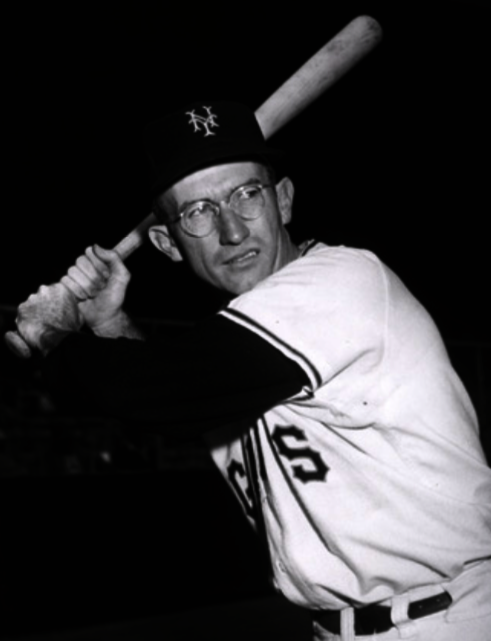

Bill Rigney

“The fascinating thing about baseball is that everyone knows that it is a business and you have to win and you have to draw fans to be successful, but you still have fun along the line doing all that,” Bill Rigney once said. “I don’t think I ever woke up one day in my life that I didn’t want to go to the ballpark.”1

“The fascinating thing about baseball is that everyone knows that it is a business and you have to win and you have to draw fans to be successful, but you still have fun along the line doing all that,” Bill Rigney once said. “I don’t think I ever woke up one day in my life that I didn’t want to go to the ballpark.”1

And to the ballpark he went. In 1938 Bill Rigney signed with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League and was farmed out to the Spokane Hawks in the Class B Western International League. In 16 games he batted only .083 but was nonetheless bought up to Oakland, where he hit .265 in 24 games. Rigney was still in the game more than six decades later, back in Oakland with the A’s in an executive capacity. He was still with the A’s when he died in 2001.

Rigney was born in Alameda, California, on January 29, 1918, the second of four children born to George and Eleanor Rigney. His father was in the tile business and eventually owned a tile-distribution company. Growing up, Bill watched his father and uncles play semipro ball for the Rigney Tile Company and rooted for the New York Giants. When he came to the majors it was with the Giants and he continued in the Giants organization as a player, minor-league manager, and major-league manager for 15 seasons. He was the team’s manager when the New York Giants became the San Francisco Giants in 1958.

Early on, Rigney attracted favorable reviews. When the 21-year-old was in the Oaks training camp in 1939, veteran teammate Billy Raimondi said, “Bill must have been born to be a ballplayer. He has natural baseball sense. It is something you can’t explain, can’t put your finger on, but it exists just the same.” Manager Johnny Vergez was also high on Rigney, but felt that he would benefit more by spending some time in the lower minors.2

In 1939 Rigney played for the Vancouver Capilanos and the Bellingham (Washington) Chinooks in the Western International League. At Bellingham he was stricken by appendicitis and his season ended after 60 games in which he hit .270. In 1940 he batted .276 for the Topeka Owls of the Class C Western Association. He returned to Oakland in 1941 and spent two years with the Pacific Coast League Oaks. At the time, the closest major-league team was in St. Louis, 2,000 miles away. Most teams in the PCL operated independently and many former major leaguers populated the rosters. Young Rigney availed himself of the opportunity to learn from these older players.

Although he hit only .208 in 1941, Rigney’s numbers for 1942 opened some eyes. He played in 177 games and batted.288. Then World War II intervened. On October 10, 1942, Rigney enlisted in the US Navy, and spent the next three years in the service. He was first stationed in pre-flight at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California, where he met Paula Bruen, a secretary at St. Mary’s. They married in 1944, and were together for 54 years, until Paula died in 1998. They had three children. Bill Jr. (1945-2013) followed his father into baseball and was named Double-A Executive of the Year by The Sporting News in 1979 when he was with the Midland Cubs of the Texas League. Bill Sr.’s other children were Tom Rigney (born 1947) and Lynn Rigney Schott (1949). Bill and Paula had six grandchildren.

In 1944 Rigney was at the Alameda (California) Naval Air Station preparing to be sent to the Mariana Islands when his commodore, very much the baseball fan, found another position for him. He spent 1945 playing the infield for his unit’s baseball team.

While Rigney was in the Navy, the New York Giants in 1943 purchased his contract from Oakland in exchange for Dolph Camilli (who was to be the Oaks’ player-manager). He was discharged on November 12, 1945, and signed an $8,500 contract for 1946. When he arrived in New York after spring training in Arizona, it was for the very first time. Like many ballplayers of his and prior eras, he played in the first major-league game he saw. It took place on April 16, Opening Day, against the Philadelphia Phillies at the Polo Grounds. The 28-year-old Rigney played shortstop and led off. In 1998 he told writer George Will he had hoped that “If there’s a God in heaven, let someone quickly hit a ball to me and get it over with.”3 His first fielding chance came when Skeeter Newsome slammed a grounder in his direction. He made the play and thought, “I may be all right up here.”4 He struck out on an Oscar Judd 3-and-2 screwball in his first at-bat. Two batters later, Mel Ott put the Giants in the lead with a two-run homer. It was the 511th and last home run of Ott’s career. Rigney had two hits and scored a run in the 8-4 Giants win.

In each of his first four seasons with the Giants, Rigney played at least 100 games, The infielder split his time between shortstop and third base in his first year, starting 69 games at third and 29 games at shortstop. His best season was 1947, when he batted .267 with 17 home runs and 59 runs batted in, in a career-high 130 games. His 17 homers were part of a Giants barrage that set a major-league home-run record of 221. (The record was later broken.) In 1947 he played 71 of his 129 starts at second base, and in 1948, playing 105 games at the keystone sack, he led the National League with 18 errors at the position. It took Rigney some time to get used to the position. A half-century later he told a writer that in his first five double plays as a second baseman, he hadn’t “tagged the bag right once, on any of the five.”5

One of Rigney’s favorite stories about his time with the Giants involved Johnny Mize. The two were roommates. Mize was very much into keeping fit and worked his way into shape by running in a rubber suit. After each workout, he would wring out the sweat from the suit and exclaim, “Now that’s a workout!” Mize enjoyed a drink or two after a game. When Rigney told Mize that the scotch would mix in with the sweat, Johnny scoffed at the suggestion. In August 1947, while Mize’s back was turned, trainer Doc Bowman squirted some lighter fluid into his recently wrung-out perspiration. When Mize returned, Rigney said, “Let’s do a test.” Bowman took a match and put it to the perspiration. After the minor explosion, Mize said, “I had better cut back on my drinking.” Rigney eventually let Mize in on the joke, and the Big Cat was not particularly pleased.6

Rigney’s Giants were not faring well on the playing field. In his rookie season the team (61-93) finished last in the National League. The team had been seriously damaged by the raids of the Mexican League, losing nine players, including pitcher Sal Maglie.7 After acquiring several sluggers in the offseason, the team rebounded for a fourth-place finish in 1947, but had virtually no pitching to complement the offense that produced 221 homers. They also displayed little speed, stealing only 29 bases.

The Giants were treading water in 1948 when the likeable Mel Ott was replaced by Leo Durocher 76 games into the season. Rigney played well enough to be selected for the All-Star Game. For the year, he batted .264 with 10 homers and 43 RBIs. His home-run count was down as Durocher encouraged him to hit the ball to all fields and stop trying to pull it over the short porch in left field.8 Under Durocher, the team went 41-38 to finish out the 1948 season, but the new manager was looking to shake things up.

In 1949 Rigney, splitting his time mostly between second base and shortstop, hit a career-high .278 with 6 home runs and 47 RBIs in 122 games, but the Giants dropped to 73-81. Durocher agreed when Rigney said, “At this time, I’m the only guy on the Giants who plays the game the way Leo wants it to be played. I’m the only one.”9

A year later, Rigney would not be the only one. The 1950 Giants underwent a series of changes that propelled them to third place and put Rigney on the bench. Al Dark and Eddie Stanky were acquired from the Boston Braves for shortstop and second base. Henry Thompson played third base. Rigney came to bat only 83 times and batted .181.

“Of course I was upset,” Rigney said. “I had just had a good year and was a solid player, but all of a sudden, I got caught without a position. I thought of asking to be moved because I knew I could still play, but being a Giant was part of my life. I wanted to end up a Giant. Only in 1950 did I think about what I’d do after my career ended. I paid special attention to how the game was played because I had nothing else to do.”10

The Giants’ pitching also got a big boost that season when Sal Maglie, who had been suspended for jumping to the Mexican League in 1946, was allowed to return. Then pitcher Jim Hearn was acquired, giving the Giants three quality starters (Maglie, Hearn, and Larry Jansen). And the changes were to continue. Early in 1951 the Giants brought up Willie Mays from Minneapolis, setting in motion a series of changes, and by the time the dust had settled, Bobby Thomson was at third base, Monte Irvin in left field, Don Mueller in right field, and Whitey Lockman at first base. Rigney respected Durocher’s job as manager in 1951. “He brought us back and he wouldn’t let us quit,” Bill said. “I learned an awful lot about managing from him that year. Hey, we’re still in this thing, come on.” Rigney got the managing bug that season and it wouldn’t be long until he had a team of his own.11

On August 9, 1951, after the Dodgers had swept a three-game series from the Giants to take a commanding 12½-game lead, Jackie Robinson came into the Giants’ clubhouse and said to Durocher, “Leo, Leo, how do you like it? I can smell Laraine’s perfume all the way in here (the visitors’ clubhouse).” He was referring to actress Laraine Day, who was Durocher’s wife. The Giants could hear Dodger pitcher Ralph Branca singing, “Roll out the barrel, the Giants are on the run. The Giants are done.”12 Rigney would not forget these comments.

The Giants charged into contention with a 16-game winning streak. They won 37 of their last 44 games and faced the Dodgers in a best-of-three playoff. Before the first game, Rigney, Wes Westrum, and Lockman walked up behind the batting cage while Robinson was taking his swings and said, “Jackie, turn around, you’ll never guess who’s here.”13

Rigney spent most of 1951 on the bench, batting .232 in 69 at-bats. But between June 22 and July 15, he started 13 games, and had 12 hits in 48 at-bats. The Giants won eight of the games.

Down the stretch, the team pulled together. “Guys were helping each other out so much, it was unbelievable,” Rigney recalled. “We were still making errors, throwing to the wrong base, that kind of thing, but instead of getting on the culprit, or giving him the silent treatment, everyone else would sort of swarm around him and shower him with encouragement and love.”14

In the climactic third game of the playoff with the Dodgers, Rigney pinch-hit for catcher Wes Westrum with the Giants trailing 4-1 in the bottom of the eighth. Teammate Eddie Stanky had told him that Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe was tiring, but Rigney stuck out and the next two batters were retired as well.

In the bottom of the ninth, singles by Al Dark and Don Mueller put runners at first and second. Whitey Lockman doubled. Dark scored but Mueller twisted his ankle arriving at third and went down. Rigney was one of those who helped Mueller to the clubhouse in deep center field.15

“I was in the clubhouse looking out the window at the field when Thomson hit the pennant-winning three-run-homer off Branca,” he recalled. “They were just two marvelous teams. There was such quality and I was proud to be part of it.”16

Rigney pinch-hit for Hank Thompson in Game Two of the World Series against the Yankees with one out in the top of the seventh, the bases loaded, and the Giants trailing Yankees southpaw Eddie Lopat, 2-0. Urged by Durocher not to hit into a double play, 17 Rigney hit a fly ball to right that was corralled by Hank Bauer on the warning track. Monte Irvin scored from third, and it was the Giants’ only score as the Yankees won, 3-1. Rigney batted foiur times, each time as a pinch-hitter. His only hit came in Game Six when he singled in the seventh inning, but was left stranded as the Yanks won 4-3, to win the Series.

During the next two seasons Rigney again spent most of his time on the bench, being more observer than participant and grooming himself for the next stage of his career. He batted .300 in 1952 in 90 at-bats. The following season, he saw even less action, coming to the plate only 20 times and having five hits to show for his efforts. That was the end of Rigney’s major-league playing career. In eight years, he had batted .259 with 41 homers and 212 RBIs.

“I left the club to go off and be a player-manager for Minneapolis. Leo asked me to stay with the Giants and coach, but I said, ‘I’ve got to tell you: I can’t because I want your job.’ He replied, ‘Go off and manage and someday you’ll get it.’”18

In 1954, managing the Giants’ top farm club, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, he led the team to a 78-73 record and a third-place finish. In 1955 the team swept to the pennant with a 92-62 record. Robert Creamer wrote in Sports Illustrated, “Despite travail and frustration that might have felled a lesser man, he led his team through a spectacular season. He got them off to a fast start and took a firm grip on first place. But the parent Giants, off to a slow start, took a firm grip on some of Rigney’s best players and brought them up to reinforce New York’s roster. Injuries compounded the felony and the Millers tripped, stumbled and fell to fifth place in midseason. Then the Giants gave Rigney Monte Irvin. The Millers rallied round, ran off 15 straight to move back to first place and raced on to win the pennant by eight full games and swept past the postseason playoffs and into the Little World Series.”19

Rigney’s success in Minneapolis, coupled with the widely held belief that Leo Durocher was through, fed rumors that Rigney would succeed Durocher. Then owner Horace Stoneham called, offered him the job, and Rigney took it. He managed the Giants during their last two years at the Polo Grounds. The team he inherited was aging and its 67 victories in 1956 were the lowest since 1946, Rigney’s rookie year. Rigney was different from his predecessor in many ways, particularly in his relationship with the team’s star, Willie Mays. James Hirsch, in his biography of Mays, wrote, “Rigney wanted to establish his own authority, to create a different culture (from Durocher), so he vowed to treat all players the same.” Rigney even went so far as to say “If anyone can show me enough to move out Willie, Alvin (Dark), or Don (Mueller), even those spots may not be safe.”20 This approach did not sit well with Mays, and when Rigney criticized him publicly, not privately as Durocher had, a rift formed between the two.

In 1957 Rigney reconciled with his star, and Mays had a great season. Rigney came to realize that Mays needed a father figure, a role favored by Durocher. Rigney said, “If I had to do it over again, I think I might have been a little more active in his life.”21

The Giants were in sixth place. But Rigney refused to give up, always seeking the edge. In August he was vocal in blasting umpires for calling players out although the fielders’ feet were off the bag on plays at first and forces at second. In his typical style, Rigney said, “I thought of taking movies of Gil Hodges playing first to prove how often he’s off the bag when he takes a throw – but, what would be the use? The umpires would say they haven’t any time to watch movies.”22

In the Giants’ last home game at the Polo Grounds, on September 29, 1957, Rigney started as many members of the Giants’ 1954 championship team as he could field, seven in all. Most of them would not be prominent after 1957, but Bill Rigney was going home to the Bay Area.

As manager of the New San Francisco Giants, Rigney had several new faces that had spent the prior season on the farm. Orlando Cepeda, Jim Davenport, Willie Kirkland, and Bob Schmidt joined the Giants and brought San Francisco into pennant contention during their first two years in Seals Stadium. In 1959 the team led the league by 3½ games in late August, but dropped 18 of their last 29 games to finish in third place, three games behind the Dodgers. That collapse put Rigney’s job in jeopardy.

In June 1960 the Giants were in second place with a 33-25 record, four games behind the league-leading Pirates. However, they had lost eight of 12 games, including three straight at home to the Pirates, and Horace Stoneham, who held Rigney responsible for the prior year’s collapse, fired his manager. For the balance of the season, Rigney and everyone else could only look on in dismay as the Giants, under interim manager Tom Sheehan, finished at 79-75, slipping to fifth place, 16 games behind the Pirates.

Rigney was not out of work long. The expansion Los Angeles Angels hired him as their first manager and he was with them from 1961 until he was fired during the 1969 season. In 1961, the Angels defied the experts, winning 70 games and finishing eighth in the ten-team American League. Had it not been for a bad start (they lost eight in a row after winning their opener), things might have been even better. The team lost 30 games by one run and 26 by two runs. They were so close to something special, but defensive lapses stood in the way. “We kicked away too many games with mental and physical errors,” Rigney said. “We went to sleep on the bases. We threw to the wrong base far too many times, thereby giving the opposition a run or two runs they didn’t deserve. I will be terribly disappointed if we lead both leagues in errors again.”23

The expansion cast of misfits and castoffs did have fun, and Rigney, sometimes unwittingly, joined in. Veteran pitcher Art Fowler once tried to sneak up and give Rigney a hot foot at a team meeting. Rigney caught him, spit on Fowler and said, “The meeting’s over.”24 Rigney was prone to ulcers during this time and clubhouse man Tommy Ferguson would prepare pound cake and milk for the skipper. The treat, however, did not always get to the skipper. One time Earl Averill took a couple of bites from the cake and sipped some milk. Those on the bench broke into laughter.

Rigney’s times with the Angels were good years. In 1962 the team almost did the impossible. The Angels got off to a good start and had great team spirit. Playing the Yankees in New York on May 22, the Angels had won four straight to pull within two games of the league-leading Bronx Bombers. Through nine innings the teams were tied, 1-1. Rigney had his pitchers (he used four in all) issue seven intentional walks including an American League-record four to Roger Maris, before Elston Howard’s sacrifice fly drove in Joe Pepitone with the game-winner in the 12th inning.

The Angels sailed into July not only in contention, but at the top of the heap. On July 4, after a four-game winning streak, they stood in first place with a 45-34 record, a half-game ahead of the Yankees and the Cleveland Indians. It was a veritable dogfight with nine of the league’s ten clubs within ten games of one another. Rigney was lauded for his mastery of the bullpen as 11 different pitchers saved games during the course of the year. Braven Dyer chronicled the Angels that season and his words in the July 14 issue of The Sporting News summed up the essence of the team’s and Rigney’s success: “Come along for the ride.”

As Rigney himself said, “Until you’ve taken a ride on the team bus with these guys, you just can’t believe them. Their spirit is so infectious, you just can’t act normal around them. If you’re with them, you are one of them. There’s no halfway mark. Either you’re in or you’re out. They kid each other unmercifully, not only about their playing, but about anything that lends itself to levity. Sure, it’s done on other clubs. But I’ve never seen anything like the way they do it or even heard of anything like it before. The value of it, of course, is that it keeps everything loose. All of us know people who go through life without ever learning to relax properly. They ought to take a bus ride with my men. It’d shake ’em up good.”25

The Angels took their record to an astounding 18 games above .500 (82-64) on September 11 to sit in second place, four games behind the Yanks. That was as close as they would get, slipping to third in the late going. Nevertheless, the upstart Angels held everyone’s interest for the bulk of the season and Rigney garnered the American League Manager of the Year Award.

Rigney was fired 39 games into the 1969 season. The team had lost ten straight games and was in last place with an 11-28 record. His overall record with the Angels was 625-707. After the 1962 season, the team under his leadership never again reached those heights. Late in the 1969 season, Rigney returned to the Giants, this time helping out with their radio broadcasts, joining announcers Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons. But his stay in the announcing booth was temporary, as he was anxious to manage again.

Rigney returned to the Twin Cities in 1970 and guided the Twins to their second consecutive Western Division championship. They lost in the League Championship Series to Baltimore, and would not return to the postseason for 17 years. The 1970 Twins had a potent lineup with Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, and Cesar Tovar leading the way. The pitching staff was headed by Jim Perry who went 24-12 en route to the Cy Young Award, and Ron Perranoski who had a league-leading 34 saves. However, the team had a number of key injuries along the way. Pitcher Luis Tiant spent two months on the disabled list, and Rod Carew’s broken leg put him and his .376 batting average on the shelf on June 22. He didn’t return for three months.26 Rigney spent two more years with the Twins before he was fired midway through the 1972 season.

In 1973 Rigney returned to the Bay Area and joined the Oakland A’s front office. The A’s of that time were owned by the temperamental Charlie Finley. Late in the season, Rigney was told to scout the Orioles for the postseason playoffs. When he took time off to spend time with his ailing wife, Finley fired him.27

After coaching with the Padres in 1975, Rigney returned to the Giants as manager in 1976 at the behest of new owner Bob Lurie, but managed for only that one season. The team went 74-88. Rigney continued in baseball. He scouted for the Angels through 1981 and rejoined the A’s as special assistant to the president in 1982. In 1993 he was with the A’s during spring training and crossed paths with George Will, who eloquently summed up the essence of Bill Rigney in his book Bunts:

“Rigney is a pleasant face of a sport that too often turns to the public only the flinty face of avarice. Rigney is a reminder that mind as well as money matters in a game chock-full of telling details. Rigney is a keeper of the flame. He understands this paradox: Each player’s dignity is enlarged because each player is a small part of a long and lengthening tradition of craftsmanship and companionship across the generations.”28

In his early years in Oakland with its new ownership, Rigney was very much involved with the decision-making process, and nary an important decision was made without his input. During his tenure which, on occasion, took him to the broadcast booth, manager Tony LaRussa and general manager Sandy Alderson relied on him for knowledge and advice.

Rigney was with the A’s for 20 years, and was still with them when he died from cancer on February 20, 2001. He was 83 years old.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Bitker, Steve, The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ’58 (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 2001).

Graham, Frank, The New York Giants (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952).

Hensler, Paul, The American League in Transition, 1965-1975 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2013).

Hirsch, James, Willie Mays, The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010).

Hynd, Noel, The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants (New York: Doubleday, 1988).

Peary, Danny, We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era – 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Random House, 2006).

Vincent, Fay, ed., We Would Have Played for Nothing: Baseball Stars of the 1950’s and 1960’s Talk About the Game They Loved. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008).

Will, George, Bunts: Curt Flood, Camden Yards, Pete Rose, and other Reflections on Baseball (New York: Scribner, 1998).

Will, George, Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball (New York: Macmillan, 1990).

Bush, Dave, and Dwight Chapin, “It Musta Been Rigged: Bill Rigney, Dead at 83, Lived a Charmed Life in Baseball,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 21, 2001.

Creamer, Robert, “Leo Durocher is No Longer Manager of the Giants,” Sports Illustrated, October 3, 1955.

Dyer, Braven, “Rigney Haunted by Memory of Record in Close Games,” The Sporting News, January 27, 1962.

Dyer, Braven, “Chesty Cherbus Spreading Wings for Fast A.L. Flight,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1962.

Robinson, Murray, “Rigney Charges Umps Give Outs with Fielder Off Bag,” New York Journal-American, August 6, 1957.

Ward, Alan, “Oak Notes from Visalia,” Oakland Tribune, March 10, 1939, 34.

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

Oakland Tribune

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

Baseball-Reference.com

NewspaperArchive.com

ProQuest

Interview with Tom Rigney (Bill Rigney’s younger son). January 3, 2014.

Interview with Earl Averill. January 9, 2014.

Notes

1 Bill Rigney, quoted in Fay Vincent, ed., We Would Have Played for Nothing, 37.

2 Alan Ward, Oakland Tribune, March 10, 1939.

3 George Will, Bunts, 236-238.

4 Vincent, 40.

5 Steve Bitker, The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ’58, ’62.

6 Danny Peary, We Played the Game, 27.

7 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants, 336-337.

8 Peary, 67.

9 Peary, 93.

10 Peary, 118-119.

11 Vincent, 45.

12 Vincent, 44.

13 Vincent, 46.

14 James Hirsch, Willie Mays, The Life, The Legend, 129.

15 Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green, 209.

16 Peary, 154.

17 Peary, 177.

18 Peary, 224.

19 Robert Creamer, Sports Illustrated, October 3, 1955.

20 Hirsch, 252.

21 Hirsch, 257.

22 Murray Robinson, “Rigney Charges Umps Give Outs with Fielder Off Bag,” New York Journal-American, August 6, 1957, 7.

23 Dyer, The Sporting News, January 27, 1962.

24 Peary, 515.

25 Dyer, July 14, 1962.

26 Paul Hensler, The American League in Transition, 1965-1975, 78-81.

27 Hensler, 201.

28 Will, Bunts, 239.

Full Name

William Joseph Rigney

Born

January 29, 1918 at Alameda, CA (USA)

Died

February 20, 2001 at Walnut Creek, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.