Ken Singleton

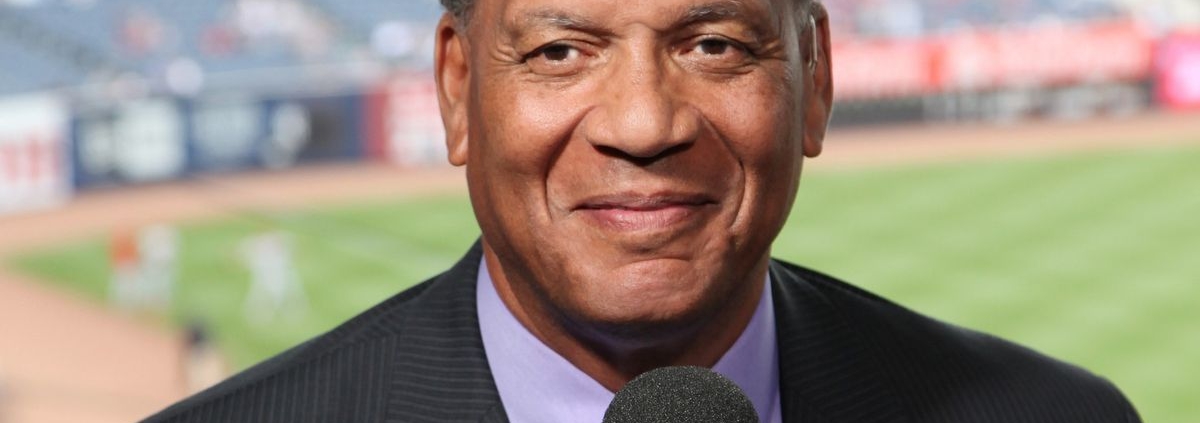

Patience and power made Ken Singleton one of baseball’s premier switch-hitters. After beginning his 15-year career (1970-1984) with the Mets and Expos, he was a three-time All-Star right fielder for the Orioles and the designated hitter for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions. After retiring, Singleton became a popular Yankees broadcaster.

Patience and power made Ken Singleton one of baseball’s premier switch-hitters. After beginning his 15-year career (1970-1984) with the Mets and Expos, he was a three-time All-Star right fielder for the Orioles and the designated hitter for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions. After retiring, Singleton became a popular Yankees broadcaster.

Kenneth Wayne Singleton was born on June 10, 1947, in New York City. His parents, Joe and Lucille (Hathaway) Singleton had another son, Fred, shortly before Ken turned five. Joe worked at the General Post Office Building near Madison Square Garden until he retired, and Lucille was an insurance underwriter. The family moved from East Harlem to Stamford, Connecticut, briefly when Ken was still small before returning to the Empire State. They settled in Mount Vernon, just north of the Bronx, in a home that had previously belonged to former Dodgers’ pitcher Ralph Branca’s family.1

Ken attended his first major league game at Ebbets Field when he was four.2 His father loved baseball. “My dad always had it on television,” he recalled. “That was around the time Jackie Robinson came in the league.” When Ken played his first baseball in the streets, against boys who were 12 or 13, he was a five-year-old left-handed hitter.3 “I saw all the other kids batting righty. I figured I was doing something wrong, so I changed.”4 During stickball marathons in Mount Vernon, he’d usually pretend to be the Giants against his friend Joey’s Dodgers. “We would go up and down the entire line-up, switching around to hit the way our favorite players batted.”5 “I always tried a little harder when I was Willie Mays.”6 In Little League, Ken batted right-handed like his hero.

“By the time I reached high school, I realized I might have a shot at pro baseball,” Singleton said. “Scouts had started to follow me around about that time and I was pretty big.”7 His 6-foot-4, 210-pound frame also caught the attention of Mount Vernon High School’s football coach, but Singleton’s father had overheard baseball scouts raving about his son that summer. “The football coach came over to the house, and my dad politely said, ‘He’s playing baseball,’” Singleton recalled.8

Singleton became a serious switch-hitter in the Federation League in the Bronx. “My coach, Charley Lane, saw me switching during practice. He suggested I try it in a game, and I went 4-for-5 that day with a home run and two doubles,” he explained.9 Singleton described his unusual combination of ambidextrous skills. “I throw right-handed, write left-handed, eat left-handed, shoot baskets left-handed, bowl right-handed.”10

No major league team drafted Singleton after his 1965 graduation, aware that he intended to attend college.11 He accepted a basketball scholarship from Hofstra University and averaged 18 points per game as a freshman.12 In the spring, he hit .327 for the Pride’s baseball squad.13 After he batted .425 in the Federation League that summer, however, Singleton decided to quit hoops.14 “College was a lot different than I thought it would be,” he explained. “I felt like they were paying me to play basketball. I figured, ‘Hey, if I’m going to get paid, why not make some real money and play baseball like I really want to do.’”15

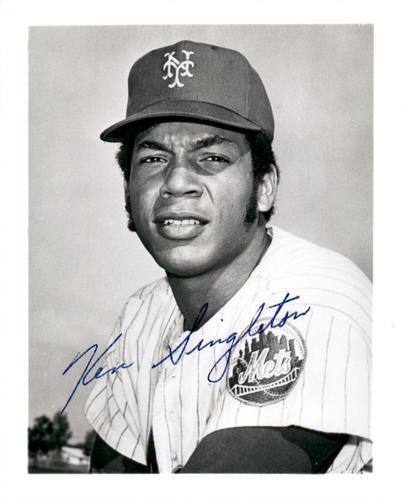

The Mets nabbed Singleton with the third pick of the January 1967 draft. His father and scout Bubber Jonnard watched as Mets president Bing Devine signed the 19-year-old to his first professional contract with a $7,500 bonus. “A switch-hitter, particularly in a boy his size, is a rarity,” remarked Devine. “He has a good, level swing both ways,” Jonnard observed. 16 With the Winter Haven (FL) Mets in 1967, Singleton’s 87 walks and .451 on-base percentage led the Single-A Florida State League. “I’ve got a pretty good idea where my strike zone is and I’m not about to go after bad balls,” he said.17 That fall, The Sporting News reported that Singleton “caught [Mets manager] Gil Hodges’ eye” in the Florida Instructional League.18

Singleton spent most of 1968 in Single-A. After 26 games with Raleigh-Durham of the Carolina League, he joined Visalia for 80 California League contests. Then, on August 4, he was promoted to the Triple-A International League and helped the Jacksonville (FL) Suns win the Governor’s Cup, emblematic of the winner of the International League playoffs. At his three stops, he drew a total of 109 walks and batted a combined .284 with 16 homers. “The unusual thing about him is he’s a high ball hitter both ways,” noted Suns’ skipper Clyde McCullough.19 The Mets added Singleton to their 40-man roster.

Playing at Double-A Memphis in 1969, Singleton broke his thumb on May 20.20 He returned to finish with a .309 average and homered in the division clincher as the Memphis Blues won the Texas League East pennant.21 In the playoff, Memphis went on to defeat Amarillo for the Texas League championship. In addition to earning All-Star honors in the circuit, he was voted a Topps’ year-end Class AA West All-Star.22

Singleton’s performance for the Triple-A Tidewater (VA) Tides propelled him into the majors in 1970. When the Mets visited for an exhibition on June 1, he homered in a four-hit display.23 On his 23rd birthday nine days later, he went deep twice in Buffalo.24 Entering the final week of June, Singleton led the International League in batting (.388), homers (17), and on-base percentage (.513). “He is both selective and aggressive,” remarked Tides’ skipper Chuck Hiller.25 After a loss in Columbus on June 23, Hiller told the budding star that the Mets wanted him in uniform the following day at Wrigley Field. “I was kind of stunned,” Singleton recalled.26 Batting third and playing left field, he went 0-for-4 in his debut.

Two nights later in Montreal, Singleton notched his first hit, an RBI single to center off Steve Renko. Before that game was over, he took Bill Stoneman deep. The rookie’s five homers before the end of July included a bomb at Candlestick Park described as “maybe the longest ball ever hit here” by the Giants’ publicist.27 Singleton credited Donn Clendenon, the Mets’ 6-foot-4 first-baseman who’d loaned him a suit jacket when he arrived from Triple-A. “Clendenon told me that with my long arms I could stand back from the plate and I’d still be able to hit the outside pitch,” he said. “He also told me not to be ashamed to go to the opposite field.”28 After pulling a hamstring and trying to return prematurely, however, Singleton didn’t homer in the final two months and finished the year batting .263.29

Two nights later in Montreal, Singleton notched his first hit, an RBI single to center off Steve Renko. Before that game was over, he took Bill Stoneman deep. The rookie’s five homers before the end of July included a bomb at Candlestick Park described as “maybe the longest ball ever hit here” by the Giants’ publicist.27 Singleton credited Donn Clendenon, the Mets’ 6-foot-4 first-baseman who’d loaned him a suit jacket when he arrived from Triple-A. “Clendenon told me that with my long arms I could stand back from the plate and I’d still be able to hit the outside pitch,” he said. “He also told me not to be ashamed to go to the opposite field.”28 After pulling a hamstring and trying to return prematurely, however, Singleton didn’t homer in the final two months and finished the year batting .263.29

That winter, he was a Puerto Rican League All-Star for manager Roberto Clemente’s San Juan Senators.30 Clemente also played a few games. “I never saw a guy so dedicated to playing ball,” Singleton said.31 “He told me if you want to hit .300, set your sights on .325. If you want to drive in 100 runs, go for 125. Then, if you fall a little short and hit .304 and drive in 100, nobody will be disappointed.”32 The Mets were disappointed, however, with the .245 batting average and 13 homers that Singleton produced in 1971. Hall of Fame slugger Ralph Kiner tutored him in the Florida Instructional League. “I was to eliminate one problem,” Kiner explained. “[Singleton] would drop his hands and push out at the ball.”33 Singleton, who considered himself more of a line-drive hitter, said, “They wanted me to hit 40 homers.”34

He never hit another one for the Mets. Three days after Hodges’s shocking death from a heart attack in spring training 1972, Singleton, Mike Jorgensen and Tim Foli were traded to the Expos for Rusty Staub. “The one we really hated to lose was Jorgy,” said Mets GM Bob Scheffing.35 “It hurt emotionally when I was traded to Montreal,” Singleton confessed. “But then I realized I would be playing every day.”36

He was Montreal’s Opening Day left fielder but faded after a strong start. Sent home early from a June road trip, he said, “I was miserable, sick and with welts all over my body.”37 His batting average was a sickly .219 when doctors finally determined that his allergies weren’t caused by chocolate ice cream or seafood as they’d suspected but, rather, the Expos’ wool uniforms! After returning to the lineup in a custom double-knit on July 5, Singleton batted .310 the rest of the way. Foli, his road roommate, removed wool blankets from their hotel rooms. They’d first shared accommodations in the minors and, in 1971, Singleton and Foli were “believed to be the first integrated rooming in Mets history.”38

Guided by hitting coach Larry Doby, Singleton bloomed into a star in 1973. “Doby worked with me every day and he convinced me that I could hit for a high average besides hitting with power,” he explained.39 “He got me thinking about what the pitcher’s going to do.”40 Singleton played all 162 games and batted .302 with 23 homers, including one from each side of the plate on July 1 in a doubleheader at Pittsburgh. His totals of 100 runs scored and 103 RBIs broke Staub’s franchise records and lasted until 1982. His .425 on-base percentage led the majors, and his total of 123 walks was never surpassed in Expos history.41 “I’m just doing what I’m capable of doing,” he insisted. “This isn’t a great year.”42

Initially, it looked like 1974 might be. In January, Singleton married Colette Saint-Jacques, a Quebec native he’d met at the Montreal Forum.43 The couple bought a home in Quebec. He was batting over .300 when he appeared on the cover of The Sporting News in late May, but slumped through a .240 second half. “I sprained my wrist sliding last July, and it affected my hitting,” he disclosed that fall.44 His home run total declined sharply to nine, and he committed a career-worst 11 errors.

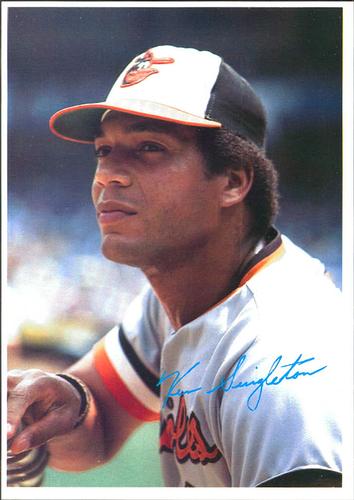

On December 4, the Expos dealt Singleton and pitcher Mike Torrez to the Orioles for southpaw Dave McNally, outfielder Rich Coggins and a minor leaguer. “I really wasn’t surprised Montreal traded me,” Singleton said. “They needed left-handed pitching and they just didn’t have that many guys of value to put in a deal.”45 From Baltimore’s perspective, the move was a response to the rival Yankees’ acquisition of Bobby Bonds. “We wanted Bonds and the fact that we didn’t get him made us realize we had to get someone else awfully quick,” explained assistant GM Jim Russo.46

Orioles manager Earl Weaver asked Singleton to lead off in 1975, but the outfielder thought he was too slow. “My brother Freddie’s got all the speed,” he said.47 (As a hurdler, Fred Singleton had co-captained Penn State’s 1974 IC4A champions.48 The brothers’ talented family included an uncle, Harvey Singleton, who’d played football for the 1952 Toronto Argonauts, and a cousin, Doc Rivers, who became a 1983 second-round NBA draft pick.) After Weaver explained that he simply wanted Singleton to get on base, Singleton drew 118 walks and reached safely 295 times. Both figures remain Baltimore records as of 2021. He also stroked a career-high 37 doubles and bunted for a single in his final game to finish with a .300 average. “Kenny hits .300 without getting three infield hits a year,” remarked Baltimore coach Jim Frey.49 Singleton was voted Most Valuable Oriole by the team’s writers and announcers.50

Meanwhile, the Expos lost McNally to retirement in June and sold Coggins to the Yankees while Torrez won 20 games for the Orioles. “Mike and I knew it would be a lopsided deal when it was made,” Singleton said.51 Charles Bronfman, chairman of Montreal’s board of directors, confessed, “I think Singleton was the type of guy that …we really shouldn’t have traded. He had a lot of charisma. He was a good guy, he married a local girl, he was a good contributor to the club.”52

In 1976, Ken played the bulk of his games in left field for the last time, accommodating right fielder Reggie Jackson, whom Baltimore had traded for in spring training. Singleton also moved down in the batting order, usually hitting fifth. When he walloped the only walk-off homer of his career on May 22 –a two-out grand slam off Detroit’s Jim Crawford— it was his first AL home run with anyone on base. When Singleton struggled to hit his weight by the beginning of June, he recalled checking the newspaper’s batting statistics with his father as a kid to discern the league’s “strongest” hitter –the one at the bottom holding everybody else up. “I never quite pictured myself in that spot,” he said.53 He rebounded to hit .312 after June 2 but Baltimore finished a distant second to the Yankees.

Singleton’s family grew in November with the arrival of his son, Matthew. The Orioles, on the other hand, lost Jackson, Bobby Grich and Wayne Garland in the first winter of free agency. Singleton could have tested the market, but during spring training he signed a five-year contract to remain with Baltimore. “Of the three organizations I’ve been connected with, this is by far the best,” he said.54

Singleton’s .328 batting average and .438 on-base percentage in 1977 established personal bests and Orioles’ single-season records.55 (Melvin Mora hit .340 for Baltimore in 2004 but Singleton’s on-base mark still stood as of 2021. Although Bob Nieman had a .442 on-base percentage in 1956, he did so in only 478 plate appearances, having begun the season with the White Sox). On July 19 at Yankee Stadium, Singleton played in his first All-Star Game. One week later in the same ballpark, he became the first player to homer into the center field bleachers. No other visiting player would do it for a decade.56 The blast came in the early stages of a streak in which Singleton reached base via a hit or a walk in 49 consecutive games. “He’s got to be the best I’ve ever seen when it comes to taking two strikes, waiting for something he can hit. And even then, he can fight off the tough pitches,” raved Weaver.57 “I’m not trying to put him in the superstar category, but when it comes to consistency, Singleton ranks right up there with Brooks [Robinson and Frank [Robinson.”58 Singleton finished third in AL MVP voting. That winter, his family moved to California and he underwent surgery to correct an elbow injury stemming from his amateur pitching days. For two years, he’d felt like every throw he made might be his last. “Sometimes the last two fingers on the arm would be numb,” he said.59 The injury made it even more remarkable that Singleton had batted over .400 right-handed until the final weeks of 1977.60 Throughout his career, he was significantly stronger as a lefty for both average (.291 to .260) and slugging (.453 to .391).

Though Singleton batted a career-high .318 as a lefty and enjoyed a personal-best 17-game hitting streak in 1978, his slow recovery from surgery limited him to a .229 right-handed mark and a single outfield assist. To regain his strength that winter, he rode a bike with his two-year-old on his back and frequently visited neighbor Rick Dempsey’s backyard batting cage.61

Singleton quickly proved he was again healthy in 1979. Ten days after his second son, Justin, was born during the season-opening home stand, he launched eight round-trippers in 13 games, prompting teammates to call him “Homerton.”62 During a season of ‘Orioles Magic’ in which Baltimore romped to the AL East Title with a 102-57 record, “Come on Ken, put it in the bullpen” was one of superfan ‘Wild Bill’ Hagy’s signature cheers. Singleton launched a career-high 35 homers, a single-season total bested only by Mickey Mantle among switch-hitters at the time.63 Singleton’s 111 RBIs, 304 total bases and .533 slugging percentage were also career bests.

In the playoffs, Singleton batted .364 but he couldn’t corral the decisive home run hit by Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell in Game Seven of the World Series that sealed the Orioles’ fate. That fall, he toured Japan with an All-Star squad. On the flight home, he sat next to his chief competition for AL MVP honors, the Angels’ Don Baylor. “Singleton asked me why I had to pick this year to have my best season ever,” Baylor recalled.64 When the results were announced, Singleton received three first-place votes but finished second to his former teammate.

The Singletons sold their California home and moved to Timonium, Maryland. In January, Ken signed a three-year contract extension to remain with Baltimore through 1984. “I really never thought seriously about becoming a free agent,” he said. “It’s really great to be a ballplayer here. The fans are Orioles crazy.”65

After postponing recommended knee surgery, he started slowly in 1980, batting .236 through June 11 as the Orioles struggled with a losing record.66 By season’s end, however, his BA was .304 and Baltimore won 100 games to finish second behind the 103-59 Yankees. Singleton’s 19 game-winning RBIs topped the AL67 With 104 RBIs overall, he and Eddie Murray (116) became the American League’s first pair of switch-hitting teammates to reach the century mark in the same season.68

Singleton homered in his first plate appearance of 1981 and delivered an Orioles’ record 10 consecutive hits — six for extra bases — two weeks later.69 His .472 April average earned him Player of the Month honors and he led the league in hitting as late as June 8. Before each at bat, he picked up three pebbles to remind him that the pitcher had to throw three pitches over the plate. His vision was better than 20-20. “A lot of guys go by the spin of the ball, but I go by speed,” he explained.70 “Patience, discipline and knowing your own limitations, those are the real key.”71

“Ken Singleton is the most intelligent hitter I’ve ever seen in baseball,” Weaver insisted. “He knows how to work the pitcher into giving him the pitch he wants.”72 Pitching coach Ray Miller described sitting next to Singleton in the dugout. “He’ll go hitter by hitter with me and tell me what the guy will throw on each pitch. It’s amazing how often he’s right.”73

The day after Singleton’s 34th birthday, major league players went on strike for nearly two months. “You would keep working out, thinking the season was about to resume,” he recalled. “But when nothing happened, I got busy doing other things.”74 He worked at Baltimore’s WBAL-TV, where he’d interned the previous winter. When baseball returned with the All-Star Game in Cleveland, Singleton started for the American League and collected two hits, including a homer off Cincinnati’s Tom Seaver. He fizzled toward the finish, however, batting .154 without a home run in Baltimore’s final 35 games. “I really didn’t do anything during the strike,” he acknowledged later. “I just didn’t realize that the inactivity was sapping my strength.”75

In 1982, Singleton reported to spring training 15 pounds lighter after arthroscopic knee surgery, aware that he might be Baltimore’s designated hitter more frequently following the off-season acquisition of outfielder Dan Ford.76 But Singleton was disappointed to discover that he’d be a full-time DH. “Just being the DH makes the game seem awfully long,” he observed. “You have to try to keep your mind occupied, so you don’t think of the previous at bat.”77 He hit .251, including a futile .177 right-handed without a single home run. He was baffled until a series of mid-season strength tests revealed that his right arm had become 18% weaker than his left. “It was actually a relief for me to find out something was wrong physically,” he said.78

Most of Singleton’s good news that season came off the field. His parents had retired and moved near him. Major League Baseball presented him with the Roberto Clemente Award, given annually to the player who best exemplifies sportsmanship, community involvement and on-field contributions. For buying blocks of Orioles tickets for senior citizens and working on behalf of Sickle Cell Services and United Cerebral Palsy, Singleton received Baltimore’s Jimmie Swartz Medallion.79

After rebuilding his right-arm strength, Singleton joined a new-look Orioles squad in 1983.80 Weaver had retired, and new manager Joe Altobelli moved Cal Ripken into the third spot in the batting order Singleton had occupied since late 1978 in front of Murray. Baltimore won another pennant with Ripken and Murray finishing first and second in MVP voting, but a resurgent Singleton led the club in on-base percentage and slugging as late as July 11. He ranked third on the club in RBIs during his comeback season and his 99 walks were the AL’s second-highest total, the 12th straight year in which he finished in his league’s top 10. In Baltimore’s four-game ALCS victory over the White Sox, Singleton doubled twice, but the DH was not permitted in the 1983 World Series. He struck out in his only official at bat against the Phillies, but when the Orioles seized control of the series with a come-from-behind victory in Game Four, Singleton drew a four-pitch, bases-loaded walk from Cy Young Award winner John Denny to force home the tying run. He was one of a World Series-record eight pinch hitters deployed that night, the second of four straight the Orioles used in the sixth inning.81

In 1984, Singleton was already slumping when a severely bruised right instep sent him to the disabled list in May.82 He homered against the Tigers on his 37th birthday after returning, and collected his 2,000th hit 15 days later, but entered the All-Star break with only 14 RBIs and became a part-time player. “I still enjoy playing, but I don’t want to continue as a mediocre player,” he said.83 “The thing I’m proudest of is, with the exception of the strike year, the lowest number of wins we’ve had since I’ve been here is 88.” 84 Baltimore slipped to 85 victories in 1984, however. Despite swatting two grand slams in September, Singleton’s .215 batting average and six homers were not enough to convince the Orioles to pick up the option on his contract. He accompanied the club on a post-season tour of Japan, still hopeful that another AL club would sign him to DH. His agent contacted the Toronto Blue Jays to gauge their interest.85

Singleton did work in Canada in 1985, but as an announcer for Blue Jays and Expos games on The Sports Network. After 15 major league seasons, his career ended with a .282 batting average and 1,065 RBIs in 2,082 games. At the time of his retirement, only 19 players in history had exceeded his total of 1,263 walks and only two switch-hitters had hit more than his 246 home runs.86 In 1986, he was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame. He was a weekend sports anchor for Baltimore’s WJZ-TV through 1988 and continued to broadcast Expos games into the 1990s. After divorcing, he married Suzanne Molino in 1991 and fathered two more children, son Dante and daughter Jellica. His son Justin played minor league ball in the Blue Jays organization, peaking in Triple-A.

Singleton did work in Canada in 1985, but as an announcer for Blue Jays and Expos games on The Sports Network. After 15 major league seasons, his career ended with a .282 batting average and 1,065 RBIs in 2,082 games. At the time of his retirement, only 19 players in history had exceeded his total of 1,263 walks and only two switch-hitters had hit more than his 246 home runs.86 In 1986, he was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame. He was a weekend sports anchor for Baltimore’s WJZ-TV through 1988 and continued to broadcast Expos games into the 1990s. After divorcing, he married Suzanne Molino in 1991 and fathered two more children, son Dante and daughter Jellica. His son Justin played minor league ball in the Blue Jays organization, peaking in Triple-A.

Singleton began a long run as a New York Yankees broadcaster in 1997. In spring training 2018, at the beginning of his 22nd season with the YES Network, the 70-year-old Singleton announced that he would retire at the end of the year. “I was able to call World Series games and All-Star Games for Major League Baseball International, who telecast games to over 200 countries to help spread baseball throughout the world. In that regard, I thought I was somewhat of an ambassador for the game,” he said.87 Before the summer of 2018 was complete, however, supportive pleas from fans and colleagues convinced Singleton to postpone his full retirement. He continued to announce a reduced number of Yankees games for YES until finally retiring at the end of the 2021 season.

Last revised: February 18, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Ken Singleton, 1972 Topps Baseball Card.

2 Michael O’Keefe and Bernie Augustine, “Kenny’s Singular Father,” New York Daily News, June 16, 2013: 65.

3 Bill Rhoden, “Playing for Pay: Fantasy Realized Isn’t as Much Fun,” Baltimore Sun, June 12, 1979: B1.

4 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” Daily News (New York, New York), June 28, 1970: 247

5 Sam Goldpaper, “Fred Doubles Singleton Name,” New York Times, August 16, 1970: 151.

6 Joe Donnelly, “College Dropout a New Met Drop-In,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), March 15, 1969: 23.

7 Rhoden, “Playing for Pay: Fantasy Realized Isn’t as Much Fun.”

8 O’Keefe and Augustine, “Kenny’s Singular Father.”

9 Ian MacDonald, “Swift Swat Pace Finds Singleton Striving to Improve,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1973: 32.

10 “Major Flashes,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1971: 33.

11 Jack Lang, “Huge Singleton Plays Big Role as Met Muscle Man,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1970: 10.

12 1980 Baltimore Oriole Media Guide: 150.

13 Steve Jacobson, “Met Farm a Rugged Start — Or the End,” Newsday, March 21, 1967: 25A.

14 Barney Kremenko, “19-Year-Old Switch-Hitter Signs as No. 1 Draft Pick,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1967: 13

15 Rhoden, “Playing for Pay: Fantasy Realized Isn’t as Much Fun.”

16 Kremenko, “19-Year-Old Switch-Hitter Signs as No. 1 Draft Pick.”

17 Dave Lewis, “Strike Zone is Quite Familiar to Tide Slugger Ken Singleton,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1970: 35.

18 “Mets Musings,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1967: 41.

19 Young, “Young Ideas.”

20 “Engbers Joins Blues,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1969: 39.

21 “Memphis, Amarillo Grab TL Pennants,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1969: 40.

22 “Writers Name Minors’ Double-A, A All-Stars,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1970, 47.

23 Lewis, “Strike Zone is Quite Familiar to Tide Slugger Ken Singleton.”

24 “Int Index,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1970: 41.

25 Lewis, “Strike Zone is Quite Familiar to Tide Slugger Ken Singleton.”

26 “Ken Singleton Reminisces About His Call to the Majors,” Hartford Courant, July 11, 1970: 21.

27 Jack Lang, “Huge Singleton Plays Big Role as Met Muscle Man,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1970: 10.

28 “Ken Singleton Reminisces About His Call to the Majors.”

29 Jack Lang, “Met Musings,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1970: 5.

30 “Puerto Rican Pacers,” The Sporting News, February 6, 1971: 47.

31 Bob Dunn, “Singleton, Staub Throw-In, Eclipsing Rusty,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1974: 3.

32 Ken Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1981: 2.

33 Dunn, “Singleton, Staub Throw-In, Eclipsing Rusty.”

34 Buck Harvey, “Singleton Provides Drive for Orioles,” Newsday, July 5, 1975: 26.

35 Jack Lang, “Slugger Staub Gives Elated Mets a Pat Lineup,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1972: 5.

36 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

37 Ian MacDonald, “Expos Expand Smiles in Sizing Up ‘The Trade’,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1972: 7.

38 “Met Musing,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1971: 10.

39 Ken Nigro, “Singleton Eyes a Big Season,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1981: 33.

40 Dunn, “Singleton, Staub Throw-In, Eclipsing Rusty.”

41 After the Expos became the Washington Nationals, Bryce Harper walked 124 times in 2015 to break Singleton’s base-on-balls record. As of 2020, Harper’s 130 walks in 2018 are the franchise record.

42 MacDonald, “Swift Swat Pace Finds Singleton Striving to Improve.”

43 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 155.

44 Doug Brown, “Orioles Crowing Over Clout Supplied by May, Singleton,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1974: 47.

45 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”.

46 “Orioles Get Singleton but Give Up McNally,” Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1974: 11.

47 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

48 “J Fred Singleton,” https://www.amazon.com/J-Fred-Singleton/e/B01L4KP1I0 (last accessed December 15, 2020).

49 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

50 1976 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 83.

51 Jim Henneman, “Orioles Chirp in Double Time Over Mike and Ken,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1975: 9.

52 Bob Dunn, “Expos’ Boss Bronfman Admits Deal Backfired,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975: 15.

53 Jim Henneman, “Singleton’s Once-Dead Bad Now Buries Rivals,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1976: 7.

54 Jim Henneman, “Five-Year Oriole Contract to End Singleton’s Worries,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1977: 35.

55 This refers to Baltimore Orioles records since 1954, not statistics compiled when the franchise was previously known as the St. Louis Browns. In 1956, Bob Nieman posted a .442 on-base percentage in 478 plate appearances for the Orioles, but he started the season with the White Sox and had an overall figure of .436 in 522 American League PA’s.

56 Reggie Jackson did it in the 1977 World Series and the 1981 regular season, but no visiting player would achieve the feat until Boston’s Mike Greenwell in 1987. Jack O’Connell, “New York Yankees,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1994: 31.

57 Jim Henneman, “Murray No Picture Hitter, But He’s in Orioles’ Album,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1977: 41.

58 Jim Henneman, “Loss of Singleton Doubles Troubles of Orioles,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1977: 20.

59 Jim Henneman, “Singleton Confesses He Had Sore Arm in ’77,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1978: 62.

60 1978 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 113.

61 Thomas Boswell, “Singleton on the Verge of a Noisier Excellence,” Washington Post, May 10, 1979: F3.

62 Ken Nigro, “Orioles Turn from Doves to Dinosaurs at Bat,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1979: 17.

63 Ken Singleton, 1982 Topps All-Star Baseball card.

64 “Angels Notes,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1979: 58

65 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

66 Ken Nigro, “Orioles Threaten Runaway for Aches and Pains Title,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1980: 39.

67 Ken Singleton, 1981 Donruss Baseball Card.

68 In the NL, Reggie Smith and Ted Simmons previously did it for the 1974 Cardinals. 1981 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 155.

691982 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 147.

70 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

71 Nigro, “Singleton Eyes a Big Season.”

72 Nigro, “Baltimore’s Singleton is Mr. Consistency at the Plate.”

73 Nigro, “Singleton Eyes a Big Season.”

74 Ken Nigro, “Orioles: Singleton Stopped,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1981: 32.

75 Jim Henneman, “Singleton Builds Strength in Arm” The Sporting News, February 7, 1983: 38.

76 Peter Gammons, “Beware Quickie Studies of Pitcher Pacts,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1982: 37.

77 Ken Nigro, “New Job Challenging to DH Singleton,” he Sporting News, May 31, 1982: 26.

78 Jim Henneman, “Singleton Regains Right Arm Strength,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1983: 36.

79 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 155.

80 Jim Henneman, “Tempy or Parrish Could Fill O’s Gap,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1982: 26.

81 “Pinch-Hitters Set Record,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1983: 58.

82 Jim Henneman, “Murray is Moving Beyond Greatness,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1984: 21.

83 Jim Henneman, “Singleton’s Goal: Catching the Tigers,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1984: 15.

84 Henneman, “Singleton’s Goal: Catching the Tigers.”

85 Marty York, “Ken Singleton Looks to Jays,” December 18, 1984: S1.

86 1985 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 84.

87 Bill Ladson, “Q&A: Singleton Enters Final Season in Booth,” https://www.mlb.com/news/ken-singleton-retiring-from-mlb-broadcasting-c268547520 (last accessed December 16, 2020).

Full Name

Kenneth Wayne Singleton

Born

June 10, 1947 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.