jerry Morales |

of |

New York Mets |

|

9 |

Nate Colbert |

1b |

Houston Astros |

|

10 |

Zoilo Versalles |

ss |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

11 |

Frank Reberger |

p |

Chicago Cubs |

|

12 |

Jerry DaVanon |

3b |

St. Louis Cardinals |

|

13 |

Larry Stahl |

of |

New York Mets |

|

14 |

Dick Kelley |

p |

Atlanta Braves |

|

15 |

Al Ferrara |

of |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

16 |

Mike Corkins |

p |

San Francisco Giants |

|

17 |

Tom Dukes |

p |

Houston Astros |

|

18 |

Rick James |

p |

Chicago Cubs |

|

19 |

Tony Gonzalez |

of |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

20 |

Dave Roberts |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

21 |

Ivan Murrell |

of |

Houston Astros |

|

22 |

Jim Williams |

of |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

|

23 |

Billy McCool |

p |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

24 |

Roberto Pena |

2b |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

25 |

Al McBean |

p |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

26 |

Rafael Robles |

ss |

San Francisco Giants |

|

27 |

Fred Katawczik |

p |

Cincinnati Reds |

|

28 |

Ron Slocum |

3b |

Pittsburgh Pirates |

|

29 |

Steve Arlin |

p |

Philadelphia Phillies |

|

30 |

Cito Gaston |

of |

Atlanta Braves |