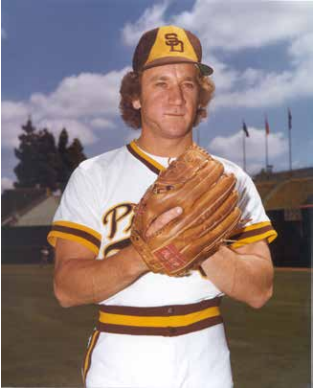

Randy Jones

“It happens every time. They cheer him even before he throws a ball. It’s the way he comes across. He’s a humble person, the underdog making good. People can relate to him. He’s not that big in stature (6 feet, 180 pounds) and he is not overpowering on the mound. Randy’s the common man’s pitcher.” — John McNamara, 19761

“If I was a pitcher, I’d be embarrassed to go out to the mound with that kind of stuff.” — Mike Schmidt, 1976.2

Not overpowering is putting it mildly. Randy Jones’s assortment of junk was frustrating to the best of the hitters in the National League. Switch-hitting Pete Rose after, at one point, going 4-for-29 against Jones, decided to try his luck left-handed. After a frustrating effort on June 30, 1976 where Rose went 0-for-3 with a walk, Rose said, “Left-handed, right-handed, cross-handed, he still gets you out.”3

Not overpowering is putting it mildly. Randy Jones’s assortment of junk was frustrating to the best of the hitters in the National League. Switch-hitting Pete Rose after, at one point, going 4-for-29 against Jones, decided to try his luck left-handed. After a frustrating effort on June 30, 1976 where Rose went 0-for-3 with a walk, Rose said, “Left-handed, right-handed, cross-handed, he still gets you out.”3

“I’d lose something in the fifth or sixth inning of a lot of those games,” Jones said, reflecting on his 1974 season. “It was a tough year. I lost a lot of confidence by the second half of the season. People said it takes a good pitcher to lose 20 games, but I never bought that.”4

Randall Leo Jones was born on January 12, 1950, in Fullerton, California. His father, Jim, was a plant superintendent for a large agricultural company. Randy graduated from Brea-Olinda High School and attended Chapman University in Orange, California. In his senior year of high school, he went 8-2 with a 0.91 ERA and 110 strikeouts. He was named to the Irvine League All-Star team, and was the starting pitcher in the Orange County Prep All-Star game. At Chapman, during this first two varsity seasons, he played for coach Paul Deese. In his freshman year, his fastball was impressive. But on a pitch to the plate that season, he stumbled off the mound and pulled some tendons. Thereafter, he got by on junk. In 1970 Chapman was rated number 1 in the NCAA’s College Division. After an impressive win against USC in his sophomore year, he said, “I was confident. I challenged their hitters. I threw my fastball and slider over the plate, daring them to hit the ball. They didn’t.”5 Jones went 11-4 as a sophomore with a 1.75 ERA, and was named second team All-American.

Jones married his high-school sweetheart, Marie Stassi, on October 10, 1970. They had two children, Staci, born in January 1975, and Jami.

After his sophomore and junior years, Jones played summer ball for the Glacier-Pilots of Anchorage in the Alaska Baseball League. The team, managed by Paul Deese, participated in the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas, in 1970. Jones pitched a complete game in the semifinals to advance his team to the finals.6 After the 1971 season in Alaska, the Glacier-Pilots returned to Wichita and, in the final game, Jones pitched the team to a 5-4 win over the Fairbanks Gold-panners. The game wasn’t decided until the bottom of the ninth inning when Anchorage tallied the winning run off Fairbanks pitcher Dave Winfield.7 It capped off a season during which Jones went 14-1 with three wins in the National Baseball Congress tourney.8Deese and Jones remained lifelong friends and eventually Deese, a successful businessman, counseled Jones on his post-baseball business ventures.

By Jones’s senior year, with the zip out of his fastball, and most of the scouts looking the other way, he was effective nonetheless. Under coach Bob Pomeroy, Jones went 11-4 with a 1.42 ERA during the regular season. In the NCAA District Eight Tournament he shut out Cal State on a three-hitter, prompting opposing coach Al Matthews to say, “He wasted his fastball and made us hit his breaking pitches.”9

Although his fastball was nonexistent by the end of his four years at Chapman, Jones emerged with a degree in business, planning to go into real estate if he couldn’t continue in baseball. However, one scout did keep his eye on the young Jones. Both Marty Keough and Cliff Ditto of the Padres noticed that he could be a success. Keough said, “He threw strikes. He got a quick breaking ball and he got people out.”10 He was drafted in the fifth round by the San Diego Padres in 1972, and signed for a bonus estimated at $3,000.

Jones began his pro career in 1972 with the Tri-City Padres in the Northwest League. It was a short stay; he pitched in only one game before being promoted to Alexandria, Louisiana, in the Texas League. He went 3-5 with a 2.91 ERA and returned to Alexandria the next season. After going 8-1 in 10 starts with the Aces to start the 1973 season, Jones was called up to the Padres in June, never to return to the minor leagues. The key to his success that season was a sinkerball he learned from Padres minor-league pitching instructor Warren Hacker.11 Hacker “showed me how to place my fingers differently and how to apply pressure with them,” Jones said.12 The lefty went 7-6 with a 3.16 ERA in 20 games for San Diego that year.

The next year, 1974, Jones was 8-22 (with a 4.45 ERA) in 40 games, and he led the National League in losses. It was a tough season. As the losses mounted, Jones said, “With any luck, my record could be 14-9 instead of 7-16. When you get people to hit the ball on the ground and the ball consistently finds a hole, it isn’t bad luck – it’s no luck at all.”13 Seventeen of his losses were by two runs or less. As the season wore on and the losses mounted, he was dispatched to the bullpen in September and four of his last five appearances were in relief, including a two-inning save against the San Francisco Giants on September 24. However, in his final appearance of the season, two days later against the Los Angeles Dodgers, he faltered and was charged with four runs in 2⅔ innings as Los Angeles won, 5-2, in 10 innings. It was Jones’s 22nd loss and the 100th loss for the Padres, who finished last in the NL West.

After working with pitching coach Tom Morgan, Jones altered his mechanics and found success in 1975. He said Morgan “made some fundamental changes in my delivery; now my body is doing all the work, my arm isn’t getting tired. I feel like I could pitch forever. It’s incredible.”14 And some days, he seemingly had to pitch forever, since the team still wasn’t giving him much in the way of run support.

On May 19 Jones outdueled John Curtis of the St. Louis Cardinals, pitching a 10-inning one-hitter that ended when the Padres’ Johnny Grubb hit a homer in the bottom of the 10th. The next high point of the season came on July 3 against Cincinnati. He took a perfect game into the eighth inning when Tony Perez reached second on an error by shortstop Hector Torres. Showing the wisdom of former Dodger pitcher Billy Loes, Jones said that “he lost it in the stadium lights. That was obvious to me.”15 Two batters later, Bill Plummer broke up the no-hitter and shutout with a double that scored Perez, knotting the game at 1-1. Jones was prepared to pitch into the night. “I had made up my mind that they would have to drag me out of there. If [manager John] McNamara wanted to remove me, he would have had to tie me up.”16

Although Jones could eat up the innings, he did not eat up the clock. He dispensed with the Pirates using only 68 pitches in a May 24 shutout, and defeated the Astros 6-1 in 1:37 on August 6. He won 20 games that year, led the NL with a 2.24 ERA, and was selected for his first All-Star Game, where he picked up a save. He finished second to Tom Seaver in the Cy Young Award balloting and was named the National League Comeback Player of the Year.

Jones’s success continued into 1976. For his performance in 1975, San Diego owner Ray Kroc increased his pay from $24,500 to $65,000. Jones went 16-3 in the season’s first half (an All-Star break win total that no one as of 2017 has equaled). His celebrity status was such that the Padres attendance figures more than doubled when he pitched. After the great start, there was speculation that he could be the next 30-game winner, but he took everything in stride. “There’s no sense thinking about number 30 until you’ve won 29,” he said. “A good start isn’t necessarily an indication of what’s going to happen for the whole season. I’ve had success taking games one at a time and omitting everything else from my mind. Guys get in trouble when their minds get astray and they start thinking way ahead.”17

Despite his great performance in 1975, Jones did not get national hype until the night of June 9 when the Mets were in San Diego with their Cy Young ace Seaver, and 42,972 fans came to see their hero Jones. His achievements were well known to the home folks, who turned out in droves to see Randy. The game was scoreless for four innings before the Padres scored single runs in the fifth, sixth, and eighth innings to win, 3-0. Jones’s record went to 11-2, as he scattered seven hits, struck out four, walked none, and sent the folks home in 2:10.

In one stretch, from May 17 to June 22, Jones tied a 63-year-old National League record by going 68 consecutive innings without issuing a walk. During that stretch, he faced 265 batters. The record had been set by Christy Mathewson of the New York Giants in 1913. On June 22, after striking out San Francisco’s Darrell Evans to tie the record, he had received a standing ovation from the crowd of 29,940. The ovation continued as Jones came to bat in the seventh inning with the score tied 2-2. He singled and, with one out, came home on Tito Fuentes’ two-run homer. Jones’s streak ended when he walked Giants catcher Marc Hill leading off the eighth inning. The count went to 3-and-2 and Hill fouled off two pitches before taking a sinker for ball four. “Before I let it go, I knew it was going to be a ball,” Jones said. “My arm was too far behind my body. I was pushing, I was too anxious.”18 There was no further scoring, and the 4-2 victory extended Jones’s record for the season to 13-3. The win put the Padres into second place, a half-game ahead of the Dodgers, and kept San Diego within five games of the league-leading Reds.

For the second consecutive year, Jones pitched in the All-Star Game. He started, and his appearance was vintage Jones. In his three innings, seven of the outs were on groundballs. There was one foul popup and one strikeout. Jones was the winning pitcher when the NL won the game, 7-1. After the All-Star Game, his numbers trailed off a bit. He also came very close to tragedy. On the evening of August 4, the Padres returned home from Atlanta after a game in which Jones lost 1-0, putting his record at 18-6. Driving home from the airport, possibly at a speed faster than that of his fastball, Jones failed to negotiate a curve near his home and, as his wife said, “The telephone pole was sitting in the front seat.”19 A passing driver took Jones to the hospital. His only injuries were cuts to his face and neck. Lucky to be alive and with more than 30 stitches, Jones was back on the mound on August 10 at New York’s Shea Stadium, losing a 5-4 decision to Jerry Koosman. In all, he was 4-8 after the accident, largely due to lack of support. In his last six losses of 1976, the Padres scored three runs or less, and they were shut out twice. Nevertheless, Jones finished the season with a 22-14 record, and a 2.74 ERA. Never known for the speed of his pitches, he struck out just 93 despite leading the league with 315⅓ innings pitched.

Jones started 40 games that season and had 25 complete games, both league highs. And he worked in a hurry. His games on average lasted little more than two hours. On August 27, when he shut out the Expos 2-0, he sent the folks home in 1:38. On September 19, in the first game of a doubleheader at Houston, Jones completed the game (a 3-2 loss) in 1:42. His quickest outing was on July 20, when he shut out Philadelphia 3-0 in 1:31. And his sinker was working to perfection. As pitching coach Roger Craig said, “It isn’t so much as how much it sinks as when it sinks. It sinks late. It looks good on top of the plate and then sinks under the bat after the batter’s committed himself.”20

In 2016, reflecting on that 1976 season and the crowds that came to cheer him on, he said, “I had never seen anything like it; I don’t know that anybody in San Diego had. Our ballclubs in those days weren’t very good. (They had never had a winning season before 1976.) We had talent, but we didn’t have consistency. But the boys really seemed to step up on the days I pitched, and the fans really got behind me.”21

He also commented, “Everybody is mystified that I could complete 25 games. You have to remember that I completed 25 games and I didn’t average 100 pitches in those games. I’d throw 89, 88, 92 pitches in a nine-inning game. That was philosophically how I approached the game. I went out in the first inning and I wanted to throw three pitches. I definitely tried to get the third one on the first pitch.”22

But 1976 was Jones’s last year as an elite pitcher. In his last start, he felt a tear in his forearm. He had severed the nerve attached to his biceps tendon. Jones had surgery after the 1976 campaign to repair a nerve injury, but never again had a season above .500. “It was years of futility and frustration,” he recalled in 1998.23

Jones won just six games in 1977 but they included a vintage performance against the Phillies on May 4 in San Diego, his only complete game of the season. He pitched against Jim Kaat and won 4-1 in a mind-boggling 1:29 to bring his record at the time to 2-4. Of the 27 Phillies outs, 19 came on groundballs. Not everyone was happy about the swiftness of the game. Ted Giannoulas (a/k/a The San Diego Chicken) said, “That game took money out of my pocket because as an hourly wage worker back then making $4 an hour, I could only put down an hour and a half on my timecard. So I made $6 on that game, then they took out taxes. For the rest of the year, I would swear the names Randy Jones and Jim Kaat under my breath.”24 But after that single major success, Jones’s ERA still stood at 4.85. His record for the season wound up at 6-12 with an ERA of 4.58.

Jones began the 1978 season slowly. After winning his first decision against Atlanta, on April 20, he was ineffective in his next two starts, finishing April at 1-2. He recorded his first shutout of the season on May 10, defeating Chicago 1-0. In a season marked by inconsistency, Jones lost four games in June but came back to win three games in July. His second shutout of the season, a 1-0 win over the Dodgers on August 1, put his record at 9-9. The Padres had a disappointing season. They fell out of contention early and, despite a winning record of 84-78, finished in fourth place, 11 games behind the division champion Dodgers. Jones bounced back from a terrible 1977 to record two shutouts and seven complete games, His season’s record was 13-14 with a 2.88 ERA.

Hopes were high in the spring of 1979. Manager Roger Craig said, “He’s got his confidence back. I think he’ll have a big year. Randy will win three or four more games because Fred Kendall is catching him again. He trusts Kendall and that’s important because he never shakes off a pitch. Randy is the only good pitcher I’ve ever seen who doesn’t shake off his catcher’s signs.”25Pitchers are notorious for bragging about their hitting, but on May 13, 1979, Jones had a stolen base that was the first theft by a pitcher in the then 11-year history of the San Diego franchise. It came at home in the third inning against Mike Scott of the Mets. He had reached on an error by Scott and manager Craig, with Gene Richards at the plate, put on the hit-and-run play. Richards swung and missed and Jones got into second ahead of the throw from Mets catcher John Stearns.26 It was his only career stolen base. He tired in the eighth inning and did not factor in the decision as the Padres won in extra innings. Jones’s 1979 season pretty much mirrored 1978, as he went 11-12, but his ERA rose to 3.63. There were no shutouts, but he did complete six games, as the Padres dropped to 68-93 and finished in fifth place in the NL West.

In the spring of 1980, things were looking up for Jones. He was 4-2 and coming off three consecutive complete-game shutouts when he faced the Pirates on May 21 in the first game of a doubleheader. He took a 3-0 lead into the bottom of the fourth inning but then the troubles started again. During the inning he felt a pain in the right side of his ribcage. “I tried to compensate by throwing with my arm instead of my body, and strained the nerve in the arm again,” Jones said. “My fingers went numb. Damn, it was frustrating.”27 He remained in the game until the bottom of the sixth inning, and was not involved in the decision. Pitching in pain for the balance of the season, Jones won only one of his last 12 decisions and had a 5.32 ERA during that stretch. For the season, he was 5-13 with a 3.91 ERA.

After the 1980 season, Jones was dealt to the New York Mets for a pair of prospects, Jose Moreno and John Pacella. He won eight games over two seasons with the Mets before retiring. The 1981 season was a disaster. He lost his first five decisions, but it was a team effort: Of the 36 runs he allowed in his first eight starts, only 20 were earned. The Mets were challenged when it came to fielding groundballs. Jones’s only win came on May 31 against the Cubs. He allowed one run in 6⅓ innings of his 6-1 victory. For the strike-shortened season, Jones was 1-8 with a 4.85 ERA.

Jones’s first appearance of 1982 indicated that things would be different from 1981. During the offseason, he had done a great deal of running and he came to spring training in great shape. New Mets manager George Bamberger gave Jones the ball on Opening Day and he beat the Phillies and Steve Carlton, 7-2 at Veterans Stadium. Jones pitched the first six innings, scattering four hits and allowing only one run. The over-anxious Phillies were swinging at bad pitches and three of the outs were on easy comebackers. After the win, he said, “I had good concentration and, believe it or not, I warmed up on the mound (in chilly 41-degree weather). My sinker began to come around in the second inning and I got a lot of important outs with it. I had excellent concentration. My mental approach today was perfect.”28 One week later, at Shea Stadium, Jones triumphed again over the Phillies, 5-2, in the Mets’ home opener.

Things were looking up for Jones and for the Mets, who were coming off five straight losing seasons. The signs outside had said, “The Magic is Back” since 1980. But was it? Jones got off to a great start, winning six of his first eight decisions. On May 10 he hurled his first complete game since 1979, beating the Padres 3-2 and reducing his ERA to 2.60. On May 18, against Cincinnati at Shea Stadium, he got his fifth win though he was charged with four runs in seven-plus innings. After his sixth win, a four-hit shutout at Houston on May 23, the Mets were in second place with a 23-18 record, 1½ games behind the National League East-leading Cardinals.

But Jones was only 2-2 at home, and Shea Stadium had been a nemesis to him over the years. It all began in 1973 when, in his major-league debut on June 16, he entered the game in relief and yielded his first major-league hit, a home run by an aging Willie Mays, and continued through his time with the Mets. In 1982 he won at home only once after May 23, and his record sank from 6-2 on May 23 to 7-10 at the end of the season. His ERA rose from a low of 2.60 on May 10 to a disturbingly high 4.60 at the end of the season. On the road in 1982 he was 4-2 with a 2.37 ERA, but he was 3-8 at home with a 7.47 ERA. As Jones’s fortunes got worse, so did those of the Mets. After the good start, they finished the season in sixth place in the NL East with a 65-97 record. The Mets had several young guns coming up through the minors and Jones, hoping to catch on with another club, was released, on his own request, after the season.29 He was philosophical when he said, “A manager can’t use a pitcher who can’t win at home and I understood when Bamberger took me out of the rotation.”30

When 1983 rolled around, Jones went to spring training with the Pirates as a non-roster invitee. He was released on March 27.

For his career, Jones was 100-123 with an ERA of 3.42. He had 73 complete games, of which 19 were shutouts.

After his playing days were over, Jones returned to San Diego, where he became a fixture. His residence in Poway is about 25 miles north of San Diego. He tended to the string of car washes he had opened during his days with the Padres. His other business pursuits revolved around food; he started in his sister’s catering business, became a food broker, and eventually opened his own barbecue stand at the ballpark. He also did pregame and postgame shows.31 In his time as a food broker for AGS Foods, he traveled to military food services operations, mixing business with pleasure. In addition to making sales calls, he conducted baseball clinics for children of military personnel.32

Jones’s number was 35 retired by the Padres in 1997, and two years later he was a member of the first group inducted into the Padres Hall of Fame. He remained, as of the end of the 2016 season, the Padres’ leader in starts, complete games, shutouts, and innings pitched.

Jones also worked with young pitchers. He had put an ad in the local newspaper offering to give pitching lessons to youngsters, and had 35 students. In 1990, a 12-year-old saw the ad and his folks gave Jones a call. “I remember vividly the four, five years we spent in the backyard with Randy,” said 2002 Cy Young Award winner Barry Zito. “When I did something incorrectly, he’d spit tobacco juice on my shoes, Nike high tops we could barely afford, he’s spitting tobacco juice on them.” In his teaching, it was Jones’s goal that his best students “that showed a burning desire” would be shown his Cy Young trophy. What Zito learned from Jones was “the mental side, never giving in.”33

Jones also worked with the Padres Volunteer Team, which was launched in February 2015 to help nonprofits, including the USO, for which in September 2015 the group put together 300 “we care” packages for US military families.34

He threw out the ceremonial first pitch at the 2016 All-Star Game in San Diego. In November 2016, years of tobacco use caught up with Jones and he was diagnosed with throat cancer. He started treatments at Sharp Hospital the following month, and completed his treatment on February 1, 2017. To thunderous applause, he threw out the first pitch on Opening Day 2017 in San Diego. When he was tested on May 1, he was hoping to be given a clean bill of health.35 The following day, the call came from his doctor: he was cancer-free. “To say I’m cancer-free today will give somebody else a little hope,” he commented. “If they have any hopes, don’t doubt it. You’ve got to put the work in, but the process works.”36

Postscript

Jones died at the age of 75 on November 18, 2025.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, the Randy Jones player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and the following:

Broderick, Pat. “Former Padre Still Pitching … Food This Time,” San Diego Business Journal, September 22, 1997: 8.

Denman, Elliott. “Jones Returns to Top of Heap,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, May 23, 1982: B3.

Shaw, Bud. “You’ve Got to Believe in Jones Now,” Philadelphia Daily News, April 9, 1982: 93.

Notes

1 Ron Fimrite, “Uncommon Success for a Common Man,” Sports Illustrated, July 12, 1976.

2 Dave Distell, “Fans Flocking to See Randy Jones,” Los Angeles Times, June 24, 1976.

3 Distell.

4 Al Doyle, “Former Cy Young Award Winner, Randy Jones,” Baseball Digest, August 2001: 64.

5 Al Carr, “Randy Jones – The ‘Vow Boy’ of Chapman’s Baseball Varsity,” Los Angeles Times, May 7, 1970: III-14.

6 Merrill Cox, “Anchorage, Peck Here, Peck There, Colorado Tumbles,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, August 30, 1970: 6F.

7 Bob Stewart, “Pilots Win Alaskan ’71 Rush for NBC Gold,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, September 1, 1971: 17.

8 Andy Williams, “City Pays Tribute to National Champions,” Anchorage Daily News, October 11, 1971: 9.

9 “CHCS Down to Last Strike,” Hayward (California) Daily Review, May 26, 1972: 27.

10 Dave Anderson, “Randy Jones Wins Without Fastball,” New York Times, June 10, 1976: 49.

11 Jack Murphy, “The Best of Seasons for Randy and Marie,” San Diego Union, July 6, 1975: H-1.

12 “Randy Jones Wins Without Fastball.”

13 Phil Collier, “Pittsburgh Surges by Pirates, 7-3,” San Diego Union, August 10, 1974: C-1.

14 Murphy, “The Best of Seasons for Randy and Marie.”

15 Murphy, “The Best of Seasons for Randy and Marie.”

16 Murphy, “The Best of Seasons for Randy and Marie.”

17 Distell.

18 Phil Collier, “Jones Notches 13th, Ties N.L.’s No-Walk Record,” San Diego Union, June 23, 1976: C-1.

19 Jack Murphy, “Randy in Stitches; the Padres Aren’t Laughing,” San Diego Union, August 6, 1976: C-1.

20 Jack Flowers, “Randy Jones: Shades of Denny McClain, Dizzy Dean,” Pensacola (Florida) News Journal, June 24, 1976: 1-C.

21 Jeff Sanders, “’Crafty Left-Hander Had It All Working – Randy Jones Wins 1976 National League Cy Young Award,” San Diego Union-Tribune, March 13, 2016: S-7.

22 Kirk Kenney, “Rush Hour (and a Half) – Forty Years Ago Today Padres Beat Phillies in a Mere 89 Minutes – Unthinkable Today,” San Diego Union-Tribune, May 4, 2017: S-1.

23 Paul Gutierrez, “Catching Up With Randy Jones,” Sports Illustrated, August 3, 1998.

24 Kenney.

25 Murphy, “Glory Was Sweet; Randy Craves Encore,” San Diego Union, March 11, 1979: H-1

26 United Press International, “Jones’s Stolen Base First by Padre Pitcher,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, May 14, 1979: B-4.

27 Dick Young, “Ready to Play Some Hardball,” New York Daily News, February 6, 1981.

28 Hal Bodley, “Phillies Can’t Keep Up With Mets’ Jones,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, April 9, 1982: C-1.

29 Russ Franke, “Jones Makes a Pitch for More Major Fun,” Pittsburgh Press, February 23, 1983: D2.

30 Charley Feeney, “When Randy Jones Was a Met, Shea Was Just No Place Like Home,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 21, 1982: 10.

31 Gutierrez.

32 Doyle.

33 “Former Cy Young Pitcher Helped Develop Zito Into Award Winner,” Hamilton (Ontario) Spectator, November 8, 2002: E05.

34 Stephanie R. Glidden. “Volunteers Pitch in to Help Get Care Packages to Our Military,” San Diego Business Journal, September 28, 2015: 41.

35 Dennis Lin, “Randy Jones Visits Padres Camp; Hopes to Be Declared Cancer-Free,” San Diego Union-Tribune, March 23, 2017.

36 Jeff Sanders, “Padres Report – An Emotional Jones Says Cancer Is Gone,” San Diego Union-Tribune, May 3, 2017: S-5.

Full Name

Randall Leo Jones

Born

January 12, 1950 at Fullerton, CA (USA)

Died

November 18, 2025 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.