September 8, 1897: A battery is born: Waddell, Schrecongost cross paths for first time in major-league debuts

As players warmed up for a National League game between the visiting Louisville Colonels and the first-place Baltimore Orioles at Union Park on September 8, 1897, a reporter from the Baltimore Sun approached Louisville player-manager Fred Clarke because he was unfamiliar with the Colonels’ battery. When pressed for details, Clarke seemed almost as confused as the reporter.

As players warmed up for a National League game between the visiting Louisville Colonels and the first-place Baltimore Orioles at Union Park on September 8, 1897, a reporter from the Baltimore Sun approached Louisville player-manager Fred Clarke because he was unfamiliar with the Colonels’ battery. When pressed for details, Clarke seemed almost as confused as the reporter.

“This man will pitch,” Clarke told him, pointing at the name “Weddel” on the scorecard, “and that tall fellow over there will catch. I don’t know what his name is.”1

Upon further inquiry, the reporter learned that “Weddel” was actually Waddell, as in left-hander Rube Waddell, and that the 5-foot-10 “tall fellow” had such a long last name that the player had to carefully spell it out a letter at a time: S-C-H-R-E-C-O-N-G-O-S-T, Osee Schrecongost.2 Neither new Colonel knew the other before their mutual big-league debut. “I don’t know,” Schrecongost replied to some fans who asked him about the starting pitcher. “I never saw him before.”

Added Waddell later when asked about his catcher: “Couldn’t tell you – first time I ever saw him.”3

The Orioles went on to a 5-1 win, staying percentage points ahead of Boston in the NL pennant race, but the Colonels’ new duo foreshadowed their successful futures. Waddell and Schrecongost held Baltimore’s high-powered, future Hall of Famer-fueled offense below its season average of 7.09 runs per game. The Baltimore Sun even criticized the Orioles, suggesting that five runs was “a very small score for three-time champions to make on a young player just making his entrance in the big league.”4

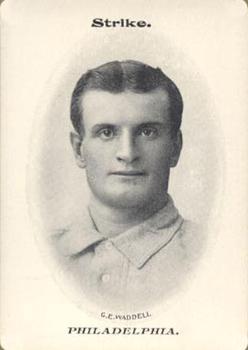

Waddell, a 20-year-old who grew up about 40 miles north of Pittsburgh in the small town of Prospect, Pennsylvania, had previously tried to sign with the Pirates. But even without formal minor-league experience, his reputation as a strikeout artist with amateur teams in Pennsylvania, such as Evans City and the Homestead Athletic Club, drew attention from other NL clubs and led to his signing with Louisville.

The Baltimore Sun described Waddell as “a big, tall left-handed young fellow, who looks a sort of second Cy Seymour.”5 Before a crowd of 1,053, the Orioles tested Waddell’s mettle immediately, though he did not appear intimidated by leadoff hitter Willie Keeler, who battled Clarke for the NL batting title.6 Keeler did not move his bat as Waddell threw three straight balls to open the game, but the rookie hurler bore down, pumped strikes across the plate, and Wee Willie flied out to left.

Baltimore’s Hughie Jennings and Joe Kelley followed with singles and ended up at second and third because Louisville rookie Honus Wagner,7 who had debuted in July, committed an error in center.8 After Jake Stenzel became Waddell’s first strikeout victim, Jack Doyle drove a two-run single to right to spot Orioles starter Jerry Nops a two-run lead.

Keeler collected his first of two hits in the game with two outs in the second. Jennings followed with a bounder that skipped past both shortstop Jack Stafford and Wagner in center, allowing Keeler to score. Jennings was stranded at third after Clarke tracked down Kelley’s deep fly to left, the first of two catches Clarke made against the Baltimore left fielder in a superb defensive showing. In the seventh, Clarke went back to the wall to put Kelley out. One play earlier, Clarke had dashed in from his position to make a shoestring catch of Keeler’s looper.

Wilbert Robinson drew a leadoff walk for the Orioles in the fourth, moved ahead on Nops’ sacrifice and Keeler’s single, and scored when Jennings poked a hit-and-run single to left. Keeler came home on Kelley’s fly to center,9 closing the scoring for Baltimore. Waddell finished the game with four scoreless innings.

In losing their fourth straight game, the Colonels scored their lone run in the fifth. Billy Clingman hit a one-out single, advanced two bases on an error, and scored when George Smith grounded to first.

Nops earned his 16th win while running Baltimore’s winning streak to five games. The Orioles won 3-2 the next day, and the third game went to Baltimore by forfeit after Louisville argued against several of umpire Kick Kelly’s decisions. As darkness began falling over the field, Clarke refused to continue the game after another close call went against his Colonels in the seventh inning. The Orioles led 6-5 at the time.10

With three weeks left in the season, Louisville sat 33 games out of first place after the series. The Colonels won only three of their final 14 games to finish 52-78 and 40 games off the pace. Only the dismal 29-102 record of the St. Louis Browns kept them from a fourth straight last-place finish.11 Baltimore improved to 80-33 after sweeping the Colonels, remaining a few percentage points ahead of Boston. The race went down to the last week of the season, when Boston won two of three games in Baltimore for an edge the Beaneaters never relinquished. The Orioles’ Keeler, McGraw, Kelley, and Jennings were eventually inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as was manager Ned Hanlon

The Colonels struggled to find consistent pitching in 1897, so when pitchers like Waddell and Doc Newton12 appeared as potential fixtures in the rotation, C.L. Moore, the team’s correspondent for The Sporting News, noted that “God knows they will be welcome.”13 A week later, Moore piled more praise on Waddell after he pitched well in an exhibition against the Indianapolis Indians, writing that he had the potential to become a future great because he has the “steam curves and noodle to be successful.”14

Waddell appeared in only one more regular-season game, a relief appearance on the back end of a home-field doubleheader against the Pirates on September 15. He allowed one run and struck out three over five innings while also leaving the crowd “splitting their sides with laughter by his ludicrous antics,” such as verbal cues and odd contortions of his body during his windup.15 Waddell also pitched in an exhibition against the Detroit Tigers of the Western League, the place he called home for the first part of the 1898 season. Sporting Life reported in late October 1897 that the Colonels were sending Waddell to Detroit as part of an agreement that also included Pat Dillard, John Richter, and Frank Shannon,16 though Waddell ended up back in Louisville in 1899 and earned seven wins in nine starts.

The 22-year-old Schrecongost – whose name was often shortened to “Schreck” in newspaper reports and box scores17 – was not retained on Louisville’s roster, even as the Louisville Courier-Journal correspondent suggested, “The weakest thing about Schrecongost is his name. He is a great ball player, and certainly made a fine showing as a backstop.”18

Among various minor-league stops throughout the year, Schrecongost had been catching for the Shamokin, Pennsylvania, club in the Central League late in the year.19 That team folded on September 7 due to a “lack of patronage,” and the Philadelphia Inquirer reported Schreck had major-league offers from Louisville and Philadelphia. How he got onto Louisville’s radar is unclear, but as one correspondent noted after Schreck went 0-for-3 in his debut: “Mr. Schutsenfest [sic] will have to go back to the mines.”20

“He caught well, but we have two catchers already who are just as good, if not better, and we did not need him,” said Colonels President Harry Pulliam. “If Louisville was in need of a catcher, it might be that we would buy him, but as it is, we have no place for him.”21

Schrecongost instead finished the season back in the Central Pennsylvania League, this time with Sunbury, and worked his way back to the major leagues with the Cleveland Spiders in 1898. Schreck and Waddell would cross paths again, first as opponents in the NL and in the minors and then as teammates in one of the game’s most beloved batteries with the Philadelphia Athletics in the earliest years of the American League.

Their manager there, Connie Mack, said, “Schreck was the Harpo Marx of his time. He was the fizz powder in the pinwheel that made Waddell great. He was colorful, unpredictable, eccentric, erratic, and filled with baseball genius.”22 Waddell and Schreck spent 1902 to ’07 together in Philadelphia, helping the Athletics win their first two AL pennants.

When apart, contemporaries noted, neither player seemed as comfortable on the field. That also seemed true away from the field, as the players became close friends and died within 100 days of each other in 1914, Waddell dying on April 1 and Schreck on July 9.

“Rube cannot pitch successfully to any other catcher. Schreck is a second-rater when catching any other pitcher,” Clark Griffith observed in 1904. “Hook them up together, and they are invincible. … It’s one of the anomalies of baseball how Schreck is perfection with Rube sailing them in, and yet nothing extra with any other man, and it’s comical to see Rube worrying along with any other backstop.”23

And it all began with a chance meeting in Baltimore.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Stew Thornley and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com,

Stathead.com, and Retrosheet.org websites. He also used information obtained from news coverage by The Sporting News, Sporting Life, the Baltimore Sun, and the Louisville Courier-Journal.

Notes

1 “Were Strangers to One Another,” Baltimore Sun, September 10, 1897: 6.

2 “Were Strangers to One Another.”

3 “Were Strangers to One Another.”

4 “Great Ball-Playing,” Baltimore Sun, September 9, 1897: 6.

5 “Great Ball-Playing,” Baltimore Sun, September 9, 1897: 6.

6 Clarke had kept pace with Keeler for several months of the season, but Keeler’s final .424 average easily outdistanced Clarke’s .390. Keeler won a second batting crown in 1898, hitting .385.

7 Like Waddell, Wagner grew up in Western Pennsylvania. His hometown of Chartiers is about six miles southwest of Pittsburgh.

8 Wagner, who is routinely cited as one of the best shortstops in major-league history, did not begin playing that position until 1901, when he appeared in 61 games as a shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He first played more than 100 games as a shortstop in 1903 and did so each year through 1915.

9 In 1894, the scoring rules changed, eliminating the sacrifice fly until 1908.

10 “Were We Robbed?” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 11, 1897: 3.

11 Louisville had finished 12th in 1894 (36-94), 1895 (35-96), and 1896 (38-93). The Browns, a precursor to the modern-day Cardinals, have never had a worse season than they had in 1897.

12 Despite Newton’s mention in The Sporting News, he did not appear in a game for Louisville in 1897.

13 C.L. Moore, “Next To Last,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1897: 1.

14 C.L. Moore, “Loyal Cranks,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1897: 1.

15 “Waddel Is Witty,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 16, 1897: 6.

16 John J. Saunders, “Louisville Lines,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1897: 4.

17 Newspapers used varying spellings of Schrecongost in box scores the day after his debut. The Baltimore Sun printed “Schr’ng’st,” the Louisville Courier-Journal printed “S’congost,” and the Philadelphia Inquirer printed “Sch’t.” Even some of the newspapers that tried to print his entire name had trouble: The Boston Globe printed “Schreicongost” and the New York Times printed “Schreicongast.” Pulliam was reportedly inundated with telegrams after the game from newspaper offices hoping to clarify the unusual name. “Schrecongost Not Signed,” Baltimore Sun, September 9, 1897: 6.

18 “Lost to Orioles,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 9, 1897: 6.

19 “Another Nice Game,” Sunbury (Pennsylvania) Evening Item, September 6, 1897: 1.

20 “Baseball Gossip,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Globe, September 10, 1897: 5.

21 “Schrecongost Not Signed.”

22 John R. Tunis, “An Atlantic Portrait: Cornelius McGillicuddy,” The Atlantic, August 1940: 214.

23 “Was a Bison Once,” Buffalo Times, January 28, 1904: 12.

Additional Stats

Baltimore Orioles 5

Louisville Colonels 1

Union Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.