Tom House

“I think I was put on this earth to be a coach.”1

“I think I was put on this earth to be a coach.”1

“Have you ever had an itch you can’t scratch? Athletes have one for life, a ‘jock’s itch’ that a ton of Tinactin won’t cure.”2 So writes Tom House, former left-handed pitcher who, after he retired from baseball, went on to pursue graduate studies. He ultimately obtained a Ph.D. in sports psychology, and launched a new career to offer instruction to aspiring athletes in a number of sports.

House spent eight seasons in baseball’s major leagues during the 1970s, compiling a 29-23 record for the Atlanta Braves, Boston Red Sox, and Seattle Mariners.

It was his in post-playing career, however, where House made his mark, as a sports psychologist. He had advised not only baseball pitchers but also athletes such as football quarterbacks Drew Brees and Tom Brady. Brady once stated, “[House] says when you pass a certain age you really got to learn to re-learn … A lot of it’s re-learning different things that maybe you’ve done or have become habits that you’ve done thousands and thousands of times, (and) that you really need to train yourself a different way to improve certain aspects of your mechanics.”3

House has kept so busy – as coach and consultant, author and co-author, co-founder and CEO of both the National Pitching Association and 3DQB, and developer of a new app called Mustard – that at the time of an August 2021 interview he was preparing to go on vacation for the first time in his life.4

Thomas Ross House was born in Seattle, Washington on April 29, 1947. His father, Thomas E. House, was a civil engineer. The elder House worked for American Pipe and Construction Company, starting in Portland, then Seattle. The family, including brother Bill (a younger sister, Peggy, died of cancer at age 4), moved south to La Puente in the Los Angeles area when Tom was a freshman in high school. Tom’s mother Ruth was, he says, an Iowa farm girl/mother/housewife.

“My dad was the ultimate nerd. He appreciated sports, but I came home one day and said, ‘Dad, I threw a no-hitter.’ He said, ‘Great. What’s a no-hitter?’ And then he asked, ‘How did you do it?’ He lived to be 100 and he still didn’t quite understand what I did for a living as a coach – but that’s OK.

“My mom would basically say, ‘That’s great. Did you get an A in English today?’ While my parents were very supportive of sports, my dad wanted to know ‘Why?’ and my mom had a rule: ‘No A, no play.’ She made my brother and I realize the value of education. She would say. ‘Sports will go away, but your education never will.’

“I was blessed to have them as parents.”

The southpaw pitched for Nogales High School in La Puente, playing football and basketball as well. It was in baseball, however, that he truly excelled, pitching an astonishing seven no-hitters.5 In the June 1965 draft, shortly after he turned 18, the Chicago Cubs selected House in the 11th round.6 He chose not to sign, going to the University of Southern California instead.

In the summer of 1966, after his freshman year at USC, House played with the Alaska Goldpanners, along with seven other USC players, racking up a record of 15-2 and helping the team to the amateur baseball world championship.7 His first start for the Panners was a one-hitter against the UCLA Bruins.8 His 177 strikeouts (in 137 innings) was the second all-time season total. 9

During the 1967 baseball season at USC – his sophomore year – he was 5-3 with a 1.43 ERA in 94 2/3 innings.10 Teaming up with pitchers Bill Lee and Mike Adamson, the pitching staff had an ERA of 2.26, the lowest in Trojans history.11 House also had a few acting roles. He was an extra in The Graduate (1967) and appeared in several episodes of the TV show Hogan’s Heroes.12

Atlanta made House their third-round pick (48th overall) in the June 1967 draft’s secondary phase. House reported his signing scout as Johnny Moore.13

Once signed, House pitched at three levels in 1967. He pitched in Double A (three weeks for the Austin Braves), Single A (five and a half weeks for the Kinston Eagles), and Triple A (for the Richmond Braves). He stuck with Richmond after a callup to pitch an exhibition game against the parent club (he worked seven innings and got a couple of hits).14 For the three teams combined, he was 3-3 with a 3.38 ERA. House stood 5-feet-11 and was listed at 180 pounds. His hobby at the time was “water sports.”15

His 1968 season was split between Shreveport and Richmond, but he spent the last 3½ months on the temporarily inactive list.

A medical issue cropped up in spring training with Atlanta in 1969, initially thought to be an elbow tendon problem. But what kept House out for a few weeks was a wrenched knee in June. He was able to start 19 games for Richmond, with a record of 4-7 and a 4.05 ERA. In the Arizona Instructional League, the Braves set him on what he knew was his likely path to the majors. The following spring, he said, “If I’m going to make it to the big leagues, I’ll make it as a relief pitcher.”16

In 1970, House appeared in 44 games for Richmond, 40 of them in relief. He was 6-5 (4.12 ERA). He almost quit baseball that winter, after not being added to Atlanta’s 40-man roster. House, who was married (in 1967), had a young daughter, Brittany, who needed an operation to address a congenital eye problem. His wife, Karren, urged him to give baseball one more year before perhaps joining the teaching profession. Braves farm director Eddie Robinson assured House, “If you come up short and need money for the operation, we’ll make up the difference.”17

House greatly appreciated the organization’s loyalty. Later, shortly after being traded to Boston following the 1975 season, he said he’d been treated well when he was struggling. He reiterated, “They stuck with me, and made me a relief pitcher. That’s what got me to the majors.”18

In 1971, House was 5-0, 2.17 in the early going, working short relief. He escaped what looked like a move to send him down to Double-A Savannah and was named to the International League All-Star team.19 He also improved his screwball. This was a pitcher who later wrote, “my best fastball was clocked at 82 mph on a ‘quick’ gun.”20 He credited Richmond Braves manager Clyde King for having confidence in him.21

The Braves brought House up to the big leagues in June after letting future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm go. House made his major-league debut in Atlanta on June 23, 1971, a Wednesday evening game against the Montreal Expos. He worked one inning in relief (the seventh) during a 6-3 defeat. He faced five batters and gave up one earned run on a double, wild pitch, and single.

Atlanta manager Lum Harris used House twice more in June and three times in July. Still without a decision, but with a 9.64 ERA, he was optioned back to Richmond on July 21. There he finished with a record of 7-3 and a 2.33 ERA.

Recalled on September 1, House worked in five games and brought his ERA down with each outing. His last game in 1971 was on September 30. Given a start against Cincinnati, he worked seven innings, allowing just four hits, and got the decision as the Braves won, 6-2. It was his first major-league win. At season’s end, his earned run average was down to 3.05.

House had not given up his studies. In 1972, he graduated from USC with a bachelor’s degree in Business. He continued in academia, earning an MBA from USC in 1974 and a second master’s degree in performance psychology in 1985 before earning his doctorate based in sports psychology in 1988.22 He also worked as a substitute teacher in the offseason.

House played the full Triple-A season for Richmond again in 1972, working 62 innings (with 55 strikeouts and 20 walks). His record was 5-8 for a sixth-place club, but House’s ERA was an excellent 1.45. His 20 saves was second in the IL. He was named the team’s Player of the Year. On September 1, he was once again called up to Atlanta. He worked in eight games, earning two saves and a hold with a 2.89 ERA.

Going into the 1973 season, the Braves perhaps had a surfeit of pitching.23 Yet House made the Opening Day roster, impressing with nine strikeouts in nine innings of spring training work. It also helped that he was left-handed and out of options.24 House spent the full season with Atlanta under manager Eddie Mathews. He worked in 52 games, going 4-2, with an ERA of 4.68, In his five seasons with Atlanta, the Braves never finished above third place.

A distinctive moment came on April 18, 1973, against the Giants – as a batter. In the top of the 11th, with runners on first and second and nobody out, House attempted a bunt but popped up to catcher Dave Rader, who executed the first unassisted double play ever made by a catcher at second base, doubling off Sonny Jackson. “House popped the ball straight up. Rader … caught it, looked toward second base where not a soul was around and then ran right up the middle of the diamond to tag the bag.”25

House became a much bigger part of baseball history in 1974 when Hank Aaron broke the all-time major-league career home run record. Aaron started the year with 713 career homers, one short of Babe Ruth’s then-current record. Aaron tied Ruth when he hit the very first pitch he saw in the 1974 season off of the Reds’ Jack Billingham. The Braves returned to Atlanta on April 8 to play the Los Angeles Dodgers. A crowd of 53,775 waited to watch Aaron make history. Watching from the bullpen was Tom House.

Based on his observations of Aaron’s hitting style, House predicted that if Aaron hit one out that night, it would land somewhere in left-center field. With that thought, House decided to park himself in that vicinity with the hope he’d be the one to catch the historic home run. “I had an indication [that Aaron would hit it to that area],” House said in a January 2021 interview. “I threw a lot of batting practice to Aaron.”26 House’s prediction came true when he caught Aaron’s home run off Al Downing in the bottom of the fourth inning. After gloving the historic ball, House ran on to the field towards Aaron, who was being mobbed in celebration by his teammates, fans, and media. House managed to wiggle through the crowd and hand the ball over to Aaron. “Here it is, Henry!” House said. “Thanks, kid!” Aaron replied as he tightly embraced his mother with tears in his eyes.27

“This is the biggest thing that has happened to me,” House said at the time.28 Interest in the ball Aaron hit was said to have made it worth as much as $25,000 at the time. House said, “If it was worth $25,000, it’ll be more than I’ll make all year.”29

Then, as at least one article proclaimed, the player who first became famous for catching a ball began to make a name for throwing one.30

House’s best season was 1974, when he pitched 102 2/3 innings, all in relief, with a 1.93 ERA and a 0.98 WHIP. He was 6-2 in 56 games. His 38 games finished ranked seventh in the National League, and his 11 saves placed him fifth. He said working in relief had helped him to be less emotional on the field. “I’m no longer a defensive pitcher,” he said. “I try to go after the hitter instead of having him come after me … When the phone rings now in the bullpen, I want it to be me.”31

In the offseason, House pitched for La Guaira in Venezuelan winter baseball, mostly as a starter. He appeared in 18 games, starting 14 of them. “I’ve been anywhere they play baseball. I pitched all over Latin America. When I was playing here in the States, the money … you couldn’t make a living unless you played winter ball, so I played winter ball six or seven years.” He may have overdone it, in that he got off to a poor start in 1975. “My first outing I think I gave up four runs before I got an out.”32

“I probably did [work too hard in the offseason] in retrospect, but it’s what everybody did to survive. I have no second guessing. I ended up doing OK that year.” After his first 10 appearances, though, he had an ERA of 14.46.

“For the first time, I knew I had a club made in spring training,” he said, “But I wanted so badly to prove that last year wasn’t a fluke. The external pressure was nothing to that I put on myself.”33 He progressively whittled down that ERA to a very good 3.18, at one point pitching 28 consecutive scoreless innings. Closing in 45 games, once again he earned 11 saves, this time to go with a 7-7 record. While in 1974, he had struck out 64 and walked 27, in 1975 he struck out 36 and walked the same number. But his 58 “House calls” were more than anyone else on the staff.34 House had worked 79 1/3 innings in 1975 and only surrendered two home runs.

House was traded from the Braves to the Boston Red Sox for Roger Moret on December 12, 1975. At the time, the Red Sox were coming off a historic season, falling just short of winning a hard-fought World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Moret, a left-handed starter, had been 14-3 in the regular season. The Sox had a number of starters, though, and manager Darrell Johnson said, “What we needed was one or two guys in the bullpen, and Tom House is one helluva relief pitcher.”35 Boston Herald writer Larry Claflin said, “House is probably nowhere near as talented as Moret, but he appears better able to fill a Red Sox need.”36

House was looking forward to playing with a team that had been a winner, but the Red Sox had a mediocre year in 1976 (83-79, third place in the AL East). Darrell Johnson was let go midway through the season, replaced by Don Zimmer. Perhaps struggling a bit to get used to the strike zone of American League umpires, House was used in 36 games. His ERA was 4.33 in just 43 2/3 innings of work. He’d had tendinitis in his left knee since June, but after giving up a walk-off home run to Chris Chambliss of the Yankees on July 25, he found himself in Zimmer’s doghouse and wasn’t used again until August 29, a stretch that included a 21-day stint on the disabled list. He offered a theory as to why Zimmer declined to use him for those weeks: coming off a spring in which he didn’t allow an earned run “may have led people to expect too much … I wanted to show the organization they hadn’t made a mistake. Maybe I tried too hard.”37 He required knee surgery after the season.

Zimmer said he wasn’t sure how much the knee had hampered House but said, “I think a lot of his problems were mental. He wanted so much to do well for us. It seemed as though the harder he tried the worse he got.”38 House himself wrote, “For me, the decline began in Boston. I was playing for the Red Sox and basically stinking up the place.”39

The Red Sox sold House’s contract to the Seattle Mariners near the end of May 1977. He had been 1-0 with Boston, but had been bombed for five runs in just a third of an inning in his first outing.40 The Sox traded Bobby Darwin to the Cubs to get another left-handed reliever, Ramon Hernandez, and then felt free to sell House’s contract. For his part, House said, “I didn’t do what was expected of me; I just couldn’t get going here.”41 He’d reportedly asked to be traded.42

Back in the city of his birth, House worked in 36 games for the Mariners in 1977 in their first year of operation, 11 of them starts, with a record of 4-5 and a 3.93 ERA. A batted ball that struck his hand put him on the 21-day DL in August.

In 1978 he made nine starts in the first couple of months and had 25 relief appearances overall, going 5-4 with a 4.66 ERA. A dislocated finger on his glove hand cost him a couple of starts in April. He did continue to insist he was more effective coming out of the bullpen.43 Seattle finished sixth in 1977 and seventh in 1978.

Near the end of spring training in 1979, the Mariners released House. Looking back, he wrote, “Okay, I was an experienced pitcher on an expansion ball club, and I did a fairly good job … putting up some adequate numbers. But still, my skills weren’t what they once had been, even though my know-how and my savvy enabled me to perform. My ability was declining, and I got released.”44

House’s final career totals in the majors were 29-23 with 33 saves and an ERA of 3.79. In 536 innings, he walked 182 batters while striking out 261. At the plate, he hit .257 in 38 at-bats. As a fielder, he made nine errors in 126 chances (.929).

Reflecting on his release years later, he said, “You might say I was born and died in Seattle. The hospital I was born in was on a hill overlooking the Kingdome, and I was released out of the Kingdome.”45

“When I look back, I had a solid career. I was a slightly below-average big-league pitcher and that’s exactly what my talent said I should be.”

It was a difficult time readjusting. His parents had “found a lot of joy” in following his career. “After my dad retired, they followed me around and watched me play in different cities. I can remember the first time I went into Dodger Stadium, my parents came down. I became a conversation piece in their circles – and part of their identity as parents – and when I got released, they were probably subconsciously angry that I got released, and very frustrated with the Seattle Mariners. They felt like the Mariners had hurt their son.

“The bottom line is that when I got back to the big leagues as a coach, [our relationship] was a lot more functional because I was able to relate to them not as a ballplayer but as a working human being.”46

There was one last attempt at playing ball before retiring. In April 1979, House started pitching in the Inter-American League for the Caracas Metropolitanos; he was 5-2 (2.36) in 13 games but, as he put it, “the league folded just before the Fourth of July, and I showed up at home in time for the holiday completely burned out on baseball.”47

He bought a “casual wear/sporting goods business” but it failed in less than four years.48 Fortunately, he had begun another career. The year after retiring as a player, he got a call from a friend who invited him to join the Houston Astros as a minor-league scout and pitching instructor. He coached in the Astros system for Sarasota in 1980 and for Columbus, Georgia in 1981. He then served as a minor-league instructor and as a coach in the San Diego Padres from November 1981 through 1984. The last two years, 1983 and 1984, were spent coaching the Las Vegas Stars of the Pacific Coast League. He pitched three innings in two games for the Stars in 1984.

That was the year the business went under, and House seemed to be losing everything, even moving into a rented house which itself burned to the ground two days before Christmas.49

He started 1985 as a scout for the Texas Rangers. In May he was named pitching coach for the Rangers and worked in that role for eight years, 1985-1992. The team was in the middle of the pack throughout. House didn’t hesitate to employ unorthodox ideas; among other things, he had pitchers throwing footballs in practice, explaining, “The motion required in throwing a perfect spiral is the exact motion used in pitching.”50 He picked up the nickname “Professor Gadget” because of his use of “biomechanical equipment, including a video camera and computerized strength tests.”51 He called it the “Digitizer,” a linkage of video to a computer for motion analysis.52 Needless to say, the use of video has become standard throughout baseball. House also stressed good and appropriate year-round physical conditioning.

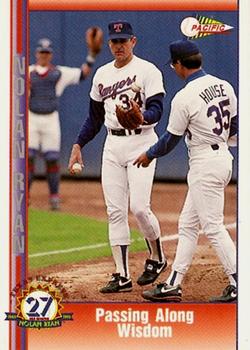

In 1989, Nolan Ryan joined the Rangers. Ryan had just turned 42, but he had an exceptional season, striking out a league-leading 301 batters – the first time since 1977 he had surpassed 300. House wasn’t shy about saying, “Statistically, Ryan was a better pitcher his last five years than his first five years.”53 Ryan introduced Randy Johnson to House. After three days working with House, Johnson said, “He showed me I could get six or seven inches out of my height in my delivery.” It was “one of the truly pivotal events of a career that would lead to five Cy Young Awards.”54

In 1989, Nolan Ryan joined the Rangers. Ryan had just turned 42, but he had an exceptional season, striking out a league-leading 301 batters – the first time since 1977 he had surpassed 300. House wasn’t shy about saying, “Statistically, Ryan was a better pitcher his last five years than his first five years.”53 Ryan introduced Randy Johnson to House. After three days working with House, Johnson said, “He showed me I could get six or seven inches out of my height in my delivery.” It was “one of the truly pivotal events of a career that would lead to five Cy Young Awards.”54

House and Ryan co-authored Nolan Ryan’s Pitcher’s Bible: The Ultimate Guide to Power, Precision and Long-Term Performance (Simon & Schuster, 1991) and Randy Johnson wrote the foreword to Fit to Pitch (Human Kinetics Publishers, 1996).

During this period, he called on his academic training to help himself and others. A deeply depressed teammate (whose anonymity House protected) called him and said he had a gun to his head. House was able to talk the player into counseling. He himself had experienced some of the problems of coping with the “real world” outside of baseball.

In April 1989, Contemporary Books published House’s book, The Jock’s Itch: The Fast-Track Private World of the Professional Ballplayer. The book was basically a popularization of his doctoral dissertation, dealing with what he called “terminal adolescence” – how professional athletes can have a difficult time adjusting to life outside the sports world.55 Baseball was something that simply grabbed a lot of those who played it and wouldn’t let go. House cited Jim Bouton’s famous last line from his book Ball Four: “You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.” House said, “I looked around at my peer group. The divorce rate was above average, there were bankruptcies and substance abuse of all kinds. Even with people who were financially secure, there was an unhappiness with the quality of their lives.”56

House has also been involved with a number of companies over the years; he was a partner in a firm named Biokinetics from 1986-2002.57

From 1990-94, he worked as a special instructor for the Chunichi Dragons of Nagoya, Japan. He worked for Bobby Valentine and the Chiba Lotte Marines from 1995-98. His involvement with the game in Japan dated back to 1977. An article in the San Francisco Chronicle described him as “working for the Padres as an international consultant with Japanese baseball.”58 House explained, “I started going to Japan when I was still playing for the Mariners (Japanese

American Baseball Summit, 1977). I consulted with the Dragons when I was coaching with the Astros and Padres, and with the Marines when I was with the Rangers.”59

After serving as Rangers pitching coach, he remained as a special assistant to the general manager and minor-league pitching instructor for the next two years, through 1994.

In the mid-1990s, House remarried. “My second wife, Marie, we’ve been married 25 years. I really learned, from my first marriage, what not to do. So this one has been a lot more functional. You have to work at marriage, like anything else. This has been a more normal relationship.”

House was also active running clinics for high school and college athletes.60 He has maintained a busy schedule of public speaking and lectures since 1995.

By 2002, House had begun an enterprise called Absolute Performance Group in Del Mar, California. According to the Chicago Tribune, through clinics and consultations, he saw 4,000 to 5,000 players a year. At the time, one of his bigger concerns was the unprescribed use of Ritalin and steroids. He felt that usage within major-league baseball ranks was close to 75%. “The philosophy in sports nowadays is you don’t get beat, you get outmilligrammed.”61 He said he had used steroids himself. Indeed, he attributed his multiple knee operations to extra weight the steroids had put on his frame.62 What’s more, he wrote, “there’s very little … that I haven’t actually experienced, tried, done, snorted, abused, used, whatever. I’ve been there.”63

In the same year – 2002 – he also founded the National Pitching Association, in Del Mar, which “provided pitchers, parents and coaches with three-dimensional motion analysis, functional strength screens, mental/emotional profiles and nutritional assessments.”64

House is involved with performance studies beyond baseball and football, He has served on the Board of Advisors of the Titleist Golf Performance Institute in Carlsbad, California since 2004.

In 2007, though by no means giving up his enterprises, Dr. House returned to the University of Southern California and served as pitching coach for the USC Trojans from 2008-2011. While there, House also established a nonprofit research center, the Rod Dedeaux Research and Baseball Institute.65

Tom House has three children – Brittany, Brooke, and Bryan – all from his first marriage. He says that all three of them have done very well. “They’re healthy. Grandkids are in the picture. Even though it was kind of a struggle toward the end of my playing career and leading into my coaching career, all’s well that ends well and right now we’re all just fine.”66

Asked whether he was prepared to slow down, and what he might do in later years, he explained that circumstances have prompted a transition – that first vacation being part of it. “I have Parkinson’s. I don’t have it bad, but there’s going to come a time when I’m not going to be able to move around. We’re preparing for that.

Asked whether he was prepared to slow down, and what he might do in later years, he explained that circumstances have prompted a transition – that first vacation being part of it. “I have Parkinson’s. I don’t have it bad, but there’s going to come a time when I’m not going to be able to move around. We’re preparing for that.

“I’m trying to retire. The National Pitching Association and 3DQB. I’m quietly turning ownership over to the kids – they’re not kids, they’re adults – who have been working for me and with me for the last 10 or 15 years. I’m lucky there. Our goal is in our mission statement. With everything we’ve done is to inform, instruct, and inspire – to help kids match information, master instruction, and then we’ll make a difference if we master that skill.

“I’m going to spend more time with Marie. Less time with athletes. I’ll probably never completely quit being a coach or a researcher, but I’ll definitely spend less time traveling or lecturing in front of groups.”

There may be another lasting legacy. In September 2020, he and mental performance coach Jason Goldsmith launched beta testing for a new app they called Mustard. Among the investors were Nolan Ryan and Drew Brees.

House explained what Mustard can offer. “Everything that I’ve been researching, everything that we provide elite athletes – from motion analysis, to functional strength training, to mental emotional management skills, to nutrition, sleep, and recovery – is now accessible on a cellphone. What would normally cost an elite athlete 15 or 20 grand, to come in for a weekend, we have now democratized so that the parents of a 12-year-old – if they have a cellphone and a backyard – they can film their daughter or their son, throwing or swinging, and through the app (it goes through the cloud and comes back) and it gives you the same efficacy as a $4,000 motion analysis in our lab. It’s democratized the information.

“Our goal … right now, in the world, there are 100-plus million adolescent athletes, male and female, 80% of which will stop playing their sport by age 14. What we’re trying to do with Mustard is to give them better information, allow them to have some fun learning, and stay healthy, and just hope that they participate in sports all the way through high school. That creates fans for sports but is also life-skill coaching from the athletic field.

“I think that sports and play – the power of play – are the last things that can help stabilize this weird world we’re living in right now.”

Last revised: January 11, 2022

- Related link: Listen to Tom House’s interview on SABRcast with Rob Neyer, Episode #104 (March 29, 2021)

Appendix: Publications by Tom House

There is not sufficient room here to list all the enterprises with which Tom House has been involved, all the positions he has held, his society memberships, and all the research studies with which he has been involved. We will, however, list publications he has either authored or co-authored.

Books Authored

Fastball Fitness (Coaches Choice Publishers, 2007)

Fit to Pitch (Human Kinetics Publishers, 1996)

The Pitching Edge (Human Kinetics Publishers, 1994; second edition 2000)

The Jock’s Itch (Contemporary Books, 1989)

The Winning Pitcher (Contemporary Books, 1989), also available in a Japanese edition

A Contemporary Guide to Pitching a Baseball (Champion Publishers, 1984).

Books Co-Authored

Arm Action, Arm Path, and the Perfect Pitch: Building A Million Dollar Arm (with Doug Thorburn) (Coaches Choice, 2009)

The Art and Science of Pitching (with Gary Heil & Steve Johnson) (Coaches Choice, 2006)

The Picture Perfect Pitcher (with Paul Reddick) (Coaches Choice, 2003)

The Baseball Coaching Bible (with 14 college coaches) (Human Kinetics Publishers, 2000)

The Stronger Arms and Upper Body Book (with Sean Cochran) (Human Kinetics Publishers, 2000)

Play Ball: Coaching Kids (with Dr. Coop DeRenne) (West Publishing, 1993)

Power Baseball (with Dr. Coop DeRenne) (West Publishing, 1993)

The Pitcher’s Bible (with Nolan Ryan) (Simon and Schuster, 1991), also available in a Japanese edition

The Diamond Appraised (with Craig Wright) (Simon and Schuster, 1989). also available in a Japanese edition.

House has also filmed and marked 30 instructional DVDs/videos on pitching and preparing to pitch, and one DVD/video series on conditioning for golf.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Evan Katz and fact-checked by Rod Nelson.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org. Thanks to Zach Sanzone for giving this biography a head start. Thanks, as well, to Rod Nelson and to Evan Katz for supplying additional information.

Notes

1 Author interview with Tom House, August 19, 2021. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from Tom House come from this interview.

2 Paraphrased, from Tom House, The Jock’s Itch (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989), 3.

3 Les Carpenter, “Tom House: The baseball eccentric who teaches Tom Brady how to throw,” Guardian, January 22, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/jan/22/tom-house-baseball-football-tom-brady. Accessed January 4, 2022.

4 He explained, “I’m taking my first vacation this year. I’ve never had a vacation before. I promised my wife that we’ll do two weeks somewhere. We’re going to go to Spain and Portugal in September.” Why there? “Because that’s where she wanted to go.”

5 Player questionnaire completed for William J. Weiss. For one article written after he had reached five no-hitters in two seasons, see “Prep Hurls 4th No-Hit,” Pasadena Independent, May 13, 1964: 19.

6 The 1965 draft was the first amateur draft.

7 Weiss questionnaire. In the first game of the championship played at Honolulu, House and Bill Lee combined to shut out the reigning champions from Japan, 5-0. Associated Press, “Alaska Shuts Out Japan Nine, 5-0,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1966: section 3, page 6. Bill Lee was a sophomore in 1966 and pitched for USC, too. See, for instance, “Trojans Down Broncs Twice to Win Crown,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1967: C6. http://www.pannervault.com/Seasons/1966/statistics.html. Accessed January 4, 2022.

8 “Panners Whip Bruins 8-0 As House Hurls 1-Hitter,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, June 14, 1966: 8. On August 18, he and Mike Adamson combined on a no-hitter against LaMesa in San Diego. “Panners Hurl No-Hitter Over LeMesa (sic),” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, August 19, 1966: 14.

9 http://www.pannervault.com/Statistics/Top-55-Panners/index.html. Accessed January 4, 2022.

10 https://web.archive.org/web/20190904011557/http:/pannervault.com/Scrapbook/h/house-tom_66.html. Accessed January 4, 2022.

11 https://usctrojans.com/documents/2021/1/28/2021_record_book.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2022.

12 Whiteside. An article in House’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, attributed to “1975 Atlanta Scorebook” says he earned $38.50 per day, and appeared as well in Beach Blanket Bingo, The Exorcist, and Camelot, as well as the Rat Patrol TV show. House later served as a consultant on the Disney movie, Million Dollar Arm and the Budweiser Challenge Reality Show.

13 Weiss questionnaire. However, the 1975 Atlanta Braves Media Guide credited his signing to Harry Minor.

14 House, The Jock’s Itch, 16.

15 Weiss questionnaire. Over the course of his career, House said his weight fluctuated from 160 to 205. Craig R. Wright and Tom House, The Diamond Appraised ((New York: Fireside Books, 1989), 20.

16 Jerry Lindquist, “R-Braves’ House Relieved as Reliever,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 30, 1970: 20.

17 Wayne Minshew, “Tom House Almost Opted for Teaching Profession,” Atlanta Constitution, June 27, 1972: 2H. House said of his wife, “Karren’s my biggest booster, my biggest fan.”

18 Larry Whiteside, “House warning: ‘No one pitcher can hold up bullpen’,” Boston Globe, March 4, 1975: 74.

19 Jerry Lindquist, “House’s ‘Star’ Appointment Quiets Early-Season Setback,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 22, 1971: B5, 8.

20 Craig R. Wright and Tom House, The Diamond Appraised, 281.

21 Jerry Lindquist, “House’s ‘Star’ Appointment Quiets Early-Season Setback.” See also “Rest Prescribed for Shoulder, Kester’s Future Still in Doubt,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 15, 1971: 70. After House got his first base hit of the season and won the Braves an 11-inning 6-5 game over Tidewater, he said of King, “I’d walk – no, run, though a wall for that man.”

22 The second masters and doctorate were from U. S. International University in San Diego.

23 Wayne Minshew, “Too Many Pitchers New Problem,” Atlanta Constitution, March 5, 1973: 3D.

24 Wayne Minshew, “Braves Choose Staff, House Earns Berth,” Atlanta Constitution, March 31, 1973: 1C.

25 Bob Stevens, “Bonds’ Homer Beats Braves,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 19, 1973: 47. In the bottom of the 11th, Barry Bonds homered off House to win the game for San Francisco, one of 49 home runs he surrendered in 536 innings of work.

26 Zach Sansone interview with Tom House on January 20, 2021.

27 “Tom House on teammate Hank Aaron,” MLB.com, January 22, 2021. https://www.mlb.com/braves/video/tom-house-on-teammate-hank-aaron

28 Associated Press, “37 Presidents,” Seattle Daily Times, April 9, 1974: 26. “I’m part of history,” House said.

29 Aaron gave House a Magnavox television set in appreciation. Wayne King, “Ball 715 Eludes Left-Field Bounty Hunters,” New York Times, April 9, 1974: 49.

30 “Braves’ House Adds to Mound Reputation,” Trenton Evening Times, June 20, 1974: 33.

31 Wayne Minshew, “House Building a Cool Approach,” Atlanta Constitution, June 7, 1974: 1D.

32 In fact, there was one out before the first run scored, but it was on a sacrifice bunt. There was also a passed ball, an intentional walk, and a fielding error behind him involved but eight run scored, six of them earned.

33 Wayne Minshew, “House Saves Braves’ 3-2 Victory,” Atlanta Constitution, May 9, 1975: 1J.

34 On July 5, in a game against the visiting Astros, he was accidentally hit in the back of the head by a bat that slipped out of the hands of Jose Cruz. He was knocked unconscious, but on waking showed he was well aware what the count was on the batter and seemed OK to continue. He got the next two batters out completing three scoreless innings of relief. “Braves’ Tom House on Target Again with Top Relief Form,” Atlanta Daily World, July 29, 1975: 2.

35 Peter Gammons, “Long on starters, in need of relief, Sox trade Moret for ‘Fenway lefty’ House,” Boston Globe, December 13, 1975: 21. House might not have been a strikeout kind, but he was the left-handed reliever the Red Sox felt they needed, seen as a “tough, intelligent man, and a worker.” Peter Gammons, “Analyzing the Red Sox: Enter Jenkins, House … and another pennant,” Boston Globe, April 4, 1976: 51. See also Bill Liston, “Sox ship Moret to Braves for relief ace,” Boston Herald-American, December 13, 1975: 17.

36 Larry Claflin, “Moret trade came as no surprise,” Boston Herald, December 13, 1975: 3. Moret was 3-5, with a 5.00 ERA, for the Braves in 1976.

37 Ray Fitzgerald, “A House divided,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1976: 33.

38 Zimmer as hopeful that 1977 would prove a better year. Larry Claflin, “Sox Mgr. Don Zimmer: ‘Yaz or Rice in left … Can’t let the Yankees jump off to a big lead,” Boston Herald, February 27, 1977: 32.

39 House, The Jock’s Itch, 118.

40 In just 7 2/3 innings with the 1977 Red Sox, he gave up 11 earned runs.

41 Bob Ryan, “Enter Hernandez, Exit House,” Boston Globe, May 29, 1977: 52.

42 Bill Liston, “Ellis claims he’d mean flag for Sox,” Boston Herald, May 11, 1977: 21.

43 Associated Press, “Last call does most all,” Dallas Morning News, June 7, 1978: 14.

44 House, The Jock’s Itch, 118.

45 The Kingdome was not yet built at the time of his birth; it began operating in 1976.

46 House also noted the toll that life as a ballplayer had taken on his Karren wife and their children. We ended up getting a divorce. The statistics on ex-ballplayers or elite athletes and divorce, the figures are upwards of 70 percent. They get used to a lifestyle that is not really functional for a family. You’re away from each other. In retrospect, the biggest mistake I made was not taking them with me everywhere I went. I felt like it was more important for them to have nine months of school and a stable environment. If I had to do it all over again, they’d travel with me everywhere I went.”

47 House, The Jock’s Itch, 121.

48 House, The Jock’s Itch, 122. In the August 2021 interview, House described it as “a sportswear emporium and a sporting goods store under one roof.”

49 House, The Jock’s Itch, 124.

50 Peter Gammons, “Texas Rangers finds trading goals bigger than reality,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, July 14, 1985: 58.

51 Associated Press, “Can House’s Gadgets Aid Slumping Staff?,” Laredo Morning Times, June 9, 1987: 11.

52 Tim Leone, “‘Professor’ and “Drill Instructor’ Guide Pitching Staff,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, March 3, 1988: 3-I.

53 Chris Jenkins, “He aids Cy Young winners, not Padres,” SignOnSanDiego (San Diego Union-Tribune), Mach 9, 2003. signonsandiego.com/sports/baseball/cjenkins/20030309-9999-1s9bbcol.html. Accessed June 22, 2021.

54 Jenkins. A 1989 article that discussed Ryan and House is Peter B. Sleeper, “Conditioning plays a big role in Ryan’s success,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), August 23, 1969: C-11

55 Frederick C. Klein, “Tom House: The Hurler’s Friend.” Wall Street Journal, March 13, 1987: 23.

56 Gergen.

57 Gannett News Service, “High tech could be future MVP for boys of summer,” Detroit News, October 12, 1989: D-1. The mission of Biokinetics was to “protect the human body from blunt impact injury, ballistic threats and blast effects.”

58 Dwight Chapin, “Mystery of the fallen Giants,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 26, 1977: C-1, C-5.

59 Email to author from Tom House, September 5, 2021.

60 See, for instance, Lee Diekemper, “Ex-professional pitcher Tom House shares tips with high school athletes,” Chicago Daily Herald, February 4, 2007: Section 5, 4. In his book The Diamond Appraised, he says he spent one year as a high school coach and 15 years teaching pitching to kids of all ages at the San Diego School of Baseball. The Diamond Appraised, 20.

61 Phil Rogers, “Ritalin use worries ex-ballplayer,” Chicago Tribune, June 4, 2002. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2002-06-04-0206040294-story.html. Accessed June 25, 2021.

62 Ron Kroichick, “House a ‘failed experiment’ with steroids,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 3, 2005: C-2. See also Associated Press, “Ex-pitcher clarifies comments on steroids,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, May 6, 2005: 4-C.

63 House, The Jock’s Itch, 99.

64 https://web.archive.org/web/20190904011557/http:/pannervault.com/Scrapbook/h/house-tom_66.html. See the National Pitching Association website at: https://www.nationalpitching.com/. Accessed January 4, 2022.

65 http://dedeauxfoundation.org/. Accessed January 4, 2022.

66 “My oldest daughter [Brittany] is up in San Francisco. She’s living in the Haight-Ashbury District. She’s married to a finish carpenter and his specialty is kitchens and bathrooms. All those old Victorians up there. He’s an artist and he’s booked for the next five years. My middle daughter Brooke married a sports marketing guy. He’s been with the Padres. He’s been with the Dolphins. He’s been with the Kansas City Royals. He’s been at Arizona State. They’ve moved around. Typical sports environment, but they’re doing very well. My son Bryan … I know he could have played and do well in college, and probably could have played pro ball, but when he was a senior on high school, he kind of packed it up and went on tour with Tony Hawk. He’s been involved in the X Games. He designs shoes now for Osiris and Vans – two or three of the shoe companies. He’s managed to carve out a nice little niche for himself.”

Full Name

Thomas Ross House

Born

April 29, 1947 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.