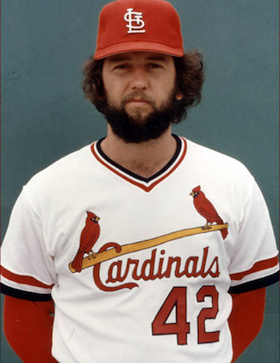

Bruce Sutter

Imagine you’re standing at the plate. You see the pitch coming toward you and you think that you’re gonna knock the snot out of that sucker. You swing with everything you have and you hit … air. Congratulations! Bruce Sutter just got you with his split-fingered fastball.

Imagine you’re standing at the plate. You see the pitch coming toward you and you think that you’re gonna knock the snot out of that sucker. You swing with everything you have and you hit … air. Congratulations! Bruce Sutter just got you with his split-fingered fastball.

The split-fingered fastball moves toward the plate as if it’s rolling along a table. It heads on a beeline when all of a sudden the bottom falls out of it, you feel like an idiot, and the catcher is laughing. The pitch not only saved what had been a moribund career, it propelled Sutter to 300 career saves and a one-way ticket to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Howard Bruce Sutter was born on January 8, 1953 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the fifth of six children born to Howard and Thelma Sutter. His strange and circuitous route to the majors began at Donegal High School in Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, where he excelled at basketball and football as well as baseball.

The old Washington Senators drafted him as a 17-year-old when he graduated high school. The problem was, they thought he was 18 and the rules prevented them from talking to him until he was old enough to vote. They never made him an offer, so he enrolled at Old Dominion University, where he found his academic career faced one major problem – he didn’t like to study. He quit school and went back to Lancaster and played semipro ball with Hippey’s Raiders of the Lebanon Valley League, where Chicago Cubs scout Ralph DiLullo saw him pitch. DiLullo, who had a lifelong dream of signing a Hall of Famer, signed him to a free agent contract on September 9, 1971, for $500 a month with a $500 signing bonus.1

Sutter’s professional career was almost over before it got started when he suffered a pinched nerve in his elbow after only two games and five innings with the Cubs’ affiliate in the rookie level Gulf Coast League. He returned to Lancaster and worked in a plant that did the printing for cigar boxes, and had elbow surgery at his own expense. He didn’t tell the Cubs because he was afraid they would cut him.

When he arrived at spring training in 1973, Sutter discovered he no longer had a fastball. Then, as if he were starring in a corny movie, he started working with minor league pitching instructor Fred Martin, who taught him the pitch that made his career. Martin had spent 17 seasons in the minors, but played for the Cardinals in 1946 and 1949-50, compiling a 12-3 lifetime major league record. He had used the split-fingered as a way of changing speeds on a hitter. A common pitch today, no one was using it in the majors at the time Martin taught Sutter how to throw it.

Of course, learning to throw a pitch and mastering it are two different things. Sutter spent 1973 with the Quincy Cubs of the Class A Midwest League, and while his career didn’t hit the stratosphere immediately, his ERA did; it was over 6.00 early in the season as he learned to control the split-fingered fastball. He finished the year with a 3-3 record and a 4.13 ERA. Walt Dixon, Sutter’s manager in the rookie league and at Quincy, wasn’t overly confident in Sutter’s potential.

“When Bruce Sutter is ready for the big leagues, that’s the day the Communists take over,” he reported to the Cubs’ minor league staff.2

The Cubs, however, started Sutter with the Class A Key West Conchs in 1974. The Conchs were a dreadful team that finished the season with a 37-94 won-lost record. Sutter was 1-5 in 18 games (one start), but he was getting the hang of the split-fingered fastball; he had an excellent 1.35 ERA and was promoted part way through the season to the Midland Cubs – managed by Dixon — of the AA Texas League. In eight appearances there, including one start, he went 1-2 and posted a 1.44 ERA. Dixon may have started brushing off his copy of Das Kapital by this time.

It was clear that Sutter was on his way. He got off to a hot start for Midland in 1975, going 2-0 with 12 straight scoreless innings to start the season. For the year, he went 5-7 with a 2.15 ERA in 41 appearances, all in relief, including 13 saves.

The 1976 Cubs were a bad outfit with an awful pitching staff. Sutter could have made the big club, but began instead with the Wichita Aeros of the AAA American Association. The Cubs needed pitching help and decided that Sutter, who was already 2-1 with a 1.50 ERA in 12 innings, would be more valuable in Illinois than Kansas.

Sutter made his first appearance on May 9 in the last game of a five-game losing streak, during which the Cubs gave up 14 runs in a game three times. He threw the final inning of a 14-2 loss to the Cincinnati Reds, giving up two hits but no runs and striking out one batter. He got his first major league save on May 31 in a 7-5 win over Pittsburgh, and his first big league victory in a 5-3 win over San Francisco on July 9. Although the Cubs finished with a 75-87 record, Sutter had a fine rookie year, going 6-3 with 10 saves and a 2.70 ERA.

Sutter didn’t suffer a sophomore jinx in 1977. In fact, his absence proved how crucial his presence was to the team’s success. Unlike the previous season, the 1977 Cubs were contenders.

On August 2 they were 62-42, with a 2 1/2 game lead on the Phillies. Unfortunately, that was also the day Sutter went on the 21-day disabled list with a shoulder strain. Between that date and August 26, when Sutter made his first appearance since coming off the DL, the Cubs went 9-14 and were 7 ½ games off the pace. They never recovered and finished at 81-81, 20 games out.

Sutter, nonetheless, had a masterful season. He went 7-3, with a 1.34 ERA and 31 saves. He was voted the National League Pitcher of the Month for May, and was selected to the National League All-Star team, although he did not play due to his shoulder problem.

The Cubs began 1978 as if it was the 1977 season all over again, building up a 2-and-a-half-game lead in the National League East Division by June 21. The descent began earlier this time, and the team couldn’t lay blame on a Sutter injury.

He got off to another excellent start, earning 14 saves by the All-Star break, and was named to the National League team for the Classic, which was played in San Diego. The Senior Circuit had won 15 of the previous 17 encounters with their American League counterparts, so they didn’t panic when they were down 3-0 early in the third inning before coming back to win 7-3. Sutter earned the victory, pitching a perfect 1 2/3 innings. He also reflected his temporary teammates’ cockiness about their early three-run deficit.

“We were three runs behind and that made the game even,” he said.3

Sutter earned his 22nd save of the season on August 7 to go with a 7-3 record; the Cubs, meanwhile, were still in the hunt with a 57-53 record, 3 1/2 games behind Philadelphia. He then slumped badly, to the point where the team brought in Sutter’s personal guru, Martin, to help him get some bite back into his bread-and-butter pitch. Martin decided that Sutter was overworked.

“His ball is dropping, but not as sharp as it used to,” Martin said. “There’s nothing wrong with him physically that a little rest wouldn’t cure. We just need a few complete games from our starters.”4

Those complete games didn’t come, as Sutter went 1-7 with five saves from August 7 on. For the year he was 8-10 with 27 saves and a 3.19 ERA. Another promising season for the Cubs went down in flames as they finished 79-83, 11 games off the pace.

Some people, in addition to Martin, thought Sutter’s mediocre second-half numbers resulted from overwork. Sutter disagreed. “Last year [1978] it was said that, as the Cubs’ only dependable reliever, he wilted from overwork in August and September,” wrote Ron Fimrite. “Sutter denies this, insisting that it was just a late slump.”5

Sutter began the 1979 season with some questions hanging over him. Would he return to his earlier form? How would he handle not having access to Martin, who became pitching coach of the crosstown White Sox? He answered those questions, all right, in spades. He tied what was then the major league record for saves in a season with 37 (set in 1972 by Clay Carroll of the Cincinnati Reds and tied in 1978 by Rollie Fingers of the San Diego Padres), and went 6-6 with a 2.22 ERA in 101.1 innings pitched. About the only black mark on his season came on May 17 when he gave up a home run to Mike Schmidt of the Phillies in the 10th inning to give the Phillies a 23-22 victory. Those numbers were good enough to make him the third reliever to win the Cy Young Award.6

The “what can you do for an encore” pressure that Sutter faced going into the 1980 season was intensified by the fact that he won a then-record $700,000 contract in arbitration. Despite the high-for-its-time salary, Sutter wanted a long-term contract, and told reporters he might not show up when training camp opened. It turned out to be an empty threat as he was in uniform on the first day of workouts February 27.

“Sutter indicated he didn’t mean what he said when he issued his threat not to pitch in spring training,” wrote the Associated Press. “He told Bob Kennedy, club vice-president, as much while making peace with him prior to the workout.”7

The Cubs did their fans a favor in 1980 by not even making a pretense of being in the pennant race. In 1979 they were ½ game out as late as July 27. The 1980 Cubs were a disaster, finishing in the National League East basement with a 64-98 record. Sutter was one of the team’s few bright spots; he led the league with 28 saves, and although he had a 5-8 won-lost record, his ERA was an excellent 2.64. He also earned the save in the All-Star Game, pitching two innings of perfect relief as the National League defeated the American League yet again, this time by a 4-2 score at Dodger Stadium.

After the season, a trade that was a long time in the making was finally consummated. The Cardinals had tried to obtain Sutter since before the season began. General manager Whitey Herzog finally succeeded at the winter meetings in Dallas, sending first baseman Leon Durham, outfielder Ken Reitz and a player to be named later (Ty Waller) to the Cubs for Sutter.

In obtaining Sutter, the Cards got a reliever who had more saves by himself in 1980 (28) than the entire Cardinals bullpen (27). They also eliminated a personal nemesis; five of Sutter’s saves came against St. Louis. Those facts helped convince St. Louis to sign him to a four-year contract.

Did signing Sutter make a difference in the Cards’ fortunes? Yes … and no. Their feeble bullpen had contributed to a 74-88 record in 1980, and St. Louis did have the best overall record in the National League East in 1981. The problem was there was a strike in the middle of the season, and when play resumed, Major League Baseball decided to split the season in half, with teams resuming the schedule as if there had been no break. Because the Cardinals had played one less game than the Montreal Expos after the strike, and had no way of making it up, they ended up ½ game behind Montreal in the second-half standings; despite their overall 59-43 record.

Nobody could blame Sutter. He performed as advertised, leading the league in saves for the third year in a row with 25, to go with a 3-5 record and 2.62 ERA. He also saved the All-Star Game for the National League. No doubt the results of 1981 were disappointing for St. Louis. However, it’s the knocks of life that make the successes all the sweeter, as Sutter and his teammates found out in 1982.

In 1982 Sutter experienced something for the first time – a season-long pennant race. And he made the most of it, leading the league in saves for the fourth straight year with 36, while compiling a 9-8 record with a 2.90 ERA. After two victories and two saves in his previous four All-Star Game appearances, he missed the 1982 classic in Montreal because of a pulled groin muscle.

If Sutter had anything left to prove, it was how he performed in the clutch. That September he went 1-2, but saved six games, including a September 14 showdown with the second-place Phillies where he induced the dangerous Schmidt to bounce into a one-out double play in the eighth with the bases loaded to preserve a 2-0 lead. Oh, and guess who got the save in the division-clinching game, a 4-2 win over Montreal on September 27?

Sutter had a memorable National League Championship Series (NLCS) as the Cardinals swept West Division champion Atlanta in three straight games. He got the night off as Bob Forsch went all the way in a 7-0 St. Louis win. He had an interesting perch from which to watch a controversial decision by Atlanta manager Joe Torre. The Cardinals had David Green on second base with the score tied 3-3 in the bottom of the ninth and one out. The batter was Ken Oberkfell, who was 6-for-10 lifetime against Atlanta pitcher Gene Garber and Sutter was on deck. Walking Garber would have forced Cardinals’ manager Whitey Herzog to pinch-hit for Sutter and get him out of the game. Torre decided to pitch to Oberkfell, who was 7-for-11 after the at-bat with a game-winning single.

After Sutter saved the National League pennant-clincher, Herzog was asked to compare the 1982 Cardinals against the Kanas City Royals teams he managed in the 1970s that lost three classic League Championship Series to the New York Yankees 1976-78.

“This is a younger club and I don’t think it’s as intelligent as those Kansas City teams,” Herzog said. “But we’ve got Sutter. We [the Royals] didn’t have that big guy in the bullpen over there.”8

The 1982 World Series pitted the Cardinals against the Milwaukee Brewers, who were nicknamed “Harvey’s Wallbangers” after their manager Harvey Kuenn and their propensity for banging outfield walls with line drives. After the Brewers lived up to their reputation in Game One with a 10-0 smacking, Sutter pitched two scoreless innings for the victory as the Cardinals won the second game, 5-4, on a bases loaded walk in the bottom of the eighth.

Sutter got the save in Game Three, even though it was not one of his better outings. He came into the game with two out in the seventh and the Cards comfortably ahead, 5-0. A two-out walk to Robin Yount in the eighth and a two-run shot by Cecil Cooper started some sweating in the St. Louis dugout, but they got that run back in the top of the next inning. Sutter had a routine ninth – the only baserunner reached first on an error – and the save was his.

The Series see-sawed back and forth without Sutter appearing in Games Four, Five or Six. In Game Seven, Joaquin Andujar left after seven solid innings with a 4-3 lead. Sutter retired the side in order in the eighth, and got a little breathing room when the Cards scored two more runs to pad the lead.

Sutter induced two groundouts in the ninth, then faced Gorman Thomas, who had no plans of going down without a fight. Thomas worked Sutter to a 3-2 count, then fouled off three pitches before finally swinging at strike three and getting out of the way as the pandemonium of victory ensued.

The National League East was a weak division in 1983 as the contenders, Montreal, Philadelphia, St. Louis and Pittsburgh all hovered around the .500 mark. The Cardinals were ½ game off the lead as late as September 5 with a 69-67 record. Unfortunately they went 10-16 the rest of the way, finishing fourth with a 79-83 record.

Sutter was not the dominant pitcher he had been in earlier years. He wasn’t chosen for the All-Star team, which was particularly difficult because his own manager, Herzog, was doing the picking. The snub was understandable, as he had only seven saves by the mid-season break. Sutter sought out his old pitching coach from the Cubs, Mike Roarke, for advice. Roarke came down from his home in Rhode Island to help, and observed that Sutter’s split-fingered fastball was traveling too … fast?

“The ideal speed is 78 or 79 miles an hour,” Sutter said. “I was throwing it over 80. When I throw it hard, it just won’t break.”9

The advice worked as Sutter was much better in the second half, getting 14 more saves. His other numbers weren’t as good – a 9-10 won-lost record and a 4.23 ERA, the highest of his career to that point.

Just as Victor Kiam liked Remington Shavers so much he bought the company, the Cardinals liked Roarke’s work with Sutter so much that they hired him as pitching coach for the 1984 season. It’s hard to quantify how a coach affects a team, but the pitching staff as a whole showed marginal improvement, as team ERA improved from 3.79 in 1983 (10th in the National League), to 3.58 (seventh) in ’84.

For Sutter, Roarke’s hiring seemed like a godsend, as he made it clear from the get-go that he was back. He recorded four saves in six appearances during the first two weeks of the season, while not allowing a run in 10 2/3 innings. Contrast that with 1983, when he didn’t record his fourth save until May 26. He had 21 saves by the All-Star break and made the team, although he didn’t appear in the game, which the National League won 3-1 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco.

“He’s getting his first pitch over,” noted Pirates manager Chuck Tanner in comparing the 1984 Sutter to the 1983 version. “Last year he was falling behind the hitters. This year he’s Bruce Sutter again.”10

Bruce kept on being Bruce as the season progressed, managing to avoid the slumps he had experienced in previous seasons. He broke the National League single season saves record on September 3 when he notched his 38th. The next target was the new major league record of 45 set in 1983 by Dan Quisenberry of the Kansas City Royals. He tied Quisenberry’s record in the Cardinals’ 160th game, a 10-inning 4-1 victory over, ironically, the Cubs. The Cubs hammered St. Louis 9-5 in the next game, so Sutter wasn’t used. Then came the final game of the season.

The Cubs had clinched the division before the series even began, so nothing was on the line except personal accomplishments. Sutter entered the game in the eighth to protect a 1-0 lead for teammate Rick Ownbey. Sutter retired the Cubs in order in the eighth and needed three outs to break the record.

Unfortunately, he didn’t get them. Three singles, a walk and an error led to two runs, a blown save and a loss to end the best year of Sutter’s career. Besides tying the save record, he set a personal high for appearances with 71, and innings pitched, with 122 2/3. He also had a 5-7 won-lost record and a 1.54 ERA.

Sutter could not have picked a better time to have a career year because he became a free agent after the season and there would be no shortage of, well, suitors bidding for his services. Ted Turner and his Atlanta Braves signed him to a contract that was amazing, not just for the amount of money involved but for the way it was structured. The contract called for $4.8 million over six years, tame by 21st century standards but impressive for its time, plus an additional $4.8 million that would be invested in a deferred payment account at 13 percent interest that would pay him $1.3 million annually for 30 years after the six-year contract ended. All told, he would be paid an estimated $44 million over the next 36 years.

Early in the 1985 season it looked like he might be worth the money; he had nine saves by the end of May, compared to 12 saves at the same time in 1984. But he hit a rough patch at the beginning of June, giving up nine earned runs over 12 innings in five appearances; he also blew three saves during the month.

By August he was trying to pitch despite shoulder inflammation. On August 31 he went to St. Louis for a cortisone injection from Cardinals’ team physician Dr. Stan London. The shot helped early in the month as he had three saves by September 15, but with the season a washout (the Braves went 66-96), the team shut him down for the year after a September 18 appearance in a 7-3 loss to Cincinnati.

Sutter underwent surgery for a pinched nerve in his shoulder on December 13 and while he was back for spring training, it was clear that the surgery did not bring him back to his old form. He appeared in 16 games in 1986, with a 2-0 record, three saves, three blown saves and a 4.34 ERA. By the end of May, the Braves were using Gene Garber and Paul Assenmacher in the closer role, as they could no longer rely on Sutter. They placed him on the disabled list on June 1, and he was out for the remainder of the 1986 season and all of 1987.

He returned for 1988, but his first appearance that year was an indication that the clock was winding down on his career, as he blew a two-run lead in the ninth against the Cubs in a game that the Braves eventually lost 10-9 in 13 innings. Things didn’t improve much after that; he appeared in only 38 games and earned 14 saves with a 1-4 record and a 4.74 ERA. He finished with a flourish, earning his 300th career save on September 9 in a 5-4 Braves victory over San Diego.

Sutter stayed in the Atlanta area after his career ended with his wife Jayme Leigh and their three sons. He received baseball’s two ultimate honors in the early 2000s. The Cardinals “retired” his number 42 in 2006. Technically, the number had already been set aside by all of Major League Baseball in tribute to Jackie Robinson, but the Cardinals added his name to Jackie’s in the retired number display at Busch Stadium.

He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, becoming the first pitcher admitted to the Hall who had never started a game in the majors. Sadly, DiLullo didn’t live to see his dream fulfilled; he died in 1999.

Sutter died at the age of 69 on October 13, 2022.

Sources

http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/

The Cardinals Encyclopedia, by Mike Eisenbath

Los Angeles Times

San Antonio Express

http://www.pitchandhitclub.org

Dixon Evening Telegraph

The New York Times

The Index-Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina)

http://stlouis.cardinals.mlb.com

1 DiLullo was a great scout. He signed Joe Niekro and urged the Cubs to sign Sandy Koufax.

2 Jim Kaplan, “The Week {July 10-16], Sports Illustrated, July 25, 1977.

3 Associated Press, “NL stars never thought they were behind,” Southern Illinoisian, July 12, 1978.

4 Associated Press, “Cubs fading” Ottawa Citizen, September 6, 1978.

5 Ron Fimrite, “This Pitch in Time Saves Nine,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1979.

6 The previous winners were Mike Marshall of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1974 and Sparky Lyle of the New York Yankees in 1977.

7 Associated Press, “Sutter shows despite threat of slowdown,” Southern Illinoisan, February 28, 1980.

8 Associated Press “Cardinals headed to World Series,” The Daily Pantagraph, October 11, 1982.

9 Herm Weiskopf, “Inside Pitch [Through July 31], Sports Illustrated, August 8, 1983.

10 Associated Press, “Cards keep spelling relief S-U-T-T-E-R,” The Sunday Pantagraph, (Bloomington, Illinois), July 29, 1984.

Full Name

Howard Bruce Sutter

Born

January 8, 1953 at Lancaster, PA (USA)

Died

October 13, 2022 at Cartersville, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.