Jack Clark

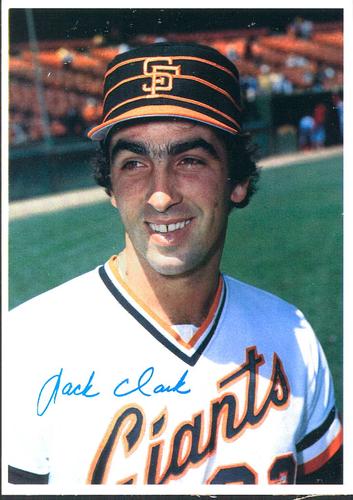

From the late 1970s through the early 1990s, few players were as feared with the bat or possessed the brashness of Jack Clark. Twice he powered teams to the World Series. Four times he played in the All-Star Game. His prowess at the plate moved his manager to call him “the greatest fastball hitter of his era.”1

From the late 1970s through the early 1990s, few players were as feared with the bat or possessed the brashness of Jack Clark. Twice he powered teams to the World Series. Four times he played in the All-Star Game. His prowess at the plate moved his manager to call him “the greatest fastball hitter of his era.”1

Jack Anthony Clark was born November 10, 1955, in New Brighton, Pennsylvania, an industrial town 28 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. Clark’s father, Ralph, worked in the coal industry. In 1957, Ralph Clark, his wife Jennie and their two children, Larraine and Jack moved to Covina, California, a working-class community of 20,000, 22 miles east of Los Angeles, where Ralph Clark went to work in a paint factory.

Once Clark enrolled at Gladstone High School, his athletic endeavors traveled a series of peaks and valleys. As a freshman he quit baseball. “I had some bad experiences with my baseball coaches,”2 Clark explained. A friend, Greg Johnston, convinced Clark to rejoin the team for his sophomore season. Jack would miss the bulk of his team’s games after he suffered a broken wrist. By the midway point of Clark’s junior season, his exceptional baseball talent began to blossom. In April 1972, Clark pitched a no-hitter and was featured as a high school athlete of the week in the Los Angeles Times.

“Jack has great promise,” his coach Stu Reeder said. “He’s the best 11th grade pitcher I’ve seen all year.”3 With Clark pitching 3 2/3 innings of one-hit relief while striking out seven, Gladstone High knocked off the defending champions, Sonora High, to win the CIF 2A Championship.

A new assistant baseball coach at Gladstone, Mike Ocon, invited San Francisco Giants scout, George Genovese, to speak at the team banquet. During the evening Ocon urged Genovese to come out and watch Clark the following spring.

In the spring of Clark’s senior season, scouts were commonplace in the stands at Gladstone High baseball games. Clark had become the undisputed standout of the team. By late April, he had an 8-2 record with five shutouts and was batting .500. During the final weeks of the season, Ocon continued to pester Genovese to come out and watch Clark play. Once the scout did, he was not disappointed.

“What I saw was just another high school pitcher, a kid with a strong arm but not much of an idea what to do with it,”4 Genovese said. Clark didn’t fare well in the game and was soon moved to third base. When that happened, the other scouts got up and left, leaving Genovese as the only scout still in the stands. Once Clark came to bat an inning later, he turned on a fastball and hammered the pitch over the outfield fence for a long home run. “I liked his swing. His bat speed and power opened my eyes,”5 Genovese said. After the game Clark simmered with anger. “I asked Jack what he was so mad about. He said, ‘I saw those scouts walk out. Everybody’s talking up [Gary] Roenicke [at a rival high school]. Well, he can’t carry my jock! I’ll prove it if somebody will give me a chance.’”6 The next morning Genovese phoned his boss to recommend the Giants take Clark in the coming draft.

On June 5, 1973, the San Francisco Giants made Jack Clark their 13th-round selection in the Major League Baseball draft. Clark agreed to a $10,000 bonus but had one request. He wanted to play in an American Legion All-Star doubleheader against West Covina. It was Clark’s goal to show that he was better than Roenicke, who had been chosen in the first round by the Montreal Expos. That night Clark belted two long home runs. After the game Genovese handed the player a plane ticket to join the Giants’ rookie club at Great Falls, Montana.

Great Falls manager Art Mazmanian took a keen interest in Clark. “My daughter was the scorekeeper at Walnut High. They played Gladstone. For two years she had been telling me about Jack Clark,”7 the manager said. On instructions from San Francisco, Mazmanian added Clark to his pitching rotation. After Clark pitched in five games, however, the manager faced a predicament. “I brought Jack into my office, and I told him he wasn’t going to pitch anymore. He wasn’t happy, but I said, ‘You’re too good of a hitter. Every major-league team has just one .300 hitter. You have a chance to be a .300 hitter in the big leagues.’”8

Almost immediately, Clark went on a hitting tear. “He hit in 17 consecutive games,”9 Mazmanian said. “They got him out, then he hit in 13 more.”10 Six weeks after the position change, Clark was leading the Pioneer League in home runs and runs batted in. He finished the season second in home runs with nine, second in runs batted in with 54, and fourth in batting average at .321. It earned Clark a spot on the league All-Star team. “And he was only 17,”11 Mazmanian said.

In October, the Giants summoned Clark to Phoenix to participate in their fall instructional program. “You could see right away that he had tremendous tools,” recalled John Van Ornum, one of the Giants’ coaches. “His bat was something special.”12 The decision was made to have Clark bypass the Midwest League and spend 1974 with the Giants’ Class A farm club at Fresno in the California League.

On a club that boasted eight future major leaguers, Jack Clark blossomed into a star. Throughout the summer he chased the league batting title before finishing third with a .315 average. Clark led the league with 117 runs batted in, 19 more than the runner-up. Clark was named California League Rookie of the Year.

In the summer of 1975 Clark hit 23 home runs, drove in 77 runs, and batted .303 for the Lafayette Drillers of the Class AA Texas League. After the season the 19-year-old Clark received a September call-up to join the San Francisco Giants. Gary Matthews met Clark at the airport and drove him to Candlestick Park. Clark made his major-league debut on September 12. He walked in an eighth-inning pinch hit appearance against the Cincinnati Reds and veteran left-hander, Fred Norman. Three nights later he got his first major-league hit, a single to left field off Atlanta’s Preston Hanna. In San Francisco’s final game of the season, Clark gave fans and Giants management a glimpse of the future. Starting in right field, Clark lofted a first-inning sacrifice fly that plated the game’s first run against San Diego’s 20-game winner, Randy Jones,. In the fifth Clark stroked a single to left and two innings later a hot line-drive single to right.

Labor strife cost Clark a chance to open the 1976 season in the big leagues. Owners locked players out of spring training camps for 17 days. An abbreviated spring training led many managers, like the Giants’ newly hired skipper, Bill Rigney, to go with veteran players rather than unproven rookies. Brashness that would become synonymous with Clark was brought to the surface by the lost opportunity. “I know I can play in this league,” the 20-year-old said. “In fact, I think I can do more things than [Giants right fielder] Bobby Murcer.”13

Clark got off to a strong start with the Giants’ top farm club, Phoenix in the AAA Pacific Coast League. He was now a full-time right fielder. On June 15 he was hitting .320 when a freak accident sidelined him. During a game in Albuquerque, Clark was sprinting for home when Kevin Pasley, the Albuquerque catcher, flung his mask aside to prepare to take a throw. The heavy metal mask struck Clark in the face. “I think I fell like a rock,” Clark said. “I was pretty stunned.”14 It required 28 stitches to close a gash to the player’s lip. By August, Clark was fully recovered and resumed his pursuit of the Pacific Coast League batting title. “I’ve been in this league for four years, and he’s the best hitter I’ve seen,”15 said Albuquerque manager Stan Wasiak. Success made Clark antsy. “I don’t think I have anything left to prove in the minor leagues,”16 he said.

When major league rosters were expanded in September, Clark was called up to San Francisco once again. For the remainder of the 1976 season, Clark started every Giants game. He had seven two-hit games, and hit his first big league home run off Cincinnati’s Jack Billingham on September 11. The next night he drove in three runs against the Reds with a double and a triple.

Following the 1976 season, the Giants hired their third manager in as many years, Joe Altobelli. Unlike his predecessors, Altobelli was from outside the organization and didn’t know the Giants’ personnel. He knew that Clark had a prolific minor league résumé and early in the season found out that he carried unbridled brashness, too.

“I don’t think I have any weaknesses,” Clark told a San Francisco writer. “Some people have God’s gift to play, and I think I have it.”17 Altobelli and Clark would soon clash. The manager utilized a platoon system for the 1977 season. “Something I had to do to find out about the club,”18 Altobelli explained. The outfielder sulked. The manager didn’t like it. Frequent chats between the two brought about an understanding and more consistent playing time.

When the 1978 season rolled around, the 22-year-old Clark tore through spring training with a .367 batting average. In June he erupted into one of the best hitters in baseball. Between June 30 and July 26, Clark hit in a team-record 26 consecutive games. The streak propelled his batting average to .322, best in the National League. During his hitting streak, Clark also went on a power surge, hitting home runs in five successive games. His success brought N.L. Player of the Week recognition. In July Clark was selected to play in the All-Star Game. He finished the season with a .306 batting average, 25 home runs, and 98 runs batted in, ranking in the top ten in each category. Postseason accolades included votes for Most Valuable Player — he finished fifth — and praise from his manager. “I can’t imagine a player being so good, so young. You have to go back to when Mickey] Mantle broke in,”19 Altobelli said.

Clark’s ascension continued in 1979. He earned his second All-Star Game selection, finished second among the Giants in home runs, 26, and runs batted in, 86. Away from the field, marriage to Tamara Kohl added family responsibility that would grow a year later after the birth of the couple’s first child, a daughter, Danika.

In 1980 the team’s clubhouse became a powder keg. A parade of players demanded trades and vented displeasure with their manager, Dave Bristol. In mid-August, Clark had a .289 batting average and 22 home runs. Then his starry run ended. He was hit in the left hand by a pitch and suffered a broken bone. When Clark came back in September, he joined the stormy chorus. During a team meeting, Clark blasted the manager. “There are players who are jaking on this team, and Bristol doesn’t do a thing about it,” Clark said. “He’s lost control.”20

Following the season, Bristol was fired. Frank Robinson became Clark’s fifth big-league manager. Clark’s penchant for destruction of opposing pitchers continued. So too did his practice of criticizing his manager. On August 27, 1981, against Pittsburgh, Clark blasted a game-winning home run in the 13th inning. It vaulted the Giants into a first-place tie in the second half of a split season created by a labor strike. Once he completed a postgame radio show, Clark was told that Robinson had chewed the team out. The slugger shot back. “He criticizes us, but his managing hasn’t been all that great,” Clark vented. “I think he’s more concerned about himself looking good.”21

Because of the players’ strike, the season was shortened by 38 percent. Clark clouted 17 home runs, drove in 53 runs, and batted .268. Both his batting and vocal prowess prompted teammate Vida Blue to tag the volatile slugger “Jack the Ripper.”

The acquisition of veteran Joe Morgan aided both the team’s success on the field in 1982 and Clark’s maturity. The teammates had lockers next to each other and talked baseball frequently. Morgan’s lessons hit home.

“I just told Jack that it takes more than hitting home runs to be a superstar, that it takes a certain responsibility to work a little harder and do a lot of little extra things,”22 Morgan said. Clark took the lessons to heart. His best season to date took the Giants into the final weekend of the 1982 campaign trailing first place Atlanta by one game. Losses in two of the team’s final three games relegated San Francisco to a third-place finish. Clark led the Giants with 27 home runs and 103 runs batted in and hit .274 for the season. He finished seventh in voting for the Most Valuable Player Award.

The 1983 Giants plummeted in the standings. By his own admission, Clark spent much of the season in a rut. “I came to camp feeling down because of the Joe Morgan deal,” he explained of the trade that sent his mentor to Philadelphia. “I never had a player influence me like he did.”23 Things weren’t much better a year later. Clark missed part of spring training with a hand ailment. In June he suffered a knee injury that required surgery and ended his season. Late in the season Robinson was fired. Talk swirled that Clark was through as a Giant as well. “We are not trying to move Jack Clark,”24 the Giants’ general manager, Tom Haller, said. Three months later, however, the Giants did — to St. Louis.

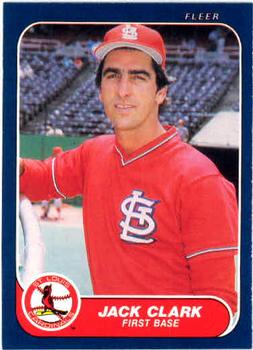

The Giants sent Clark to the Cardinals for four players. “I think Jack Clark puts us in a situation of being a definite contender,”25 said Whitey Herzog, the Cardinals’ manager. Clark flourished in his new home. Playing first base, he helped fuel the Cardinals to a 101-win season and a division title. He led the team in home runs with 22 and was second in runs batted in with 87. He was selected to play in his third All-Star Game. After the season Clark received the Silver Slugger Award as the best-hitting first baseman in the National League.

The Giants sent Clark to the Cardinals for four players. “I think Jack Clark puts us in a situation of being a definite contender,”25 said Whitey Herzog, the Cardinals’ manager. Clark flourished in his new home. Playing first base, he helped fuel the Cardinals to a 101-win season and a division title. He led the team in home runs with 22 and was second in runs batted in with 87. He was selected to play in his third All-Star Game. After the season Clark received the Silver Slugger Award as the best-hitting first baseman in the National League.

The success sent him into the postseason for the first time, and to the signature moment of his big-league career. It came on October 16, 1985, in the top of the ninth inning in the National League Championship before a sold-out Dodger Stadium. Clark faced Dodgers’ relief ace Tom Niedenfuer. Though leading in the best-of-seven series, 3 to 2, St. Louis trailed the Dodgers, 5-4. The Cardinals had two runners on. Clark had been nursing pulled rib muscles and hadn’t hit a home run in over three weeks. Niedenfuer’s first pitch was a fastball, intended for the outside corner. The pitch strayed toward the middle of the plate, and Clark whacked it deep into the left-field stands. The three-run home run propelled the Cardinals to a 7–5 win and into the World Series.

An epic meltdown resulted in the loss of the Series to the Kansas City Royals. With a 3-wins-to-2 lead over the Royals and leading Game Six, 1–0, in the ninth, two controversial plays that involved Clark led to a crushing defeat. The leadoff hitter, Jorge Orta, hit a ball sharply to Clark. He shoveled the ball to Todd Worrell, who was covering first base. The first base umpire, Don Denkinger, called Orta safe. Television replays showed that Orta should have been called out.

The next batter, Steve Balboni, hit a pop fly in foul territory near the first base dugout. To the dismay of Cardinals fans, the ball fell untouched between Clark and catcher Darrell Porter. Balboni would later reach base. Later in the inning Dane Iorg singled home two runs to give Kansas City a 2-1 win and force Game Seven. Columnists criticized Clark for not catching the foul pop; however, Porter acknowledged that he had called his first baseman off the ball.

The next night Kansas City walloped a frustrated and spent St. Louis team, 11–0, to capture the World Series.

Hopes of a repeat trip to the Series took a serious jolt in mid-June of 1986. On a headfirst slide into third base during a game in Pittsburgh, Clark suffered a torn ligament in his right thumb. The injury required surgery. His hand was placed in a cast for six weeks and he missed the remainder of the season.

Clark rebounded in 1987 to enjoy the biggest season of his career. He spent much of the season battling for the N.L. home-run and RBI lead. In July fans selected Clark to start at first base in the All-Star Game. On August 9 he eclipsed the 30-home-run mark for the first time — the first Cardinal to do so in 16 years. Clark’s play pushed the Cardinals to as much as a 10-game division lead. “No one man is going to win the pennant for us,” said Cardinals pitcher John Tudor, “with the exception of Jack Clark.”26

On September 9, Clark sprained his right ankle. He played little over the final month. Still, he hit 35 home runs, drove in 106 runs, and hit .286. The Cardinals won their division and were matched with the San Francisco Giants in the National League Championship Series. In his only time at bat against his former team, he struck out. Still, the Cardinals won the series and advanced to their second World Series in three years. Clark’s ankle was still balky. He could only watch as the Cardinals fell to the Minnesota Twins.

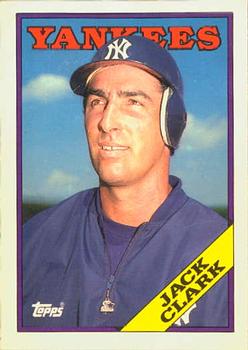

During the postseason Clark received his second Silver Slugger Award. He finished third in MVP balloting behind Ozzie Smith and the winner, Andre Dawson. Joy at accolades was drowned by an inability to successfully negotiate a new contract with the Cardinals. The slugger instead accepted a two-year offer for $3 million and an additional $1 million in incentive bonuses from George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees. Whitey Herzog was stunned. The Cardinals’ manager said, “Without Jack, we’ll be lucky to play .500 ball.”27

After playing in the field his entire career, Clark was made the Yankees designated hitter for 1988. By late June, he was second on the club in home runs and third in RBIs. The Yankees led the American League East by two games. When they were swept by second-place Detroit and knocked out of first place, on June 22 George Steinbrenner reacted by firing Billy Martin, replacing him with Lou Piniella. A month later the team acquired a new designated hitter, Ken Phelps, in a trade with Seattle. When Clark entered the dugout before a game on July 26 and saw a lineup card that had him playing left field for the first time in 12 years, he bellowed in front of sportswriters, “What kind of —- is this?28

After playing in the field his entire career, Clark was made the Yankees designated hitter for 1988. By late June, he was second on the club in home runs and third in RBIs. The Yankees led the American League East by two games. When they were swept by second-place Detroit and knocked out of first place, on June 22 George Steinbrenner reacted by firing Billy Martin, replacing him with Lou Piniella. A month later the team acquired a new designated hitter, Ken Phelps, in a trade with Seattle. When Clark entered the dugout before a game on July 26 and saw a lineup card that had him playing left field for the first time in 12 years, he bellowed in front of sportswriters, “What kind of —- is this?28

Clark suggested he be traded. Three weeks after the season he got his wish — traded to the San Diego Padres. A notoriously slow starter, Clark struggled more than usual early in the 1989 season. Through the first two months, the once-feared slugger was batting .193. Padres’ manager Jack McKeon stuck with the veteran. “Jack was trying to do too much, and part of the reason was he wasn’t getting many pitches to hit,”29 said McKeon. In mid-July Clark shortened his swing, squared his shoulders, and moved up in the batter’s box. The change worked. He hit safely in 14 consecutive games and finished the season with 26 home runs and 94 runs batted in, which led the team.

Clark’s second season with the Padres was riddled with injuries and controversy. In early May he was sent to the disabled list by a low back injury. Clark no sooner returned to the team when he re-aggravated the injury while pulling on a sock. On May 25, while shagging balls in the outfield before a game, he was struck on the cheek by an errant throw, suffering a broken bone that required surgery.

Traveling with the team though injured, Clark instigated an outburst that fractured the San Diego Padres. For weeks a handful of players had grumbled about the team’s star player, four-time batting champion Tony Gwynn. On May 24, before a game in Shea Stadium in New York, McKeon called a clubhouse meeting to address the matter. The meeting was barely underway when Clark stood and flung a can of root beer. It landed between the legs of pitcher Mark Grant and exploded. So too did Clark. “You’re the problem on this team,” he shouted at Gwynn. “You’re a selfish son of a bitch!”30 Gwynn leaped from a chair, and the pair screamed at each other nose to nose. For 50 minutes, fury raged. Reporters could hear muffled hollering from beyond the clubhouse doors. Clark accused Gwynn of being more concerned with his statistics than winning, of bunting to pad his batting average instead of trying to drive the ball and drive runners home. Mike Pagliarulo and Garry Templeton were seen to agree. Clark later insisted his words were meant as constructive criticism, but that Gwynn had taken them personally.

Amid the turmoil and despite missing five weeks of the season to his injuries, Clark managed to clout 25 home runs. But San Diego chose not to re-sign the slugger. Clark was not unemployed long. The Boston Red Sox swooped in with an offer of $8.7 million over three years. “We got ourselves a big bopper,”31 Boston manager Joe Morgan declared.

Clark’s 17th big-league campaign produced his second-highest home-run total, 28. His 87 runs batted in led the Red Sox. Boston finished second behind Toronto in the American League’s Eastern Division.

Through much of the 1992 season, Jack Clark was a distracted man. On August 8 newspapers revealed the reason: Clark had filed for bankruptcy. The media trumpeted stories of Clark’s fleet of 18 expensive cars, 17 of which he was still paying for, a drag-racing venture that had lost $1 million, two homes including one that was worth $2.4 million, credit card debts that ranged from $20,000 to $55,000, a $400,000 tax bill, and outstanding fees to his agents of more than $200,000. In all, Clark faced 50 claims totaling $7.5 million.

The following spring Clark reported to spring training overweight and out of shape. Workouts were paused while he made several cross-country trips for court proceedings. Finally, he requested and was granted his release from the Red Sox. A month later he signed with Montreal. “He can be a clutch hitter who can give us some big RBIs,”32 said Felipe Alou, the Expos’ manager. However, Clark’s lack of conditioning was a problem. While working out in Florida, he received distressing phone calls from his wife. She and their four children were being evicted from the family’s Southern California condo. Power to the family’s home had been turned off. Frustrated, concerned for his wife and children, Clark retired from baseball.

Months after his retirement, Clark received a financial lifeline. In November 1990 two arbitrators ruled that baseball team owners had colluded to drive down the salaries of free agents in 1985, 1986, and 1987. One of the players most adversely affected was Jack Clark. After settlement negotiations, Clark was awarded $4.4 million. Between the award, liquidation of his multimillion-dollar home, car collection, and other assets, Clark was able to pay off every claim made through the court. “Which is basically unheard of in bankruptcy cases,” said Laurel Zaeske, the court-appointed lawyer. “This is a success story for everyone.”33

In 1999 Clark was hired to manage a club in an Independent League, the River City Rascals. Following the season, he joined the Los Angeles Dodgers as a hitting instructor in their minor-league system. In 2001, on the recommendation of Tommy Lasorda, Clark was promoted to major-league hitting coach.

On the day before the 2003 season opener, Clark was involved in a near-fatal traffic accident. He was riding his motorcycle to a workout in Phoenix when a minivan made an unsafe lane change and clipped a car. The car spun out of control and into Clark. When Clark woke up, he was in the hospital with a concussion, eight broken ribs, and severe cuts to his face and head. It was almost two months before he received clearance to resume coaching duties. Throughout the summer the Dodgers struggled. By August they were last in the National League in batting average and runs scored. On August 4 Clark was fired.

Over the next four years he resumed coaching Independent League clubs. The assignments brought a move to the state of Texas, where he was also able to relish time with his four children, Danika, Rebekah, Anthony, and Erika.

In 2009 Clark moved into broadcasting. He spent two seasons as a pre- and postgame show analyst covering St. Louis Cardinals games. The former All-Star also dabbled in sports talk radio. In 2013 he again made headlines; on a radio talk show he accused Los Angeles Angels’ slugger Albert Pujols of having used performance-enhancing drugs. Pujols angrily denied the accusation. He filed a lawsuit against Clark, who retracted his comment and apologized. Pujols then dropped the legal action.

Jack Clark’s baseball legacy will no doubt involve his rare skills—his 340 home runs made him 47th on the list of baseball’s best home-run hitters when he retired. His was a power prowess that injected such fear into pitchers that they walked Clark 1,262 times—a total exceeded by only 27 players when he retired. Herzog said of Clark, “One hell of a hitter; he puts the fear of God in you when he comes up to bat. He’s a good guy to have on your club, in your clubhouse.”34

Last revised: October 8, 2020

Acknowledgments

Information for this biography has been compiled from conversations with Mike Ocon, John Van Ornum, Art Mazmanian, and George Genovese. It was reviewed by Andrew Sharp and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

Resources utilized include the Los Angeles Times, The Sporting News, A Scout’s Report—My 70 Years in Baseball, Bob Chandler’s Tales from the San Diego Padres, and Orange Coast Magazine. Statistical information is from The Sporting News and Baseball Reference. Box score information is from Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Jonathan Pitts, Whitey Herzog, You’re Missin’ a Great Game: From Casey to Ozzie, the Magic of Baseball and How to Get it Back (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1999): 122.

2 Nick Peters, “Clark Complete, Confident—and Only 22,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1978. 3.

3 Don Snyder, “Top Prep Performers: Baseball Players, Swimmer Show Great Abilities in Tough Contests,” The Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1972.

4 George Genovese, A Scout’s Report, My 70 Years in Baseball (McFarland and Company, Inc., Jefferson, N.C., 2015): 172.

5 Genovese, A Scout’s Report, 172.

6 Genovese, A Scout’s Report, 172.

7 Art Mazmanian, telephone interview, July 27, 2017.

8 Mazmanian, interview, 2017.

9 Mazmanian, interview, 2017.

10 Mazmanian, interview, 2017.

11 Mazmanian, interview, 2017.

12 John Van Ornum, telephone interview, July 25, 2017.

13 Art Spander, “Short Spring Gives an Edge to Giants Old Hands,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1976. 15.

14 Carlos Salazar, “Thrown Catcher’s Mask Injures Giants Clark,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1976. 33.

15 Staff, “Coast Chronicle”, The Sporting News, September 4, 1976. 28.

16 Bob Eger, “Alexander, Clark Continue Giant Stepping at Phoenix,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1976. 31.

17 Spander, “Giants Junk Platooning, Rookie Clark Promoted,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1977. 5.

18 Nick Peters, “Better Attitude Boosts Clark’s Play as Giant,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1978. 10.

19 Peters, “Better Attitude Boosts Clark’s Play as Giant,” 10.

20 Peters, “Clark’s Blast Makes Bristol Bristle,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1980. 29.

21 Peters, “Clark Explosion —Giant Air,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1981. 33.

22 Peters, “Clark is Accepting Leadership Role,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1981. 35.

23 Peters, “Jack the Ripper Has Mellowed,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1984. 18.

24 Jim Street, “Giants Don’t Plan to Trade Clark,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1984. 52.

25 Rick Hummel, “Herzog: We Can Do It With Clark,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1985. 34.

26 Staff, “N.L. East Notes,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1987. 23.

27 Rick Hummel, “Herzog: We’ll Be Lucky to Play .500,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1988. 43.

28 Bill Madden, “Piniella Takes on Roster Monster,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1988. 20.

29 Dave Nightengale, “Has Trader Jack Succeeded in Making Padres Holy Terror?” The Sporting News, April 9, 1990. 8.

30 Bob Chandler, “Bob Chandler’s Tales from the San Diego Padres,” Sports Publishing, LLC., 2006. 115.

31 “Red Sox Give Clark $8.7 Million as DH,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1990. 35.

32 Jeff Blair, “Alou Expects Expos to Tend to Business,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1993. S-19.

33 Strahinich, “The Resurrection of Jack the Ripper,” Orange Coast Magazine, February 1995. 53.

34 Nightengale, “Herzog’s Trump Card,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1988. 11.

Full Name

Jack Anthony Clark

Born

November 10, 1955 at New Brighton, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.