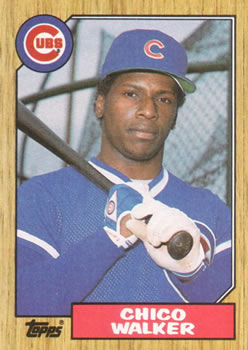

Chico Walker

Chico Walker once told Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons, “Getting to the big leagues wasn’t the problem. But staying in the big leagues was.”1 Walker epitomized the utility man in baseball. From his major-league debut in 1980 through 1993, he played for four different teams, in both leagues, over 11 seasons.2 Yet it took until 1991, at age 32, for him to spend a full year at the top level.

Chico Walker once told Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons, “Getting to the big leagues wasn’t the problem. But staying in the big leagues was.”1 Walker epitomized the utility man in baseball. From his major-league debut in 1980 through 1993, he played for four different teams, in both leagues, over 11 seasons.2 Yet it took until 1991, at age 32, for him to spend a full year at the top level.

Thanks to his athletic ability and strong right arm, he played frequently at each of five different positions in the field:122 games at third base, 88 in left field, 74 at second base, 66 in center, and 42 in right. The switch-hitter was the DH in eight games (all in 1980) and pinch-hit 214 times. A speedy runner and good base stealer, he was used as a pinch-runner in 24 games.

Two definitions of “utility” in Merriam-Webster are: “fitness for some purpose or worth to some end,” and “something useful or designed for use.” Clearly, Walker was of utility to many professional ball clubs over many years. He played 15 seasons in the minors, mainly in the outfield (804 games) but also at second base (526), shortstop (122), and third (90). He also played winters in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela before wrapping up his career in Mexican League ball in 1994.

In a sense, being branded as a utility man may have hurt his career, since he rarely had the opportunity to show what he could do as a regular player. In 1992, Mets batting instructor Tom McCraw said, “He could always hit, but a hitter needs time. You’ve got to give a young guy 30 days, then maybe a day off if he’s struggling, then 15 more. Chico didn’t get that. He got the label part-time player and he has been shortchanged, because anyone in that category is more of a help to the manager to fill gaps.”3 His manager that year, Jeff Torborg, pretty much concurred: “I’d rather not have to play him every day. I like him coming off the bench. But you couldn’t ask any more of the guy than what he’s done. Every club needs a guy who is versatile, especially in this league with all the double moves.”4

Cleotha Walker was born in Jackson, Mississippi, on November 26, 1957.5 His parents were Dorothy Walker and William Walker. “Chico” was a nickname he got at an early age. “Real early,” as he recalled in a 2020 interview. “I went to school with a lot of Hispanic kids. In Spanish, Chico has some reference in being small. I was small [he eventually reached 5-foot-9 and 170 pounds], but I could do a lot of things — run fast, play baseball, basketball, and football. That’s where the nickname came about.”

Walker had five brothers and three sisters. “I’m the middle child. My mother worked for a company that made strings for guitars. My father was a construction worker.” The family moved from Mississippi to Chicago when Chico was around 10 years old. “I think that time in the mid- to late ’60s, a lot of African Americans were migrating from the South to the North. There were better opportunities in terms of work.” It was suggested that racial discrimination might be less of a problem as well. “Right. Outside of Mississippi.”6

Only one younger brother showed particular interest in sports. “He played a little bit in high school, but it didn’t go beyond that.” His own interest in baseball simply came from playing it when young. “Playing it from an early age, I fell in love with the game. I think that’s how it happens with most kids, with whatever sport they play. If you fall in love with something, you just stay after it.”

Chico had already played in both of Chicago’s major-league ballparks before he even got to high school. At age 12, he’d hit a home run at Comiskey and he’d also played at Wrigley, both times in Little League championship games.7

He attended Tilden High School, on the south side of Chicago. The Tilden High School Blue Devils were one of the city’s solid high school teams. They lost to Steinmetz in the Public League playoffs in 1975, though shortstop Walker singled and scored in the final game. “In the finals, we were overconfident. Cocky. We actually thought we had it in the bag, but you’ve got to go out and play the game, right?”

Walker was scouted by Boston Red Sox scout Chuck Koney, selected by the Sox in the 22nd round of the June 1976 amateur draft, and signed on June 15.8 He remembered and appreciated Koney. “What a great, great, great guy. He’s passed away now. What a great guy. He was around all the time.”

Walker’s first assignment was to the Elmira Pioneers, where he played in 1976 (22 games) and 1977 (64 games), all but one game at second base. He had something of a breakthrough season in 1978, batting .279 in 133 games for the Single-A Winter Haven Red Sox, 110 of them at shortstop. His 1979 was spent in Double A with the Bristol (Connecticut) Red Sox, playing second base and batting .265 with eight homers and 57 runs batted in over 123 games. Over the winter, he played ball in Venezuela.

Walker was advanced to Triple A in 1980 and played his first of five seasons for the Pawtucket Red Sox, He spent most of his time at second base in 1980. He played 139 games — mostly at second base, Getting off to a strong start, he hit .272 with eight homers and 52 RBIs. He also stole 21 bases.9 He earned himself a look in the big leagues, and when the rosters expanded in September, he got the call.

Asked about bringing him up earlier, when the Sox had a need in the first half of July, Boston manager Don Zimmer said he definitely would not. “He’s not a polished player yet and needs the work. If I take him up here all he’s going to do is sit for six weeks and what good will that do? He’s a good prospect and he has to play every day.”10

Those years weren’t an easy time to try to break in with the Red Sox. That had something to do with him being tried out at different positions. The outfield had Jim Rice, Fred Lynn, and Dwight Evans. The infield had a number of solid players as well. Reflecting years later, he said, “I could run. I could throw. [But] it was tough to break through…As it turns out, later on in my career my athletic ability helped me to stay in the big leagues a few more years.”

Walker got his feet wet in the majors on September 2, coming in to play second base in the top of the ninth with Boston leading the Angels, 10-2. Rod Carew hit a ball that Walker turned into a 4-6-3 double play. His next appearance was five days later against Seattle. This was a lopsided game in the other direction, with the Mariners leading, 11-1, after four innings. He took over for Dave Stapleton at second base. After walking and grounding out, leading off the bottom of the eighth against reliever Manny Sarmiento, he homered over the bullpen into the right-center field seats. “I always dreamed my first hit would be a homer,” he said, “I didn’t see it go over the fence, though. I didn’t know until I rounded second.”11

The home run came in a game that left little else to cheer for, and the Fenway fans had chanted “Chi-co! Chi-co!” Over the next couple of weeks, he became “the people’s choice.”12 In his next five at-bats (over the course of four games), he hit safely each time. He stood in the batter’s box at Yankee Stadium on September 20 and saw that his average read .857. “Can I catch George Brett?” he joked.13

He was kept busy, appearing in 19 games in September, accumulating 66 plate appearances with five runs batted in and a .211 average. These included all of his career outings as a DH. In 48 fielding chances, he committed two errors.

Walker was disappointed not to make the Boston team out of spring training in 1981, but it did give him an unforgettable experience in Pawtucket — along with teammates including Wade Boggs, Marty Barrett, and Rich Gedman. On April 19, with one out in the bottom of the ninth inning, Walker doubled off the center-field wall, moved to third on a wild pitch, then (on a sacrifice fly) scored the tying run in the game against Rochester and sent it into extra innings. Many extra innings. Twenty-three more. After 32 innings, and playing time of 8:07, the game was suspended, to be resumed on June 23. Left fielder Walker was 1-for-13 in the game, but his double had been key. Ever since, it has been known as “The Longest Game.” The PawSox won it, 3-2, in a mere 18 minutes of play after resumption.

Looking back on the year a decade later, though, 1981 spring training was “the one part of his career where he felt he didn’t get a fair shake.” He told Peter Gammons that he’d just finished a steady climb through the Red Sox system, but Don Zimmer was replaced by Ralph Houk as manager. The Sox signed Jerry Remy to a long-term deal. “I understood that,” he said, “because Remy deserved it. Remy was one person I really respected. What I didn’t understand was that they decided to move Marty Barrett up from Double A and move me out of second base just to make room for him. I’m younger. I’d played Triple A and had a good year. I was working with Eddie Popowski and trying to improve.” There was the matter of a broken finger he suffered that spring. That, he said, set him back, “then one day I picked up the paper and read where I was being moved to the outfield to make room for Barrett.”14

There was, perhaps, another element — race. As Peter Gammons wrote in 1991, “Houk didn’t like Walker. Barrett was [PawSox manager] Joe Morgan’s pet. Curiously, at the time there was a lot of resentment among black players in the organization — including Jim Rice, who privately complained bitterly that a Barrett wouldn’t have been canned for a Chico Walker — and some of the lingering feelings black players have had toward Morgan in the following decade involve the treatment of Walker.”15

Walker’s arm was considered exceptionally good, which is one reason why the PawSox tried him in the outfield for the first time. He had a good year, hitting .277 and showing some power with 17 home runs. He drove in 68, which proved to be a career high.

When called up to Boston, he only got into six September games, but was 6-for-17 (.353). In 1982, though, he never got the call, despite another solid season with Pawtucket — 133 games, 15 homers, 66 RBIs, and a .251 batting average.

Walker spent 1983 and 1984 with the PawSox, too, getting just a brief call-up each year. In four September games for Boston in 1983, he was 2-for-5 (both hits were triples). With Pawtucket, he had 18 homers and batted .269 with 56 RBIs. In 1984, he was brought up for three games in June and drove in a run with a sacrifice fly, but was 0-for-4 officially. In Triple A, he had hit 18 homers again with 51 RBIs on a .263 average.

In October, the Red Sox released him. Three weeks later, he signed as a free agent with the Chicago Cubs.

Walker’s next three years with the Cubs were much the same. Most of the time he was in Des Moines with the Iowa Cubs of the Triple-A American Association. For Iowa, his batting averages were .284, .298, and .244. In each season, however, he put in a stint with the big-league club that was significantly longer than he’d had with Boston.

In 1985, he began the season with Iowa, but was called up in May when Rick Sutcliffe went on the DL and outfielder Gary Matthews looked like he was facing surgery. He appeared in his first of 21 games for Chicago on May 21, though he never once played a full game. He had just one hit — a single –in 12 at-bats. When outfielder Bob Dernier was reactivated after the Fourth of July, Walker was sent back to Des Moines.

In 1986, he was with Iowa for the whole minor-league season. In 138 games, he drove in 65 runs, stole a league-leading 67 bases, and was named team MVP.16 His time in the major leagues was confined to September, but he appeared 28 times and played a complete game in almost every one, either in right field or center. In 112 plate appearances, he hit .277 with an on-base percentage of .339. He also stole 15 bases.

Walker was at the top level twice in 1987. He was on the roster from Opening Day through the last day of May. When the Cubs had signed Andre Dawson in early March, he thought it doomed his chances to play right field. He ended up platooning with Brian Dayett in left. He then came back up again in September. He had played outfield from the season’s start until mid-May, then mostly pinch-hit or pinch-ran for the rest of his time. He hit just .200 in 121 plate appearances, but stole 11 bases.

That October, he asked for a trade and was dealt to the California Angels for minor-league reliever Todd Fischer. Walker hoped that someday he could make his mark on the base paths in the majors. “During a regular 162-game schedule, I feel I’m capable of stealing anywhere from 50 to 100 bases. Given an opportunity, I think I can do those things.”17

At the start of April 1988, he was assigned to play in Canada for the Edmonton Trappers (Pacific Coast League.) “I don’t plan on being with Edmonton the full season,” he said, “I don’t have anything else to prove at this level. But I really don’t have any trouble getting motivated here, because I’ve got some pride and I know what I’ve got to do to get called up.” With a career .234 major-league average at the time, he said, “I admit I haven’t done as well as I should. I haven’t been that successful at the major-league level. But I think a lot of that is opportunity, too.”18

In early May, center fielder Devon White tore cartilage in his right knee and Walker was summoned from the PCL. He played from May 8 to July 1, with action in the outfield and second base to go with some pinch-hitting. He appeared in 33 games and had 86 plate appearances, but got only 12 base hits and two RBIs. On July 5, he was sent back to Edmonton, swapped for Thad Bosley. He did hit .289 for Edmonton over the course of the year. In October, the Angels released him.

In 1989 Walker joined the Toronto Blue Jays organization and spent the year in Triple-A with the Syracuse Chiefs. He hit .239, not that impressive for a 30-year-old player with big-league experience.

In 1990, he was back in the Cubs system, playing in Double A for the Charlotte Knights. He did quite well for them and climbed back to Triple A, again wearing an Iowa Cubs uniform. He led all Cubs minor-leaguers in 1990 with 18 home runs.19 In the 32 games he was with Iowa, he hit .360.

Others might have been discouraged, finding themselves back in the minor leagues, but not Walker. While acknowledging that, “I realize that I’m no star,” he said, “I never thought about quitting…I love the game and I just wanted to get that legitimate shot.”20 As it worked out, the following three seasons (1991 through 1993) were the only three in which he played no minor-league ball and stayed in the majors throughout.

In 1991, Walker got his second stint with the Cubs and had a good, solid year for the fourth-place team. He appeared in 124 games as a utility man; only five teammates played in more. He played 57 games at third base and 53 in the outfield. Jim Essian — for whom Walker had worked in the minors — took over as manager in May. He had Walker bat leadoff and it worked well. He was above .300 much of the season, and into early August. Though he tailed off late and finished at .257, that was still slightly better than the team and league average. He hit .406 as a pinch-hitter.21

Chicago rewarded Walker with a new contract, albeit a one-year deal, boosting him from a reported $110,000 per year to $275,000.22 Jim Lefebvre became the team’s manager. Walker began 1992 with the Cubs but, after 19 games (11 as a pinch-hitter), he was hitting just .115 and was placed on waivers in early May. The Cubs had reportedly been hoping to trade him and were “surprised when the Mets claimed him.”23

Jeff Torborg used Walker frequently and he responded with his best big-league season. In 107 games, he batted a surprising .308 (.369 OBP) — by far the best BA on the team, although he had just 257 trips to the plate. Notable moments included his base hit on May 18 — the only one off the Padres’ Bruce Hurst that night — and a pinch-hit single with the bases loaded in the top of the ninth, which gave the Mets a 6-5 win over the Expos on June 9.24

In 1993, Walker was back with the New York Mets. He appeared in 115 games but was nowhere nearly as productive as in 1992, hitting .225 (.271 OBP), with only 19 RBIs. Despite two new expansion teams in the league, the Mets lost 103 games in 1993. They needed to make some changes. Right after the season, on October 4, Walker was released. His major-league career was complete. He had accomplished something special, though, in his last at-bat. On October 3, playing the Marlins in Miami, Walker came up to bat with two outs in the top of the ninth, facing right-handed reliever Matt Turner, he hit a solo home run to deep right field. It was his 299th big-league base hit. His first hit and his last hit were both home runs.

Looking at some of his splits, he hit substantially better as a right-handed batter (.266) than from the left side (.238), when facing starting pitching. It hadn’t really mattered that much whether he had started the game (.247) or come in as a substitute (.241). He hit about the same on the road as at home.

Walker hung on with Veracruz in the Mexican League. “The summer of ’94. I decided that was it. I thought maybe it’s time for me to do something else.” He’d mainly played winter ball in the offseasons as opposed to other jobs. He was ready for some time off. He had been careful with his finances and hadn’t been forced to seek post-baseball employment. “From savings and all that, I was okay.”

In 1996, his nephew, Antoine Walker, became a first-round pick of the Boston Celtics; the power forward played 12 seasons in the NBA.25 Chico spent some time traveling and hanging out in basketball circles. Over the years, he has supplemented his income with paid appearances at autograph sessions and celebrity golf or other outings, sometimes earning up to $20,000 or $25,000 a year.

In 1999, he got back into baseball for one year as a coach and then manager of the Cook County Cheetahs in the independent Frontier League. The team finished in sixth place, and the conditions were very basic. “It was pretty much traveling just like you were in rookie ball, A ball,” he remembered with a chuckle some 20 years later. “It was a lot of travel.”

Not long before turning 50, in 2007, Walker married. He had met France Neff at one of Antoine Walker’s basketball camps about five years earlier. Her family were Haitian immigrants who had come to the United States when she was about 10 years old and settled in the Boston area.

With his extended family living in the Chicago area and his wife’s in the Boston area, Walker splits his time between the two (he and France did not have children). He has become a devotee of golf, which gets him out and about. “I got into the golf game late, but once I got into it, I love to play all the time. In the summertime, I have family and friends that I play golf with, hang out with, so I’m basically in Chicago. Wintertime, there’s not as much to do and my wife has a good business here. She is the director of a nonprofit organization which serves underprivileged teens with kids. Family Service of Greater Boston.” For nearly 20 years, France A. Neff has been the director of the Family Independence Teen Living Program, promoting self-sufficiency for at-risk urban teenagers with children.26

Walker keeps in touch with the game to some extent. He typically goes to the annual Alumni Day the Red Sox host each year and from time to time will play in a celebrity basketball game for charity. He also does the occasional autograph session or golf outing for the Major League Baseball Alumni Association.

Last revised: August 20, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin. Thanks also to the Boston Red Sox, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and Bill Deane.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Peter Gammons, “It Was A Long Climb for Walker,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1991: 29.

2 Walker played 65 games in the American League (32 for the Red Sox and 33 for the Angels) and 431 games in the National League (239 for the Cubs, in two stints, and 222 for the Mets.)

3 “Mets’ Walker Unhappy with Utility Player Tag,” New York Daily News article reprinted in the Hartford Courant, September 23, 1992: F5A.

4 “Mets’ Walker Unhappy with Utility Player Tag.”

5 Author interview with Chico Walker on May 19, 2020. His birthdate has previously been listed on a number of baseball databases as November 25, 1958, but he states that the correct date is as rendered here.

6 Author interview with Chico Walker on May 1, 2020. All direct quotations which follow and are not otherwise attributed come from this interview.

7 Fred Mitchell, “Matthews May Opt for Surgery,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1985: C3. Years later, Walker reminisced a bit about playing for the Mayor Daley Youth Foundation and other games at Comiskey Park. See Bill Jauss, “Cubs’ Walker Laments Old Comiskey’s Demise,” Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1991: B6.

8 Clearly, he must have stood out for his play in high school to be signed by a big-league team. “I was a pretty good high school player, he granted in the May 2020 interview. “I might have been the only player to get drafted out of Chicago in ’76.”

9 Peter Gammons, “Walker’s Leaving His Mark,” Boston Globe, September 18, 1980: 66.

10 Joe Giuliotti, “Remy Out, Sox Strapped for Infielders,” Boston Herald, July 13, 1980: 7.

11 Paul Katzeff, “All Was Not Lost; Kids Put On A Show for Sox,” Boston Herald, September 8, 1980: 9.

12 Gammons, “It Was A Long Climb for Walker.”

13 Peter Gammons, “Walker Learns to ‘Never Slow Down’,” Boston Globe, September 21, 1980: 78.

14 Peter Gammons, “It Was A Long Climb for Walker,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1991: 29.

15 Gammons, “It Was A Long Climb for Walker.”

16 Fred Mitchell, “Exam Time for Cub Hopefuls,” Chicago Tribune, September 5, 1986: C4.

17 Fred Mitchell, “Cubs Talked A Good Game,” Chicago Tribune, February 14, 1988: 2.

18 Mike Burrows, “Walker Waits for His Next Shot at Majors,” Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph, May 6, 1988: C5.

19 Joe Goddard, “Walker Pulls Infield Switch,” Chicago Sun-Times, March 5, 1991: 90.

20 Peter Gammons, “It Was A Long Climb for Walker,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1991: 29.

21 Paul Sullivan, “Lefebvre: NL Puts More Emphasis on Bench,” Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1992: C9

22 Alan Solomon, “Cubs, Walker Get Together on 1-Year Contract,” Chicago Tribune, December 24, 1991: B11.

23 “NL Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1992: C5.

24 When Curt Schilling pitched a one-hitter against the Mets on September 9, the one hit was a Bobby Bonilla home run. Walker was the only other Met to reach first base, but he did so on a catcher’s interference call.

25 https://www.basketball-reference.com/players/w/walkean02.html

26 The social service organization traces its roots back to 1835. See the website at http://fsgb.org/about-us.html

Full Name

Cleotha Walker

Born

November 25, 1958 at Jackson, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.