Cal Ripken

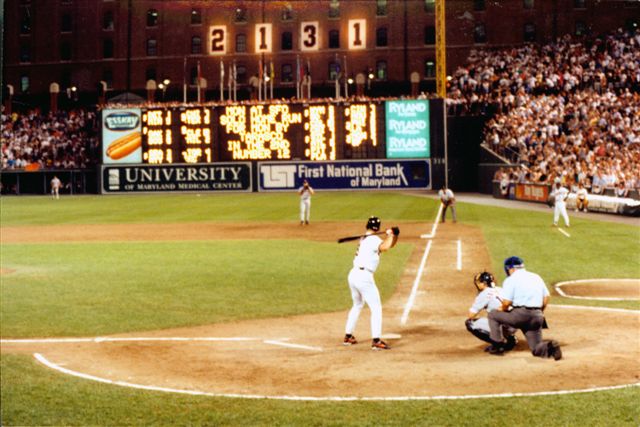

On a warm September evening in 1995 at Baltimore’s Camden Yards, Oriole shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. helped restore America’s faith in baseball. The contentious nature of the previous year’s strike had left many of the sport’s dedicated fans wondering what the future held for their beloved national pastime.

Following the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, the great Babe Ruth inspired disillusioned fans with his towering home runs and larger than life persona. Years later, Cal Ripken’s unparalleled work ethic and outstanding play on the diamond gave alienated fans of another generation a reason to come back to the game.

Calvin Edwin “Cal” Ripken was born on August 24, 1960, in Havre De Grace, Maryland and was raised in nearby Aberdeen. He was the second child and first son of Violet “Vi” and Calvin Edwin “Cal” Ripken Sr.

Ripken Sr. was a former professional baseball player who started his career as a highly touted catcher in the Baltimore farm system. After suffering a career-ending shoulder injury, he went on to manage a number of the Orioles’ minor league affiliates, eventually working his way up to Baltimore where he coached and later managed the Orioles.

The senior Ripken was an astute baseball man who willingly shared his knowledge of the game with hundreds of players who came through the Oriole farm system. In addition, his children were taught every nuance of the sport from a man who epitomized what is known in Baltimore as the Oriole Way. Hard work, implementing fundamentals and promoting from within the organization are some of the foundations of this time-honored tradition.

As a boy, Cal was always at the ballpark with his dad. During that time he hung out with the players, soaking up tips and baseball advice. Once, while playing catch with Doug DeCinces during pre-game warm-ups at Asheville, North Carolina, a disturbed individual began shooting up the field with a rifle. DeCinces grabbed the startled youngster and carried him into the dugout amidst a hail of gunfire. In addition to this life saving effort, Ripken credits DeCinces as being one of his most influential baseball mentors.

When Cal Sr. joined the Baltimore Oriole coaching staff, Junior became a regular at Memorial Stadium. Young Cal practiced with the players, asking them their opinion about various on-field strategies and plays while absorbing everything he could about the game.

Cal Jr. was an honor roll student at Aberdeen High and a standout performer on the school’s soccer and baseball teams. His athletic prowess combined with his outstanding grades made him a viable candidate for a college scholarship. Cal knew from an early age that he wanted to pursue a professional baseball career, a fact he made known to the college scouts who regularly attended his high school games. However, a few schools still contacted his family, among them the United States Military Academy at West Point, which expressed interest in him as a soccer player.

Junior pitched and played shortstop for Aberdeen High. He led the school to the Maryland State Championship during his senior year. Cal hit .496 that season while posting a 7–2 record on the mound to go along with a miniscule 0.79 earned run average.1 Junior tossed a two-hitter and struck out seventeen batters in the District V Class A Final against Arundel.

Orioles’ director of scouting Tom Giordano thought Ripken had the potential to be a solid major league pitcher. However, scout Dick Bowie believed Cal had the talent and ability to be an everyday player. Ripken Sr. was also in favor on his son starting out his professional career as an infielder, telling him he could always switch back to pitching if things didn’t work out.

Cal Ripken Jr. was selected by the Orioles in the second round of the 1978 Amateur Draft. The Boston Red Sox were originally slated to have this pick, but they relinquished it by selecting pitcher Dick Drago in the re-entry draft. Ripken was the fourth player picked by Baltimore that year.

Other major league teams were looking at Cal as a pitcher, but the Oriole front office kept an open mind as to what position he would play. When asked by a reporter about Ripken’s role in the organization, Giordano replied, “We’re still not sure where Cal Ripken will fit in for us. We’re going to wait and see before saying anything definite.

In the summer of 1978, Ripken signed a minor league contract with Baltimore. He received a $20,000 signing bonus and was sent to the Bluefield Orioles of the Appalachian State League. Bluefield’s rookie manager Junior Miner needed an infielder, so despite his pitching credentials, Cal began his professional career at shortstop. Initially, he was slated to back up highly regarded prospect Bob Bonner. A short time later, Bonner was promoted to Double A ball and Cal became the starter. He started off a bit slowly at the plate but finished the season with a respectable .264 average. Surprisingly, he did not hit any home runs that year. In the field, Ripken struggled a bit with his throws but otherwise played well.

After a few more years of minor league seasoning and a couple of winters playing against major league competition in Puerto Rico, Cal finally got his shot at the big leagues.2

Ripken went to spring training with the Orioles in 1981 but was eventually farmed out to the Rochester Red Wings, Baltimore’s Triple A affiliate. He went on to have a fine year, hitting .288 while torching International League pitchers for 23 home runs and 75 RBIs in 114 games before being called up to the Orioles in early August.

Ripken went to spring training with the Orioles in 1981 but was eventually farmed out to the Rochester Red Wings, Baltimore’s Triple A affiliate. He went on to have a fine year, hitting .288 while torching International League pitchers for 23 home runs and 75 RBIs in 114 games before being called up to the Orioles in early August.

During his stay with the Red Wings, Cal played in the longest game in the history of professional baseball. On April 18, Rochester squared off against the Pawtucket Red Sox on a windy cold day at the latter’s home field. The teams fought to a 2-2 tie over 32 innings before the umpires called a halt after four the next morning. Pawtucket eventually won the marathon contest 3-2 in the 33rd inning when the teams met again on June 23. The battle played out over three days, consuming eight hours and 25 minutes. Future Hall of Famer Wade Boggs went 4-for-12 for the Sox, including a game-tying RBI double in the bottom of the 21st inning. Ripken played the entire game at third base for the Red Wings, going 2-for-13.

The major leagues were in the midst of playing a split schedule in 1981 due to a midseason strike. Cal did not see much action as he served as an understudy to third baseman Doug DeCinces. The Orioles were contending for a second half playoff spot, and Birds manager Earl Weaver went with his veteran players down the stretch. Ripken made his first major league appearance as a pinch runner on August 10 and a few days later made his defensive debut as a late-inning substitute for shortstop Lenn Sakata. Oriole shortstop Mark Belanger, who was playing his last year with the club, gave Junior many valuable tips on playing the infield that season.

The following year, Doug DeCinces was traded to California, and Cal was given a chance to win the starting job at third base. Ripken started off the 1982 campaign with three hits including a home run. After that, he began to struggle, at one point going 1-for-21, but Oriole manager Earl Weaver never lost confidence in the future Hall of Famer.

Fighting his way through the slow start, Cal eventually found his stroke, hitting safely in 13 out of 14 games. By early June, his batting average was up to .250. He was in the starting lineup on May 30 and played every game for the rest of the year. This date would have significant meaning in years to come. The next day, Cal swiped home against the Texas Rangers on the front end of a double steal for his first major league stolen base. On July 1, Oriole manager Earl Weaver started Ripken at shortstop for the first time. The Birds’ skipper told the young infielder to concentrate on making the routine play and everything else would fall into place. When asked about the move Weaver replied, “It has always been easier to find a third baseman that could hit the ball out of the park than a shortstop who can. You never know, Rip might be a great shortstop. He’s played the position before.”

Because of Ripken’s size (6-feet-4 and about 225 pounds), a number of people in the Baltimore front office opposed the move. Years later, when asked about playing Ripken at shortstop, Weaver remarked, “I was an organization man. Been with Baltimore my whole career. Did what they said and didn’t mind doing it, either, but this time I put my job on the line. Fire my butt out of here, I told ’em, but as long as I’m here, the kid’s at short every day.”

The Orioles narrowly missed the playoffs that year, losing out in the last game of the final series to the Milwaukee Brewers. Cal finished with 28 home runs to go along with 93 RBIs and was named the 1982 American League Rookie of the Year. Weaver later told the young infielder that if he had started him at shortstop earlier in the season they would have probably won the pennant.

It was also during this time that Ripken and Eddie Murray established their lifelong friendship. Murray had known Cal Sr. since the early 1970s. The elder Ripken had backed Eddie when the Oriole organization was hesitant about allowing the slugging infielder to become a switch-hitter.

Murray enjoyed standing around at the shortstop position after he had taken infield practice, and that is where he and Cal first started talking baseball. The veteran’s guidance had the immediate impact of helping Ripken relax on the field. The Birds’ Hall of Fame first baseman also counseled the young player on how to conduct himself on and off the field as a major league ball player.

With Cal hitting third and Eddie Murray batting cleanup the Birds won the American League East pennant by 6 games. Ripken led the league with 211 hits while compiling a .318 batting average to go along with 27 home runs and 102 RBIs. His stellar season earned him the American League’s Most Valuable Player award, finishing a few votes ahead of Murray. The Orioles knocked off the Chicago White Sox in the playoffs and went on to defeat an aging yet star-studded Philadelphia team in the Fall Classic. Junior snagged a line drive off the bat of Garry Maddox for the final out of the series.

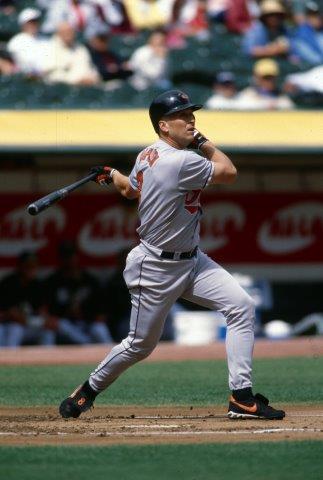

For the next few years, Cal continued to establish himself as the Orioles’ everyday shortstop. He was taller and heavier than the majority of players who had previously played the position. Nevertheless, Ripken’s agility and quick reflexes made baseball experts reconsider the preferred size of future major league shortstops.

With the bat, Ripken’s power numbers surpassed nearly all of the shortstops that had previously come before him. There were certainly great hitters who played the position in years past, but his unique combination of power [431 career home runs] and patience [1,129 career walks] put him in a class all by himself.

Cal’s strength as a defensive player was his ability to play the batter. Knowing each hitter’s tendencies at the plate and playing them accordingly allowed him to station himself at the right place on the field. He was able to hone this useful skill by attending the pitcher-catcher strategy sessions the Orioles held in the clubhouse before each series. Very seldom, if ever, was he seen out of position or cheating the wrong way on an opposing batsman.

Ripken Sr. took over as the Baltimore manager in 1987. The Orioles had Junior anchoring the shortstop position and Billy Ripken, who joined the ballclub that year, at second base. The brothers covered the middle in fine style, forming one of the most sure- handed double play combinations in the history of the organization.

Late in the season, on September 14, Ripken Sr. decided to give his son a rest in the last inning of a game that the Orioles were losing badly in Toronto. The Oriole shortstop had not missed an inning of play dating back to June 5, 1982. Cal was standing on the dugout steps waiting to take his place at the on-deck circle when Senior mentioned to him that this might be a good time to take a rest. Junior, who was in a 1-for-12 hitting slump before the game, took his turn at bat in the top of the eighth inning and then had a seat on the bench. Oriole utility man Ron Washington went in to play shortstop in the bottom of the inning, ending Cal’s consecutive innings streak at 8,264.

When asked why he made the move, Ripken Sr. replied, “I’ve been thinking about it for a long time. I wanted to take the monkey off of his back. It was my decision, not his.”

When the subject of his removal from the game was brought up to Cal, he said, “ I’m a player, I do what my manager tells me to do… It was a surprise but I didn’t feel that I needed an explanation… It just so happens that in this case, my father is the manager.”

The Orioles limped into a sixth-place finish, and it was tough year for Cal as well. His consecutive innings streak ended, and two weeks later he was ejected from a game for the first time in his career. Although Ripken hit 27 home runs with 98 RBIs, his batting average was barely over .250.

On a more pleasant note, when the season ended Cal married the former Kelly Greer on November 13, 1987, in Towson, Maryland. The couple had their first child, Rachel, in 1989, and their son, Ryan, came along in 1993.

After losing the first six games, of what was supposed to be a rebuilding year in 1988, Oriole manager Cal Ripken Sr. was fired by owner Edward Bennent Williams. Cal and Billy were both taken aback by the short string that had been placed on a man who had dedicated his entire baseball career to the Baltimore organization. The Ripken brothers shook off the sting of the owner’s quick trigger and went about their business on the field.

Years earlier Junior first started giving instructions to Oriole pitchers on how to pitch opposing batters. The Birds’ young starter Storm Davis was having trouble against Boston and New York and went to Ripken for advice. Cal wrote out the preferred pitch sequence for the entire Boston lineup on a piece of paper and gave it to Davis before the game. The Oriole right-hander ended up shutting down the Red Sox that night, proving the old axiom that a ballplayer can help his team win in a variety of ways.

A few years later, Ripken worked out a plan with Oriole catcher Chris Hoiles to call the pitch sequence during the game. Junior would flash the prearranged set of signals to the Oriole backstop, who in turn relayed them to the pitcher.

For the next few seasons, Cal continued to anchor the Oriole infield, and in 1990 his .996 fielding percentage at shortstop was the highest in the history of the game. Ripken made only three errors in 680 chances, but amazingly he didn’t win the Gold Glove. He accepted 428 consecutive chances that year without making an error.

Ripken started off the 1991 season on a torrid hitting pace and stayed hot all year. As July approached, the fans voted him to his ninth consecutive All-Star team [eight of them as a starter.] Initially, he was a bit hesitant about accepting an invitation to appear in the annual Home Run Derby. Ripken eventually agreed to participate in the event, blasting 12 home runs and becoming the first shortstop to win the derby crown. The following day, Cal’s three-run homer in the third inning off of his former Oriole teammate Dennis Martinez propelled the American League to a 4-2 victory in the Mid-Summer Classic. He was the first player to win the Home Run Derby and the All-Star Game MVP award in the same season.

Ripken finished the year with 46 doubles, 34 home runs, 114 RBIs, and a .323 batting average. These outstanding numbers earned him his second American League MVP award. He also finished with a .986 fielding percentage and was awarded his first Gold Glove.

The Orioles moved from Memorial Stadium to Camden Yards in 1992. The Birds’ new ballpark was supposed to be a perfect fit for the gap-hitting Ripken, but he struggled at the plate all year. One of the reasons was the distraction of being in the midst of contract negotiations with the Baltimore front office for most of the season. In addition, he was hit on the elbow by a pitch in April, and in July he was nailed in the back by another errant toss. He finally settled his contract issue in August and although suffering through a subpar year with the bat, his .984 fielding percentage earned him his second Gold Glove.

The 1993 season was the first time that Ripken’s consecutive games streak would be in serious jeopardy. Cal was resilient enough to play through an ankle sprain in 1985 and a twisted ankle in 1992. This time it was a sprained knee, and the continuation of the streak was in serious doubt. The injury occurred during a team brawl with the Seattle Mariners at Camden Yards on June 6. The scene was set when Mariners pitcher Chris Bosio threw behind some Oriole players during the game. In the seventh inning, Oriole ace Mike Mussina plunked Mariner Bill Haselman and the fight was on. Haselman ran towards Mussina as both benches emptied onto the field. When Cal arrived at the mound, he heard a loud pop in his knee as shifted his weight to encounter the charging mass of Seattle players. The fight lasted for what seemed like an eternity, and at some point Ripken ended up on the ground at the bottom of the sprawling pile of players.

Junior finished the game, but the following morning he was barely able to walk. Ripken drove to the ballpark early that day to seek some immediate attention from Orioles trainer Ritchie Bancells. After going through some vigorous physical therapy sessions and exercises, Cal took his place in the Oriole lineup that night. The knee was tested early on a ground ball hit to his right, but he made the play without any pain. The Birds’ durable shortstop continued on for the rest of the game, accepting another tough chance in the last inning.

The All-Star Game was played at Camden Yards later that year. Cal’s offensive statistics were not overwhelming, but the fans still voted him in as a starter. The American League won the contest 9-3.

For the next few seasons, Cal continued to be a stalwart presence in the Baltimore lineup, never missing a game and playing his usual consistent defense in the field.

After many months of contentious negotiations between the owners and the Major League Baseball Players Association [MLBPA], baseball went on strike on August 12, 1994. The main issues at hand were the modern-day baseball magnates’ attempts to impose a salary cap, abolish arbitration, and change the free agency rules. The MLBPA would not sign off on these proposals, leading to the cancellation of the playoffs and World Series. It was the first time in the history of professional sports that an entire postseason was lost due to a labor disagreement.

The situation did not improve over the winter, and there was no resolution in sight by the scheduled start of spring training. The owners threatened to put replacement players on the field to start the 1995 season if the MLBPA did not acquiesce to their demands.

It was at this time that Baltimore Orioles owner Peter Angelos told the press he would forfeit every game before using replacement players. The Birds’ owner had the foresight to realize what the importance of Cal’s consecutive games streak meant to baseball and the Oriole organization.

Ripken had been given permission by the MLBPA to cross the picket line and play in order to keep his consecutive games streak alive, but he declined. Junior had been given the chance to be a replacement player back in 1981 but passed on that opportunity as well. When a reporter asked about him going against the Players Union in order to continue the streak, Cal replied, “My general feeling is that if it’s replacement players, it’s not major league baseball and I won’t be playing.” In a subsequent interview Ripken remarked, “I’ve told myself that if it’s supposed to end, then I need to be strong enough to let it end. If it ends for a good cause, I won’t have any regrets. I won’t look back… I won’t ask myself what if. I’ll just let it end and I’ll move on. It’s my decision, and I’ve made it.”

Thankfully, the decision of playing out the 1995 season sans labor agreement was settled in a court of law instead of across the negotiating table. Future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor ruled in favor of starting the games until an amicable resolution could be worked out between the two warring parties.

The season started in late April, and it was soon apparent that if Cal stayed injury-free he would break Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak in September.

As the year progressed, some deranged individuals began to come out of the woodwork. On Wednesday, August 25, a man claiming to be Lou Gehrig Jr. called the Seattle Kingdome and said he would shoot Ripken if he played that night.3 Cal took the field as usual that evening and was not told about the menacing phone call until after the game. There was another threat made on Cal’s life when the team was playing in Boston, but Oriole officials did not tell him about that call either. Junior spoke to the press about the incident saying “he preferred not knowing about the threats and that he just accepted them for what they are.”

Speaking further about the incident, Ripken remarked, “It’s like anything else you have to deal with. It’s something out of your control. Its something that you have to think about, you have to take certain precautions and you have to deal with it. In the very best world, I’d like to think that I’m just a baseball player and be like everybody else. I think of myself just like everybody else. But when something like this happens, you have to think about things in a little bit different way. I’m not going to let it affect the way I’m playing. I’m not going to let it inhibit the way I live my life.”

As Cal made way his way closer to the magic 2,131 number, a banner was hung on the side of the B&O warehouse in right field at Camden Yards denoting the number of his consecutive games.

On September 5, 1995, Cal tied Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak of 2,130. Former Oriole manager Earl Weaver threw out the first pitch in front of a sold-out Camden Yards crowd. When the warehouse banner was unfurled to 2,130, Cal received a four-minute standing ovation. Ripken smacked three hits in the game, including a home run in the sixth inning. When asked by a reporter about hitting a homer in such a monumental game, Ripken replied, “I’m not in the business of script-writing but if I were, this would have been a pretty good one.”

After the game, pitcher Jim Gott presented Junior with the ball from his first major league win—against the Orioles on May 30, 1982, the same day the streak started.

The next night, the record-breaking evening started out with Cal’s two children throwing out the ceremonial first pitch. Ripken’s parents and family along with President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and the immortal Joe DiMaggio were present for the historic event. In the bottom of the fourth inning, Cal bashed a home run over the left field wall, the Oriole Park faithful erupting with cheers as he circled the bases.

The loudest applause for Ripken occurred when the warehouse banner was unfurled to 2,131 amidst a shower of fireworks at the end of the top half of the fifth inning. After numerous curtain calls, Cal was pushed out onto the field by Rafael Palmeiro and Bobby Bonilla. What followed can only be described as one of modern baseball’s greatest moments. Starting out on the first base side of the field, Cal began his now famous lap around the inside of Camden Yards. He high-fived many of the fans that ringed the lower box seat area while waving to the rest of the crowd along way. The Oriole Park hurrahs for baseball’s new Ironman lasted over 22 minutes.

Over 5.1 million households tuned in to watch Cal break Lou Gehrig’s record that night. Baseball enthusiasts from all over the country were proud of the local boy that got to live out his dream of playing for his hometown team. The positive synergy from this fall night in Baltimore all but erased the bitter memories of the 1994 strike.

When asked about his trek around Camden Yards, Ripken replied, “Being there and seeing the enthusiasm up close was really something meaningful. It was an unbelievable experience.”

To put Ripken’s consecutive games record into some type of statistical perspective, 3,713 major league players went on the disabled list during the 13 years that the streak encompassed.

Cal’s record-breaking achievement earned him plaudits from United Press International, The Associated Press, Sports Illustrated, ESPN, Newsweek and others. The New York Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America voted him the “Toast of the Town Award,” the first time that someone other than a New Yorker received the honor.

The Orioles started out the 1996 campaign playing great baseball under new manager Dave Johnson. A few months into the season, Cal passed another milestone in baseball history. On June 14 in a game at Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City, he broke Japanese player Sachio Kinugasa’s world record of 2,215 consecutive games.

A month later, Johnson moved Cal to third base and started rookie infielder Manny Alexander at shortstop in a game against Toronto. Many baseball insiders had Alexander penciled in as Ripken’s replacement at shortstop. However, it soon became apparent that the young player was not ready to assume the role.

Overall, the Orioles had a good year in 1996, finishing four games behind the first-place New York Yankees. Cal hit .444 in the first round of the playoffs as the Birds sent Cleveland packing in four games. The American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees was a different story. The Baltimore bats were shut down by strong Yankee pitching, as the Orioles lost the series four games to one.

The Orioles acquired shortstop Mike Bordick in the off-season, and Ripken made the permanent switch to third base. The team started out the 1997 campaign playing great baseball and kept a tight grip on first place for the entire year. It was also the last time that Baltimore made the playoffs during Cal’s tenure with the team. The Orioles beat the Seattle Mariners to open the postseason, and Cal led the club with a .438 batting average. The Birds’ third sacker stayed hot against the Indians in the next round of the playoffs, hitting .348. However, Cleveland outplayed Baltimore, coming out on top in six games, putting an anticlimactic end to the Orioles’ wire-to-wire season.

Junior continued his consecutive games streak up until the end of the 1998 season. On September 20 Ripken had a private meeting with Oriole manager Ray Miller and asked to be taken out of the lineup against the New York Yankees. It was the last home game, and Cal figured it was the best way to end all of the speculation over the winter about when he would finally sit out a game. This rare night off ended Ripken’s consecutive games streak at 2,632.

The following year started off on a sad note for Cal and his family as his father passed away on March 25 from lung cancer. The grieving Oriole legend also persevered though some nagging injuries that limited his playing time. Through it all, he still managed to post a career-high batting average (.340) while hitting 18 home runs in 332 at-bats. Ripken also garnered six hits in an interleague game against Atlanta, one shy of the Oriole record.4

Cal continued to play third base for the Orioles at a high level, but it was soon apparent to Baltimore baseball fans that all good things must come to an end. In June of 2001, Ripken announced that he was retiring at the conclusion of the season. In July, he was named to his 19th All-Star team. In a truly classy gesture, American League shortstop Alex Rodriguez switched spots with Ripken, who was playing third base, allowing Cal to start the game at his former position. Junior homered in the third inning off of Chan Ho Park leading the American League squad to a 4-1 victory. The veteran infielder was named the game’s Most Valuable Player for the second time in his career.

Cal continued to play third base for the Orioles at a high level, but it was soon apparent to Baltimore baseball fans that all good things must come to an end. In June of 2001, Ripken announced that he was retiring at the conclusion of the season. In July, he was named to his 19th All-Star team. In a truly classy gesture, American League shortstop Alex Rodriguez switched spots with Ripken, who was playing third base, allowing Cal to start the game at his former position. Junior homered in the third inning off of Chan Ho Park leading the American League squad to a 4-1 victory. The veteran infielder was named the game’s Most Valuable Player for the second time in his career.

Because a number of games were canceled due to the September 11 terrorist attacks, Ripken’s retirement ceremony was held on October 6, 2001, at Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Quite often, teams schedule these tributes after the player has retired and against a poor-drawing opponent to pad the attendance. Orioles owner Peter Angelos saw to it that Ripken’s farewell festivities were held during his last home game and against the Boston Red Sox.

Cal’s lifetime major league accomplishments include 3,184 hits and eight Silver Slugger awards, given out annually to the best offensive player at each position. Ripken also holds numerous fielding records at shortstop, and in 1999 he was named to the All-Century team.

Ripken has done a considerable amount of charitable work since he retired from baseball. In 2001, he and his brother Bill formed the Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation. The goal of the foundation is to give underprivileged children the chance to learn baseball through clinics and camps. Cal has also entered the business side of the game, purchasing financial interests in minor league baseball teams. Locally, he is the owner of the Aberdeen Ironbirds, an Oriole affiliate. In addition, he runs a state-of-the-art youth baseball facility that is adjacent to Ripken Stadium.

After waiting the required five years, Cal was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first ballot, garnering 537 of 545 first-place votes in 2007. More than 75,000 loyal fans traveled to Cooperstown to witness the inductions of Ripken and San Diego Padres icon Tony Gwynn.

Also in 2007, Cal Ripken Jr. was named Special Sports Envoy for the State Department by President George W. Bush. During a trip to China, Cal and a number of former major leaguers put on baseball clinics for over 800 Chinese children. Their efforts were chronicled in the documentary film A Shortstop in China.

The Ripken family continues to perform philanthropic work through the Cal Ripken Sr. foundation, which donates to various charities including the RBI program that brings youth baseball to kids in the inner city.

Last updated: April 3, 2011

Sources

I would like to thank Bill Haelig for sharing his vast knowledge of Cal Ripken and his career.

Baltimore Sun

The Sporting News

York Daily Record

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Baseball-Reference.com

WSBA Talk Radio Oriole Magic Baseball Guide

1987 Orioles Media Guide

Kurkjian, Tim; Verducci, Tom; Fimrite, Ron; Wiley, Ralph; and Whiteside, Kelly. Sports Illustrated Presents, 2,131 Cal Ripken Stands Alone

Athlon Sports Magazine 2001 Preview

Ripken, Cal, and Donald Phillips. Get in The Game. New York: Gotham Books, 2007.

Ripken, Cal Jr., and Mike Bryan. The Only Way I Know. New York: Viking Press, 1996.

Rosenfeld, Harvey. Iron Man, The Cal Ripken Story. New York: St. Martins Press, 1995.

Photo credits: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, The Topps Company

2 He won the Puerto Rican League MVP award in 1981 while playing for Orioles pitching coach and later manager Ray Miller’s Caquas team.

3 Lou Gehrig married Eleanor Grace Twitchell in 1933, and the couple had no children.

4 On June 10, 1892, Oriole catcher Wilbert Robinson went 7-for-7 in the first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns.

Full Name

Calvin Edwin Ripken

Born

August 24, 1960 at Havre de Grace, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.