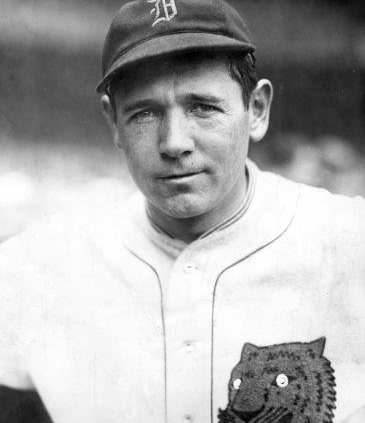

Harry Heilmann

When Harry Heilmann reached the big leagues, he had a daunting task ahead of him. The Detroit Tigers were counting on him to replace Hall of Famer Sam Crawford in right field. Crawford batted over .300 for his career and retired as baseball’s all-time leader in triples. The Tigers quickly found out that their new right fielder was just as good of a hitter — one of the best right-handed hitters in the history of the game — who would win four batting titles, top the .400 mark and become one of the dominating players in the 1920s.

When Harry Heilmann reached the big leagues, he had a daunting task ahead of him. The Detroit Tigers were counting on him to replace Hall of Famer Sam Crawford in right field. Crawford batted over .300 for his career and retired as baseball’s all-time leader in triples. The Tigers quickly found out that their new right fielder was just as good of a hitter — one of the best right-handed hitters in the history of the game — who would win four batting titles, top the .400 mark and become one of the dominating players in the 1920s.

Harry Edwin Heilmann was born on August 3, 1894, in San Francisco. He was one of the few early stars in the game to grow up on the West Coast. But baseball was just as prevalent there, even though there was no major league team west of St. Louis until the 1950s.

Heilmann came from a baseball family. His older brother Walter was perhaps the best up-and-coming pitcher in San Francisco because of his devastating curveball. But his career, and life, were cut short when he drowned attempting to swim to shore after his boat capsized.

Harry was working as a bookkeeper in California before he became a professional baseball player. In 1913, he joined Portland of the Northwestern League. In his first game, as a professional, he went 0-for-3 and made an error at first base. Things improved over the course of the season, as he finished the season at .305.

Fred Lieb, in his history of the Tigers, describes his early years: “The handsome, pleasant-faced Irish-Dutchman from San Francisco was destined to become, next to Tyrus Raymond Cobb, Detroit’s greatest hitter. He was acquired in another of Tigers owner Frank Navin’s strokes of good fortune. Heilmann was with Portland, Oregon, of the old Northwestern League, in 1913, and Fielder Jones, manager of the old Hitless Wonder White Sox, was president of the circuit. He recommended the young slugger to Navin, and the price tag supposedly was only $1,500.”

Heilmann made his debut with the Tigers on May 16, 1914. He entered the game as a pinch hitter and went 0-for-1 against the Boston Red Sox. Though he was poised to take over Crawford’s spot in right field, “Wahoo Sam” would not retire for a couple more years. So, Heilmann was optioned to San Francisco in 1915, playing all over the diamond before he reached the majors again. It put him in good stead, as over the course of 136 games in 1916 Heilmann played right field, left field to give Bobby Veach a day off here and there, first base, second base — even center field, where Ty Cobb roamed for Detroit on his way to the highest career average in history (.366). While the young Californian hit .282, it was playing with Cobb that really taught Heilmann the secret of becoming an elite hitter.

On the Tigers, he was known as “Slug” and “Harry, the Horse.” A former Golden Gate Park player, he attended Sacred Heart College in his native city and then St. Mary’s. His mother was of Irish extraction, and his father of German origin, and the good Heilmanns were much concerned in the early days of Harry’s ball playing. When he brought home some of his early baseball pay, they feared Harry was doing something which wasn’t honest. But his parents eventually figured out that Harry was that good. A big 200-pounder, he stood 6-foot-1. But without Cobb’s speed, he beat out comparatively few infield hits. He had to line ’em out.

It didn’t start so promisingly for Heilmann, however, who struggled while being shuffled around to different positions. He batted just .225 in 68 games in 1914 and was sent back to the minors. Heilmann returned to the Tigers in 1916 and hit .282 and .281 in 1917. His most famous act during that time, however, was on July 25, 1916, when he dove into the Detroit River to save a woman from drowning. He received a thunderous ovation at the ballpark the following day. In 1918, Heilmann missed half of the season while on a Navy submarine and hit just .276 in 79 games.

In 1919, Heilmann returned, but not to the outfield. Detroit placed him at first base in 1919 and 1920 and he led the American League in errors at his position both seasons. But while his fielding struggled, his hitting finally came around, batting .320 in 1919 and .309 in 1920.

The Tigers realized the experiment with Heilmann at first base was not what they had hoped, and he returned to the outfield in 1921. It turned out better than anyone in the organization could have hoped for. Heilmann, Cobb and Veach — who led the AL in RBIs three times — formed one of the greatest outfields in baseball history. But Heilmann was the most impressive in 1921. He battled Cobb, who was now also Detroit’s manager, in a neck-and-neck race for the American League batting title, eventually outlasting his tutor with a .394 average. Cobb finished at .389. “When he beat Ty Cobb out for the batting championship Ty didn’t really talk with him again,” daughter-in-law Marguerite Heilmann said. “He was kind of irrational about it and wasn’t really dad’s cup of tea.”

It was an adjustment playing for Cobb the manager, who platooned his own players and Heilmann was part of the shuffle. On a couple of occasions early in his first season as manager, he even benched Heilmann, who was in the process of winning the first of his four batting championships, in favor of lefty Chick Shorten.

That was one reason Cobb’s relations with his best ballplayer were less than congenial. Another was his determination to keep Heilmann in right field and play rookie Lu Blue, a stylish fielder and competent switch hitter, at first base. Then, in Washington in June, Cobb changed his batting order without telling Heilmann, so that the big Californian was batting out of turn in the first inning when he hit a drive into the distant bleachers in left-center with Donie Bush aboard. As Heilmann crossed the plate, umpire Billy Evans called him out and disallowed both runs. Finally, Cobb insisted that Heilmann ride Bobby Veach, who was too good-natured and easygoing for Cobb, on the theory that if Veach stayed mad he would hustle more. It apparently worked, because Veach batted .338 and drove in 128 runs that year. But when, after the season, Cobb failed to tell Veach about putting Heilmann up to the mischief, Veach and Heilmann became permanently estranged.

Heilmann had high hopes for 1922, and so did the Tigers. But the hopes were dashed when he broke his collarbone and played just 118 games. He racked up a .356 average when he was playing, but it wasn’t enough to keep the Tigers in the pennant race.

Slug picked up 1923 right where he left off and had the best season of his career, beginning with a 21-game hitting streak in April and May. He joined Cobb as the only players in Tigers history to bat .400 as he paced the American League with a .403 average, beating Babe Ruth by ten points. Ted Williams (.406 in 1941) is the only American League player to reach .400 since Heilmann. Slug laced 211 hits, scored 121 runs and drove in 115, smacked 44 doubles, 11 triples, and 18 home runs, and slugged .632. Even more impressive for a slugger, he only struck out 40 times all season. He walked 74 times to earn an on-base percentage of .481, which was second in the AL behind Ruth. After the season, Heilmann, in his offseason job, sold Ruth a $50‚000 life insurance policy. The beneficiaries were Mrs. Ruth and their adopted daughter, Dorothy.

In 1924, Veach left the Tigers for Boston and Detroit, who had platooned Veach and a rookie named Heinie Manush, created another tremendous outfield combination of Cobb, Heilmann and Manush. All three won batting titles for Detroit and eventually reached the Hall of Fame. Heilmann batted .346 in 1924 while Manush finished at .289 and Cobb batted .338.

Heilmann had started a peculiar trend of winning batting titles every other year. In 1925, it was no different as Slug made up a deficit in September to overtake Hall of Famer Tris Speaker on the final day of the season and bat .393, four points ahead of Speaker. After Harry made three hits in the first game of a season-ending doubleheader, several of his teammates figured he had passed Speaker by the width of a hair. They suggested: “Why don’t you lay off in the second game? You’ve got the title won.”

“Not me,” said Harry. “I’ll win it fairly, or not at all. I’ll be in there swinging.” He went 3-for-3 in the second game of the doubleheader to capture the title.

Once again, he failed to win back-to-back batting titles, but did hit an impressive .367 in 1926. He was hitting so well that the Detroit fans and club had a special day to honor him. The red-letter day of the year was Harry Heilmann Day, August 9. A crowd of 40,000 Heilmann fans crammed into Navin Field to pay homage to Harry the Horse. Larry Fisher, the automobile king, came across with a new car, the Knights of Columbus with a diamond stickpin, and Paddy Pexton with a hunting dog with a huge green ribbon around his neck. And they put the usual jinx on their hero. Harry went hitless in a free-hitting game which Detroit lost 9-8 to the New York Yankees. But Slug whacked the ball plenty on days when he was not the special guest of honor.

Winning the batting title that season was his teammate Manush at .378. The bigger story that season, however, was a letter that former Tigers pitcher Dutch Leonard wrote to Heilmann saying that he had turned over letters written to him by Joe Wood and Ty Cobb to AL president Ban Johnson‚ implicating Wood and Cobb in betting on a Tigers-Cleveland game played in Detroit on September 25‚ 1919. He charged that Cobb and Speaker conspired to let Detroit win to help them gain third-place money. At a secret meeting of AL directors‚ it was decided to let Cobb and Speaker resign with no publicity. But‚ as rumors spread‚ Judge Landis took charge of the matter and held hearings‚ at which Leonard refused to appear. Cobb and Wood admitted to the letters‚ but say it was a horse racing bet‚ and contended Leonard was angry for having been released to the Pacific Coast League by Cobb.

Everyone expected Heilmann to win another batting crown in 1927 after winning one in odd years since 1921. He was near the league lead for most of the season but trailed Philadelphia’s Al Simmons by one point heading into the final day of the season. In an odd twist to the race, it was Simmons who was now Cobb’s teammate as the Georgia Peach had joined the Athletics that season. In a moment of irony, Cobb’s 4,000th hit came against Detroit that season, a double that got past Heilmann. The Tigers played a doubleheader against Cleveland on the final day and Heilmann made the most of his at bats smashing seven hits in nine trips to the plate to finish at .398 — six points ahead of Simmons. In his first two times up, Harry smacked doubles. In his third time at bat, he rolled the ball to third base and was out. Fred Lieb, in his book The Detroit Tigers, describes it in detail:

“The next time up, he pulled a Lajoie: He bunted, caught the third baseman flat-footed, and beat it out. It gave him three out of four in the game. Some of the fans implored him to retire. ‘You’ve got Simmons beat; call it a day, Harry,’ they yelled. But not Slug; he knocked the next one out of the lot for a home run. Would he come back for the second game and risk the championship which now was his? There need be no doubt of the answer. Every man, woman, and child in the park cheered him as he went out to right field at the start of the game. He hit a homer, a double, and a single in four at-bats. What an exhibition of guts when the chips really were down!”

It was the fourth time he had won the batting title and all four over future Hall of Famers. He finished second to Lou Gehrig in the A.L. Most Valuable Player voting that year. (Babe Ruth, who had one his greatest seasons, was ineligible per the rules of the era because he had previously won the award in 1923.)

In 1928, Heilmann’s batting dropped off, at least for his standards, as he batted .328. Manush again batted .378, but lost the batting title on the final day to fellow future Hall of Famer Goose Goslin. Heilmann’s career took a painful turn in 1929 when he began to have arthritic pain in his hands. He fought through it and batted .344 with 41 doubles and knocked in an amazing 120 runs in 125 games. His career got even more painful when, after that impressive season, the Tigers put him on waivers. Slug had not only had a great season, but he turned in one of the most impressive decades in the history of the game. In the 1920s, he led the American League with a .364 average. He averaged 209 hits, 105 runs scored, 43 doubles, 11 triples, 15 home runs and 123 RBIs per 154 games. His .558 slugging percentage was fourth during the decade, only trailing Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Al Simmons. Hitting was contagious on the Tigers. Heilmann was part of an outfield that batted over .300 as a unit in seven of the ten seasons in the 1920s.

Knowing his best years were behind him, but determined his career wasn’t over, Heilmann moved to the National League after the Cincinnati Reds claimed him on waivers. He played 142 games and batted .333. Heilmann briefly retired in 1931 then finished his career in 1932 as a player-coach and appeared in 15 games, batting .258. Heilmann finished his career with a .342 batting average, which still ranks 12th on the all-time list. In seventeen seasons in the majors, Heilmann slapped 2,660 hits, 542 doubles, 151 triples, 183 home runs, scored 1,291 runs, and knocked in 1,537 runs with eight 100-RBI seasons.

In 1933, Heilmann launched the second half of his career in baseball. He became the radio broadcaster for the Tigers, where he remained for seventeen years. He was the first former player to ever become a play-by-play broadcaster when he was hired by WXYZ (now WXYT) radio in Detroit. Fans were captivated as Heilmann delivered the current action on the field to their homes while giving them a glimpse of baseball during his playing days with stories of Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb. It wasn’t an easy career jump. He took public speaking classes and had to learn to read the ticker tape since radio announcers did not broadcast from away games in those days. He used his imagination to make the game interesting and build excitement for those away games, where messages he received might simply say, “single to left.” He always found time to give back, too. During World War II, he traveled to the Middle East as part of a baseball group entertaining troops.

Heilmann was a terrific broadcaster, and his voice was in homes all over Michigan and the Midwest. But tragedy struck during spring training in 1951. “He was diagnosed with lung cancer and he didn’t want anyone to know it,” daughter-in-law Marguerite Heilmann said. “He was a very private person. They didn’t do much treatment in those days. You were mostly just sent home to die.”

Harry Heilmann died of lung cancer at age 56 in Detroit on July 9, 1951, three days before the All-Star Game at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. The game began with a moment of silence in Heilmann’s honor. Cobb, who visited his old teammate in the hospital, told Heilmann that he had earned election to the Baseball Hall of Fame, which gave him much joy. But it wasn’t true. Heilmann wasn’t elected until the following year. It was a rare moment of selflessness for Cobb, who knew his teammate deserved the honor and would eventually get it.

His legacy lives on through the memories of his family and stories passed down from grandfather, to father, to son about his ferocious hitting in Detroit. Harry Heilmann Jr. passed away in 2002, leaving grandsons Harry III, who lives in Colorado and Dan, who lives in Michigan. It was tough maintaining strong relationships when players were on the road for so much of the year. “My father and grandfather had a good relationship but my grandfather traveled so much,” grandson Dan Heilmann said. “Between spring training and school, camp and the baseball season, there wasn’t that much time. The road trips in those days were long. He could be gone a month and it could have been when my father was at camp for a month in the summer.”

But Heilmann made the most of the time he did have with his family, and with the Detroit community, both as a player and a broadcaster. “What players did for the community back then is what makes the Tigers what they are today. They are much more disciplined and professional now, but because of that, they have lost the community feel,” Dan Heilmann said. His grandfather was one of the players who gave back to the underprivileged and identified himself as a Detroiter. “He invented the word class,” daughter-in-law Marguerite Heilmann said. “The man was outstanding when it came to not only his professional persona but his personal behavior was of a true gentleman.”

Photo credit

Harry Heilmann, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Sources

Alexander, Charles. Ty Cobb. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

baseballlibrary.com

Lieb, Fred. The Detroit Tigers. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1946.

Michigan History magazine, 1995

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Sacred Heart College News

thebaseballpage.com

Full Name

Harry Edwin Heilmann

Born

August 3, 1894 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

July 9, 1951 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.