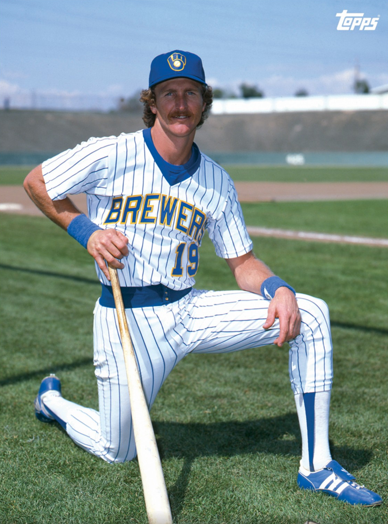

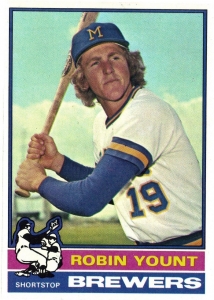

Robin Yount

If any player could be called Mr. Brewer it is Robin Yount. He played his entire 20-year major-league career with the Milwaukee Brewers, debuting as an 18-year-old shortstop in 1974, and helped reinvigorate and re-energize a fan base that had been reeling since the Braves abandoned Milwaukee for Atlanta in 1966. Yount led the Brewers to their first AL pennant, in 1982, and that season became the second Brewer to be named league MVP. Two years later he underwent career-threatening shoulder and arm surgeries, switched positions to center field, and was named MVP again, in 1989. The 17th member of the exclusive 3,000-hit club, Yount was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

If any player could be called Mr. Brewer it is Robin Yount. He played his entire 20-year major-league career with the Milwaukee Brewers, debuting as an 18-year-old shortstop in 1974, and helped reinvigorate and re-energize a fan base that had been reeling since the Braves abandoned Milwaukee for Atlanta in 1966. Yount led the Brewers to their first AL pennant, in 1982, and that season became the second Brewer to be named league MVP. Two years later he underwent career-threatening shoulder and arm surgeries, switched positions to center field, and was named MVP again, in 1989. The 17th member of the exclusive 3,000-hit club, Yount was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

Yount endeared himself to Brewers fans and teammates because of his all-out hustle, humble nature, and team-first attitude. “Part of the reason I played as hard as I did,” he said years after retiring, “was because I didn’t want to embarrass myself. If you’re fearless, sometimes you get careless, and that’s when mistakes happened.”1 Yount never changed that style, even when he was nearing the end of his career. “He runs out every groundball to the pitcher as hard as he can,” said teammate B.J. Surhoff about the 34-year-old in 1990. “He is the best baserunner in baseball, he plays hitters perfectly, he’s an incredible clutch hitter, he gives himself for the team at all personal costs. When you play with him, you realize that he plays the game on the edge.”2

At 6-feet tall and just 165 pounds, Yount certainly did not have the physical build of a power hitter, yet was surprisingly muscular and quick, both with the bat and on his feet. He developed surprising power as he matured, spanking 20-plus home runs in a season on four occasions. He was a natural spray hitter and took advantage of the powers alleys to collect doubles, hitting at least 40 in four seasons, and 30-plus eight times, and triples, racking up double figures four times. Yount had a closed stance and gripped the bat in an unorthodox style; instead of lining up the knuckles of his forefingers and and pinky on the bat as most right-handed hitters do, his hands were slightly twisted, the left hand clockwise and the right hand counterclockwise. “Nobody else looks quite like Robin Yount in the batter’s box,” observed sportswriter Gary D’Amato. “He has a distinctive stance; his right foot drawn back, left heel off the ground, left toe pointed in, crouched low.”3

“My swing was certainly not the prettiest thing I’ve ever seen, even though it worked for me,” Yount told ESPN The Magazine. “I had very few mechanical thoughts. … I was strictly a reaction hitter. I would let the ball get as deep on me as I could, try to recognize it as early as I could, and … I tried to hit it as hard as I possibly could.”4 Said knuckleballer Charlie Hough of Yount, “He doesn’t have the type of swing you would teach. It’s a very unorthodox style. He actually looks like he’s tied up, but just when you think you have him beat, he gets the bat head out there for a single or double down the line.”5

Milwaukee sportswriter Tom Flaherty described Yount as “the most modest superstar in sports.”6 Shy, quiet, and unassuming by nature, Yount was a club leader who led by example and deed, and not by a rah-rah attitude. He kept his teammates loose with his relaxed approach and humor, and willingly let them take the spotlight. “Publicity? I don’t especially like it,” he quipped as an 18-year-old rookie, “but I understand there is a need for it in baseball.”7 As he developed into star and MVP, reporters always flocked to him for interviews, but Yount was never good with sound bites. About the 1982 World Series and his record-setting hitting, he retorted, “If there is a drawback, I suppose it would be all the exposure.”8

Robin R. Yount was born on September 16, 1955, in Danville, Illinois, just over the state line from where his parents, Phil and Marion Yount, lived in Covington, Indiana. Within a year of Robin’s birth, the elder Yount relocated the family, which also included his older brothers Jim and Larry, to the affluent community of Woodland Hills, in the San Fernando Valley about 25 miles northwest of Los Angeles. An aerospace engineer, he began a job with Rocketdyne, a division of Rockwell International.9

A precocious youngster, Robin was always small for his age, yet a gifted athlete with myriad interests. By the age of nine, he began golfing and two years later was racing motorcycles, two passions that remained constant throughout his life. At Taft High School he played basketball and football, though he abandoned them after his sophomore year to concentrate on baseball. He initially pursued it with a certain nonchalance, unlike his brother Larry, five years older, who was an acclaimed pitcher and was selected by the Houston Astros in the fifth round of the 1968 amateur draft. Robin’s attitude to baseball became more serious in the summer of 1972, after his junior year, when he moved to Oklahoma City to live with his brother, who was playing for the 89ers of the Triple-A American Association. “That exposed me to the professional life,” explained Yount years later. “I lived it — went to the park early, hit, took grounders, hung around the clubhouse, hung out with the guys.”10

Aided by a noticeable growth spurt, the 6-foot, slightly-built yet sinewy 165-pound Yount emerged as a star in his senior year. That spring dozens of scouts followed the hard-hitting shortstop, who with a stellar .455 batting average led his team to the West Valley League championship.11 He was named the league’s Co-MVP, as well as All-Los Angeles City Player of Year.12 Just days after graduating, the 17-year-old Yount was selected by the Milwaukee Brewers, on scout Gordon Goldsberry’s recommendation, with the third overall pick in the 1973 amateur draft, after the top selections, pitcher David Clyde and catcher John Stearns.13 Two decades later, the longtime veteran talent evaluator Goldsberry still considered Yount “the best athlete I’ve ever been associated with.”14 Yount withdrew his letter of intent to play baseball at Arizona State University15 and signed with the Brewers, accepting an estimated $75,000 bonus.16

The Brewers assigned Yount to the Newark (New York) Co-Pilots in the short-season Single-A New York-Penn League. The club was atrocious, winning just 15 of 70 games, but Yount was its bright spot, batting .285, earning All-Star honors at shortstop and being named the league’s player most likely to reach the majors.

Yount was invited as a non-roster player to the Brewers spring training in Sun City, Arizona, in 1974. The club was coming off its fourth consecutive miserable season in Milwaukee since relocating from Seattle and changing its name from the Pilots after its inaugural season in 1969. Skipper Del Crandall initially gave little thought to Yount making the club, not just because he had only 64 games of A-ball under his belt; but also because Yount had made 18 errors in those games, plus the shortstop spot seemed to be secure on club with Tim Johnson making 135 starts in his rookie season in 1973. But Yount proved that he was no ordinary 18-year-old big-league wannabe. He impressed the staff as much with his physical prowess as with his mental toughness.

“Some people are always worrying about what just happened, and that makes them unprepared for what happens next,” quipped Crandall, himself a former 11-time All-Star catcher. “Others, like Robin, have the ability always to concentrate on what’s coming up next.”17 Unfazed by Yount’s smooth transition to the speed and cerebral aspects of game was Goldsberry, noting, “One reason Robin adapted to the major leagues at age 18 was that he had been exposed to professional ball by Larry. Robin had worked out with Triple-A players and had seen that he could do all the things they could do.”18

As the Brewers’ roster was gradually trimmed during camp, Robin was briefly reunited with Larry who was traded to the club on March 30. While Larry was ultimately cut, Robin was named the starting shortstop and debuted as the majors’ youngest player on April 5 against the Boston Red Sox at County Stadium. Surprisingly relaxed, Yount claimed he felt no pressure to perform. “I had nothing to lose,” he said years later. “If I didn’t play well, they would send me back to the minor leagues which was probably where I belonged anyway.”19 Batting ninth, Yount drew a walk off Luis Tiant in his first at-bat and flied out to left field in his other plate appearance before he was lifted for pinch-hitter Felipe Alou.

Hitless in his first 10 at-bats, Yount singled off Baltimore’s Dave McNally on April 12 in Milwaukee for his first hit. The next day he went from goat to hero in a matter of minutes. His error on Bobby Grich’s grounder enabled the Orioles to tie the game, 2-2, in the top of the eighth. Moments later, Yount led off the bottom of the frame by smashing his first home run, off starter Ross Grimsley, to give the Brewers the lead and eventual victory, 3-2. Yount seemed overwhelmed by big-league pitching early in the season, with his batting average under .200 through May 11; however, he proved his mettle, collecting 18 hits in 49 at-bats (.367 average) from May 12 through May 31 to secure his position on the field, which he didn’t relinquish for the next 20 years.

“I don’t think about how scared I should be because I’m in the major leagues at 18,” Yount told sportswriter Pat Jordan for his Sports Illustrated feature in 1974. “I just go out and play. When I’m at bat I concentrate on hitting the ball, and when I’m in the field I concentrate on picking it up.”20 By early August, Yount’s mobility was becoming compromised by tendinitis in his feet, a malady that ultimately shelved his season after August 17. Praised by Brewers beat reporter Lou Chapman as “display[ing] the poise and ability of a Marty Marion,” Yount’s totals (3 HRs, 26 RBIs, .250 batting average, .276 on-base percentage, and .346 slugging average) belied what his future foretold.21

Cast into national spotlight as a teenager, hailed as the next superstar, and dubbed “the Kid,” Yount handled the psychological pressure to perform and the demands of the press. “I can’t worry about how old I am,” he said, deflecting questions about his age. “There are too many other things to think about.”22 Some of that pressure subsided in 1975, when the Brewers acquired Henry Aaron from the Atlanta Braves. Yount got off to a hot start, batting .386 and slugging .649 to be named the AL Player of the Month in April, but a severely sprained ankle on the artificial turf in Kansas City sidelined him for two weeks in May, and he never regained that form. In an era when shortstops weren’t expected to produce offensively, Yount exceeded expectations (8-52-.267) and played in 147 games to finish with 256 games played as a teenager, which ranked second in major-league history, behind the Chicago Cubs’ Phil Cavarretta’s 277 (1934-1936).23

Yount was praised for his range at shortstop and his strong arm. “He’s got Mark] Belanger’s lateral rhythm,” said Chicago White Sox coach Al Monchak, comparing Yount to the Orioles fielding whiz. “He’s always in control of his body. He moves backward after flies better than any young player I’ve ever seen.”24 Nonetheless, Yount was still learning the position and suffered a setback in ’75, committing the most errors (44) of any player in baseball; consequently, he participated in the Brewers’ Arizona Fall Instructional League.

In 1976 Yount revealed his fiercely independent streak, foreshadowing a bigger confrontation two years later. Empowered by arbitrator Peter Seitz’s ruling that major-league players could become free agents by playing out their option, Yount threatened to play the entire season without a contract to test his market value, though he did report to spring training on time.25 He eventually signed a two-year pact in late April.26 Durable, he played all but three innings the entire season, improved his defense (committing 13 fewer errors), and batted in the .280s through July before slumping in July and August to finish with a lackluster .252 average and just a .301 slugging average. By the end of the 1977 season, however, Yount could lay legitimate claim to be the best all-around shortstop in the AL. Emerging offensively, he collected 174 hits and batted .288, both of which ranked second behind Cecil Cooper on the team.

After four years in the big leagues, Yount was sick of losing and playing for an uncompetitive team, which had averaged 92.5 losses per season since his arrival. Even before the 1977 campaign concluded, Brewers players seemed in open revolt against skipper Alex Grammas. “It’s depressing, day in and day, out,” said Cooper about the losing.27 Yount, whose contract was to expire at the end of the season, said, “I can’t say that I’ve enjoyed baseball that much. It’s not as much fun as it should be.”28 The cornerstone and future of the team, Yount considered the players’ attitude to be part of the problem and made it known that he’d like to see the Brewers make substantial on-the-field improvements and commit to winning if he were to sign with the club again. Team owner and President Bud Selig made wholesale changes in the offseason, including hiring Harry Dalton as new GM and George Bamberger as manager, and also signed free agent Larry Hisle, the reigning AL RBI leader, and acquired Ben Oglivie in a trade.

Optimism abounded when the Brewers spring training opened in 1978, with Selig claiming the squad was the best club in franchise history.29 Before camp concluded, Yount was on the DL, away from the team, and actively contemplating retirement. For the second time in three years, he had reported to camp without a contract. He was still unsigned by mid-March, and trade rumors swirled. Adding to the mental stress of his contract situation, Yount was struggling on the diamond, plagued by painful tendinitis in his feet, a recurring problem since his rookie year, and a sore right elbow, hampering his throwing. On March 28 he was placed on the DL, and soon thereafter abruptly left the team.30 Frustrated mentally and physically, Yount contemplated quitting baseball to became a pro golfer. Reactions from sportswriters were diverse: Some criticized Yount for being impetuous and selfish, holding the Brewers hostage with his indecisiveness; while some like Bob Wolf of the Milwaukee Journal were sympathetic at a time when athletes were often portrayed as a spoiled millionaires, opining that Yount is “an unusual young man, one who supposedly is more interested in contentment than money.”31

Looking back on this this period in his life, Yount commented to Robert Creamer, “I’m not very introspective, but I guess I was at an age, 20, 21, 22, when people wonder what they’re going to do with their lives. I suppose I was beginning to wonder if playing baseball was what I wanted to do. I think now it might have been a part of growing up. I was very fortunate. Bud Selig was very patient with me. It’s as though he said, ‘Give the young man all the time he needs to straighten this out.’”32

The 1978 season opened without Yount, his future with the club still cloudy. His absence paved the way for another wunderkind, 21-year-old shortstop Paul Molitor, a non-roster invitee to camp, who like Yount had only 64 games in single-A ball. Molitor had been reassigned during camp, but Yount’s injury and then self-induced exile forced the club to recall the player who was the Brewers starting shortstop on Opening Day. After conversations with Dalton and Selig, Yount returned to the club in May, though he remained unsigned. Not yet ready to play the field and needing extra time to get his arm back in shape, Yount debuted on May 6 by pinch-hitting, then started his first game at shortstop on May 15 (in the club’s 31st game of the season), shifting Molitor to second base.

Yount seemed rejuvenated, batting .315 (17-for-54) in his first 14 starts, as the club went 9-5 to move over .500. The Brewers seemed to fulfill Selig’s prediction, stringing together 10 straight victories to move 10 games over .500 on June 17, though in fourth place in the power-packed AL East. During that stretch, Yount hit the first of his 10 career walk-off home runs, sending the first pitch from the Toronto Blue Jays’ Tom Murphy over the wall to give the Brewers a 5-4 victory, after which his “teammates acted as it were the World Series,” quipped Lou Chapman in the Milwaukee Sentinel, emptying from the dugout.33 “I enjoy playing with this club more than I ever had,” said an elated Yount after his heroics.34

By the end of the month, Yount came to terms with the Brewers, signing a five-year deal, reportedly for in excess of $2.3 million, a hefty increase from his $80,000 salary.35 The contract, negotiated by his brother Larry, who had become a successful real-estate developer, definitively ended the incessant trade speculation buzzing around Yount since his return to the team. It was a new era in Brewers baseball, characterized by a dazzling offense that led the majors with 173 homers, featuring Hisle (34-115-.290) and Gorman Thomas (32-86-.246), and five other players with at least 13 round-trippers.

On September 6 Yount added his name to the home-run bonanza by spanking two for the first of 14 times in his career, victimizing the Blue Jays at Exhibition Stadium, highlighting a 4-for-4 performance with 5 RBIs in a 7-0 shellacking. It was part of the most productive stretch in his career thus far, batting .356 and slugging .546 over 41 games (July 26 to September 7). Despite missing almost one-fifth of the season, Yount had his most productive campaign at the plate (9-71-.293). The Brewers set a team record with 93 wins, finishing in third place, 6½ games behind the New York Yankees.

In 1979 Yount married Michele Edelstein, whom he knew in high school. They welcomed four children into the world in the 1980s, Melissa, Amy, Dustin, and Jenna. He fiercely guarded his family’s privacy and shielded them from media attention. A born competitor, Yount enjoyed living on the edge. “I didn’t play for the love of baseball,” he quipped, “I played for the love of competition.” He had various offseason pursuits, some of which probably made the Brewers’ front office cringe.36 Throughout his baseball career, he raced motorcycles on off-road courses, all-terrain vehicles, and go-carts. He later dabbled in auto racing, once crashing a car in the late 1980s. “I had just bought a new race car, a Sports 2000,” Yount told sportswriter Peter Gammons. “One of the first times I raced it, I took a corner wrong at about 120 and flipped. As I was lying there upside down, I thought, this must not be for me. A brand-new car, and look what I did to it.”37 Yount also fished, hunted, skied, and continued to play golf.

The 23-year-old Yount began his sixth big-league season in 1979 looking for consistency. After a seeming breakout season in 1978, he had regressed the following year, batting .267, with a .308 on-base percentage, while slugging just .371, the second lowest totals among regulars on the club, though all three statistics matched his career averages to that point (.270, .308, and .364). His rising star seemed to have been eclipsed by Molitor, who hit .322 in his sophomore season, and Thomas (who led the AL with 45 home runs). The Brewers bashers, dubbed Bambi’s Bombers in honor of their skipper, George Bamberger, slugged their way to a team-record 95 wins in 1979, the second-best record in the AL, but finished a distant runner-up to the 102-win Orioles.

In the best physical shape of his life, Yount got off to a hot start in 1980 en route to one of the most productive seasons for a shortstop in big-league history. He collected 22 hits in 52 at-bats in a 13-game stretch, from April 12 to April 27, to raise his average to .400. “People would say that I had ‘potential,’” said Yount,” but they never understood that I needed to learn to play the game after a half-season in the minors. It is different when you’re learning in the majors, because everyone sees you, and there isn’t any room for patience. For me, it’s a matter of consistency.”38

On May 4 at Comiskey Park in Chicago, he smashed his first career grand slam in the Brewers’ 11-1 laugher. Yount appeared stronger and more determined. After hitting just 34 home runs in his first six seasons, he walloped his 10th of the campaign on June 14 to set a new personal best. He batted almost exclusively all season long in the two-hole, which afforded him better pitches and more protection; his power numbers soared and his new-found offensive prowess gained him more exposure He was finally selected to his first All-Star Game, as a backup to the starter, weak-hitting Bucky Dent of the Yankees. [Yount went 0-for-2]. On August 16 Yount went 3-for-5 with two doubles, a home run, and four RBIs.

It’s hard to imagine in a sport as obsessed with statistics as baseball, but lost completely on sportswriters at the time was that Yount’s second hit, a double off Sandy Wihtol in the 10-5 drubbing of the Indians at Cleveland Stadium, was the 1,000th base hit of his career, making him the sixth youngest player to reach that milestone, after Ty Cobb, Mel Ott, and Al Kaline, Freddie Lindstrom, and Buddy Lewis. Bambi’s Bashers once again led the majors in home runs, but were sunk by 10 losses in 11 games in the second half of August and ultimately finished in third place (86-76), while their intra-divisonal rivals, the 103-win Yankees and 100-win Orioles, produced the two best records in baseball. Competing in the tough AL East did no team favors in the pre-wild-card era.

In a phenomenal campaign, Yount joined Ernie Banks as the only shortstops in big-league history to collect 80 or more extra-base hits in a season, and became the first AL shortstop to compile more than 300 total bases since 1965 AL MVP Zoilo Versalles of the Minnesota Twins.39 Yount set Brewers records for runs scored (ranking 2nd in the AL with 121) and doubles (a major-league-most 49), while batting .293, slugging .519, and hitting 23 home runs.

Yount’s encore to his phenomenal season seemed like a resounding failure with three weeks to go in the 1981 season, one of the most forgettable in big-league history, yet most memorable in Brewers lore. A strike by the players union (the Major League Baseball Players Association) canceled about one-third of the season, leading owners to divide the season into halves with the “winners” playing one another in a newly established divisional series in order to generate interest for the postseason. The Brewers finished in third in the first half (31-25), and were fading in the second half, having lost five of eight games to fall to third place, 20-16, three games behind the Detroit Tigers on September 14. Just 3½ games separated the top five teams. Yount’s batting average at the time was just .251 with a paltry .295 on-base-percentage and a .389 slugging percentage.

Defying the odds, the Brewers got hot and their pesky shortstop was in the middle of the club’s unlikely march to the first postseason berth in its 13-year history. With the Brewers trailing the Tigers, 6-5, on September 25 in the first game of a pivotal three-game series in Detroit, Yount “salvaged a pennant race,” exclaimed sportswriter Tom Flaherty in the Milwaukee Journal, smashing a dramatic three-run home run off starter Jack Morris to give the Brewers an 8-6 lead.40 The victory pulled the Brewers, piloted by Buck Rodgers, to within a half-game of the Red Sox and Tigers; a loss would have dropped them 2½ back.41 After splitting the next four games, the Brewers pulled into first place with the Tigers on September 30 with a resounding 10-5 victory over the Red Sox at County Stadium. “The team has gradually grown up,” quipped Yount, who led the way with four hits and three runs. “Experience and doing pretty well in pressure situations have given us confidence.”42

The spotlight was set on the final series of the season, a winner-take-all three-game set against the Tigers in Milwaukee. Yount once again supplied the offensive power, going 3-for-4, giving him nine hits in his last 13 at-bats, and knocking in two runs in a thunderous 8-2 shellacking. “I’m not trying to do anything different,” said Yount of his offensive explosion after his season-long struggles. “When you’re hitting good, you don’t think that much.”43

With the Brewers trailing 1-0 in the eighth inning the following night, Yount’s all-out hustle on a routine sacrifice bunt led to the winning run and the second-half championship. After Molitor led off with a walk, Yount laid down a perfect bunt to first baseman Ron Jackson. According to Flaherty, Jackson looked to second, but was unable to make the throw with the speedy Molitor; that delay was costly.44 By the time he threw to shortstop Lou Whitaker covering first, Yount was safe. Four batters later, Yount scored what proved to be the winning run, 2-1, on Thomas’s sacrifice fly. It was the conclusion of the most exciting eight-game stretch thus far in Brewers history, and Yount led the way, collecting 15 hits in 33 at-bats and scoring nine runs, more than compensating for his otherwise disappointing offensive numbers (10-49-.273).

The Brewers faced the Yankees in the ALDS, which surprisingly unfolded as a battle of pitchers instead of sluggers, featuring just 32 combined runs (13 by the Brewers) in the five-game series. The Brewers lost the first two contests at home, then won the next two at Yankee Stadium, to set up another do-or-die game. Yount collected three hits but the Yankees emerged victorious, 7-3. The Brewers batted just .222 collectively, while Yount led the club with six hits and four runs.

The Brewers got off to another sluggish start in 1982, dropping into the AL East cellar on May 31. The next day Rodgers was fired and replaced with Harvey Kuenn. Whereas Rodgers was a nervous type, pacing in the dugout, the 51-year-old Kuenn, who had had a leg amputated two years earlier, was laid back with his atmosphere-changing “Have some fun” mantra.45 The players immediately responded to Kuenn’s style, posting a 30-11 record under his guidance, and moved into first place. Harvey’s Wallbangers, the power-packed lineup that crushed a major-league-most 216 home runs, were born, featuring the Fu Manchu-wearing Gorman Thomas, who tied for the AL-lead with 39 home runs; Ben Oglivie, who smashed 34; the criminally underrated Cecil Cooper (32-121-.313); and Molitor with a major-league-most 136 runs scored; however, no one put on a show like Yount.

Unlike his team, Yount started off the 1982 season red-hot, rapping three hits on Opening Day, and had collected 13 hits in 29 at-bats in his first nine games. While the Brewers clawed their way into contention, trading the top spot in a fierce back-and-forth battle against the Red Sox with the Orioles lurking behind, the 26-year-old Californian surged over a 28-game stretch (June 30 to July 31), batting .410 on 48 hits, including 8 home runs, 24 RBIs, and 32 runs, and was named the AL Player of the Month for July. He became the second Brewer to be selected to consecutive All-Star Games (joining Don Money, 1976-1977), earning the start and going 0-for-3.

It appeared as though the Brewers might run away with the crown, hold a commanding 6½-game lead over the Red Sox on August 27. While the Wallbangers played inconsistently in September, the Orioles surged, at one point winning 30 of 40 games. The two powerhouses played each other seven times in the final 10 games, and as in the previous season, Yount’s bat was decisive. In the first of those games, on September 24 in Milwaukee, Yount’s two home runs and career-best six RBIs propelled the Brewers to a 15-6 thumping. But the Brewers lost the next two to the Orioles and held a precarious one-game lead on October 1 on the eve of a season-defining four-game series in Baltimore to close the season. Skipper Earl Weaver’s bunch slaughtered the Brewers in the first three games, outscoring them 26-7, setting up a dramatic winner-take-all-game on the last day of the season. Yount cracked a first-inning home for the first run of the game and another solo shot in the third, marking the seventh time in the season that he hit two round-trippers in one game. He also added a triple, his career-best 12th, in an electric 3-for-4 performance with four runs scored as Harvey’s Wallbangers strolled to a convincing 10-2 victory. “If there were skeptics around who didn’t believe that Robin Yount was the most valuable player in the American League,” wrote Flaherty in the Journal, “they changed their minds.”46

Yount was a star on a team filled with them, concluding one of the best seasons for a shortstop in baseball history: He became first shortstop to lead the AL in total bases (367) and slugging percentage (.578); only the Chicago Cubs’ Banks and Pittsburgh Pirates’ Honus Wanger had ever accomplished that feat. Yount also paced the circuit with 210 hits and 46 doubles, while clubbing 29 home runs and driving in 114 runs. Yount lost the batting title by one point to the Royals’ Willie Wilson (.332 to .331) in an episode that produced some controversy when skipper Dick Howser sat Wilson on the final day of the season to protect the title.47 “He’s the best all-around shortstop I’ve ever seen,” opined Kuenn, himself a former 10-time All-Star, about Yount.48 Yount received 27 of 28 first-place votes to become the second Brewer to win the league’s MVP Award (Reliever Rollie Fingers was named AL MVP and AL Cy Young Award winner in the strike-shortened 1981 season). He also won his first and only Gold Glove Award, a year after leading the AL in fielding percentage at short.

The Brewers captured their first pennant after a stunning comeback against the California Angels in the ALCS. After losing the first two games in Anaheim, Kuenn’s crew won the next three in Milwaukee. Yount managed only four hits in 16 at-bats without an RBI.

The 1982 World Series featured a contrast in styles: Harvey’s Wallbangers vs. Whitey Ball, the St. Louis Cardinals’ version of small ball and speed, espoused by their skipper Whitey Herzog. The Brewers flipped the script in Game One, relying on 13 singles and just one home run to crush the Redbirds, 10-0, in the Gateway City, led by Molitor’s five hits and Yount’s four. Quiet in Games Two and Three, the Brewers exploded for six runs in the seventh inning of Game Four, including Yount’s checked-swing, bases-loaded two-run single, to win, 7-5, and tied the Series.49

In front of 56,562 screaming fans in Game Five, the third consecutive record-breaking crowd at County Stadium, Yount once again provided the fireworks, becoming the first player in World Series history to record two four-hit games in the same World Series. His home run in the seventh brought a lusty chant of “MVP!” from the crowd, in the Brewers 6-4 victory. A win away from the first world championship for Milwaukee since the Braves won the title in 1957 (they relocated to Atlanta after the 1966 season), the Brewers lost the final two games in St. Louis. Yount went 1-for-8 in those two contests, finishing with a Series-high 12 hits, as well as a team-best six runs and six RBIs (tied with Cooper).

The end came abruptly for Harvey’s Wallbangers, though it was not immediately evident in 1983. Widely expected to win another pennant, the 1983 Brewers were racked by injuries, losing their reigning Cy Young Award winner, 18-game winner Pete Vuckovich, for all but three starts, 1980 Cy Young recipient Rollie Fingers, whose forearm injury forced him to miss the entire ’82 postseason and all of ’83; while Oglivie and Thomas missed significant portions of the season and combined for just 18 home runs, down from 73 the year before. The Brewers struggled to play .500 ball through the first half of the season, then went on a roll, winning 24 of 33. On August 11 Yount went 2-for-4 with two RBIs in the Brewers’ 6-4 win over the Blue Jays to catapult the Brewers into first place, one game ahead of the Tigers, Yankees, and Orioles.

The emotional leader of the team, however, was suffering, plagued by lower back pain since at least the All-Star Game (his third and final), which had forced to him to the bench for several games and into a designated hitter role for a few more. On August 22 he blasted a walk-off solo home run, his first round-tripper in five weeks, in the bottom of the 10th inning to give the Brewers a 3-2 victory, their seventh in eight games, and keep them on top of the East by a half-game. Two days later, he had another walk-off hit, a clutch single with the bases loaded in the 14 against the Angels, but that proved to be one of the last highlights for the Brewers. Two days after that, they began their collapse, losing 18 of 24, including 10 in a row, and finished in fifth place. Their 87 wins marked the club’s sixth consecutive winning season, which they have not matched as of 2020.

Despite back pain, eventually diagnosed as a ruptured disc which would have far-reaching implications in his career, Yount (17-80-.308) finished with a .503 slugging percentage; scored 102 runs, hit 42 doubles; and led the AL with 10 triples. According to one modern metric established well after he retired, Yount was once again the league’s most valuable offensive player, following up his 9.9 oWAR with 7.6 in ’83, though he finished 18th in the MVP voting.50

A turning point for Yount came in 1984 when a series of injuries threatened to derail his career. Two years after winning the pennant, the Brewers finished with the worst record in the AL, (followed by two successive sixth-place finishes in 1985 and 1986). Injuries, aging players, and an unproductive farm system had decimated the club. Just 28 years old, Yount began his 11th big-league season in 1984 still feeling the lingering effects of lower back pain that had zapped his power in the second half of 1983, hitting just four home runs in his final 67 games. By mid-July he began having pain in his right arm and shoulder, making it difficult to throw to first, and was ultimately shifted to DH for most of the final month of the season. A rare bright spot on an awful team, Yount led the club in almost every offensive category, including 16 home runs, as the Brewers hit the fewest in the league, and 105 runs scored.

A month after the conclusion of the regular season, Yount underwent arthroscopic surgery to remove bone spurs in his shoulder and shore up tendons, and was expected to be ready for spring training in 1985. He reported on time, but his shoulder pain remained, making it impossible to play shortstop. Skipper George Bamberger, who had replaced Rene Lachman after one season, moved his inspirational team leader to left field, a position Yount hadn’t played since Little League. “It’s difficult just getting used to the ball. The angle is different,” said Yount, who didn’t complain about the move, though that didn’t make it easier. “It’s a different game. I don’t know if I’d call it boring. There’s a lot of standing around, but there’s plenty for me to think about because I still have to learn the position.”51 A naturally gifted and instinctive athlete, Yount was moved to center field in July to take advantage of his speed, but runners exploited his weak arm, which was limited by pain and required cortisone shots. “The year just became one of those wasted seasons,” said Yount. “Eventually I realized that something had to be done to clean up the shoulder.”52 Yount’s season ended on September 1 and he underwent his second shoulder surgery in less than 10 months to remove bone spurs and calcium deposits.53

Frustrated and concerned, Yount wondered if he’d ever be pain-free or play baseball again after his second invasive procedure. He had already resigned himself to the idea that he would never play shortstop again — and never did, not even an inning — after his last start on September 7, 1984. “If the operation didn’t work, I would have said, ‘It’s been nice,” and would have gone on to other things,” explained Yount the following year. “I love baseball and wanted to keep playing. But I was prepared to leave. I didn’t see myself as a DH.”54

A 13-year veteran at the age of 30, Yount revived his career as a full-time center fielder in 1986. He was pain-free for the first time in almost three years, and it showed at the plate. He didn’t have the power as before, hitting just nine home runs, but he made solid contact, batting a robust .312 (sixth best in the league) mainly from his accustomed two-spot. He made a seamless adjustment to center field, leading all AL outfielders in fielding percentage (.997). “He’s a manager’s dream,” said Bamberger. “Never complains, never wants to sit out, just shows up every day and plays.”55 Propelled by 12 hits in his previous six games, Yount became the seventh youngest player in big-league history (following Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, Ott, Aaron, Joe Medwick, and Jimmie Foxx) to collect 2,000 hits when he singled against the Indians at County Stadium on September 6. “Robin has never changed in all the years I’ve known him,” said coach Larry Haney. “I’ve only seen a couple of players in my 19 years in the game that I haven’t seen dog it at least once, Robin’s one of them.”56

Beginning in 1987, Yount enjoyed the most productive three-year stretch in his career, culminating with his second MVP award in 1989 as a 33-year-old in his 16th season. He played in 480 of 486 games, collected at least 190 hits each season, and twice knocked in at least 100 runs. On April 15, 1987, Yount made arguably the most memorable defensive play in his career, diving to snag a flyball from the Orioles Eddie Murray to preserve Juan Nieves’s no-hitter, the first in franchise history, as part of the Brewers’ major-league record-tying 13 consecutive wins to start the season.57 After an early-season lead in the division, the Brewers lost 12 straight, falling well off the front-running Tigers and Blue Jays, and finished in third place (91-71).58 In 1988 the Brewers played below .500 before ending the season on a torrid 22-9 streak, to finish in third place again, two games behind the Red Sox.

The Brewers finished with an 81-81 record and in fourth place in 1989, which unfolded as a magical year for Yount. Five days after collecting his 2,500th hit in a 3-for-5 performance with a home run and five RBIs in the Brewers’ 10-2 drubbing of the Yankees in New York, Yount was feted at County Stadium on Robin Yount Day on July 7. “The attention, I don’t need it,” quipped Yount in his typical modest fashion. “I’m just a human being with the ability to play baseball. I’m nothing special.”59 In his first at-bat against the Orioles, Yount delighted the County Stadium faithful by hitting a homer. Always appreciative of the support he received from fans, Yount brushed off his accomplishments. “You can’t play the game without recognition, but statistics just aren’t what make me go,” he said. “I enjoy the competition.”60 And competing he was. The day after his career-longest 19-game hitting streak ended, Yount raked the 200th home run of his career and 13th of the season in the Brewers’ 6-1 victory over the Indians in Milwaukee on July 31. That blast put an exclamation point on an especially productive month (40-for-101, 22 runs, 5 home runs, 24 RBIs in 26 games) garnering him the AL Player of the Month Award. In a surprisingly weak division, the Brewers moved to within a half-game of the first-place Orioles on August 20, but struggled thereafter, finishing with a .500 record and in fourth place. Praised by sportswriter Dennis Punzel for “almost singlehandedly [leading] the Brewers from the depth of despair into contention,” Yount became the first player in AL history to be named MVP who did not play for a winning team and just the third player in major-league history to win MVP awards at different positions (following Hank Greenberg and Stan Musial).61 In a tight four-man vote in a year with no truly dominating player in the AL, Yount collected eight of the 28 first-place votes. Judged by one modern metric (WAR), sportswriters made the right decision as Yount (21-103-.318) led the AL in offensive WAR for the third time in his career (7.3) and ranked in the top five of many offensive categories, including third in slugging percentage (.511) and second in total bases (314).

Declared a free agent after the season, Yount expressed his desire to play for a winner and consequently tested his market value. His brother Larry handled negotiations with several teams, including the Angels, Dodgers, Cubs, Royals, and Blue Jays, but in the end, the decision was easy. Yount re-signed with the Brewers, inking a three-year deal in mid-December for reportedly $9.6 million, making him the highest-paid player in baseball in 1990 ($3.2 million). “Bud Selig was a big part of the reason for staying,” Yount told sportswriter Peter Gammons. “Milwaukee’s been a big part of the reason I’ve had some success. It’s small, without a ton of media attention, and it’s easier to play there than in a big media town. It’s a family city. I can go to the park, play, come home, and be with my family. The kids are very happy in our neighborhood.”62

In his final four seasons (1990-1993), Yount experienced a pronounced decline in production while the Brewers competed for the division crown just once. During this stretch, Yount batted between .247 and .264, slugged as high as .390, and had a .330 cumulative on-base percentage; however, he remained healthy, averaging 141 games per season. “I’ve been just good enough to keep my name in the lineup — never too good and never too bad,” Yount told Los Angeles sportswriter Ross Newhan in September 1992, as he approached his monumental 3,000th hit. “It’s a game of streaks, but my strength … is consistency.”63 On September 9 in front of a capacity crowd of 47,589 at County Stadium, Yount stepped into the batter’s box against the Indians reliever Jose Mesa. The Brewers legendary radio announcer Bob Uecker made the call, “One strike on him. Back against Mesa, who is working from the windup. The 0-and-1 pitch. Swings and there it is! A base hit into right-center. He’s done it! Three thousand for Robin!”64 At 36 years of age, Yount became the third youngest (after Cobb and Aaron) and the 17th player to reach the coveted milestone.

Yount signed a one-year contract to return for his 20th and final season with the Brewers, in 1993. His Hall of Fame bona fides were secure: 2,856 games, 3,142 hits, 1,632 runs, 583 doubles, 126 triples, and 251 home runs. He batted .285, slugged .430, and had a .342 on-base percentage. Remarkably consistent, Yount produced a .288/.347/.435 line at home in County Stadium; and .283/.338/.425 on the road; against right-handed pitching (.285/.337/.430) and against southpaws (.286/.354/.429). Yount’s importance to the Brewers, his loyalty to the team and its fan base, however, transcended his statistics. “Robin is what the Brewers stand for,” said Bud Selig. “He’s perfect for this franchise. He’s a great player, but also a great person.”65

In one of the most widely anticipated Hall of Fame elections with three other extremely popular and sure-bet Hall of Fame players, Nolan Ryan, George Brett, and Carlton Fisk, also in their first year of eligibility, there was some doubt whether Yount would receive the required 75% of the vote. He did (77.5%) and joined Brett (98.2%), and Ryan (98.8%) as the triumphant trio of the class of 1999. (Fisk received 66.4% of the vote, and was elected the following year with 79.6%.)

As he was during his playing career, Yount kept a low profile after hanging up his spikes. He resided with his family in the Phoenix area, where he had lived in the offseason for much of his playing career. Yount never lost his desire to compete and continued riding motorcycles and racing cars. He also coached some Little League ball; his son Dustin was chosen by the Baltimore Orioles in the ninth round of the 2001 amateur draft. (He played eight seasons, rising as high as Double A.)

The most famous player in Brewers history, Yount maintained a close relationship to the club. By 1996 he was back at spring training with the Brewers, serving as an assistant, helping players with hitting and throwing batting practice. Though he harbored no intention to manage, Yount felt the tug to put on a major-league uniform and the ideal situation arose. In 2002 he joined the defending World Series champion Arizona Diamondbacks, serving as skipper Bob Brenly’s first-base coach for two seasons. In two separate seasons Yount was back in a Brewers uniform as bench coach: in 2006 on Ned Yost’s staff and in 2008 with Yost and Dale Sveum, both of whom were former teammates of his. After that he continued to work with the Brewers during spring training and act as an ambassador of sorts for Brewers baseball.

In 2012 Yount was part of an ownership group, which included Bob Uecker, for the expansion Lakeshore Chinooks, an amateur collegiate team in Mequon, Wisconsin, of the Northwoods summer league.

As of 2019, Michele and Robin Yount resided in both greater Milwaukee and the Phoenix area.

Last revised: June 9, 2020

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, the online archives via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Peter Gammons, “3 of a Kind,” ESPN The Magazine, February 2, 1989: 94.

2 Peter Gammons, “Forever a Kid,” Sports Illustrated, April 30, 1990. https://si.com/vault/1990/04/30/121905/forever-a-kid-robin-yount-has-mvp-talents-worth-millions-but-revels-in-high-risk-fun-with-very-big-toys.

3 Gary D’Amato, “Yount’s Slashing Swing Not Class, but It Works,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1989: 4.

4 Gammons, “3 of a Kind,” 98.

5 Joe Bierig and Bruce Levine, “Robin, the Boyish Wonder,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1992: 11.

6 Tom Flaherty, “Dead? No! Champions? Yes,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1982: 22.

7 Milton Richman, UPI, “ ‘The Kid’ Robin Yount Not Worried About Age,” The World (Coos Bay, Oregon), May 14, 1974: 16,

8 Dale Hofmann, “Winning, Not Record, Counts — Yount,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11, 1982: III, 1.

9 Robert W. Creamer, “This Robin’s a Rare Bird,” Sports Illustrated, September 27, 1982. si.com/vault/1982/09/27/625002/this-robin-is-a-rare-bird.

10 Peter Gammons, “Forever a Kid.”

11 “Taft’s Chamberlain, Yount Share Award in West Valley,” Van Nuys (California) News, June 15, 1973: 62.

12 “Taft’s ‘Finest’ Robin Yount Named 1973 City Baseball Player of the Year,” Valley News, June 19, 1973: 46.

13 The 1973 draft proved to be historic, producing three Hall of Famers: Robin Yount; third-round pick Eddie Murray (Baltimore Orioles) and Dave Winfield, chosen after Yount, with the fourth pick in the first round by the San Diego Padres. Only two other drafts (as of 2019) produced at least three Hall of Fame players 1971 (George Brett, Jim Rice, and Mike Schmidt) and 1985 (Randy Johnson, Barry Larkin, and John Smoltz).

14 Gammons, “Forever a Kid.”

15 “Texas Pitcher First Pick,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1973: III, 7.

16 Susan Shemanske, “Yount: a Winner All the Way,” The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), September 1, 1992: journaltimes.com/sports/yount-a-winner-all-the-way/article_45612bbb-26c2-592d-9279-9ec3d9c2a7ba.html.

17 Pat Jordan, “Years Ahead of His Time,” Sports Illustrated, July 29, 1974. si.com/vault/1974/07/29/616164/years-ahead-of-his-time.

18 Gammons, “Forever a Kid.”

19 Tom Flaherty, “The Kid. Yount’s Love for the Game Never Grows Old,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1982: 6.

20 Jordan.

21 Lou Chapman, “Brewers Get Glad Tiding; Yount’s Foot Good as New,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1974: 58.

22 Richman.

23 Prior to Cavarretta, Mel Ott held the record of 241 set from 1926-1928 with the New York Giants.

24 Jordan.

25 Associated Press, “Robin Considers Playing Out His Option,” Lacrosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, March 12, 1976: 8.

26 Associated Press, “Yount Signs,” Daily Tribune (Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin), April 21, 1976: 8.

27 Lou Chapman. “Brewers Players Gripe … They’re Sick of Losing,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1977: 16.

28 Ibid.

29 Lou Chapman, “’78 Brewers Best in Club History, Selig Says,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1978: 54.

30 Associated Press, “Yount Put on Disabled List,” Stevens Point (Wisconsin) Journal, April 3, 1981: 13.

31 Matthew J. Prigge, When Robin Yount Almost Quit,” Shepherd Express (Milwaukee), December 14, 2015. shepherdexpress.com/sports/brew-crew-confidential/robin-yount-almost-quit/.

32 Creamer.

33 Lou Chapman, “Yount’s Homer Caps Big Day,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 12, 1978: III, 1.

34 Ibid.

35 Murray Chass, “Suddenly Millionaires Are a Dime a Dozen,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1979: 31.

36 Gammons, “3 of a Kind,” 98.

37 Gammons, “Forever a Kid.”

38 Peter Gammons, “Yount, Mature at 24, Reaching Potential,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1980: 12.

39 Since Versalles’ feat, as of 2018 only one shortstop in the majors had exceeded 300 total bases in a season before Yount did it: The St. Louis Cardinals Garry Templeton had 308 in 1979.

40 Tom Flaherty, “Brewers Still in Contention, Thanks to Yount,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 26, 1981: 1.

41 After games of September 25, the Red Sox and Tigers were both 26-18; Brewers 26-19; the Orioles 1½ back at 24-19.

42 Bob Wolf, “Yount’s Hits Spark Drive,” Milwaukee Journal, October 1, 1982: 4.

43 Don Kausler Jr., “Brewers Need One More Win,” October 3, 1981: II, 1.

44 Tom Flaherty, “Celebration! Brewers Win Title,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1981: 21.

45 Tom Flaherty, “Brewers Having a Blast,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1982: 3.

46 Tom Flaherty, “Dead? No! Champions? Yes.”

47 Howser’s decision to bench Wilson on the last day of the season was just the tip of the iceberg in a smoldering controversy. When news reached Kansas City that Yount had gone 3-for-4 and was about to come to the plate in the ninth, Howser contrived to stop action in his game against the Oakland A’s and had even been in contact with A’s manager Billy Martin for help. Howser hurriedly called Wilson to get ready to pinch-hit while Martin visited the mound to stall, even though his hurler Dave Beard, was not in trouble. It proved for naught as Yount was hit by a pitch, leaving him at .331, a point behind Wilson, who returned to the bench. See “Yount Almost Gets a Batting Title,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1982: 22

48 Kevin Horrigan, “Cards Analyze Loss: ‘That’s Baseball,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 17, 1982: 1F.

49 Ibid.

50 WAR: Wins Above Replacement is an attempt by the sabermetric community to quantify a player’s contributions in the total number of wins he provides in comparison to a replacement player.

51 Tom Flaherty, “Yount Playing Left Like an Old Pro,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1986: 18.

52 Paul Attner, “Robin Rebounds with a Flourish,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1985: 8.

53 Ken Picking, “Yount to stay in center,” Wausau (Wisconsin) Daily News, September 4, 1985: 7.

54 Attner.

55 Ibid.

56 “Yount Singles for Hit No. 2,000,” Milwaukee Journal, September 7, 1986: 9C.

57 The Atlanta Braves opened the 1982 season with 13 victories.

58 The Brewers started the season with 13 straight and were 20-3 before losing 12 straight games and 18 of 20, after which they played about .500 ball the remainder of the season.

59 Gary Reinmuth, “Yount Not Counting Hits,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1989: B1.

60 Ibid.

61 Dennis Punzel, “Yount’s Play Recalls ’82 Season,” Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), August 1, 1989: 13.

62 Gammons, “Forever a Kid.”

63 Ross Newhan, “Hitting His Stride,” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1992: C1.

64 “How Bob Uecker Called No. 3,000,” Milwaukee Journal, September 10, 1992: C5.

65 Attner.

Full Name

Robin R. Yount

Born

September 16, 1955 at Danville, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.