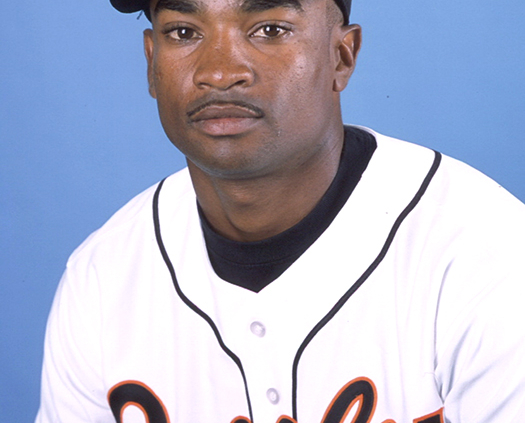

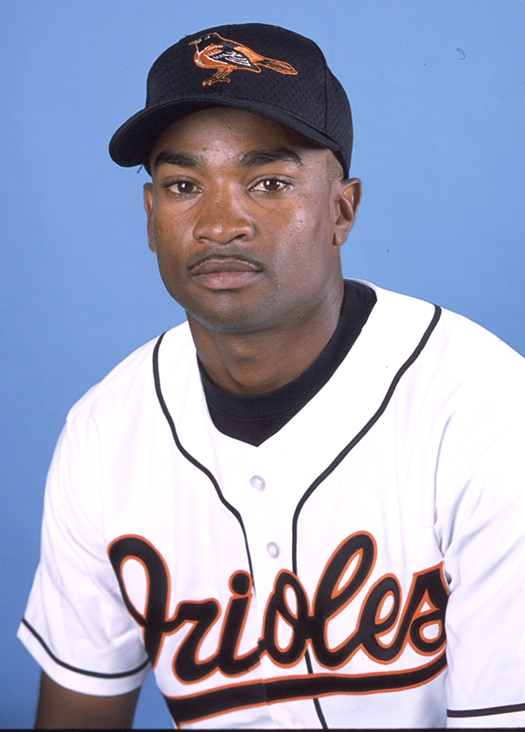

Carlos Casimiro

As of the end of the 2020 season, 789 players born in the Dominican Republic had played major-league baseball. Of the 363 who were primarily nonpitchers, 57 made All-Star teams and 35 appeared in a World Series for the eventual champions, but only 12 completed their careers with exactly one hit.1 Before Orioles rookie Carlos Casimiro did it on July 31, 2000, none of those Dominican one-hit wonders had ever hit safely in the first at-bat of his big-league debut.2

As of the end of the 2020 season, 789 players born in the Dominican Republic had played major-league baseball. Of the 363 who were primarily nonpitchers, 57 made All-Star teams and 35 appeared in a World Series for the eventual champions, but only 12 completed their careers with exactly one hit.1 Before Orioles rookie Carlos Casimiro did it on July 31, 2000, none of those Dominican one-hit wonders had ever hit safely in the first at-bat of his big-league debut.2

Carlos Rafael Casimiro Shaw was born on November 8, 1976, in San Pedro de Macoris. His father, Felix Antonio Casimiro Santos, was a driver at Ingenio Porvenir, one of the city’s signature sugar mills. Carlos’s mother, Gladys Martinez Stapleton Shaw, worked in one of the nation’s duty-free zones, designed to attract and stimulate foreign investment.

The couple had four children. Mercedes Luisa was the only girl, followed by Carlos and his younger brothers, Juan Pablo and the late Marcelo Augusto. In 2020 a middle-aged Carlos reflected on an alternate course his life could have taken. “If there was no professional baseball, the first thing that I would have focused on would’ve been my studies to become a lawyer, doctor, engineer, or an architect,” he said. “And if, in any case, I had not been able to finish my studies due to the economic situation we had in my family, I would be working in the duty-free zone.”3

Professional baseball was a possibility, of course. It had been played in the Dominican Republic since the late nineteenth century, but in the two decades before Casimiro’s birth, the number of Dominicans to reach the majors was only 46. Before he turned 8, however, that figure more than doubled. From 1990 to 1993, 51 new Dominicans debuted in the big leagues in the first four years of his teens alone.

Casimiro grew up in the Inve-Cea barrio, within a mile of Tetelo Vargas Stadium, home to the professional Estrellas Orientales team of baseball’s Dominican winter league. When he was 6, a sprawling sports complex opened just north of his home in preparation for the 1983 National Games, when more than 2,300 athletes competed in San Pedro de Macoris. Casimiro enjoyed playing basketball there, but baseball was king.

When outfielder Luis Mercedes became the 146th Dominican player on September 8, 1991, he made history as the first native of his country to be signed, developed, and deployed in a major-league game by the Baltimore Orioles.4

While the Orioles dove into the nation’s pool of talent relatively late, scout Carlos Bernhardt hustled to make up for lost time. A 1991 Baltimore Sun article described him as “a thick-armed former minor-league pitcher whose task is to dive into the wretched Dominican mass of cane fields and muddy streets, separate the prospects from the thousands of players, and give them their first push as professionals.”5 From 1969 to 1971, Bernhardt hurled a total of 17 innings in the Seattle Pilots and New York Yankees’ systems before his career was cut short by arm problems. His younger brother, Juan, played 154 games for the Yankees and Mariners.

When the Orioles fired two of their three Dominican scouts in 1987, Bernhardt became the club’s scouting supervisor in the country.6 They sent him some money to upgrade a ballpark in San Pedro de Macoris, and he rounded up supplies wherever he could. Months after Mercedes’s first hit, for example, the Baltimore-based Oriole Advocates group shipped Bernhardt two tons of boxes containing 663 bats, more than 600 uniforms, 491 balls, 380 gloves, 286 helmets, and dozens of sets of catching gear.7 Players like Armando Benitez and Manny Alexander – an All-Star closer and 11-year infielder, respectively – debuted with the Orioles over the next few years.

On April 15, 1994, a 17-year-old Casimiro joined the Orioles organization as well. “I managed to get signed by Bernhardt through my sister’s husband, who recommended me to the Orioles so I could sign with them,” he recalled. “The bonus was $2,500.”

The Dominican Summer League started in 1989 specifically to help the country’s prospects get started in pro baseball without the immediate additional pressure of adjusting to a new culture. The Orioles did not get their own DSL team until 1996, so Casimiro debuted with a combined team of Baltimore and San Francisco Giants prospects. Managed by former National League batting champion Matty Alou, it managed just an 18-52 won-lost record to rank 20th of the circuit’s 21 teams.

Casimiro returned to the DSL in 1995, this time with a Bernhardt-managed squad of Orioles and White Sox youngsters. The team was a little better, but after batting .259 with four homers in 108 at-bats, Casimiro took his .454 slugging percentage to Sarasota, Florida, to finish the season with Baltimore’s rookie-level Gulf Coast League affiliate. In 32 GCL contests, the 5-foot-11, 179-pound Casimiro hit .252 with a pair of home runs.

He played some shortstop in Sarasota but saw most of his action at second base. That offseason, Baltimore signed a perennial All-Star and Gold Glove Puerto Rican whom Casimiro admired to man that position in the majors. “My favorite player was Roberto Alomar,” he recalled. “I like the way and the aggressiveness of how he played baseball, and how easy he made the plays.”

The young Dominican was way below Alomar on the Orioles depth chart in 1996, but he helped the rookie-level Bluefield (West Virginia) Orioles win their division with an Alomar-like performance down the stretch. Mired with a .215 batting average on July 25, Casimiro batted .339 the rest the way to finish at .276.8 His 10 home runs ranked third in the circuit behind 6-foot-5, 283-pound teammate Calvin Pickering, and he ranked in the circuit’s top five in runs scored and steals, and the top 10 in doubles and total bases. His all-around performance earned him recognition as the Appalachian League’s all-star second baseman.

That fall Casimiro joined the Estrellas Orientales for the first of six winter-ball seasons with his hometown team. Prior to the 1997 season, he got his first couple of mentions in the Baltimore Sun. “O’s think 20-year-old could be strong offensively,” reported Buster Olney.9 Though beat writer Peter Schmuck noted that Baseball America rated the Orioles farm system the most barren in baseball, based on his conversations with major- and minor-league sources, he described Casimiro as the most promising second-base prospect in the Baltimore organization.10

The Orioles moved Casimiro up to the full-season, Single-A Delmarva Shorebirds in 1997. The team was based in Salisbury, Maryland, near the state’s Eastern Shore. Early in the season, the local newspaper profiled him briefly. In addition to disclosing that he liked to eat pasta and preferred to hear merengue music when he came up to bat, the Dominican said that God was his hero, “faith in God” was his good luck charm, and all he knew about Salisbury was that it was by the beach. (Ocean City, Maryland, sits 30 miles to the east.) While Casimiro’s prediction that the Baltimore Orioles would win the World Series looked good until the wire-to-wire AL East leaders stopped hitting in the ALCS, his goal “to have a good year and win the South Atlantic League championship” worked out nicely.11

On April 10 against the Greensboro (North Carolina) Bats, Casimiro became the first Shorebirds player to homer twice in one game.12 He did it again against the Hagerstown Suns on June 28. Though he batted only .243 with nine homers overall, Casimiro led Delmarva with eight triples, swiped 20 bases, and tightened his defense after committing eight of his 21 errors in April.13 When the Shorebirds beat the Bats, 8-1, in Greensboro to win the South Atlantic League title, he went deep and combined with Pickering for 7 RBIs.14

The Orioles added Casimiro to their 40-man roster, and he spent part of his offseason playing for the Maui Stingrays of the Hawaii Winter League. When Baseball America released its updated prospect rankings in January, he was rated 13th in the Baltimore system overall, but the organization’s top middle infielder.15

Casimiro’s first big-league spring training was marred by a hand injury he’d suffered while lifting weights in the Dominican. Early in camp, he aggravated it on a check swing.16 He spent the season with Baltimore’s advanced Single-A Frederick (Maryland) Keys in the Carolina League, where he formed the keystone combination with shortstop Jerry Hairston Jr. early in the season. Prior to Hairston’s promotion to Double-A that summer, Casimiro shifted to third base briefly to allow his double-play partner to gain experience at second.

By season’s end, Casimiro topped the Keys with 47 extra-base hits, including 15 home runs, demonstrating the combination of soft hands and surprising power that made him a prospect. On the other hand, his .236 batting average and 98/25 strikeout-to-walk ratio illustrated how much progress he still needed to make in terms of patience and hitting breaking balls. “I’m feeling a little more comfortable at the plate,” he remarked after blasting a grand slam and a solo homer against the Lynchburg Hillcats on July 29. “I’m just thinking of watching the ball and hitting it up the middle.”17

Against Winston Salem on August 11, he hit another grand slam to win a game in the ninth inning,18 but a broken left wrist he suffered in the final week of the month relegated him to spectator status. Casimiro’s scheduled trip to the Maryland Fall League to gain more seasoning with the Bowie Nationals was canceled.19

When Alomar left the Orioles as a free agent in December, Baltimore signed Delino DeShields to replace him. DeShields fractured a thumb in spring training, however, and a healed Casimiro was one of the options to fill in for him. Instead, the Birds went with Jeff Reboulet as their Opening Day starter, while Jesse Garcia, a more experienced rookie, made the team as a backup. Casimiro wound up in Bowie, home of the Orioles’ Double-A Eastern League Baysox.

Bowie skipper Joe Ferguson told reporters early in the year that he thought the Dominican could hit .300,20 but Casimiro’s average declined for the third straight season, to .221. “At that time, I didn’t have much help from anyone,” Casimiro said. “The only person who helped me a lot for me to become a major leaguer was David Stockstill. He was a hitting coach in the minors.”

Stockstill, the 1979 Midwest League MVP when he clubbed 27 homers for the Wausau Timbers, was a Missouri native who’d played in the Mexican League for eight seasons. He later became the Orioles’ director of international operations.

The good news for Casimiro in ’99 was that he ripped 18 homers to lead the Baysox and missed only two games. His 73 runs scored tied for most on the team, and his 64 RBIs were his best single-season mark as a pro.

He returned to Bowie in 2000, albeit not until the final week of April after remaining in Florida to mend a spring-training shoulder injury.21 With another young Dominican, Eddy Garabito, manning second base for the Baysox, Casimiro shifted to third and made a whopping 30 errors in 84 games. In early May, he was one of five players suspended after a 20-minute brawl with the Erie SeaWolves, ignited when Bowie’s pitcher intentionally threw the ball at an opponent during a rundown.22 After getting off to a strong start at the plate, Casimiro endured a two-month stretch in which he batted only .218 between May 10 and July 9.23 When he blasted a game-winning three-run home run against the Akron Aeros on June 24, it was his first homer in 140 at-bats and snapped an 0-for-22 slump.24 By the end of July, though, an opportunely timed .328 hot streak over 17 games raised the Dominican’s average to .262.25

Meanwhile, in Baltimore the disappointing Orioles had the American League’s next-to-worst record. In the four days before the July 31 trade deadline, they sent away seven veteran players in five separate deals. In return, the Orioles received only four players for their major-league roster, one of whom wouldn’t arrive in time for that night’s game. To supplement their shorthanded roster, the Orioles looked to Bowie, only a 30-minute drive south of Baltimore.

Casimiro woke up the morning of July 31 with a strong feeling that it would be his day. He called former Baysox teammate Luis Matos, an outfielder who’d been called up to the Orioles six weeks earlier, and told him, “Matos, when you go back to Baltimore, you will take me with you.”

Matos picked him up and took him to Prince George’s Stadium in Bowie, where manager Andy Etchebarren gave the Dominican the news. “When I heard him, I became frozen, I could not articulate a word from the emotion I felt,” Casimiro recalled. “At that moment I told myself, ‘You did it, your dream has come true.’ Immediately, I phoned my family to give them the news that I had been called up to the big leagues.”

That afternoon, in the locker room at Oriole Park at Camden Yards, Casimiro found a jersey with his name. He became the third Baltimore player to wear uniform number 36 in the 2000 season.

From the first-base dugout, he watched Albert Belle’s two-run homer give Baltimore a first-inning lead against the visiting Twins. Designated hitter Jeff Conine followed by drawing a walk. By the time Conine’s turn in the order came around again, the DH had left the ballpark to join his wife for the delivery of the couple’s third child.

Therefore, with two on and two out in the bottom of the third against Minnesota southpaw J.C. Romero, Casimiro debuted as a pinch-hitter. The public-address announcer told the crowd of 32,661 that it was the 23-year-old’s first major-league at-bat. After working the count to two balls and two strikes, he fouled off one pitch26 before lining the next one into right-center field for a two-run, standup double. “Casimiro doffed his helmet at second base as the crowd rose to its feet with a thunderous ovation,” reported Orioles beat writer Roch Kubatko in the Baltimore Sun.27

“Everyone rose from their seats to applaud and welcome my first hit and debut in the big leagues,” Casimiro recalled. “That was a moment of great emotion for me.”

By the time he got to bat again in the fifth, the Orioles led 5-2, and the Twins had gone to the bullpen. He struck out swinging to end the inning against fellow San Pedro de Macoris native Hector Carrasco. “I did know him well before we faced each other in the majors because he and I practiced together in a baseball program here in the Dominican Republic before I was signed by Baltimore,” Casimiro explained.

He grounded out in his third at-bat, but the Orioles held on for a 6-5 victory. The next night Casimiro was in the starting lineup, batting fifth as Baltimore’s DH against left-hander Mark Redman. He went 0-for-5 but his bases-loaded groundout in the first inning drew first blood in the Orioles’ 10-0 rout behind Mike Mussina. There was a time in baseball history when Casimiro would have received credit for a game-winning RBI, but that statistic became defunct after the ’88 season. “I’ve just got to do my job,” the rookie told reporters afterward. “The manager at Bowie told me I was going to be here only four of five days, but I don’t know.”28

Casimiro watched from the bench as the Orioles’ modest four-game win streak came to an end on Wednesday afternoon. Trent Hubbard, one of the players Baltimore had acquired, finally arrived from Atlanta and went straight into the starting lineup. On Friday in Tampa Bay, Conine returned to the team. When infielder Mark Lewis came off the disabled list before Saturday’s contest, it was back to the minors for the young Dominican.

Casimiro joined the Rochester Red Wings for the last month of the International League play. In 24 games, he connected for four home runs, but batted just .222 in his first taste of Triple-A ball. He did not get called back up to the majors in September, and the Orioles outrighted him to Rochester after the season.

After attending Orioles spring training as a nonroster invitee in 2001, Casimiro returned to Rochester as a left fielder. He hit only .235 in 48 games, however, and was sent back to Bowie in June. Playing mostly third base in his 80 games there, his average sank to .222. By season’s end, his overall .270 on-base percentage and .338 slugging mark between two levels were the worst marks he’d fashioned as a pro. His 122 strikeouts, versus 25 walks, showed him trending the wrong way, too.

That fall, Casimiro traveled to Taiwan as part of the Dominican Republic’s roster for the Baseball World Cup tournament.29 The Dominicans finished eighth out of 16 teams.

From 2002 to 2006, Casimiro played in the Italian Baseball League. “After being a free agent from Baltimore, I waited for several months to see if I could get a contract with another team in the USA,” he said. “But seeing that I did not get with anyone, I decided to go to Italy to play. Because of the way in which the bosses treated me, I decided to come back for four more years.”

His .409 batting average led the Serie A1 circuit in 200230 for an otherwise overmatched Paterno Citta dei Normanni club that was relegated to Serie A2 for 2003 after finishing last with a dismal 7-46 record. When the team returned to Serie A1 in 2004, it moved up to sixth place in the 10-team circuit, led by Casimiro’s .945 OPS, the league’s fifth best. Only Willie Canate, with 9, outpaced his eight homers.31 Casimiro’s 6 home runs won the crown in 2005, but Paterno sank bank to the basement. In 2006 he finished his Italian career with the T&A San Marino squad. “My best experiences were knowing the cities of Rome and Venice,” he recalled.

By the time he finished playing in Italy, Casimiro had married the former Wendy Margarita Santana Madrigal and become a father. Their son, Carlos Rafael Casimiro Santana, was born first, followed by brother Luis Ismael and sisters Dafne Isabel and Karla Maciel in the decade of the 2010s. “It drives me to work 100 percent in everything I do to give my family a better life, and that motivation is my children, my wife and my mother,” he said. “If it wasn’t for them, maybe I’d be involved in drugs trying to earn a lot of money but thank God I have them.”

In 2014 Casimiro returned to baseball as the manager of the Oakland Athletics Dominican Summer League team, a position he still held as of 2020. “One of my friends, a coach who worked with them, recommended me to the bosses for a job. That’s how I started working with Oakland,” he explained.

At Oakland’s Juan Marichal Complex in Boca Chica, about 25 miles west of San Pedro de Macoris, Casimiro sought to impart lessons he learned in pro ball to a new generation of prospects. “First, they must be on time to be able to take advantage of the moment and work on what they need,” he said. “Second, they must work for a reason, something that encourages them to give 100 percent in everything, so that their development is more effective. For example, a good reason would be their mother, or a major leaguer that they choose to visualize playing like in the big leagues. Finally, think big, that they are always the best.”

Reflecting on his all too brief Orioles career, he said, “I am very proud of the way I managed to hit safely in the majors although I was a little nervous about playing in the big leagues for the first time. But at the same time, I feel disappointed that I could not have played longer in the big leagues so I could help my family.”

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Carlos Casimiro (email interview with Malcolm Allen on September 19, 2020) and to SABR colleagues Miguel Casey and Alberto Rondon for their help with translating.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Three Dominicans, Estevan Florial, Cristian Pache, and Jesus Sanchez, got one hit apiece in their 2020 debuts.

2 Alberto Lois of the Pittsburgh Pirates collected his only hit in his first at-bat on October 1, 1978, but he’d appeared in two previous games without a plate appearance. On May 29, 2005, Napoleon Calzado matched Casimiro’s feat. Calzado, like Casimiro, did it for the Orioles at Camden Yards.

3 Unless otherwise noted, all Carlos Casimiro quotes are from an email interview with Malcolm Allen, September 19, 2020.

4 Dominicans Ozzie Virgil, Jose Mesa, Jose Bautista, Juan Bell, and Francisco de la Rosa all played for Baltimore before Mercedes, but all five started their careers in other organizations.

5 John Eisenberg, “A Field of Dreams in the Third World,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 1991: 1A.

6 Eisenberg.

7 “Oriole Advocates Ship 2 Tons of Equipment to Dominican,” Baltimore Sun, May 19, 1992: 5B.

8 1998 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 62.

9 Buster Olney, “Minor Goes Backdoor to O’s,” Baltimore Sun, January 390, 1997: 1C.

10 “Peter Schmuck, “O’s Working Farm, but Far from Harvest,” Baltimore Sun, April 9, 1997: 1D.

11 “Player: Carlos Casimiro,” Daily Times (Salisbury, Maryland), April 11, 1997: 22.

12 “Casimiro’s 2 HRs Lift Shorebirds, 5-0,” Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1997: 5D.

13 1998 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 62.

14 “Shorebirds Batter Bats, 8-1, Capture South Atlantic Title,” Baltimore Sun, September 12, 1997: 6D.

15 Peter Schmuck, “Once O’s ‘Twin,’ Brewers Dream of Their Own Rise,” Baltimore Sun, January 25, 1998: 11D.

16 Roch Kubatko, “Alomar Makes Strong Left Turn,” Baltimore Sun, February 24, 1998: 5D.

17 Rich Scherr, “Casimiro Supplies Power with Slam, Solo Shot,” Washington Post, July 30, 1998: C6.

18 Casimiro’s 2000 Fleer Tradition baseball card.

19 1999 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 67.

20 Brian Straus, “Baysox Spruce Up in Spring,” Washington Post, April 7, 1999: M22.

21 Kent Baker, “Young Baysox Ready to Grow Up,” Baltimore Sun, April 6, 2000: 7C.

22 Kent Baker, “6-7 Stahl Has O’s Thinking Big After Shaky Start,” Baltimore Sun, May 8, 2000: 7E.

23 2001 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 58.

24 Roch Kubatko, “Pulled the Wrong Way in Spring, Maloney is on Tear Back to Majors Healthy,” Baltimore Sun, July 3, 2000: 7E.

25 Roch Kubatko, “Chance for Casimiro,” Baltimore Sun, August 2, 2000: 7D.

26 Dan Rodricks, “A Judge, a Senator and 30,000 Shriners,” Baltimore Sun, August 2, 2000: 1B.

27 Roch Kubatko, “Casimiro Debuts in Fine Style as Young Cast Wins Again,” Baltimore Sun, August 1, 2000: 6E.

28 Kubatko, “Chance for Casimiro.”

29 “Aguilas Ceden Jugadores,” La Prensa, October 31, 2001. prensa.com/impresa/deportes/Aguilas-ceden-jugadores_0_501699827.html (last accessed October 4, 2020).

30 “Tripla Corona,” file:///C:/Users/Malcolm%20Allen/Downloads/2014%20MIKE%20ROMANO%20curriculum%20(2).pdf (last accessed October 4, 2020), 28.

31 “Le Statische del Campionato 2004,” baseball.it/2004/09/22/le-statistiche-del-campionato-2004/ (last accessed October 4, 2020).

Full Name

Carlos Rafael Casimiro

Born

November 8, 1976 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.