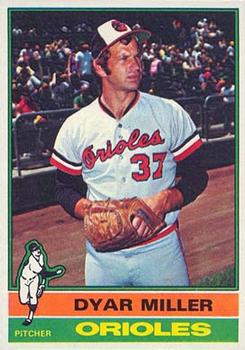

Dyar Miller

Personifying perseverance, Dyar Miller spent more than 50 years in professional baseball despite being released three weeks after signing his first contract. A right-hander with an effective fastball-slider combination, he pitched for the Orioles, Angels, Blue Jays, and Mets after debuting at age 29. Over parts of seven seasons (1975 to 1981), Miller was 23-17 with 22 saves and a 3.23 ERA in 251 games.

Personifying perseverance, Dyar Miller spent more than 50 years in professional baseball despite being released three weeks after signing his first contract. A right-hander with an effective fastball-slider combination, he pitched for the Orioles, Angels, Blue Jays, and Mets after debuting at age 29. Over parts of seven seasons (1975 to 1981), Miller was 23-17 with 22 saves and a 3.23 ERA in 251 games.

Dyar K. Miller was born on May 29, 1946, in Batesville, Indiana, about 50 miles west of Cincinnati in Decatur County. He was the fifth of Carl H. and Goldia (Williams) Miller’s eight children – five boys and three girls – but the first to be delivered in a hospital. The farm on which they lived in Saltcreek Township had been in the family since their ancestors’ arrival from Germany more than a century earlier.

The Millers moved to Keshkonong, Missouri, when Dyar was seven. Though they stayed in the tiny town just north of the Arkansas border for only two years, it was there that he was introduced to his future occupation. When his mother tuned in to Harry Caray’s broadcast of a Cardinals-Cubs game on KALM radio, Dyar asked what she was listening to. “Professional baseball,” she replied, prompting him to inquire what “professional” meant. After she explained that the players were paid to play, he said, “That’s what I’m going to do.”1 He listened to every Cardinals game from that day forward.

“My siblings liked to play catch and hit high flies and grounders for fun after a hard day’s work on the farm,” Miller described.2 Although there was no town Little League program when he returned to Indiana after third grade, he recalled. “We’d get up at 6 a.m., do the chores, milk the cows, then go to school. After school, more chores…I’d bale hay so much my arms ached. Never had to do much weight training.”3 Around age 14, he played for a Napoleon-based Babe Ruth League club. At New Point High School, the baseball team played only a seven-game fall season, but Miller, a catcher-pitcher, once struck out 20 batters in a single contest. He also ran track, but made his biggest impact on the basketball court, averaging more than 20 points per game over three years for a Little Giants team coached by former Utah State University star “Max the Magician” Perry.4 After Miller graduated seventh in his class of 14 seniors in 1964, he accepted a basketball scholarship to attend Utah State. The Aggies had made three straight NCAA tournament appearances when the field was still limited to 25 teams.

Following a summer of American Legion baseball, Miller commenced his pursuit of a history degree and suited up for USU’s freshman hoops squad. He topped the team with 19 points and 10 rebounds in a victory on March 1, 1965.5 The Student Life newspaper described the 6-foot-1, 195-pound Miller as a “rugged forward” and a “possible varsity prospect” for his sophomore year, but Utah State declined to renew his basketball scholarship.6 Instead, he was offered partial assistance based on the promise he’d demonstrated for the baseball team that spring. Miller was primarily a catcher during his Aggies career, though he once pitched the opener of a doubleheader before shifting to behind the plate.7 During summers back home, he caught for the Batesville Bullets in the Tri-County League, a circuit he characterized as “kind of a beer league among Indiana villages.” His arm impressed Phillies’ birddog Ed French, who summoned famed Philadelphia scout Tony Lucadello. On July 7, 1968, Miller’s father drove him to Dayton to sign a professional contract for $1,500.8

Miller debuted with the Huron (South Dakota) Phillies in the Single-A Northern League in 1968. First-time manager Dallas Green’s roster included future All-Stars, Greg Luzinski and Manny Trillo, and pitcher Larry Cox, who’d later reach the majors as a catcher. Miller would make the opposite transition, though not with the Phillies. After four games in which he went 1-for-7, he was released a mere three weeks after signing. “I always thought I was a pretty good catcher but hitting, well, that’s another matter,” he confessed. It’s possible that Miller’s draft status factored into his quick release. American troop levels in the Vietnam War peaked in 1968 and Miller’s 1-A classification as a four-year college graduate meant that he was available for service. He’d tried joining the Air Force Reserve a couple years earlier, but his waitlist number was around 750. As it happened, he was accepted into the Reserve shortly after his draft board appointment, probably saving him from a three- to four-year stint in Vietnam.

After being cut, Miller began substitute teaching at North Decatur High School. “I still wanted to stay in baseball, but I didn’t know what to do. Then I remembered that a cousin of mine was married to an Oriole scout,” he explained.9 That scout, Jim Frey, had visited the Miller farm a few times during Dyar’s childhood. “There was a knock at the door and there he was,” Frey recalled. “I asked him about his background and when he told me he had caught for Huron, I went down to the cellar to see if I had a report on him.”10 Indeed, Frey had seen Miller play in Aberdeen, South Dakota, and noted his “strong arm.” After Miller confirmed that he’d pitched before, Frey arranged an invitation to Orioles’ spring training in 1969.

In minor-league camp, Miller was issued wool uniform number 143 and earned the last spot on the pitching staff of the Stockton Ports, Baltimore’s Single-A California League affiliate. Through June 1, manager Bill Werle used him sparingly. On June 2, however, when the big-league Orioles visited for an exhibition, Miller earned Stockton’s one-run victory by limiting the majors’ best team to a single tally over the final four frames. “We’ve got to get that guy some innings,” Baltimore skipper Earl Weaver told Werle. “Put him in the rotation.”11 Miller became a starter, hurled a 13-inning complete game at one point and finished the season 4-4 with a 2.33 ERA in 25 appearances (10 starts). In 116 innings, he struck out 111 and allowed only 80 hits. Stockton won the California League championship.

Miller advanced to the Double-A Texas League in 1970 and established himself as the ace of the Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs. On May 9, he hurled a seven-inning no-hitter against the Amarillo Giants in the first game of a twin bill and knocked in three runs with a single and his only professional homer.12 Fifteen days later, he held the El Paso Sun Kings hitless into the ninth inning before finishing with a two-hitter.13 Nevertheless, his record was only 5-6 after a June 16 loss to the Arkansas Travelers in which he retired the first 19 batters.14 In defeating the same team on July 17, he set down the final 17 in a row.15 Miller was the winning pitcher in the Texas League All Star Game on August 18 in Albuquerque.16 In regulation action for a Spurs club that finished 10 games under .500, he completed 10 of his 25 starts and went 12-10 with a 3.23 ERA, surrendering only five homers in 170 innings.

In the pitching-rich Baltimore organization, however, Miller remained in Double-A. Over the next two seasons, he made 24 of his 40 appearances out of the bullpen, averaging 5.6 walks per nine innings. His workload decreased substantially: to 88 innings back at Dallas-Fort Worth in 1971, and only 49 frames with the Orioles’ new Southern League affiliate in Asheville, North Carolina, the following year. Mid-season Air Force Reserve commitments made it difficult to maintain consistency. “It’s tough for a pitcher to be gone on military duty because once he gets in a groove, he has to work to stay in it,” Miller observed. “For a hitter, a weekend off sometimes helps.”17 At 26, Miller was Asheville’s oldest player in 1972, Roommate Doug DeCinces told him, “You ought to think about being a coach.”18

That winter, Miller accepted an invitation from White Sox scout Deacon Jones to earn extra money pitching in Mexico. He drove from Indiana to join the Mayos de Navojoa and experienced what he described as the “turning point of my career.” Jones – a former first baseman – told him, “Try this grip. Some of the Chicago pitchers are using it.” Thus, Miller discovered an effective slider.19 He struck out 19 batters to break Vicente Romo’s 1967 Mexican Pacific League record in a 1-0, one-hit victory over the Algodoneros de Guasave.20 In the circuit’s finals, he pitched a two-hit gem against the Yaquis de Obregón but lost an elimination game, 1-0.21

In 1973, Miller advanced to the Triple-A International League and pitched well for the Rochester Red Wings (6-3, 2.75). He was limited to 72 innings over 15 appearances (13 starts), however, plagued by a back injury initially suffered when he slipped while running in the sandy outfield at Biscayne College during spring training. “The pain got so bad in the lower right side of my back I couldn’t reach the resin bag,” he explained after leaving a July 28 contest early despite increasing his consecutive scoreless innings streak to 17.22 His back bothered him all year, but he finally found relief after the season concluded. “I wanted to pitch winter ball and I knew I had to fix my back. So, I went to Cincinnati to see one of the Reds’ specialists, an orthopedic man. He diagnosed it as an inflammation in the lower sacroiliac. Two cortisone shots and it was gone.”23 Miller hurled 125 innings in the Mexican Pacific League.24

Miller was a non-roster invitee to Orioles spring training in 1974 but worked only one Grapefruit League inning. “I was happy to get the experience and meet the players,” he said. “At the same time, I was sad about the whole thing. I never had a chance to make the club.”25 Orioles manager Earl Weaver told him, “We liked your attitude” and encouraged him to put together a good year at Rochester, promising, “Whoever is throwing the best, we call up” should the major league team need pitching.

Miller was 3-0 with a 2.84 ERA when Baltimore temporarily lost Don Hood because of a death in his family on Memorial Day weekend, yet the Orioles called up Wayne Garland instead. “I was really ticked off when it happened,” Miller acknowledged. “I’ve had something like this happen to me for about the 5,000th time in my career and I’m really getting tired of it. After a while you say, ‘Is it really worth it or what?’”26

By midsummer, Miller’s record was 11-2.27 He made the IL All-Star team.28 “Being healthy has made the difference,” he insisted. “I’ll bet my fastball has a good half-foot tail on it, maybe more.”29 Ray Miller (no relation), Baltimore’s minor league pitching instructor, remarked, “Dyar has gone from NP [no prospect] two years ago to a real good prospect now.”30 Miller finished the regular season 12-8 with a 2.70 ERA in a career-high 190 innings. His 138 strikeouts, also a personal best, were the most by an IL right-hander. In the playoffs, Miller won three of four decisions to help Rochester claim the championship.31 He followed an 11-strikeout victory over the Memphis Chicks in the semifinal clincher with a 10-strikeout triumph over the Syracuse Chiefs in the championship series.32 “Dyar Miller is a super competitor,” raved Syracuse and future Hall of Fame skipper Bobby Cox. “There’s a lot to his physical makeup and he throws as hard as anybody on Rochester’s staff.”33

Next, Miller pitched in the Puerto Rican Winter League, mostly in relief. His manager with the Santurce Crabbers, Frank Robinson, had recently become the majors’ first-ever African American skipper when the Cleveland Indians hired him. Shortly before Christmas, Miller received an early present when Robinson handed him a letter from the Orioles informing the pitcher that he’d been added to Baltimore’s 40-man roster.

In spring training 1975, Miller went 2-0 with a club-best 1.80 ERA but was sent back to Rochester for a third straight year. “At first, he was fine,” reported Weaver, who delivered the news. “Then he went out to do the rest of his work and you could see the frustration building up. The more he ran, the redder he got…It brought tears to my eyes. It really did.”34 Miller acknowledged his anguish. “I guess you could say I was heartbroken,” he said. “I thought my major league career was gone and I was certain I’d never pitch for the Orioles.”35

Baltimore scout Jim Russo tried to convince the Texas Rangers to find a spot for Miller.36 GM Frank Cashen gave him permission to contact teams to gauge their interest. “I had this wild notion to pack up and go home if I wasn’t traded by June 15,” Miller confessed.37

Miller was asked to work out of the bullpen at Rochester. “I didn’t like it at first because I figured my only chance was to win a lot of games right away and hope some other team would trade for me,” he said.38 In 19 appearances (one start), he thrived, going 5-0 with a 2.20 ERA and seven saves, striking out 38 and allowing only 24 hits in 41 innings. Meanwhile the Orioles, at 16-26, had the worst record in the American League. Neither Garland nor Doyle Alexander – both of whom preferred to start – were succeeding as right-handed relievers. When Baltimore dealt struggling Bob Reynolds to Detroit on May 29, Miller was called up to the majors. It was his 29th birthday.

On June 9, 1975, Miller made his big league debut, in the 14th inning against the three-time defending World Series champion Oakland A’s in Baltimore. He struck out the first batter he faced, Hall of Famer Billy Williams, and worked 1 ⅓ innings but was charged with the Orioles’ 4-3 defeat after surrendering an RBI single to Joe Rudi in the 15th. Two nights later, Miller notched his first win in a 10-inning affair in Texas. When the Orioles went 21-6 immediately after the All-Star break to move into second place. Miller appeared in nine games –all Baltimore victories– and earned two wins and six saves. On August 6, he was credited with his fifth save when he finished off a Baltimore win in Detroit with 3 ⅔ innings of one-hit, shutout work, striking out a career-high six. “I like relief pitching now,” he insisted. “I think it helps me concentrate more. I found my mind wandering as a starter. Usually, an organization trains guys from the beginning for a certain job, but that’s [not] the way my career has run. Mine is not an ordinary career.”39

“Pitching out of the bullpen is a lot different,” Miller noted. “I throw mostly fastballs and sliders when I relieve and not too many curves or changeups.”40 Baltimore pitching coach George Bamberger encouraged him to tuck his left shoulder in tighter during his delivery and stop swinging his hands over his head on his windup. “My control is the best it’s ever been and I’m keeping the ball down,” Miller said. “You have to throw strikes when you come in from the bullpen and George has helped me to do that.”41 Miller completed his rookie campaign 6-3 with a 2.72 ERA and a team-leading eight saves in 30 appearances. The Orioles went 74-43 after he joined the team.

On Opening Day 1976, Miller saved Jim Palmer’s 1-0 victory over the Red Sox and Ferguson Jenkins in Baltimore, retiring Hall of Famers Jim Rice, Carl Yastrzemski, and Carlton Fisk in a perfect ninth inning. Miller went on to post a 2.94 ERA and top the team with 49 relief appearances as the Orioles finished second again. His seven saves were the most by a Baltimore righty, one behind Tippy Martinez for the club lead. In two outstanding long relief outings, he tossed 7 ⅔ innings of one-hit shutout ball against the Red Sox on June 22, and he worked eight innings to earn a victory against the White Sox on August 14.

Miller notched a save and a win in his first two outings of 1977, but he appeared in only six of 36 games between April 30 and June 6, allowing eight walks and four home runs in 8 ⅔ innings. Baltimore GM Hank Peters conceded that a lack of work may have contributed to Miller’s ineffectiveness but attributed the inactivity to Weaver’s loss of confidence in the pitcher. After Miller pitched well in back-to-back outings, he was dealt to the California Angels for righty reliever Dick Drago on June 13. “We were looking for an experienced pitcher who could work out of the bullpen and throw strikes,” Peters explained, “Dyar did a good job for us for a couple of years.”42

By season’s end, Miller had established personal major-league bests in both appearances (53) and innings (114 ⅔). With the Angels, he went 4-4 with 4 saves and a 3.02 ERA in 41 outings and led the club in relief innings. On July 14, he faced only seven batters to record nine outs after inducing a triple-play grounder with his first pitch to Seattle’s Leroy Stanton.43 California had fired manager Norm Sherry a few days earlier and finished fifth under replacement Dave Garcia.

In 1978, the Angels axed Garcia at the end of May and hired Jim Fregosi, who liked Miller and used him in 17 of his first 51 games as skipper. Miller pitched to a 1.67 ERA in 37 ⅔ innings before bruising his pitching shoulder in a home-plate collision with Jason Thompson after a game-ending passed ball on July 23 in Detroit.44 He spent nearly a month on the disabled list. Although he wound up 6-2 with a 2.66 ERA in 41 appearances for a California club that finished second for the first time in franchise history, he was not as effective after returning.

Miller went 1-0 with a 3.31 ERA in his first 14 outings of 1979, but American League hitters batted .319 against him. On June 6, the first-place Angels sold the 33-year-old reliever to the team with the majors’ worst record, the Toronto Blue Jays. In 10 appearances for Toronto, Miller was clobbered for a 10.57 ERA. “I was really trying to work on another pitch, a palm ball with [pitching coach] Bob Miller [no relation],” he explained. On July 30, when the Blue Jays purchased first baseman Tony Solaita from the Expos, Miller was sent to Montreal’s Denver Bears farm club as part of the deal.45 His ERA in the Triple-A American Association was 1.80 in 15 games, but Montreal was unable to bring him back to the majors because the New York Mets put in a waiver claim.46

After the Expos released Miller in spring training 1980, he called Frank Cashen – who’d just become Mets GM – and wound up in that organization after all. He began an extended spring training until a spot opened with one of New York’s already-stocked minor league affiliates. Miller wound up in the International League with the Tidewater Tides, where he was 4-2 with four saves and a 4.67 ERA in 29 games. The Mets had a .500 record on July 18 when they brought him back to the majors. Despite Miller’s outstanding 1.93 ERA in 31 outings, New York went into freefall and finished 67-95.

In 1981, Miller spent the entire strike-shortened season with the Mets, posting a 1-0 record and 3.29 ERA in what proved to be his final 23 big league appearances. New York released him that October. Miller hoped to catch on with the Reds’ Triple-A Indianapolis team near the farm he’d purchased in Greensburg, Indiana, in 1982. When Cincinnati’s brass dragged their feet, he called Cardinals’ executive Joe McDonald and landed with a different American Association club, the Louisville Redbirds. He recorded a 2.91 ERA in 46 outings and led the team with a career-high 10 saves. Louisville had a new manager in 1983, Jim Fregosi, and St. Louis farm director Lee Thomas asked Miller to help his old friend, though he couldn’t promise that he’d be activated right away. Miller, the oldest player in the circuit that season at 37, went 5-3 with six saves and a 3.56 ERA in 32 games as the Redbirds finished with the league’s best regular-season record.

Since the 1981 strike, Miller had been experiencing stomach pains, and he was diagnosed with colon cancer on December 8, 1983. Two days later, he had two feet of colon removed in major surgery. “It was no worse than facing George Brett or Reggie Jackson,” he insisted. “You’ve either got it or you don’t. There’s nothing much you can do about it in that situation.”47 He returned to the mound with Louisville in 1984. After a half-dozen appearances, the team approached him in July and said, “Here’s a dollar. We want to tear up your old contract and give you a new one.” Miller spent the rest of the season as the pitching and first-base coach for a championship Redbirds club. Beginning in 1985, he worked exclusively with the hurlers as perhaps the first full-time pitching coach in Double-A history.

In 1986, Fregosi left Louisville in mid-season to become manager of the Chicago White Sox. Miller joined him as the bullpen coach in 1987 and became the club’s pitching instructor a year later. After Fregosi was fired following a fifth-place finish, Miller wound up in the Detroit Tigers organization as a roving pitching instructor in 1989. He finished the year managing the Orlando Juice of the Senior Professional Baseball Association.

Miller was the pitching coach for the [Double-A] Eastern League champion London Tigers in 1990, before moving on to similar roles in the Cleveland Indians system for four seasons. In both 1992 and 1993, he helped two Triple-A title teams win titles: the Colorado Springs Sky Sox of the Pacific Coast League and Charlotte Knights of the American Association, respectively. In 1995, he won another championship in the first of his two years back in Louisville.

Miller was inducted into the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007, the same year that he finished a seven-year run as the pitching coach for the Cardinals’ Triple-A Memphis Redbirds. After four more seasons working with St. Louis’s minor leaguers, he joined the major league staff as bullpen coach in 2012. He spent 2013 to 2018 in the Houston Astros’ organization. After some of the Astros’ brass moved on to Baltimore, Miller was a guest instructor at Orioles’ spring training through 2020. “I knew about one-tenth or less when I was pitching than I do now,” he remarked in 2019.48

“In retrospect, I was pretty raw, and I probably should’ve learned another pitch,” he said. Nevertheless, despite being released only four games into his career, the former college basketball recruit lasted more than a half-century in professional baseball and earned three World Series rings with the Cardinals (2006 and 2011) and Astros (2017). In 2021, Miller turned 75 in his first season entirely out of uniform since 1967. He and his second wife, Bertha, live in Indianapolis. Their family includes six children and 17 grandchildren between them.

Last revised: June 9, 2021

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dyar Miller (telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, April 14, 2021).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Unless otherwise cited, all Dyar Miller quotes are from a telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, April 14, 2021 (hereafter Miller-Allen interview).

2 Pat Smith, “Where Are They Now: Dyar Miller,” Daily News (Greensburg, Indiana), April 27, 2015, https://www.greensburgdailynews.com/news/local_news/where-are-they-now-dyar-miller/article_033de4c0-339e-50ea-8741-701170a016de.html (last accessed April 27, 2021).

3 Jim Castor, “Physical Pain’s Gone for Miller,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), April 2, 1974: 27.

4 Dyar Miller, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, March 4, 1969.

5 Lynn Roderick, “Ramblers Top Rangely, 87-71,” Student Life (Logan, Utah), March 3, 1965: 4.

6 “Ramblers Finish with 5-8 Mark,” Student Life, March 12, 1965: 6.

7 Miller, Publicity Questionnaire.

8 Miller-Allen Interview.

9 Ken Nigro, “Bird Call for Aid Finds Miller Happy, Ready,” Baltimore Sun, May 31, 1975: B3.

10 Nigro, “Bird Call for Aid Finds Miller Happy, Ready.”

11 Miller-Allen Interview.

12 “Spurs’ Miller Baffles Amarillo on No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1970: 45.

13 “Miller Almost Pitches Another No-Hit Gem,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1970: 39.

14 “Miller Retires 19 in Row,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1970: 42.

15 “Retires 17 Straight,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1970: 44.

16 Carlos Salazar, “Rivers’ Bat and West’s Speed Decide Texas Star Game,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1970: 37.

17 “International League,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1973: 32.

18 Miller-Allen Interview.

19 Miller-Allen Interview.

20 Tomás Morales, “Miller Whiffs 19 in Mexico,” The Sporting News, January 20, 1973: 45.

21 Tomás Morales, “Obregón Mexican Champions,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1973: 47.

22 “Miller Strings in Pain,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1973: 38.

23 Castor, “Physical Pain’s Gone for Miller.”

24 Ray Buck, “Red Wings’ Miller Dying for Longer Look,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 39.

25 Buck, “Red Wings’ Miller Dying for Longer Look.”

26 Buck, “Red Wings’ Miller Dying for Longer Look.”

27 1975 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 73.

28 “Andrews Top Selection for IL All-Star Team,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1974: 35.

29 “Int. Items,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1974: 34.

30 Buck, “Red Wings’ Miller Dying for Longer Look.”

31 1975 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 73.

32 “Miller Whiffs Increase,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1974: 36.

33 Larry Bump, “Mitchell’s Sure He’ll Even Series,” Democrat and Chronicle, September 19,1974: 44.

34 Jim Henneman, “Ex-Reject Miller Thriving on Oriole Relief,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1975: 9.

35 Nigro, “Bird Call for Aid Finds Miller Happy, Ready,”

36 Henneman, “Ex-Reject Miller Thriving on Oriole Relief.”

37 Nigro, “Bird Call for Aid Finds Miller Happy, Ready.”

38 Henneman, “Ex-Reject Miller Thriving on Oriole Relief.”

39 Ken Nigro, “Desire Paid Off for Dyar Miller,” Baltimore Sun, August 23, 1975: B3.

40 Nigro, “Bird Call for Aid Finds Miller Happy, Ready.”

41 Nigro, “Desire Paid Off for Dyar Miller.”

42 Jim Henneman, “Orioles Toss Burning Problem to Fireman Drago,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977: 18.

43 Dick Miller, “Angel Notebook,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1977: 17.

44 “Angel Notes,” Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1978: H1.

45 Neil MaCarl, “Blue Jays Notes,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1979: 13.

46 Miller-Allen Interview.

47 Kim Rogers, “Miller Just Glad to Be on Mound,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1984: 30.

48 Steve Krah, “Batesville Native Miller Sees Pitching Change in Half Century of Pro Baseball,” July 17,2019, https://takeoutyourscorecards.wordpress.com/2019/07/17/batesville-native-miller-sees-pitching-change-in-half-century-of-pro-baseball/ (last accessed April 28,2021).

Full Name

Dyar K. Miller

Born

May 29, 1946 at Batesville, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.