Baseball’s First Commissioner: The Hiring of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

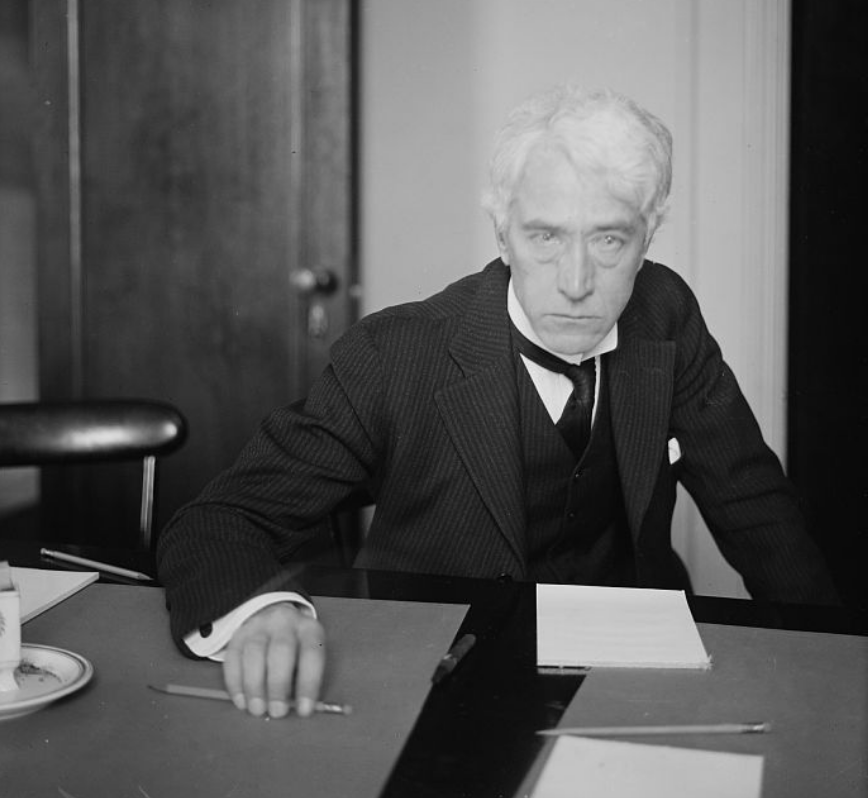

Federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was hired as baseball’s first commissioner in November 1920. He served in that role for nearly a quarter-century until his death in 1944. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Only in the face of extreme chaos and discontent will people relinquish power to an outsider. In 1920 baseball’s owners found themselves in just such a situation. After nearly two decades under a makeshift governance system, multiple factions of owners were publicly feuding and even challenging each other in court. The final few years had been particularly embarrassing, and the magnates were ready to accept almost any resolution that would restore order and confidence to their business.

Baseball’s governance had been inaugurated in 1903 as part of the peace agreement between the established National League and the upstart American League. Including the affiliated minor leagues, the new structure was dubbed Organized Baseball, and the governing document was the National Agreement. For its governing body, the owners created a three-person panel, the National Commission, that included the league presidents: Harry Pulliam, the recently elected compromise-candidate president of the National League, and Ban Johnson, the motive force behind the American League. Johnson was smart, driven, and tough — he had boxed as a youth — with a streak of self-righteousness.

The third was more problematic. The owners wanted someone connected with baseball ownership, and thus one of their own, but with the latent hostility between the leagues, both sides were leery of selecting someone associated with the other. Cincinnati Reds President Garry Herrmann turned out to be the perfect compromise choice. Despite his affiliation with the National League, Herrmann was acceptable to Johnson because of their friendship from Johnson’s time in Cincinnati and the pragmatic way he helped negotiate the peace agreement between the leagues. Though he was often photographed with a dour expression, Herrmann was an outgoing, big-spending, machine politician who enjoyed life’s pleasures.

With the settlement behind them, for the next dozen or so years the two leagues carried on a more or less friendly rivalry with steadily rising profits for all. The National League continued to govern itself as a mostly dysfunctional democracy. The league purposely kept its league president as little more than a figurehead for major decisions, with his authority typically limited to overseeing the umpires and player disciplinary issues. On important league matters, the owners generally ignored the league president and bickered among themselves to reach a resolution. Conversely, Johnson ran his organization as a constitutional monarchy. Most of the owners were beholden to him for the original purchase of their franchises and occasionally for financial support. With its better organization and leadership, the American League thrived during its first decade of existence and soon overtook the Nationals in attendance. As the AL thrived, Johnson became the first among equals on the Commission and the most powerful man in baseball.

One of the more unrewarding duties of the National Commission was adjudicating player control issues. No matter the outcome, someone was going to be unhappy. These hearings were often over intricate, tangled particulars. Amateur players could sign with major-league teams, affiliated minor-league teams, independent minor-league teams, or company teams, or enroll in college, and they would occasionally sign contracts with more than one. Teams, too, would assign contracts to other teams in other leagues, and this was not always perfectly tracked either.

A dispute over future Hall of Fame first baseman George Sisler caused one of the first significant rifts between an owner and the Commission. After signing with Akron in a low minor league, Sisler changed his mind and enrolled at the University of Michigan, where Branch Rickey was the baseball coach. Akron sold his contract to Columbus, and in 1912 Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss purchased his contract from Columbus. Sisler excelled at Michigan, and he wanted out of his contract with Pittsburgh and to be declared a free agent. He took his case to the Commission, where he retained legal representation, and enlisted Coach Rickey to help him through the proceedings. The Commission sided with the youngster, ruling that Sisler’s father had not consented to the contract, which George had signed while still a minor. Most galling to Dreyfuss, Sisler signed with the AL’s St. Louis Browns, now managed by none other than Rickey. In response, Dreyfuss charged the Browns with tampering. Once again, the Commission ruled against him. With this second adverse verdict, Dreyfuss lost faith in the Commission as constituted and vowed to oust Herrmann when the opportunity arose.

A few years later another fallout over player control wracked the Commission. In 1917 the NL’s Boston Braves conditionally purchased pitcher Scott Perry from minor-league Atlanta for $2,500, $500 up-front and $2,000 later if they kept him. After riding the bench in Boston without playing for a couple of weeks, Perry jumped to the company team of American Steel and Wire. After the 30-day conditional period, with Perry still playing for the company team, Atlanta prodded Boston for payment; Boston refused. At the time, the National Commission and Herrmann independently weighed in with some contradictory opinions over Perry’s precise status, some formal and some informal, leaving uncertainty over who held his rights.

In March 1918, with Perry back in Organized Baseball, Atlanta sold him to the AL’s Philadelphia Athletics. When Perry excelled in Philadelphia, Boston attempted to reclaim him. Philadelphia maintained that he was theirs. With Herrmann as the deciding vote, Perry was awarded to Boston. Unwilling to accept the result, the Athletics broke precedent and — encouraged by Johnson — obtained a temporary injunction in civil court against Perry going to Boston.

National League President John Tener (who had taken on this role in 1913) was so dismayed that he recommended canceling the World Series if Philadelphia did not relent. The NL owners were not willing to go that far, and when Philadelphia held firm, Tener resigned. Once all sides realized the damage they were causing, the parties reached a settlement: Philadelphia would keep Perry, drop the civil case, and pay Boston $2,500. Herrmann’s dithering and contradictory messages cost him respect and support on all sides, and the NL owners became further embittered toward Johnson. For its next president, the NL promoted league secretary-treasurer John Heydler, a fine administrator but one with little control or authority over his owners.

The end of the season and the World War brought additional conflicts over player disposition. When the minor leagues cut short their schedules during 1918, the Commission had approved major-league teams (themselves struggling to staff their war-depleted rosters) signing now idle minor leaguers for the balance of the major-league season. Unfortunately, the Commission did not formally address the future rights around any player so employed. After the season White Sox owner Charles Comiskey expected to keep pitcher Jack Quinn, who had started the season with the minor-league Vernon Tigers in the Pacific Coast League and finished strongly with Chicago. After the season, the Vernon Tigers, who believed they still held Quinn’s rights, sold him to the Yankees.

All three concerned clubs appealed to the Commission. On this mostly American League matter, Heydler and Herrmann mostly deferred to Johnson. When the Commission ruled for New York, Comiskey was irate and now fully hardened against Johnson. The two had been friends since their nineteenth-century days, when they had built up the old Western League, and they had bonded further as they turned the league into the now-major American League in 1901. Since then their relationship had cooled; it was now ruptured irrevocably.

American League president Ban Johnson had served as the de facto leader of baseball’s governing body, the National Commission, for the first two decades of the 20th century, but by 1920 his power and his popularity among the team owners had greatly deteriorated. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

*****

It was not only player-control controversies that drained confidence in the National Commission. In late 1913, with the self–declared major Federal League about to start competing with the two existing major leagues, the long-factionalized NL jettisoned league President Thomas Lynch. Another compromise candidate, Lynch had been elected in December 1909 but soon lost his support.

Most of the owners wanted a new, higher-profile president. The magnates believed that an outsider with prestige could help guide them, mainly because it might be harder to simply ignore him. They were not so much worried about giving a new president too much power; they were more concerned about getting someone who could exert at least some measure of authority. By tripling the league president’s salary, the NL landed Tener, then governor of Pennsylvania and a physically imposing 6-foot-4, 240-pound one-time major-league pitcher.

The Federal League threw in the towel in 1915 after two seasons, but the battle and the settlement had been costly to Organized Baseball, while exacerbating lingering tensions among the owners. There were also two AL franchises with new owners that were neither beholden nor deferential to Johnson: Harry Frazee in Boston and Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston as co-owners in New York. Things were not helped when prosperity did not return to the AL and NL in 1916 after the demise of the Federal League. Moreover, the players were disgruntled and restless as their salaries were slashed to prewar amounts.

America’s entry into World War I further dented the owners’ pocketbooks and highlighted their disorganized leadership. In late May 1918, US Provost Marshal Enoch Crowder issued a “work or fight” order. This edict required all military age men (defined as ages 21 to 31) to either enlist, find employment in an “essential” industry, or become subject to immediate conscription. Organized Baseball appealed this decree, arguing that it should be exempt, like the theater industry. On July 20, Secretary of War Newton Baker ruled against them, affirming that baseball players were subject to the work-or-fight order.

Although Baker did not require that baseball cease operations, several baseball executives panicked and declared an immediate end to the season. Johnson ordered the American League season canceled. National League President John Tener and National Commission Chairman Garry Herrmann felt likewise, but did not assume the same unilateral authority. They refrained from any public declaration without first consulting their league’s owners. Johnson’s hasty proclamation terminating the season prompted the first real questioning of his authority and judgment. Very few owners wanted to take this drastic step. They simply ignored Johnson and played the scheduled games over the next few days. Once Johnson realized the owners were ignoring him, he backtracked, advising owners to keep playing until notified to cease. But the magnates still had no overall strategy on how to wind up the schedule.

Frustrated with Johnson’s leadership, a delegation of owners hastened to Washington for another appeal to Crowder and Baker, and the government agreed to extend the deadline to September 1. Johnson now wanted to end the season on August 20 to allow time to play a World Series before that date. Herrmann favored playing the season through September 1 and hoping for an extension for the World Series players (which was eventually granted at the eleventh hour). Many other National League owners were willing to scrap the Series; they reasoned that the team rosters would be so unrecognizable that a World Series would be meaningless and would garner little public interest.

On August 2 the National League met and decided to play the season through Labor Day, September 2, with the World Series to follow, provided an agreement could be reached with the American League. The group deputized Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss to work out an arrangement with the American League and agreed to abide by whatever he negotiated. Johnson, Frazee, and the rest of the American League owners met the following day in Cleveland to hash out their schedule. Johnson vehemently advocated ending the regular season on August 20, with the World Series to follow. Frazee, Comiskey, Washington owner Clark Griffith, and the Yankees owners, Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, favored the National League plan; more games meant more revenue, a crucial consideration in this money-losing season. The four owners prevailed as Johnson lost his first real showdown within his league.

The 1918 World Series itself led to further embarrassment for the Commission. The players were angry about the reduced World Series shares they would receive under a new distribution plan. At the previous year’s winter meetings, the owners had hoped to energize end-of-season interest among fans and stimulate competition among teams eliminated from the pennant. To that end, they reallocated a portion of the players’ World Series shares to players on the other first-division teams (second through fourth place). The owners had projected that the winners would each receive $2,000 and the losers $1,400 — well below recent World Series shares. Based on attendance over the first few games, it was clear that receipts would fall short of even those estimates.

The morning before Game Five of the World Series — which was between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs — the Commission reluctantly granted Boston’s Harry Hooper and Chicago’s Les Mann an audience at their hotel. The two players presented their case asking for shares of $2,000 and $1,400 regardless of final attendance. Johnson, speaking for the Commission, dismissed them, telling them to go to the ballpark and play. After rehashing the matter in their respective clubhouses, the players refused to start the game until they had a follow-up meeting with the National Commission.

When the commissioners arrived at Fenway Park and realized the players were not coming out to play, they hastily called a meeting in the umpires’ dressing room. A confused assemblage jammed into the tiny quarters. The participants and onlookers included player representatives Hooper and Mann; Johnson, Herrmann, and Heydler; Boston manager Ed Barrow; Boston’s mayor; assorted reporters; and even curious fans. In front of this hodgepodge, Hooper argued that the players should receive the shares estimated earlier, and that the new formula including the nonparticipant teams should be shelved until after the war.

Herrmann and Johnson had both arrived well-oiled after a morning of imbibing with friends at the hotel. Herrmann began by retelling the National Commission’s glorious history. A sloppy, teary Johnson interrupted Herrmann, threw his arm around Hooper, made a rambling appeal to the players’ patriotism and then told them to get out on the field. Hooper and Mann realized there was little opportunity for compromise with the Commission in its incapacitated state. The players unhappily concluded that they had little option but to back down. With so many witnesses, this undisciplined episode did little to enhance the prestige of the Commission.

By the end of the 1918 season, Johnson’s once widespread support from his owners was eroding. Comiskey was hoping to depose him. If not yet fully alienated, the Yankees owners, too, were growing frustrated. They believed they should have had a shot at buying star outfielder Tris Speaker a couple years earlier when Johnson orchestrated his sale from Boston to Cleveland. At this point, however, Johnson’s most active foe was Harry Frazee. Johnson and Frazee had clashed from the start, and Johnson seized on the gambling problem in Fenway Park in 1917 as a pretext (with some legitimacy) to censure Frazee. Frazee’s outspoken criticism of Johnson’s mismanagement of the 1918 season made matters even worse. With the season over, Johnson began actively campaigning to oust Frazee from ownership of the Red Sox and was searching for a buyer.

The NL had its own troublesome episodes. In August 1918 Reds manager Christy Mathewson suspended first baseman Hal Chase for erratic play that appeared suspiciously like throwing games and for trying to bribe opposing players. Baseball’s owners had little interest in publicly airing this sort of dirty laundry and resolution of Chase’s case dragged on for several months. Eventually Heydler assembled everyone for a secret hearing in January 1919. Despite the testimony of several witnesses, Heydler cleared Chase of any wrongdoing. Most attribute Heydler’s exoneration to Mathewson’s absence and inability to testify in person (he was in France with the AEF — though he had signed an affidavit outlining his charges), the subjectiveness of the evidence, Chase’s accompaniment by three attorneys who produced multiple character witnesses, the lack of precedents in dealing with crooked players, and the owners’ desire to keep such shenanigans under wraps — especially without overwhelming evidence.

The minor leagues were chafing as well. After the financially disastrous 1918 season, the high minor leagues openly rebelled against the major-league/minor-league draft (the remnant of which today is the Rule 5 draft). The draft gave the majors the right to select players from the minors, a sore spot since its inception. The minors refused to renew the National Agreement unless the draft was removed or materially modified. When they couldn’t reach agreement, the two sides agreed to let the National Agreement lapse, but separately and informally arranged to mutually respect each other’s territorial and player reservation rights. Once again, baseball’s leadership appeared unable to manage their affairs.

Two owners went so far as to independently pursue an alternative to the National Commission. Frazee and New York Giants President Harry Hempstead — also unhappy with baseball’s muddled response to the war and starting to market his team for sale — approached former President William Howard Taft about becoming a “one man National Baseball Commission,” an administrator who would oversee all of baseball. At this time, the idea was premature and accomplished little except to further infuriate Johnson. In retrospect, it is hardly surprising that with two members of three-person panel being in power for such a long period of time, resentments would develop. But the baseball magnates were not yet desperate enough to hand their oversight to an outsider.

Former US President William Howard Taft, seen here throwing out the first pitch at a Washington Senators game on Opening Day 1910, was one of many prominent figures who were rumored to be candidates for the role of baseball commissioner at the end of the decade. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

*****

Baseball’s owners might not have yet been ready for a full-scale overhaul of their governance, but the NL magnates in particular were getting antsy to unseat Herrmann. With no obvious alternative and Johnson’s active support, the NL agreed to give him one more year. To avoid a replay after the 1919 season, the owners tasked Johnson and Heydler to come up with some neutral candidates during the year for the Commission chair. Johnson’s position was about to become more tenuous as well. Frazee was against him, Comiskey had made a final break with the Quinn decision, and Johnson was about to irreparably rupture his relationship with the Yankees owners.

Red Sox star pitcher Carl Mays had an emotionally draining first half of the 1919 season: His mother’s house burned down; he endured a lengthy holdout to garner his $8,000 salary; and he was frustrated by his lack of run support. In early July, Ban Johnson fined him $100 for a Memorial Day incident in which Mays threw a ball at a heckler in the grandstand. Mays soon returned to the mound, and on July 13 his erratic behavior ignited a crisis in the American League boardrooms.

In the second inning of a game in Chicago, Mays was hit in the back of the head on the catcher’s throw down to second to nab a basestealer. After the inning, he disappeared into the clubhouse, where he suffered a nervous breakdown. Mays disappeared back to Boston by train, picked up his wife and luggage, and headed for his in-laws in Pennsylvania for some rest and relaxation.

The other AL clubs inundated Frazee and Barrow with purchase and trade offers for the AWOL hurler, and Frazee recognized an opportunity to cash in. These clubs, and others, were offering players, cash, or some combination of the two. Johnson was aghast at the wholesale pursuit of a player he believed should be suspended. One of his core beliefs concerned proper player and manager behavior, which was abysmal during the 1890s when he developed his convictions. That a player could abandon his team and force a favorable trade offended his principles. Johnson contacted the clubs and demanded that they cease negotiations with Boston. Those owners still loyal to Johnson complied. The Yankees and White Sox, however, whose deference to the president had waned, ignored Johnson’s directive.

At the end of July, Boston sent Mays to the Yankees for $40,000 and two pitchers, ranking with the highest prices ever paid for a ballplayer. The teams that had withdrawn from negotiation at Johnson’s request were obviously annoyed with this result. Johnson was furious; he had expected Boston would suspend its wayward pitcher. With the announcement of the trade, Johnson promptly suspended Mays indefinitely, the prerogative of the league president.

For the second time in two years, an American League owner took a grievance to the civil courts. For the first time, however, it was directed against Johnson, generally regarded as the most powerful man in baseball. The Yankees owners requested that the court enjoin Johnson from any action that would prevent Mays from playing in New York. On August 6 the court issued a temporary injunction that prevented Johnson from suspending Mays. The subsequent court hearings were particularly bitter. On October 25 the court ruled in favor of the Yankees owners, permanently enjoining Johnson from interfering with Mays. Not surprisingly, this did not end the battle. Johnson appealed the decision and withheld the Yankee players’ third-place share of World Series receipts.

The American League was now in open civil war. The anti-Johnson faction consisted of the Yankees (Ruppert and Huston), the Red Sox (Frazee), and the White Sox (Comiskey), and were labeled the “Insurrectos.” The other five franchise owners remained loyal to Johnson, hence their nickname, the “Loyal Five.” Without enough votes to unseat him, the Insurrectos used league meetings to aggressively propose anti-Johnson legislation and lawyered up, filing multiple lawsuits against the president to drive him from office. The Loyal Five supported Johnson and worked to neuter the Insurrectos, bringing in their own posse of attorneys. In February 1920 the two factions reached a truce: Johnson kept his job, but an oversight committee of Ruppert and Griffith was named, moderating his dominance (and the Yankees players received their third-place World Series shares).

With Johnson fighting for his political life and AL owners consumed with their internal struggle, the NL owners forced Herrmann’s resignation in January (not that many AL owners favored the National Commission status quo in any case). With his exit the National Commission essentially ceased operation. Once again, Johnson and Tener headed a search committee to find a replacement; in the meantime, baseball was left operating without effective governance. The list of possible candidates for the chair included Taft, generals, senators, government officials, and other eminent citizens. Heydler’s preferred candidate was Chicago federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Johnson, however, procrastinated. After nearly two decades of being the Commission’s dominant voice, he hoped to orchestrate an ally into the role. One later account had him maneuvering to get the chairmanship for himself.

Baseball played the 1920 season without a Commission chairman, and the owners were getting antsy. Before they could enforce some sort of resolution on Johnson and Heydler, however, events intervened, changing the nature of what they wanted in governance. Had a new chairman been named during the season, it is likely that the Commission structure would have survived the coming revelations.

In September 1920, a Cook County (Chicago) grand jury was called to probe a suspicious Chicago Cubs-Philadelphia Phillies game. Directed by Judge Charles A. McDonald, the investigation quickly expanded to investigate the possible throwing of the 1919 World Series by the White Sox. Details quickly emerged, and within a month, confessions by three White Sox players (including Shoeless Joe Jackson) made it clear the Series had been fixed. For the last several years baseball’s owners had squabbled among themselves and no longer trusted their leadership. Now, they had a broader problem — the public could no longer trust their product.

*****

In the settlement with the Federal League, Charles Weeghman, owner of Chicago’s FL franchise, was given a short-term option to buy the Cubs. As his deadline approached, Weeghman turned to Albert Lasker, a Chicago advertising executive whose interest in baseball and ability to raise money was well-known. Lasker agreed to ante up the necessary $150,000 on two conditions: He would be allowed to approve the board of directors, and Lasker’s personal attorney, Alfred Austrian, would be the team’s attorney. One of the investors he demanded for the board was chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley, who later bought Weeghman out when he ran into financial difficulties.

After watching the National Commission in action for a couple of years, and the constant sniping from those affected by their decisions, Lasker believed baseball needed a new governmental structure. In 1919 he proposed that a triumvirate of prominent citizens, none with a financial interest in the sport, be granted absolute powers. As with Frazee’s and Hempstead’s earlier outreach to Taft, at the time most owners had little interest in assigning this type of authority and control to outsiders.

Now, with the Black Sox game-fixing becoming public, many owners reconsidered this more radical restructuring. A core group of owners were convinced of the plan by the end of September: the AL’s Insurrectos along with Pittsburgh, New York, and Chicago in the NL. The rest of NL owners and Heydler quickly jumped on board (in total, the “Eleven”). In the AL, the truce burst open, with Johnson and the Loyal Five resisting any change to the governing structure. The Loyal Five stood with him out of allegiance but also because there was always a risk in turning one’s affairs over to someone without skin in the game. As a fallback position, Johnson hoped to keep the Commission intact and install his friend Judge McDonald, who had presided over the grand jury investigation, as chairman. When the Lasker plan became fait accompli, Johnson hoped to secure the new committee chair for McDonald.

On October 18 the Eleven held a joint National and American League meeting boycotted by Johnson and the Loyal Five. They decided to move ahead with or without the Loyal Five: If an agreement could not be reached by November 1, the Insurrectos would withdraw from the AL and join a reconstituted and enlarged NL; a 12th team would be added in one of AL cities; and they would move forward with the Lasker governance plan, proposing a $25,000 salary for the chairman, $10,000 for the other two.

Over the next couple of weeks, fast and furious negotiations took place between and among factions and individuals as the magnates simultaneously postured and searched for a resolution. Among themselves, the Eleven decided on Landis to lead the new committee. Preliminary indications, however, suggested that it would take a salary well above $25,000 to induce him to accept the job. Already one of the best-known judges in the country, Landis had presided over the Federal League’s antitrust and conspiracy suit against Organized Baseball in 1915. Landis let the case drag on throughout the year without issuing a decision, freeing baseball from having to make the unwelcome policy changes that would have come from an adverse ruling. When the Feds threw in the towel after the season, the suit was dismissed, and baseball could continue business as usual. (The Baltimore Federal League franchise later filed another antitrust suit that was not resolved in Organized Baseball’s favor until 1922.)

The baseball bosses appreciated the significance of Landis’s approach. “It seemed to me,” Huston wrote Landis days after he became commissioner, “that your delay in rendering the decision showed not only your love of the national game, but indicated that you possessed excellent judgment.”1

The November 1 deadline came and went without an agreement. The Loyal Five proposed a nine-man commission — three from each league and three from the minors — to hash out a new governance structure. They also declared that if the Insurrectos bolted they would install new franchises in New York, Boston, and Chicago — an incredibly costly endeavor.

At a meeting in Chicago on November 8, 1920, the Eleven formally voted to create their new league, scrap the National Agreement, adopt the Lasker plan, and offer the chairmanship of the triumvirate to Landis at a salary of $50,000. Choosing the other two was tabled to a later date. They also deputized six owners to call on Landis and sound him out. Johnson addressed the minor-league convention in Kansas City a couple of days later, pushing the Loyal Five’s vision of the future. But his owner allies were tiring of the fight and the huge cost associated with going it alone. Excepting Phil Ball in St. Louis, Johnson’s loyalists had neither the resources nor the desire for a drawn-out battle.

On November 12 the owners of all 16 teams gathered in Chicago without any others present to hash out the final deal, basically along the lines of the Eleven four days earlier. They arranged for a six-person committee to draft a new National Agreement. The owners also realized that it might be difficult to create a commission where some commissioners earned less than others, so they scrapped the three-person concept as too costly, concluding that one commissioner with absolute authority ought to be sufficient. Later that day the full delegation of owners (minus Ball, a Johnson supporter to the last) went to Landis’s courtroom to formally make the offer.

With the owners so obsequiously committed, Landis had the upper hand and knew it. Rather than taking a recess, he kept the magnates waiting while the hearing before him was in session. Once they were all together, Landis told them he wanted to remain on the federal bench. The owners were so desperate that they agreed to this, in effect paying a part-time commissioner $50,000 per year. In practice, Landis’s baseball salary was reduced by his judge’s salary of $7,500, but then returned to him as a $7,500 expense account.

The new National Agreement giving Landis the absolute authority he craved and the “Commissioner of Baseball” title was executed on January 12, 1921. His was the final verdict on all disputes, and he could not be challenged either publicly or in court. The owners retained jurisdiction over making rules and regulations. Baseball had put in place a structure that would last over seven decades. Although the absolute authority of the commissioner would be modified over the years, not until 1992, when Milwaukee Brewers owner Bud Selig was made acting commissioner, did the owners remove outsider oversight and put one of their own back in charge.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Bill Lamb for his review of an early draft of this essay.

Select Bibliography

Many sources discuss all or some of the events highlighted in this essay.

Allen, Lee. The American League Story (New York: Hill and Wang, 1962).

——. The National League Story (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961).

——. 100 Years of Baseball (New York: Bartholomew House, 1950).

Alexander, Charles C. Our Game: An American Baseball History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995).

Brown, Warren. The Chicago Cubs (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2001).

——. The Chicago White Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952).

Burk, Robert F. Never Just a Game: Players, Owners, & American Baseball to 1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

Cook, William A. August “Garry” Herrmann: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

Cruikshank, Jeffery L., and Arthur W. Schultz. The Man Who Sold America (Boston: Harvard Business Review, 2010).

Deveaux, Tom. The Washington Senators 1901-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2001).

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. The Ball Clubs (New York: Harper Perennial, 1996).

——. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002).

——. The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004).

Foster, John B., ed. A History of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, 1902-1926. National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, nd.

Graham, Frank. The New York Giants (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002).

——. The New York Yankees (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002).

Gunther, John. Taken at the Flood: The Story of Albert D. Lasker (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960).

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948).

Kohout, Martin Donell. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2001).

Koppett, Leonard. Koppett’s Concise History of Major League Baseball (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998).

Levitt, Daniel R. Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

——. The Battle that Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012).

Lewis, Franklin. The Cleveland Indians (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1949).

Lieb, Fred. The Baltimore Orioles (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005).

——. Baseball as I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1976).

——. The Baseball Story (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1950).

——. The Boston Red Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1947).

——. Connie Mack (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

——. The Pittsburgh Pirates (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003).

Macht, Norman L. Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

McGarigle, Bob. Baseball’s Great Tragedy: The Story of Carl Mays — Submarine Pitcher (Jericho, New York: Exposition Press, 1972).

Murdock, Eugene. Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1982).

Pietrusza, David. Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1998).

Seymour, Harold and Dorothy. Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford, 1971).

Spink, J.G. Taylor. Judge Landis and 25 Years of Baseball (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1974).

Sullivan, Neil J. The Minors: The Struggles and the Triumph of Baseball’s Poor Relation From 1876 to the Present (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990).

US House of Representatives, Hearings before the Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee of the Judiciary: Organized Baseball (82d Cong., 1st sess., 1952).

US House of Representatives, Report of the Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee of the Judiciary: Organized Baseball (82d Cong., 2d sess., 1952).

Voigt, David Q. American Baseball Volume 1: From Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1983).

Zminda, Don. Double Plays and Double Crosses: The Black Sox and Baseball in 1920 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021).

Notes

1 Letter from Tillinghast Huston to Kenesaw Mountain Landis, November 17, 1920, Kenesaw Mountain Landis papers, Chicago History Museum.