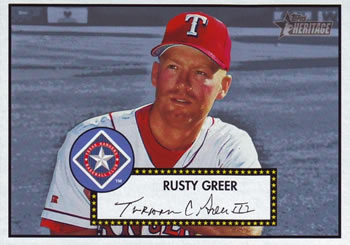

Rusty Greer

On July 28, 1994, Texas Rangers left-hander Kenny Rogers had been perfect for eight innings and needed three more outs to make baseball history. A crowd of 46,581 fans was standing and cheering at the brand-new Ballpark in Arlington as Rogers warmed up to face the bottom third of the Angels’ order.

Rookie outfielder Rusty Greer took his spot in center, played catch with left fielder Juan Gonzalez and felt pretty much the same thing most fielders felt with a perfect game on the line.

“I didn’t want the ball hit to me and I wasn’t the only one,” Greer said.1

Second baseman Rex Hudler was the first batter, and Rogers got ahead 0-2 in the count. Rogers then threw a fastball and Hudler hit a looping line drive falling fast in right-center.

“When the ball was hit, I took off and said, ‘I’m going to have to dive for this,’ Greer said. “As I get halfway there, I said, ‘I know I am going to have to dive for this ball.’ I got three-quarters there and I said, ‘I’m going to catch this ball. As I left my feet, I said, ‘I’ve got it’”2

Greer made an all-out dive for a back-handed catch as the crowd erupted and Rogers broke into a smile on the mound. Two outs later, Rogers had his perfect game.

The play remains an iconic moment in Ranger history. It is also a defining moment in the nine-year career of a red-headed outfielder from Albertville, Alabama, who became one of the Rangers’ most beloved players because of his hustling all-out style.

Greer was the Rangers starting left fielder during a memorable four-year stretch in 1996-99 when they won the first three division titles in club history. Greer wasn’t the most talented or intimidating player on a team that included Gonzalez, catcher Ivan Rodriguez, second baseman Mark McLemore, designated hitter Mickey Tettleton, first basemen Will Clark and Rafael Palmeiro and third basemen Dean Palmer and Todd Zeile. Greer had average speed and power, and a below average throwing arm.

But he knew how to hit and loved playing defense, especially when he dove or crashed into the fence to rob somebody of a hit. Greer never made an All-Star team but batted third in a powerful, star-laded lineup, hitting over .300 and annually both scoring and driving in 100-plus runs. With his red hair and freckles, Southern drawl and genuine aw-shucks honesty, it was easy for Rangers fans to fall in love with “The Red Baron,” as broadcaster Mark Holtz termed him.

“Rusty wasn’t a high draft choice,” Former Rangers general manager and now-broadcaster Tom Grieve said. “He earned every minor league promotion. Played hard and hustled all the time. Diving plays. Most importantly he was an excellent player. Other guys on the team were more highly regarded, especially nationally, but our fans really appreciated his style and blue-collar attitude.”3

Greer’s style earned him admiration and respect. It also exacted a toll over the years. Greer’s ambition was to play until he was 40. But he was just 33 when he appeared in his final game, his body no longer able to hold up to the constant pounding. Long after Greer retired, he was still answering the same question over and over again.

Did he have any regrets on how much he punished his body and ended up shortening his career?

“Yes, to an extent,” Greer said. “I do believe I could have played longer. But no, because I had the respect of my teammates, the media, the fans, my peers. There is nothing more satisfactory than taking a hit away or keep a run from scoring. Playing in the outfield, it is inherent, you have to dive, you have to run into a wall.

“I don’t regret it. Would I have done things differently? Maybe. But the respect was what I was after. If the ball was going to get close to me, I was going to try and catch it. That’s what my attitude.”4

Thurman Clyde “Rusty” Greer III was born on Jan. 21, 1969, to T.C. and Marty Greer in Fort Rucker, Alabama. Located in the southeast corner of the state, Fort Rucker is the United States Army Aviation Center with multiple airfields used for helicopter and small airplane training. T.C. Greer spent his tour in Vietnam as a “medevac dust-off guy,” a term for helicopter crews who flew into hot combat zones and removed wounded soldiers.

“My dad was in the military, flew helicopters in Vietnam, which I am super proud of,” Greer said. “Did that for 13 months. ’69 to ’70.”5

Many years later, long after he retired, Greer heard first-hand testimony what his father did in Vietnam. It came one night when Greer was at a Rangers Christmas event, signing autographs for fans in Fort Worth’s downtown Sundance Square.

There was a long line of fans waiting to get Greer’s autograph. Finally, an elderly man approached wearing a Vietnam Veteran’s baseball cap. Greer greeted him respectfully and the two struck up a conversation.

“How are you sir?” Greer asked. “Are you a Vietnam vet guy?

“Yeah,” the man replied.

“What can I get you” Greer said hospitably. “We have cards and everything.”

“Nothing.,” the man said. “You the one they call Rusty?”

“Yes sir,” Greer said.

“Your dad, T.C. Greer?”

“Yes sir.

“He saved my life one day south of Saigon,” the man said. “We were in a firefight, he came and picked me up. I don’t know how he got in and got me on a helicopter, but he got me out. Tell him I said, ‘Thank you.’”

The man turned and walked away.

“It brought me chill bones because I’d never seen that guy in my life,” Greer said. “I was like Holy….”6

Greer’s father thought about making the military his career but instead went into the saw mill and lumber business, first in Georgia and then in Albertville. Greer and his younger sister Anna grew up in the small northern Alabama town known for its fire hydrant manufacturing plant.

Greer grew up playing baseball and basketball. Surprisingly, basketball was his favorite sport at Albertville High and the one he really worked at year-round. Baseball got his attention only in the spring when basketball was over.

“I was a point guard in basketball,” Greer said. “That was the sport I wanted to play. I loved basketball and I was pretty good at it. I had some scholarship offers to play junior college. That was where my scholarship offers were. They told me if I wanted to play baseball, I could, but that was my secondary sport.”7

Greer had a neighbor, Norman Darden, in Albertville who was attending Montevallo College, a couple hours south near Birmingham. He told Doug Sisson, the Montevallo assistant baseball coach, there was a high school senior in his hometown who was worth at least a tryout. Sisson contacted Greer and invited him to come to Montevallo to try out with seven or eight other players.

“I was kind of behind the eight ball because I really didn’t practice baseball,” Greer said. “It kind of came natural to me.”8

Greer worked out for Sisson and Bob Riesener, the Falcons legendary head coach who would retire with 1,045 wins. Greer impressed them enough to be offered a baseball scholarship to Montevallo. Sisson would later coach Greer in the Rangers farm system.

Greer had a great freshman year, hitting .451 with seven home runs and 54 RBIs. He struggled as a sophomore, hitting just .320 and at one point was benched. But Greer came back strong as a junior in 1990, hitting .412 with 16 home runs. He was first-team NAIA All-American and Rangers scout Rudy Terrasas was following him closely.

“Doug Sisson called me and said, ‘There’s a guy at Montevallo you need to watch play,’” Terrasas said. “I did and Rusty stood out. I really did my homework on him. He checked all the boxes I look for in a hitter.”

Scouting director Sandy Johnson and his scouting supervisors Doug Gassaway and Bryan Lambe went to see Greer as well. By the time they were done, the Rangers were ready to grab Greer as early as the fourth round.

“Sandy loved him,” Terrasas said. “I said, ‘Slow down. Nobody else is on this guy. You can wait.”9

Johnson listened to Terrasas’ advice and held off through the first nine rounds.

“If somebody grabs this guy, you’re fired,” Johnson told Terrasas.10

Finally, the Rangers took Greer in the 10th round of the 1990 draft. Considering the round and what the Rangers got in return, it may have been their best draft pick in club history. Greer received $22,500 for a signing bonus.

After two strong seasons in Class A, Greer began 1992 at Double A Tulsa and wasn’t quite as stellar, hitting .267 with a .393 slugging percentage over 106 games.

“I kind of did some soul searching after that,” Greer said. “I’m not going to say I was the most focused person in 1992. I said, ‘Do you really want to do this or not.’”11

At that point, Greer was not considered one of the Rangers’ top prospects. That changed in 1993 when Greer went back to Tulsa. This time he played in 129 games and hit .291 with 15 home runs, 59 RBIs, a .365 on-base percentage and a .461 slugging percentage.

“I loved the minor leagues.,” Greer said. “There were guys with more talent than me but I was what they called a ‘grinder.’ I didn’t mind getting on the bus. This was my job. If I just go do my job, I am going to get a chance at some point. I wouldn’t trade the minor leagues for anything.”12

Greer earned a late-season promotion to Triple-A Oklahoma City for the 89ers’ final eight games and then was selected for the Arizona Fall League. Playing against top prospects, Greer hit .333 with two home runs and 23 RBIs in 36 games.

Rangers manager Kevin Kennedy saw Greer play in Arizona and said he wanted the left-handed hitting outfielder added to the 40-man roster. Kennedy saw him as a legitimate prospect who could compete for a job in spring training.

The Rangers went to Florida with an opening in right field. They had Gonzalez in left coming off two straight home run titles and speedy David Hulse in center. Jose Canseco, who had been the Opening Day right fielder in 1993, was limited to designated hitter while recovering from elbow surgery. Right field was open and Greer was among the candidates.

The competition included veteran right-handed hitters Chris James, Gary Redus and Butch Davis while Rob Ducey, Dan Peltier and Oddibe McDowell joined Greer from the left side. Greer was the only candidate who had yet to play in the majors.

James and Redus both appeared to be locks to make the team, either as a right-handed platoon or fourth outfielder. The Rangers’ need was a left-handed bat to either win the job outright or as a left-handed platoon partner.

Greer was the last player cut in spring training. Ducey, a seven-year veteran, won the right field job and Greer was optioned to Triple-A Oklahoma City. That hardly settled the issue. Ducey hit .172 in 11 games while injuries took out Redus and McDowell.

Greer was called up to the big leagues on May 16 and entered the lineup that night in Oakland, batting second and playing right. He flied out in his first at-bat against Oakland starter Bob Welch. The Rangers still scored six runs that inning, so Greer came up against right-handed reliever Carlos Reyes in the second and launched a full-count pitch to deep right for his first major-league career home run.

“Yeah, I’ll never forget that one,” Greer said.13

There would be no going back to Oklahoma City. Greer enjoyed a terrific rookie season, batting .314 with 10 home runs and 46 RBIs. Two of those home runs came in one game against the Blue Jays on July 21, with the first one being an inside-the-park job.

In a season cut short by the players’ strike, Greer had the highest batting average and on-base percentage among all rookies with at least 300 plate appearances. His .487 slugging percentage was fourth, and he finished third in the American League in Rookie of the Year voting behind Bob Hamelin of the Royals and Manny Ramirez of the Indians.

The season ended strangely for the Rangers. They were in first place when the players walked out on Aug. 11, but their record was only 52-62. The season ended up being cancelled and Kennedy and general manager Tom Grieve were both fired. They were replaced by general manager Doug Melvin and manager Johnny Oates, both coming over from the Orioles.

Melvin and Oates were unsure about Greer, who could also play first if needed. Clark was the first baseman and Melvin addressed center field by acquiring fleet-footed Otis Nixon from the Red Sox for Canseco. The Rangers needed another corner outfielder to go with Gonzalez, but Greer did not come with the big power bat associated with either left or right.

When spring training opened, Oates announced there were two openings in his lineup. One was in right field, and the other was at second base, even though Jeff Frye had hit .327 as a second-year player in 1994.

“Where I got confused was in spring training,” Greer said. “I was third in the Rookie of the Year voting, hit .314, played well. Jeff Frye had done well. Johnny said, ‘I have two spots open, one outfield spot and second base’. I’m looking around and I said, ‘Wait a minute. I performed well; do I not even get a chance to make the team?

“What I didn’t know then but figured out later, Johnny Oates was a veteran manager. With him, young guys need to pay their dues. But once you show you are a guy, he’ll put the saddle on and ride you. That’s what I did.”

In his second season in the majors, Greer had to fight the perception that he was just a platoon player. It didn’t help that Greer hit .246 with a .346 slugging percentage against left-handers that season as opposed to .277 and .442 against right-handers.

But Greer was gaining another reputation, that of being a batter who came through with some big hits. On April 29, he delivered an RBI single in the bottom of the ninth to give the Rangers a 6-5 victory over the Indians.

During his career, Greer drove home the winning run in the Rangers’ final at-bat in 17 games. Most memorable was the night of June 8, 1995, when the Rangers trailed 8-1 going into the bottom of the eighth inning before rallying to win. Greer finished off the memorable comeback with a walk-off home run in the bottom of the 10th inning and the Rangers’ 10-9 victory is generally considered the greatest comeback win in club history.

“When you are hitting in the third spot, you come up in those situations a lot,” Greer said. “I was not always successful. I remember taking a 3-2 fastball that cut the plate off Rick Aguilera with a runner on second base that could have tied the game. Strike three, game over.

“I was put in those situations a lot. The situation can’t get too big. So, what is my job? My job is to pass the baton to the big dogs behind me. Juan Gonzalez, one of the best RBI guys to ever play the game. Let’s be honest. Who do you want to face? Him or me. I would say me. I got a lot of good pitches to hit, and that helped.”14

Greer had a streaky season and finished hitting .271 with 13 home runs and 61 RBIs. He had also done something else. He had gained Oates’ confidence. The manager had seen enough to believe Greer was ready to be a full-time player regardless of who was on the mound.

The Rangers, coming in third place in the AL West, finished a 74-70 season with a 9-3 win over the Mariners. When the game was over, Oates and Greer walked up the tunnel to the clubhouse together. Once they got there, Oates pulled Greer aside.

“You’re not a platoon player,” Oates said. “You’re an everyday player. Next year I’m going to switch you and Juan. You’re going to be my left fielder.”15

The move made sense. It allowed the Rangers to take advantage of Greer’s better speed and athleticism in the Ballpark’s spacious left field. Gonzalez had the superior throwing arm needed in right field.

Both players flourished under the arrangement. The next four years were the best of Greer’s career as he helped the Rangers win three division titles. It all began in 1996, one of the most memorable seasons in club history, when the Rangers broke through and won their first ever division championship.

Greer hit a career high .332 with 18 home runs, 100 RBIs, a .397 on-base percentage and a .530 slugging percentage. His penchant for big hits continued with a game-winning single in the top of the 10th against the Orioles on April 28 and a game-winning home run in the top of the 10th against the Indians on August 21.

Greer also proved to be an excellent defensive player. He saved Darren Oliver’s 2-0 victory over the Blue Jays on June 8 with two terrific ninth-inning catches against Joe Carter and Charlie O’Brien.

The fans loved how Greer was willing to sacrifice his body to make a play. It was a mentality he learned from veteran first baseman Will Clark. The two had lockers next to each other in the clubhouse and Greer learned much from his All-Star teammate who played the game with unrelenting intensity.

“Will told me you might feel like you can’t play,” Greer said. “But if your team needs you, you go out and play until something blows out. If you think about Will, that’s how he played, broken toe, hurt elbow whatever. He sacrificed numbers because his elbow was hurt but he felt he was better than the next option.”16

Greer said there was one night where he told Oates that he might need a night off.

“I said, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to be able to play,’” Greer said. “My back was hurting, my hamstring, something. He said, ‘Let me tell you something, we need you hitting third.’ That’s all he said. Turned and walked away.”17

The Rangers were in Cleveland on May 18 when Greer crashed into the outfield wall making a great catch on Eddie Murray’s long drive. He suffered a sprained left shoulder and missed the next 10 games. That was an example of what Greer was doing to his body.18

Greer played in 139 games, hitting .332 with 96 runs scored, 18 home runs and 100 RBIs. Gonzalez won American League MVP honors by driving in 144 runs batting behind Greer and the Rangers won their first division title.

Their first-round opponents were the New York Yankees, who were looking for their first World Series title since 1978. This was the beginning of the Yankees dynasty under manager Joe Torre, and the Rangers almost knocked them off, losing the best-of-five series in four close games. The Rangers won the opener, and then lost two games by one run before losing 6-4 in the final game.

Greer was 2-for-16 with three walks in the series and just missed delivering a big hit in a 3-2 loss in Game Three. Yankees center fielder Bernie Williams hit a home run in the top of the first inning to give his team a 1-0 lead. Greer came up in the bottom of the inning against Key and launched a drive to deep center that was headed over the wall. But Williams leaped up and snatched it to take away a home run.

“When I first hit it, I said, ‘I got it.’” Greer said. “I think if that ball had cleared the wall. I am not saying it would have turned out different but it would have given us a little bit of a spark. It certainly would have helped me because I didn’t swing the bat well. To me that was a huge play in that series.”19

Greer had another strong season in 1997 but the Rangers’ pitching fell apart and the club struggled to a 77-85 record. Greer hit .321 with 112 runs scored, 42 doubles, 26 home runs, 87 RBIs, a .405 on-base percentage and a .531 slugging percentage.

After the season, Greer finished in 22nd place in the American League Most Valuable Player voting. It was a rare glimmer of recognition. From 1996-99, Greer combined to hit .315, ninth best in the American League in that stretch. He was one of 15 players with at least a .900 OPS or better. Yet he was constantly overshadowed by other teammates. Greer never did play in an All-Star Game or even get selected as the Rangers Player of the Year.

In 1998, the Rangers rebuilt their pitching around starters Aaron Sele and Rick Helling, and closer John Wetteland and once again won the ALWest. Gonzalez won a second American League MVP Award and Rodriguez continued to establish his reputation as the best catcher in baseball.

Greer did his part in the number three spot, hitting .306 with 107 runs scored, 16 home runs and a career-high 108 RBIs. He hit .337 against lefties and a game-winning home run in the 13th inning against the Yankees on May 14 added to his reputation for the big hit.

The Rangers won the division with 88 victories but were overmatched in the Division Series against the Yankees, who set an AL record with 114 wins. The Rangers were swept while scoring one run over three games. Greer went 1-for-11.

The Rangers lineup underwent a significant change in 1999 when Clark left as a free agent and was replaced by Palmeiro. Greer remained in the No. 3 spot in a lineup that scored 945 runs, the most in Rangers history. Greer’s numbers were as good as ever as he hit .300 with 107 runs, 20 home runs and 101 RBIs.

The Rangers won the division title with 95 wins, and appeared better prepared to face the 98-win Yankees in their third post-season meeting. There was one disconcerting mishap in September. The Rangers were in Kansas City on September. 13 when Greer was hit in the face by a thrown ball.

Greer was shagging fly balls during batting practice while pitchers Rick Helling and Aaron Sele played long toss in the vicinity. Greer blamed himself for what happened next, saying that he forgot to use what he calls “diamond awareness.”

Palmeiro hit a high pop into shallow left. Greer came in, made the catch and turned to throw the ball back in when he heard someone yell, “Look out!”

“Rick had cut one loose from 90 feet and hits me,” Greer said. “Hits me right in the bridge of my nose and my eye. The first thing I think is my eye is gone. Because my eye was black. Rick felt awful.

“It was my fault. I should have known these guys were playing catch and should have known what they were doing and where. I didn’t have to go and catch that ball. I lost what they were doing. I was scared to death. Forget baseball, I didn’t want to lose my eye.”20

Greer suffered a broken nose and bruised retina. He missed six games with blurred vision and tried to play on September 21, but he left the game after four innings when he continued to have problems with his vision.

Greer returned on September 24 and over his final seven games, Greer went 9-for-28 with a home run, six RBIs and three walks. But on October 1, in the opener of the Rangers’ season-ending series against the Angels, Greer had to leave in the seventh inning after reliever Mike Holtz hit him in the left elbow. Greer, with the division already clinched, sat out the final two games.

The Division Series against the Yankees was another disappointment for Greer and the Rangers. Again, their offense disappeared completely, scoring just one run in three games. Because of both the eye and the elbow, Greer was far from being at his best.

“No,” Greer said. “Wasn’t even close. Obviously, I could go out and play and do what I normally do but at the same time, you’re battling an eye deal that just happened and an elbow deal that just happened.”

The Rangers were swept in three games and Greer went 1-for-9. Overall, he was 4-for-36 in his postseason career, and that still bothers him.

“Frustrating,” Greer said. “Bad frustrating. Because I wasn’t good. Let’s call it what it is. The problem is I was counted on to be good. And if I had been what I had been, it would have helped matters. You don’t think I was struggling? It’s extremely frustrating. We had the offensive team to beat anybody.”21

Greer was 31 when the 2000 season opened. He was still a threat at the plate but injuries started taking their toll. On April 15, Greer went on the disabled list for the first time in his career with a strained left hamstring. One day later, he underwent surgery to have bone chips removed from his right ankle. It was an injury that occurred in Triple-A back in 1994 when Greer crashed into the outfield wall right before he was called up to the big leagues.

Greer taped the ankle, battled through it and for a time the problem went away. But in 2000, the ankle started bothering him again and Oates told Greer to get surgery. He didn’t return to the lineup until May 27. Greer also missed the final nine games with plantar fasciitis.

Despite his recent history of injuries, the Rangers still had faith in Greer. When Greer reported to spring training in 2001 for the final year of his contact, the Rangers showed their confidence in him by signing Greer to a three-year, $21.8 million contract extension, with a club option for 2004.”

Greer played in just a combined 113 games in 2001-02 because of more injuries and surgeries and then missed the entire 2003 season. His list of medical operations included surgery to fuse the C5/C6 vertebrae in his neck, Tommy John elbow reconstruction and a torn left rotator cuff.

Greer kept hoping he could return to the field but finally announced his retirement in 2005. As of 2021, Greer said he underwent a total of nine surgeries to correct issues that resulted from his hard-nosed style of play.22

“I wanted to play until I was 40,” Greer said. “My heart wanted to but my body said no.”23

Since retirement, Greer has dabbled in some business ventures and did a weekly spot on an all-sports radio station. But mostly he has stayed busy as a baseball instructor. He was an assistant coach at Texas Wesleyan University for a year and coached in the Texas Collegiate Summer League.

He and his wife Lauri, as of 2021, made their home in the Fort Worth suburb of Colleyville raising their three children: older son Clayton (born in 1999), son Mason and daughter Taylor, twins who were born in 2000. Lauri is from Boaz, Alabama, near Albertville. She also attended Montevallo and they were married on Dec. 2, 1994. Greer coached his sons in youth baseball and runs the Rusty Greer Baseball School. The instructional sessions are dedicated strictly to improving defensive skills.24

The school’s website has a photo of Greer making a diving catch at the Ballpark. The ball was hit by Royals third baseman Dean Palmer. It was the last one he made.

“That was the one that killed me,” Greer said. “But my job was never to stop. My job was to catch the ball. I wasn’t afraid of getting hurt. If you are afraid of getting hurt, you are going to get hurt. I am going to play the way I play.”25

After all these years, Greer still misses the game and is reminded of something former Rangers catcher Jim Sundberg told him.

“Jim Sundberg said, major league baseball starts with a cookie,” Greer said. “You either eat all that cookie or you don’t. When you eat all that cookie, you’re content, you are happy and you are good. When you don’t get to finish the cookie, there is still that feeling…and I didn’t get to finish my cookie. There are still a couple of bites left.”26

Last revised: June 24, 2021

Sources and acknowledgments

TR Sullivan covered the Rangers for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and MLB.com for 32 years, including the entirety of Greer’s career. He has interviewed Greer numerous times, including a 90-minute session at his house in Colleyville on April 27, 2021, specifically for this story.

Sullivan also spoke with former Rangers GM Tom Grieve and scout Rudy Terrasas (now with the Mets) for this story, which was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

All statistics and other factual information came from the Rangers media guides and baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Rusty Greer, interview with TR Sullivan, April 27, 2021 (hereafter Greer interview).

2 Greer interview.

3 Tom Grieve, interview with TR Sullivan, April 29, 2021.

4 Greer interview.

5 Greer interview.

6 Greer interview.

7 Greer interview.

8 Greer interview.

9 Rudy Terrasas interview with TR Sullivan May 3, 2021.

10 Terrasas interview.

11 Greer interview.

12 Greer interview.

13 Greer interview.

14 Greer interview.

15 Greer interview.

16 Greer interview.

17 Greer interview.

18 Rangers media guide.

19 Greer interview.

20 Greer interview.

21 Greer interview.

22 Greer interview.

23 Greer interview.

24 Greer interview.

25 Greer interview.

26 Greer interview.

Full Name

Thurman Clyde Greer

Born

January 21, 1969 at Fort Rucker, AL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.