July 3, 1877: Louisville’s Charley Snyder becomes first major leaguer to wear a catcher’s mask

Invented by Harvard College baseball nine captain Fred Thayer, the first catcher’s mask was a brass and leather contraption first worn by Crimson catcher Jim Tyng in the early spring of 1877.1 By mid-April, both Boston’s Wright Brothers store (owned in part by Red Stockings manager Harry Wright and his brother George) and Chicago’s A.G. Spalding and Brothers (a sporting goods company headlined by White Stockings manager-captain-first baseman Al Spalding), were offering copies for sale.2 Amateur ballplayers were the first to follow in Tyng’s footsteps, often drawing ridicule for wearing a device considered cartoonish or, even worse, dehumanizing.3

Invented by Harvard College baseball nine captain Fred Thayer, the first catcher’s mask was a brass and leather contraption first worn by Crimson catcher Jim Tyng in the early spring of 1877.1 By mid-April, both Boston’s Wright Brothers store (owned in part by Red Stockings manager Harry Wright and his brother George) and Chicago’s A.G. Spalding and Brothers (a sporting goods company headlined by White Stockings manager-captain-first baseman Al Spalding), were offering copies for sale.2 Amateur ballplayers were the first to follow in Tyng’s footsteps, often drawing ridicule for wearing a device considered cartoonish or, even worse, dehumanizing.3

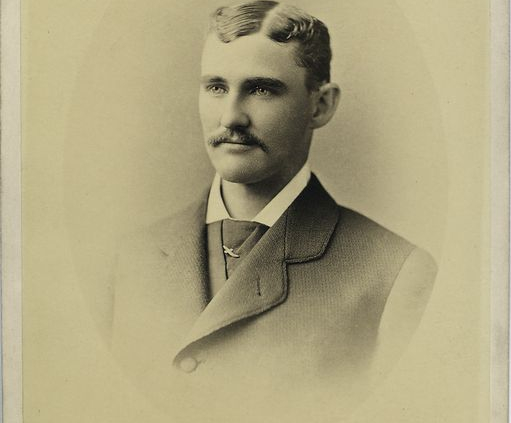

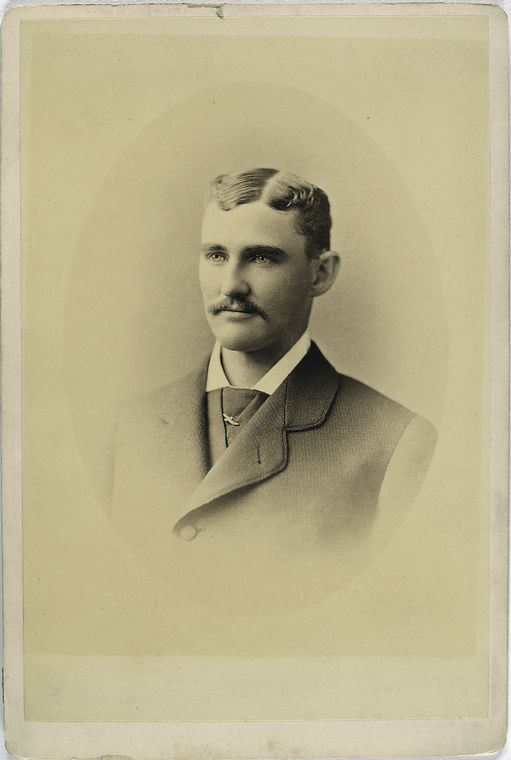

Still, the masks reached major-league competition by the summer of 1877. When one of the National League’s top catchers, 22-year-old Charley Snyder of the Louisville Grays, later known as “Pop,” wore a mask in the Grays’ 6-3 win over the Cincinnati Reds on July 3, he became the first major leaguer documented to have worn a catcher’s mask in a league game.

In the preceding week, Snyder had suffered a split finger from a foul tip in one game after having been knocked down in an earlier match by a foul tip to the face, off the bat of George Wright.4 Those close calls may have pushed Snyder to give his mask a try. It’s entirely plausible that Wright sold Snyder on wearing a Wright Brothers mask after sending him sprawling.

The only direct evidence of Snyder wearing a mask against the Grays was in the Chicago Tribune, whose July 4 issue concluded a summary of the Louisville-Cincinnati league match with the following observation: “Snyder appeared in the Harvard wire-mask.”5

Somehow, Snyder’s mask-wearing escaped attention in Louisville and Cincinnati newspapers. Circumstances surrounding the July 3 match may explain why. It was the first league game played by a reorganized Cincinnati franchise coming back from oblivion.

Cincinnati had finished dead last in the NL’s inaugural season of 1876, and insufficient funds drove Reds owner Josiah L. Keck to disband the once-again last-place Reds in mid-June of the league’s second campaign. A consortium of Cincinnati businessmen was able to retain the franchise in the city.6

Seventeen days since their last match, the Reds were back in action against Louisville. Controversy swirled for months over whether league standings should reflect matches played against the “new” or original Reds, but for now league officials and club owners were thrilled to no longer limp along with a five-team league.7

With time enough for just a few hours of practice together, the new Reds welcomed the Grays back to Avenue Grounds to pick up where they’d left off. The two teams had just completed the opener of a three-game series there, an 8-4 win by Louisville on June 16, when Keck pulled the plug.

A crowd of nearly 1,000 was on hand the first Tuesday in July, serenaded by the sounds of carpenters hammering and sawing on the roof of the ballpark throughout the game.8 Cincinnati featured a battery making their Queen City debut: pitcher Candy Cummings, a curveball maestro who’d been pitching for the Live Oaks of Lynn, Massachusetts; and Scott Hastings, a veteran catcher from the International Association Guelph (Ontario) Maple Leafs, who’d spent most of the previous season roaming the outfield for Louisville.9

In a precursor to the color-coded uniform scheme that the entire NL tried five years later,10 each Red wore differing “parti-colored caps”: red for Cummings, white for Hastings, with the rest of the team sporting blue, green, striped, or multi-colored versions. Surely none of them were pleased to read in the next day’s Cincinnati Enquirer that they “[looked] cute.”11

Opposite Cummings and Hastings, Louisville had its own curveballer, Jim Devlin, the only pitcher the Grays would use all season, and Snyder. The Grays scored first, when stocky Jumbo Latham reached on a third-inning error, stole second, and came home on a Devlin single.

The Reds proved unable to break through against Devlin until the sixth, when Jack Manning scored on an extra-base hit to left-center field by Charley Jones, tying the game, 1-1. (Only three days earlier, the Cincinnati slugger had been returned from the Chicago White Stockings, who’d “borrowed him” for two games after the original Reds went belly-up.) According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, Jones reached third on the play for a triple, but was tagged out by Louisville third baseman Bill Hague, who shoved Jones off the bag. Accounts in several other newspapers credited Jones with a double.

The Grays retook the lead in the bottom of the sixth, with George (later known as Orator) Shaffer scoring from third after doubling to left and moving to third on a sacrifice; driven in by either a Snyder single (according to the Enquirer) or a Haldeman groundout (according to the Cincinnati Commercial). Down 2-1, the Reds rallied in the top of the seventh. After Devlin retired the first two batters, Hastings singled and Will Foley reached on an error by the newest Gray, second baseman John Haldeman.

A newspaper reporter for the Louisville Courier-Journal, Haldeman had been drafted to play in this game by Grays manager Jack Chapman when regular shortstop Bill Craver came up sick. An amateur first baseman in his spare time, Haldeman was the son of Walter Haldeman, owner of the Grays and president of the Courier-Journal. Chapman moved regular second baseman Joe Gerhardt to shortstop and put his boss’s son at the keystone corner. This proved to be the only official major-league game in which Haldeman appeared.12

After Haldeman’s seventh-inning miscue, a walk to Cummings loaded the bases for the next batter, Lip Pike. A three-time National Association home-run champ, albeit with only 15 round-trippers in those three years, Pike clubbed a Devlin offering down the right-field line, circling the bases as the ball disappeared between “the inside and outside fence.”13 After Louisville protested, umpire William Walker ruled the ball foul. Pike regrouped and singled to left, scoring Hastings and Foley to put Cincinnati up, 3-2.

“Hope ran high in the breasts of the friends of the Cincinnati club,” commented the Cincinnati Gazette,14 but not for long. In the Louisville eighth, Cummings made what the Enquirer called “a vital mistake.” Throwing slow curves, he loaded the bases with nobody out and Gerhardt cleared them with a double to left-center. Cummings went back to “his old pace” but the damage was done.15 A fly ball hit by either Snyder (according to the Gazette) or Haldeman (according to the Cincinnati Commercial) brought Gerhardt home to make the final score 6-3.

Snyder, who collected a pair of singles and two RBIs, allowed one passed ball and probably threw a runner out attempting to steal second.16 Most consequentially, he became the first documented big-league catcher to wear a mask in a game.

Several baseball references identify Pete Hotaling of the League Alliance Syracuse Stars as likely the first professional ballplayer to wear a mask in competition, and Mike Dorgan of the NL’s St. Louis Brown Stockings as the first (or “perhaps the first”) to wear one in a major-league contest.17 Hotaling probably first played in a catcher’s mask on July 10,18 while Dorgan definitely did so on August 8, against Louisville.19

Two weeks after the latter game, the Cincinnati Enquirer echoed and then challenged a claim that Dorgan was first to don a mask in a league game. “This is a mistake of about four or five weeks. Both Snyder and Hastings,” the Enquirer asserted, referring to Louisville’s Charley and Cincinnati Red Scott Hastings, “wore the mask and found it a failure before Dorgan ever saw one.”20

Indeed, Hastings wore a mask when facing Hotalings’ Stars on July 13, and, according to a Cincinnati Commercial game summary, did so again in a July 21 home game against the Boston Red Stockings.21 The only mention of Snyder using a mask in Louisville newspapers was a remark in the July 6 issue of the Courier-Journal. Snyder “bought himself a catcher’s mask in Boston,” wrote an unnamed correspondent, “but he hasn’t mustered up a sufficient amount of heart or cheek, whichever it may be, to introduce it to a Louisville audience yet.”22

This statement has been interpreted to mean that Snyder hadn’t yet worn it a regular-season match,23 but more likely it was a red herring. The Grays did not play a single home game between their only previous trip to Boston, when Snyder would’ve presumably purchased a mask from Wright Brothers, and the date of the newspaper’s remark.

In fact, Snyder had introduced his mask not to a hometown audience, but one in nearby Cincinnati. And unlike Hastings’ later experience when he first wore Thayer’s contraption in that city, Snyder’s play was unaffected by his mask.24 Nonetheless, there is no sign in surviving newspaper accounts that Snyder wore a mask again that season.

By the end of July, Louisville had overtaken the Boston Red Stockings to take the lead in the pennant race. Questionable play by several Grays during a string of late-August losses caught the attention of one Courier-Journal reporter who was extraordinarily well acquainted with the team: Haldeman. He shared his suspicions on the pages of the Courier-Journal, which helped uncover a game-fixing scheme known as the Louisville Scandal.25 On October 30, the directors of the Louisville Base Ball Club expelled four players, including the man Haldeman replaced in this game (Craver), two who played in it (Devlin and left fielder George Hall), and another who joined the Grays later (Al Nichols). Unable to go on, the franchise folded five months later.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Peter Morris for providing sources for information he used in Catcher regarding the first use of a mask, and Robert Tiemann for providing a contemporary newspaper account of Dorgan’s first use of a mask. This article was fact-checked by Laura H. Peebles and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted James Charlton, ed., The Baseball Chronology (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1991); Peter Morris’s A Game of Inches (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006) and Catcher (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009); Charles F. Faber’s SABR biography of Pop Snyder; and Woody Eckard’s “The 1877 National League’s Two Cincinnati Clubs,” published in SABR’s Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal. He also obtained pertinent material from 1877 Louisville Grays, St. Louis Brown Stockings, and Syracuse Star box scores published in the Louisville Courier-Journal, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Boston Globe, and New York Clipper; and from Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and statscrew.com.

Notes

1 “Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper, January 27, 1877: 346; “The College Champions for 1877,” New York Clipper, April 14, 1877: 18; “General Notes,” Evansville Journal, April 17, 1877: 8; James A. Tyng, “The First Baseball Mask,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette, July 17, 1895: 5.

2 “Answers to Correspondents,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 22, 1877: 2. The Wright Brothers store shared the same address as the Boston Base Ball Association headquarters. “Base Ball,” Boston Post, March 22, 1875: 3.

3 See, for example “Non-League Items,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1877: 7, and “Yesterday’s Games In and Around New York,” New York Sunday Mercury, June 3, 1877: 5.

4 “Beaten by the Bostons,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 29, 1877: 1; ”Base Ball,” Boston Globe, June 29, 1877: 5; “Bostons 9; Louisville 7,” Boston Journal, July 2, 1877: 3.

5 “The New Cincinnatis,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1877: 5.

6 Woody Eckard, “The 1877 National League’s Two Cincinnati Clubs: Were They In or Out and Why the Confusion,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2023, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-1877-national-leagues-two-cincinnati-clubs-were-they-in-or-out-and-why-the-confusion/.

7 For the balance of the regular season, NL owners remained undecided about whether the new Cincinnati franchise should be made a full member of the league and whether games played with the two Reds franchise games should or should not count toward the pennant. It would not be until December that league owners decided to extend league membership to the Cincinnati consortium, with “all of the games played by … the Cincinnati club … thrown out of the count.” “League Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 15, 1877: 298.

8 “The Game To-Day,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1877: 2; “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial, July 4, 1877: 3.

9 Cummings had replaced diminutive hurler Bobby Mathews, 3-12, with a 4.04 ERA over 15 of the original Reds’ first 17 games, with Hastings taking over for a pair of original Reds, regular catcher Nat Hicks and utilityman Henry Kessler. The new club also didn’t bring back second baseman Jimmy Hallinan or outfielder Ned Cuthbert. A week later, in summarizing player batting averages across the league, the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote that the Reds new management “got rid of its weak hitters.” “Base-ball,” Cincinnati Star, June 19, 1877: 1; “The New Club Ready for the Opening Game To-Morrow,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 2, 1877: 8; “The Cincinnati Red Stockings Step Down and Out,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 19, 1877: 2; “The League Batting Averages to Date,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 9, 1877: 8.

10 In 1882 the NL required that each team outfit its players in colors unique to the positions they played, with colors being standardized across the league. So, for instance, all first basemen wore red-and-white-striped shirts and caps. “1882 Color-coding System,” Threads of our game website, https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1882-color-coding-system/, accessed October 6, 2023.

11 “Fresh Notes and News,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1877: 2.

12 Two days later, Haldeman filled in at center field, not for his father’s team but for the shorthanded visiting Reds. The young journalist handed two chances in the field without error and singled to drive in the final run in a 3-1 Cincinnati victory. In the next day’s Courier-Journal, Haldeman (or one of his co-workers) joked, “The new $10,000 center-fielder of the Cincinnati Reds appeared with them for the first time yesterday. He possibly might command a better salary in some soup-house.” That game was later reclassified as an exhibition. “Good!” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 6, 1877: 4; “The Cincinnati Club,” New York Clipper, September 15, 1877: 197.

13 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1877: 2.

14 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Gazette, July 4, 1877: 4.

15 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Gazette.

16 The Cincinnati Commercial box score showed one Louisville runner thrown out at second.

17 See, for example, Peter Morris, Catcher (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 123, who called Dorgan the first major-league mask wearer, and James Charlton, ed., The Baseball Chronology (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1991), 32, which said he was “perhaps the first.” Morris told the author he tabbed Dorgan as the first major-league mask wearer based on The Baseball Chronology mention.

18 In his biography of Hotaling, late SABR author John F. Green describes the Stars catcher as having first worn a mask when returning from a one-month layoff after a foul tip injured an eye. The author identified a pair of games in mid-June during which Hotaling suffered eye injuries from foul tips; a June 11 contest with Tecumseh and a June 14 match with the St. Louis Brown Stockings. After the second injury, Hotaling was sidelined not for a month, but for eight days; out of the Stars lineup for games on June 15, 16, 18, and/or 19, he is shown in box scores catching in a June 23 rematch with the Brown Stockings. Multiple newspaper accounts of that game say nothing of Hotaling wearing a mask. Over the next 16 days, the Stars played seven games, with Hotaling playing right field in five of them and not at all in one other. No lineup information survives for a match Syracuse played against the Binghamton Crickets on June 29 in Syracuse, so it’s unknown where (or even if) Hotaling played that day. The earliest surviving contemporary mention of Hotaling wearing a mask appears in a newspaper account of a Stars match on July 10 in Pittsburgh vs. the Allegheny nine. In its account of that game, the Pittsburgh Commercial and Gazette describes how future Hall of Famer Pud Galvin stole home when Hotaling (his name misspelled Hoetling) “left the home base to get his wire mask.” John F. Green, Pete Hotaling SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/pete-hotaling/; “The Browns Defeated by the Syracuse Stars,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 15, 1877: 5; “The Stars Eclipsed,” Pittsburgh Commercial and Gazette, July 11, 1877: 4.

19 “A Lost Art,” St. Louis Times, August 9, 1877. For more details, see also Larry DeFillipo, “August 8, 1877: Brown Stockings’ Mike Dorgan becomes first major leaguer to adopt a catcher’s mask,” https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-8-1877-brown-stockings-mike-dorgan-becomes-first-major-leaguer-to-adopt-a-catchers-mask/.

20 “Notes, News and Miscellany,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 1877: 2.

21 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Gazette, July 14, 1877: 10; The remark in the Cincinnati Commercial was uncovered by protoball.org’s Richard Hershberger. Richard Hershberger, “Clipping: The Catcher’s Mask 3,” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/Clipping:The_catcher%27s_mask_3, accessed August 4, 2023; “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial, July 22, 1877: 4.

22 “General Notes,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 6, 1877: 4.

23 Morris, Catcher, 123.

24 In its coverage of Hastings’ first masked game, the Cincinnati Enquirer claimed that the backstop missed a foul bound because he was “blinded by the sun and his mask.” The Cincinnati Gazette snarked that either “Tyng’s mask” or nervousness “marred his usual fine play.” “The Cincinnatis Defeat the Famous Syracuse Stars,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 14, 1877: 8; “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Gazette, July 14, 1877.

25 Daniel Ginsburg, “The 1877 Louisville Grays Scandal,” Road Trips: SABR 1997 Convention Journal, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-1877-louisville-grays-scandal/.

Additional Stats

Louisville Grays 6

Cincinnati Reds 3

Avenue Grounds

Cincinnati, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.