Stefan Wever

Stefan Wever’s “ticket to ride” was a fastball clocked at 95 miles per hour. The 6-foot-8, 245-pound right-hander dominated the minor leagues and became the tallest player in New York Yankees history1 when he took the mound against the eventual American League champions, the Milwaukee Brewers, on September 17, 1982. His dream-come-true quickly turned into his worst nightmare. Wever (pronounced like Weaver) was shelled by Milwaukee’s potent lineup and suffered a shoulder injury that very same night. His attempt to get back to the majors took a long and winding road that was ultimately unsuccessful. Though his big-league career ended after only one game, and he later battled numerous serious health problems, Wever maintained a positive attitude about baseball and life. An avid Beatles fan, his credo was “Take a sad song and make it better,” a lyric from the song “Hey Jude” that he had tattooed on his chest.2

Stefan Wever’s “ticket to ride” was a fastball clocked at 95 miles per hour. The 6-foot-8, 245-pound right-hander dominated the minor leagues and became the tallest player in New York Yankees history1 when he took the mound against the eventual American League champions, the Milwaukee Brewers, on September 17, 1982. His dream-come-true quickly turned into his worst nightmare. Wever (pronounced like Weaver) was shelled by Milwaukee’s potent lineup and suffered a shoulder injury that very same night. His attempt to get back to the majors took a long and winding road that was ultimately unsuccessful. Though his big-league career ended after only one game, and he later battled numerous serious health problems, Wever maintained a positive attitude about baseball and life. An avid Beatles fan, his credo was “Take a sad song and make it better,” a lyric from the song “Hey Jude” that he had tattooed on his chest.2

“It was both the greatest thing, and the worst thing that’s happened to me,” Wever once said of his abbreviated pitching career. “But I don’t think I would ever take it back. I would never wish for it not to have happened.”3

Wever came from a well-educated family. His mother, Dorothy Barnhouse, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1932. Dorothy’s father was a prominent Presbyterian minister who stressed the importance of education; she grew up attending private schools in Canada, Cuba, and France. Dorothy began singing as a toddler and turned her passion for music into a career. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics from Harvard University and became fluent in four languages.4 Later, she studied at the renowned Berliner Hochschule für Musik and received master’s degrees in education and music theory at Harvard and San Francisco State University, respectively. Throughout her life she performed professionally as a mezzo-soprano soloist and taught voice lessons.5 In 1955, Dorothy married Ulrich Wever—an Oxford-educated German who was working on his doctorate at the time.6 After their union, the couple lived in Marburg, Germany, which is where Dorothy gave birth to twins Stefan Matthew and Kirsten on April 22, 1958.

When Stefan was six, his parents divorced, and he moved to Boston with his mother and sister. Ulrich remained in Germany, where he worked in banking and eventually had another son named Pascal. On Stefan’s arrival in America, he took to the national pastime immediately. “I got a baseball in my hand and never put it down,” said Wever, looking back.7 It was during these formative years that he developed a love of the Boston Red Sox.

When Stefan was 12, Dorothy moved him and Kirsten to San Francisco, where Stefan played in the Pony and Joe DiMaggio Leagues and attended Lowell High School. He also played piano and participated in school plays. By his senior year, the lanky Wever had grown to 6-foot-6. He lettered in football and basketball, but baseball was his passion. During his senior season, Wever used “an overpowering fastball and fluttering forkball” to toss a no-hitter against Wilson High and lead the Lowell Cardinals to the city championship game.8 Despite his high school success, he did not receive any baseball scholarship offers.9

In the fall of 1976, Wever matriculated at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he studied English literature and made the Gauchos baseball team as a non-scholarship walk-on player. The highlight of his freshman season was beating the University of Southern California Trojans on a five-hitter in his first collegiate start.10 That summer, he played for a collegiate summer league team called the Humboldt Crabs but was limited by an ankle injury.11 After a successful sophomore showing in the spring of 1978, Wever was named second team All-Conference in the Southern California Baseball Association.12

He then toiled for a collegiate summer team called the Boulder (Colorado) Collegians under Coach Bauldie Moschetti. Established in 1964, the club helped many prospects reach the majors until it folded in 1980.

Wever continued to progress as a junior, winning the Gauchos’ Most Valuable Player award for the 1979 season.13 In the June 1979 amateur draft, the New York Yankees—rivals of his beloved Red Sox—picked the 21-year-old in the sixth round. He was signed by scout Don Lindeberg and assigned to the Class-A Oneonta Yankees of the short-season New York-Pennsylvania League along with 19th-round pick Don Mattingly.14 Wever posted a 6-3 record and 1.77 ERA in 10 games (nine starts), including a 16-strikeout performance against Newark on August 2.15 After a rare subpar outing versus the Geneva (New York) Cubs, Cubs second-round pick Mel Hall came up to Wever in a bar and said, “Weve, how come you don’t throw as hard as people say?” Wever was left speechless. Oneonta and Geneva wound up meeting again in the league championship. “[Hall] was popping off again, so I told him I’d hat-trick him and sure enough, his first three times up he struck out. We won, 3-0, and went on to win the title,” Wever later recounted.16

Wever, who listed his nicknames as “Dream” and “Quiche,” was promoted a rung to the Class-A Fort Lauderdale Yankees of the Florida State League in 1980.17 His manager, Doug Holmquist, said Wever’s “fastball explodes at the plate, and he already has a major league breaking pitch.”18 The tall righty recognized the advantage his height provided. “I worked it out with my physics professor, that if a pitcher releases the ball two feet closer to the plate, it adds seven miles per hour to his fastball,” Wever told the Fort Lauderdale News.19

Wever’s stature could also be a hindrance. He wore size 14 cleats that began to come apart at the seams. Because a new pair had to be custom-made, he had to tape up the old pair until the new ones arrived.20 On June 12, Wever was still wearing the shabby pair of cleats when he got a spike caught on a pickoff attempt and fractured a bone in his foot.21 The injury kept him out of action for a month.22 He finished his abbreviated season with a 7-3 record and 3.64 ERA in 15 starts. Trouble with his breaking ball and changeup command resulted in 54 walks in 94 innings.

The Yankees returned Wever to Fort Lauderdale to begin the 1981 season. On May 24, he pitched 10⅔ shutout innings with 14 strikeouts versus the Tampa Tarpons. The game was eventually suspended after 22 innings and completed the following night, when Fort Lauderdale won in the 23rd frame. After registering a 7-3 record and 2.00 ERA in 12 starts, Wever was promoted to the Double-A Nashville Sounds of the Southern League in June. The Sounds roster was loaded with future big-leaguers, including Mattingly, Willie McGee, Otis Nixon, Buck Showalter (whose playing career actually topped out in Class AAA before he became a successful manager), and Mike Morgan (who’d previously reached The Show as a teenager with Oakland). In Wever’s debut on June 26 versus the Birmingham Barons, he tossed 8⅓ innings of five-hit ball. After his second outing, he developed a sore arm and landed on the disabled list. Wever returned to action three weeks later but was shut down again during the league championship series because of elbow discomfort. In nine starts for the Sounds, he won five of his seven decisions and posted a 2.05 ERA.

Wever spent his 1981-82 offseason in San Francisco working as a bartender and doorman at Pierce Street Annex while taking classes at the University of California, Berkeley to complete his bachelor’s degree. He also squeezed in time for an exercise program to strengthen his arm. By the time he got to spring training, he was throwing without pain. Wever returned to Nashville at the start of the 1982 campaign and was tapped as the Sounds’ opening day starter by manager Johnny Oates. Nashville’s starting rotation looked like an NBA team; besides Wever, who had grown to 6-foot-8, Ben Callahan was 6-foot-7 and Clay Christiansen was 6-foot-5.

Wever thrived under Nashville’s pitching coach—former knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm. Wever’s two-hit shutout versus the Jacksonville Suns on April 30 was his second consecutive complete game. A three-hitter versus Birmingham on May 25 improved his record to 7-1 and lowered his ERA to a league-best 1.79. Wever pitched 98 innings before allowing his first home run.23 “You’d go to the other cities in the league and they’d all ask you if Wever was going to pitch, hoping he wouldn’t,” said Oates.24

By mid-July, Wever had already pitched more innings that he had in any season previously.25 He was voted to the Southern League All-Star team, which played the eventual National League West Division champion Atlanta Braves at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field on July 22. Braves manager Joe Torre rested most of his regulars. Wever threw a scoreless fifth inning and recorded one strikeout. At season’s end, his ledger included a 16-6 record, league-leading 191 strikeouts and 2.78 ERA in 29 starts covering 214 innings. He was voted by league managers and sportswriters as the circuit’s Pitcher of the Year.26 In the best-of-five Southern League finals against Jacksonville, Wever took the ball in Game Three on September 10 and threw a four-hit shutout, striking out 10 in Nashville’s 2-0 win.27 After the Sounds defeated Jacksonville on September 11 to win the league championship series, Wever was soaked with beer and champagne from the team’s celebration when he was called into Oates’ office. “You won’t be seeing any of your friends at the airport when you arrive tomorrow,” said the skipper.28 It wasn’t immediately clear what Oates meant, but Wever soon caught on: he was being called up to the big leagues.

The next morning, Wever flew to New York’s Kennedy Airport and took a taxi to Yankee Stadium. When the cabbie asked where he wanted to be dropped off, Wever took great pleasure in replying, “player’s entrance.”29 The young hurler was awed when he walked into the Yankee clubhouse for the first time. “I was a rookie, so I was expecting the number 92 and a locker in the far corner,” recalled Wever 40 years later.30 Instead, venerable clubhouse attendant Pete Sheehy assigned him number 25 and gave him a locker between superstars Goose Gossage and Dave Winfield. Wever watched his new teammates beat the Brewers that day, 9-8. With three weeks to go in the season the Yankees were in fourth place, 10 games behind first-place Milwaukee.

The Yankees traveled to Baltimore after the game. Wever’s planned roommate, backup catcher Barry Foote, was away from the team because of an illness in the family, so Wever was given his own suite in the team’s luxury hotel. That night, his veteran teammates volunteered him to host a poker game. Throughout the evening and into the morning, Lou Piniella, Bobby Murcer, Oscar Gamble, Winfield, Gossage, and a slew of others came and went. Stefan lost money from a big-league paycheck he had not yet received, but he didn’t care. He was on top of the world.31

Wever did not appear in the Yankees’ five-game series against the second-place Orioles. He watched his team lose all five games. The schedule next sent the Bronx Bombers to Milwaukee, where manager Clyde King tapped Wever to start against the vaunted Brewers at Milwaukee County Stadium in the opener on Friday, September 17. Known as Harvey’s Wallbangers after their manager, Harvey Kuenn, and their power hitting, the Brew Crew boasted a lineup that included three future Hall of Famers—Paul Molitor, Robin Yount, and Ted Simmons—in the first four spots of the batting order. The one member of the foursome that is not in Cooperstown was the ironically named Cecil Cooper, who would end his career as a five-time All-Star and .298 hitter. Things did not much get easier after that. Milwaukee’s fifth- and sixth-place hitters, Ben Oglivie and Gorman Thomas, were both former American League home run champions, and Thomas would tie Reggie Jackson for the home run crown in 1982.

Though the calendar still said summer, the cold, rainy night felt more like autumn. Wever may have been nervous, but it was the Yankees’ defense that was shaky. In the first inning, Molitor greeted Wever with a seeing-eye single to right and scored on Yount’s double into the gap in right-center. Cooper then blooped a fly ball to short center, which Jerry Mumphrey first misjudged, and then let get by him for another double. Before some fans had even bitten into their bratwursts, the Brewers held a 2-0 advantage. Wever induced Simmons to ground to shortstop for what should have been the second out, but Andre Robertson booted it. Oglivie flied to left, and Wever could have been out of the inning with only one run allowed.32 However, the walrus-mustached Thomas stepped to the plate with two on and only one out. On one particular pitch to Thomas, Wever felt a twinge in his shoulder but did not think much of it. “I wasn’t going to come out of my first big-league start, so I just kept pitching, and I don’t think that was a good idea,” reflected Wever.33 Thomas parked the next pitch over the left-field wall for a three-run homer. Wever retired the next two batters without incident but allowed another run in the second and was yanked in the third after running into more trouble. In his 2⅔ innings of work, he allowed six hits, walked three, struck out two, and was charged with eight earned runs for an ERA of 27.00. “A lotta beers after the game,” Wever later joked.34

Wever’s shoulder remained sore after his disastrous debut, so he was prescribed anti-inflammatories and shut down for the remainder of the season. The tall righty was a candidate for the fifth spot in the Yankees’ rotation in the spring of 1983, which is when sportswriter Milton Richman got to know him. “He’s about as wholesome and refreshingly honest as any rookie I can remember coming up to the big leagues in at least the past 20 years,” wrote Richman.35

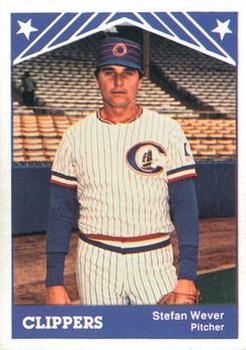

Wever was still hampered by shoulder discomfort during spring training, resulting in his demotion to minor-league camp on March 15. He was then assigned to the Triple-A Columbus Clippers of the International League. The zip on his Wever’s fastball had disappeared; instead of throwing 95, he was topping out at 85.36 He posted a 1-4 record and unsightly 9.78 ERA in seven games (six starts) before landing on the disabled list. Since he could not pitch, he ended up doing color commentary on the Clippers’ broadcasts.37 During the offseason, the Yankees removed Wever from the 40-man roster and outrighted him to Columbus.

Wever pitched only six innings in the spring of 1984. He was throwing without pain but still had not regained his velocity. His shoulder ailment was described as “mysterious” by the Miami Herald, which reported that “trainers describe Wever’s injury as ‘an irregularity at the insertion of the rotator cuff’” but did not believe there was a tear.38

Because Wever was not even pitching up to Triple-A standards, he was sent down to Single-A Fort Lauderdale to start the 1984 season. He was on a major-league contract which paid him $16,000 regardless of where he pitched.39 Wever hoped to start a handful of games at Single A and then make the jump back up to Columbus.40 His shoulder problems lingered, however. He had lost three of four decisions and had a 5.09 ERA in seven games (five starts) when he finally sought an opinion from renowned orthopedist Dr. James Andrews, who diagnosed a torn rotator cuff. Wever underwent arthroscopic surgery that summer. “If I can’t come back from surgery, that’s it for me,” said the 26-year-old hurler. “I’m not going to be one of these guys who hangs around until he’s 30.”41

Wever’s comeback attempt in 1985 was short-lived. He made five appearances in relief for the Double-A Albany-Colonie Yankees of the Eastern League, before deciding to hang up his spikes after a discussion with manager Barry Foote. “I just said, ‘Barry, what are we doing here? It’s not working, is it?’ And he said, ‘No, it’s not.’ So, I took a deep breath and said, ‘That’s it, I’m done,’” recalled Wever.42

In his seven seasons of minor-league ball, Wever compiled a 43-24 record and 3.02 ERA, numbers made all the more impressive because his shoulder caused him to be completely ineffective in his final three professional seasons.

Wever returned home to San Francisco and fell back on his previous offseason job as a bartender. “It was kind of easy, and I was moping around, drinking more than I should have been,” Wever said in 2001. “You know, just partying and not ever really dealing with the underlying emotions of why I was not being productive or ambitious, or why I was staying out late, doing all this stuff.”43 Wever tended bar at Silhouettes in North Beach and eventually worked his way up to manager. It was there that he met his future wife, the former Melinda Foge. The couple wed in 1988 and had a daughter, Megan, five years later.

In 1991, Wever became co-owner of the Horseshoe Tavern on Chestnut Street in San Francisco’s Marina neighborhood, where he became an institution. “Big Guy,” as he was known, stood out literally with his tall frame and figuratively with his outgoing nature. For many years, he played softball on the team that his bar sponsored. Looking back on his baseball career at the time, he exhibited a self-deprecating humor. Wever recalled a time when Wilhelm came to the mound to take him out of a rough outing. “You can’t do that,” Wever said, “I got this batter last time.” Wilhelm responded: “Yeah, but that was THIS INNING!”44

Despite the disappointing end to his career, Wever never fell out of love with baseball. He “de-Yankeefied” himself after his playing career and went back to rooting for the Red Sox.45 Even as his business was thriving, he yearned to get back in the game. “To be quite honest, right now, if I didn’t have to support a wife and a child—if it was just me—I would probably quit this all … and go coach Single-A baseball in Idaho or Iowa for $18,000 a year,” Wever once told the San Francisco Chronicle.46

In the early 2000s, Wever’s marriage fell apart, and he battled alcoholism. During this difficult period, he lost touch with his two passions: music and baseball. “I got multiple DUIs,” he recalled in 2009. “I was out of control, really out of control. I lost my license, wore the ankle bracelet.”47

Wever took his last drink on September 17, 2005.48 Coincidentally, it was the 23-year anniversary of his lone big-league appearance. After he found sobriety, Wever rekindled his love of music, cutting a full-length album called “The Gardener” on which he sang and played piano.49 He also returned to the national pastime, volunteering as a pitching coach with the freshman baseball team at Redwood High School in Marin County. When the varsity coach retired in 2009, he took over the program and led the team to the playoffs. “Wever’s favorite part of coaching has been his ability to not only teach about baseball skills, but also teach character, and do it from the perspective of someone who lost track of both for some time,” wrote the Marin Independent Journal.50

As Wever was completing his first year as a varsity coach, he was diagnosed with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, a rare and aggressive cancer. In spite of another setback, he remained upbeat. “My motto is: ‘It’s not how you fall down. It’s how you get up,” he said at the time.51 In fact, the lyrics in his song “When I Fall Down” include the chorus, “I fall down seven times, and so I get up eight.”52

The cancer diagnosis was not Wever’s first health issue. Two years earlier, he had open heart surgery to replace a faulty heart valve. He jokingly told the surgeon to work around his Beatles-inspired chest tattoo, which included the inspiring line from “Hey Jude.” Wever’s love of the Fab Four dated back to 1964, when his parents took him to see “A Hard Day’s Night” at a German movie theatre.53 He collected Beatles art and memorabilia and saw Paul McCartney in concert countless times. Wever’s favorite song was “Let It Be”—lyrics from which were inked on his back.54

He began chemotherapy in the spring of 2009 and then underwent a bone marrow transplant. A year later, he developed a heart valve infection and suffered a stroke.55 Despite his string of health problems, Wever “remained optimistic and kept his sense of humor throughout.”56

Wever’s medical issues forced him to give up his varsity coaching position. He left a lasting impression on his players, however, as evidenced by the entire team visiting him in the hospital during his illness. In 2013, Wever returned to baseball as bench coach for the San Rafael Pacifics, an independent minor-league team.

Despite dealing with his own struggles, Stefan found time to help those who were less fortunate, spending years volunteering in the dining room at St. Anthony’s, a San Francisco organization dedicated to helping people experiencing homelessness.

In 2019, Wever moved to Portland, Oregon, to be closer to his daughter, though he still maintained ownership of his business in San Francisco. Wever died suddenly of natural causes on December 27, 2022, in Portland. He was 64.

Stefan Wever had a recurrent dream long after his baseball career ended. “I’m on a field, but it’s more like a cow pasture,” he described. “Don Mattingly’s there. Buck Showalter’s also there. All my teammates are there. And I’m there, trying to get back into the major leagues. But I never quite make it to the field.”57

Acknowledgments

The author had the privilege of interviewing Stefan Wever on December 1, 2022, just a few weeks before his sudden passing. Many thanks to Megan Wever for providing additional information over the phone on June 10, 2023.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Notes

1 Wever’s status as tallest Yankee was tied by 6-foot-8 Lee Guetterman in 1988. At 6-foot-10, Randy Johnson obtained that distinction when he joined the Yankees in 2005. Johnson was tied in 2011 by Andrew Brackman.

2 Gwen Knapp, “When a Good Coach Gets Some Bad News,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 24, 2009: C1.

3 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 17, 2001: D1.

4 Dorothy Barnhouse Obituary, San Francisco Chronicle, June 28, 2019: 26.

5 Barnhouse Obituary.

6 “Activities in Phila., Suburbs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 1955: 14.

7 Stefan Wever telephone interview with the author, December 1, 2022 (“Wever interview”).

8 “Wever Fashions No-Hitter for Lowell,” San Francisco Examiner, March 18, 1976: 55.

9 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner.”

10 Stefan Wever, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, January 5, 1980 (“Wever Publicity Questionnaire”). “Gauchos Top USC Twice,” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1977: 42.

11 “Crabs Will Vie Tonight,” Times-Standard (Eureka, California), June 29. 1977: 18.

12 “College Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1978: 63. Future big-league star Tim Wallach of California State Fullerton received first team honors and was voted the Association’s MVP.

13 Wever Publicity Questionnaire.

14 Ron Gardenhire, Harold Reynolds, and Bill Doran were other notable sixth-round selections in 1979.

15 “Wever Whiffs 16 Batters, O-Yankees Earn a Split,” Press and Sun Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), August 3, 1979: 20.

16 Wever Publicity Questionnaire.

17 Wever Publicity Questionnaire.

18 Steve Hummer, “New Barn Full of Baby Yankees Hatches Tonight,” Fort Lauderdale News, April 11, 1980: 20.

19 Steve Hummer, “New Barn Full of Baby Yankees Hatches Tonight.”

20 Ray Boetel, “Size 14s … Feet, Don’t Fail Me Now,” Fort Lauderdale News, June 13, 1980: 17.

21 Ray Boetel, “Size 14s … Feet, Don’t Fail Me Now.”

22 Randy Phillips, “Dave Sax Leads Vero Win,” Press-Journal (Vero Beach, FL), July 15, 1980: 14.

23 Tom Squires, “Tough Luck: Wever Falls on Home Run,” (Nashville) Tennessean, June 5, 1982: 13.

24 Milton Richman, “Stefan Wever Biggest N.Y. Yankee,” Brattleboro Reformer (Brattleboro, VT), March 4, 1983: 10.

25 “Wever Hurls Sounds to 3-1 Win Over Jays,” Morning Press (Murfreesboro, TN), July 19, 1982: 9.

26 “Wever, Sounds Score 4-2 Win Over Lookouts,” Tennessean, August 30, 1982: 35.

27 Mike Morrow, “Sounds Top Suns,” Tennessean, September 11, 1982: 13.

28 Tom Dinard, “Sunlight for a Moonlight Man,” The Post Game, January 17, 2012, https://www.thepostgame.com/features/201201/sunlight-moonlight-man, accessed June 8, 2023.

29 Wever interview.

30 Wever interview.

31 Tom Dinard, “Sunlight for a Moonlight Man.”

32 “Brewers eliminate Yanks from race,” Daily News (New York), September 18, 1982: 184.

33 Wever interview.

34 Milton Richman, “Stefan Wever Biggest N.Y. Yankee.”

35 Milton Richman, “Stefan Wever Biggest N.Y. Yankee.”

36 Wever interview.

37 Bernard McCormick, “Majoring in the Minors,” Fort Lauderdale News, August 5, 1984: 400.

38 Greg Cote, “Ex-phenom Wever Starting All Over,” Miami Herald, April 8, 1984: 725.

39 Bernard McCormick, “Majoring in the Minors.”

40 Greg Cote, “Ex-phenom Wever Starting All Over.”

41 Bernard McCormick, “Majoring in the Minors.”

42 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner.”

43 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner.”

44 “Tale of a Big-League Chaser,” Modesto Bee, August 9, 1991: 26.

45 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner.”

46 Chris LaMarr, “One-Time Big-Leaguer Now Longtime Bar Owner.”

47 Gwen Knapp, “When a Good Coach Gets Some Bad News.”

48 Vincent Tannura, “Wever’s Dream: Former Phenom with Major League Future Finds Bliss as Coach of Redwood High School,” Marin Independent Journal, May 10, 2009, https://www.marinij.com/2009/05/10/wevers-dream-former-phenom-with-major-league-future-finds-bliss-as-coach-of-redwood-high-baseball-team/, accessed June 7, 2023.

49 Stefan Wever Obituary, San Francisco Chronicle, April 4, 2023: 4.

50 Vincent Tannura, “Wever’s Dream: Former Phenom with Major League Future Finds Bliss as Coach of Redwood High School.”

51 Gwen Knapp, “When a Good Coach Gets Some Bad News.”

52 Wever’s album can be found here: https://www.reverbnation.com/stefanwever/songs.

53 Tom Dinard, “Sunlight for a Moonlight Man.”

54 Gwen Knapp, “When a Good Coach Gets Some Bad News.”

55 Tom Dinard, “Sunlight for a Moonlight Man.”

56 Stefan Wever Obituary, San Francisco Chronicle, April 4, 2023: 4.

57 Ed Attanasio, “Stefan Wever’s Promising MLB Career Lasted Just 2-2/3 Innings,” Marina Times, February 2011, http://www.marinatimes.com/feb11/sports-sportscorner.html, accessed June 8, 2023.

Full Name

Stefan Matthew Wever

Born

April 22, 1958 at Marburg, (Germany)

Died

December 27, 2022 at Portland, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.