Harry Stovey

There exists a long list of forgotten nineteenth-century baseball stars who played during the game’s formative stages and under relative anonymity besides being a name in a newspaper. While the game was fundamentally the same, it was evolving in an era that saw many rule changes and ballparks with vastly varying dimensions. There were no bright lights or television, and record-keeping was inconsistent. One of the greatest players of the nineteenth century was Harry Stovey.

There exists a long list of forgotten nineteenth-century baseball stars who played during the game’s formative stages and under relative anonymity besides being a name in a newspaper. While the game was fundamentally the same, it was evolving in an era that saw many rule changes and ballparks with vastly varying dimensions. There were no bright lights or television, and record-keeping was inconsistent. One of the greatest players of the nineteenth century was Harry Stovey.

Stovey was “one of baseball’s first dual threats” in the judgment of Matt Kelly at the Baseball Hall of Fame.1 He possessed a rare combination of power and speed that set him apart from other nineteenth-century players. He was also an innovator on the basepaths, introducing sliding techniques to the game that had never before been seen. Yet, despite the enshrinement of many of his contemporaries in the Baseball Hall of Fame, Stovey remains a forgotten star who, more than 120 years after his playing career ended, continues to be overlooked by those guarding the gates of Cooperstown.

Harold Duffield Stow was born on December 20, 1856, in Philadelphia.2 He was the eighth of nine children born to John and Rachel (Duffield) Stow (or Stowe by other accounts).3 The Philadelphia almanac that year lists John’s profession as a watchman. Census and other records identify him as a shoemaker. The Stows and Duffields traced their origins to England and both sides of the family had long histories in the United States dating back to at least the early eighteenth century. The Stows had notable Philadelphians in their family tree.

Harry Stow was a direct descendant of an earlier John Stow, a Philadelphia founder who along with his partner John Pass, is credited with recasting the Liberty Bell after it cracked. At Stow’s foundry on Second Street, the bell was broken into small pieces, melted down, and cast into a new bell. The two founders found that the metal was too brittle, and augmented it by about 10 percent, using copper. The bell was ready in March 1753, and Norris reported that the lettering (which included the founders’ names and the year) was even clearer on the new bell than on the old.4 The Stow surname, along with the surname Pass, appears on the upper rim of bell. This is significant as it is one of a few pieces of evidence that point to the proper spelling of the family’s surname.5

While relatively little is known about Harry’s early childhood and education, his early life was certainly shaped by the events surrounding the Civil War. Philadelphia during the Civil War was an important source of troops, money, weapons, medical care, and supplies for the Union.

The Stow family resided in the eastern section of the Kensington District, a working-class community known for its large Irish Catholic and English-American communities.

The Stows, like many of the area families, contributed to the war effort. Harry’s older sisters worked in Kensington’s wool mills and his older brother John joined the 90th Regiment of Pennsylvania Infantry, a unit made up entirely of volunteers from Philadelphia.6 It was also during this time that Harry lost his older brother Edwin. On June 14, 1862, Edwin unexpectedly died of an intussusception, a bowel obstruction, at the age of 13.

Harry loved baseball from an early age and as a youngster he spent what his parents considered an abnormal amount of time playing the game, and the more he played, the better he got.7 In fact, his mother abhorred the game and strongly disapproved of Harry playing. Her hope was that Harry would dedicate his time to learning a trade. When he was not on the sandlots the adolescent Stovey, like many of his contemporaries, learned a trade. He apprenticed and was trained as a cooper.8

Stovey began his ballplaying career as a pitcher with the Defiance Club of Philadelphia in 1877 in the League Alliance. In an effort to conceal his ballplaying from his mother, Harry played under the name of Stovey to avoid the name Stow being used in accounts of local baseball games.9 After enjoying success with Defiance, Stovey joined the Philadelphia Athletics club, which had been expelled from the National League at the end of the 1876 season and also was in the League Alliance.

He spent the next two seasons playing minor-league ball for the New Bedford Clam-Eaters under their nomadic manager, Frank Bancroft. Stovey took a liking to New Bedford and a young woman named Mary Walker. Stovey and Mary were married in July of 1879 and New Bedford would become Stovey’s adopted home.10

In 1880 Bancroft was hired as manager of the National League’s Worcester Ruby Legs and took Stovey along with him. Stovey made his major-league debut on May 1, 1880. Two-and-a-half months later, on July 17, he hit his first major-league home run when he connected off the Cleveland Blues’ Jim McCormick, who led the National League with 45 victories that year. On September 21 Stovey collected four hits, including two home runs, off right-hander Mickey Welch as the Ruby Legs routed the Troy Trojans, 17-2. Four of Stovey’s six home runs that year came at the expense of Welch.

Splitting time between first base and the outfield, the 23-year-old right-handed-hitting Stovey enjoyed a productive rookie campaign. While his .265 batting average may not have been that awe-inspiring, Stovey did lead the league with 14 triples and tied Boston’s Jim O’Rourke for the lead in home runs with six. He also added 21 doubles, sixth most in the league, and finished second in the league in runs scored (76) and total bases (161).

Early in 1880 Stovey and his wife welcomed their first daughter, Elizzia, who would go by Lizzie. During the offseason, Stovey supported his young family by working as the night clerk at the Bancroft House in New Bedford.11 The Ruby Legs manager, who had interests in the local theater and entertainment industry, had opened the Bancroft House to meet the needs of “managers, agents, and [theater] companies visiting New Bedford.”12 Bancroft would apply the same skills and abilities that made him successful in the theater industry – specifically his ability to recognize new trends – to the growing popularity of baseball.

The Ruby Legs finished in fifth place during their first season. However, the team was struggling financially. The club’s board of directors concluded that a professional manager like Bancroft was not worth the investment.13 Bancroft found employment as manager of the National League’s newest team, the Detroit Wolverines, in 1881. The move signaled the start of precipitous decline for the Ruby Legs’ fortunes in Worcester.

With Bancroft no longer at the helm, a rift occurred between player-manager Mike Dorgan and star pitcher Lee Richmond, who a year earlier had authored major-league baseball’s first perfect game. The conflict caused Richmond to quit the team. On August 17 with the team in seventh place with a 24-32 record, the Ruby Legs suspended Dorgan (who immediately signed with Bancroft’s Wolverines) and named Stovey manager for the remainder of the season. The Ruby Legs were 8-18 under Stovey and finished the season in last place, 23 games behind the pennant-winning Chicago White Stockings.

Stovey’s power numbers dipped slightly in 1881. He finished the year with a .270 batting average, 25 doubles, 7 triples, and 2 home runs. His OPS dropped from .742 the previous year to .696. It was the last year his OPS would dip below .750 until 1892. Defensively he appeared in more games at first base than he did in the outfield.

Throughout his career it was often said that Stovey had sure hands and a strong, accurate arm with great range. Statistically, he was an above-average first baseman. He finished in the top four in the league in range factor from 1881 to 1885 and in the top five in fielding percentage during the same years. As of 2019, his 165 career outfield assists place him in the top 100 all-time.

The 1882 season was the final one for Stovey and the Ruby Legs in Worcester. The team continued its free fall in the National League standings and finished in last place with an 18-66 record. Things got so bad that the team’s regular-season finale at the Agricultural County Fair Grounds on September 29 drew a crowd of just 25 patrons, an improvement over the day before, when they drew just six.14

Despite playing for poor teams – the Ruby Legs had a meager .361 winning percentage during their three NL seasons – Stovey continued to develop into one of the game’s most exciting young players. He improved his batting average to .289 and scored 90 runs as his reputation as a daring baserunner grew. He also hit five home runs, which tied him for fourth best in the circuit.

After Worcester disbanded, Stovey was lured back to Philadelphia by Athletics owners Lew Simmons, Billy Sharsig, and Charlie Mason, who reportedly offered him a salary of $2,000, a 60 percent raise over what he was earning with the Ruby Legs.15 His signing was a coup for the American Association. Philadelphia was one of the cities in which the Association was in direct competition with the National League and the articulate, well-mannered, handsome, and home-grown 5-foot-11, 175-pound Stovey gave them a decided advantage in winning the hearts and loyalties of Philadelphia baseball fans over the cellar-dwelling Quakers of the National League.

Stovey and fellow National League imports Lon Knight and pitcher Bobby Matthews joined an Athletics team that went 41-34 and finished in second place in the American Association’s inaugural season. The 26-year-old Stovey quickly established himself as the game’s premier baserunner and power hitter, proving to be the offensive sparkplug the team needed to win the Association championship. Stovey led the league in runs scored, doubles, home runs, total bases, and slugging percentage. He was also considered the best baserunner in the game.16

In fact, Stovey was an innovator on the basepaths. He is credited with inventing sliding pads to protect the often bruised and scraped hips he suffered while sliding on the crudely manicured nineteenth-century fields. He is recognized as one of the first baserunners to slide feet-first into bases and mastering the technique of the pop-up slide, a revolutionary method of going into a base that put added pressure on the defense.17 However, Stovey’s aggressive sliding led to many leg injuries during his career.

Despite his aggressiveness on the basepaths, Stovey was often referred to as “Gentleman Harry” for his clean play. Alfred Henry Spink, author of The National Game, wrote of Stovey in 1910: “He always slid feet first but was not ‘nasty’ with his feet in the way of trying to hurt the baseman, as some of his imitators were.”18

According to Edward Achorn in The Summer of Beer and Whiskey, on the 1883 American Association season, Stovey and many of the Athletics were banged up as they limped toward the finish line for the Association pennant. Stovey was suffering from a sprained ankle that “had turned him into a sad parody of himself on the base paths.”19 Achorn chronicled the last half-inning of the Athletics’ pennant-clinching victory on September 28 in which Stovey fittingly scored the pennant-winning run. The Athletics and the Louisville Eclipse were tied, 6-6, and right-hander Guy Hecker was on the mound as the Athletics came to bat in the bottom of the 10th inning.

Now Harry Stovey pulled a bat from the box at the end of the bench and limped to home plate. … Hecker, either wary of Stovey or incapable of controlling his pitches at this point, kept the ball away from the plate, finally walking the batter. When an exhausted Hecker followed with a wild pitch, Stovey hobbled down to second base – not quite scoring position, this time, given the runner’s lame ankle.

Captain Lon Knight stepped to the plate. Throughout the pennant stretch he had repeatedly made clutch plays that kept the Athletics alive. Now he ripped a single to left field.

Stovey barely made it to third.

It was up to Mike Moynahan. He had enjoyed a fine day, going 2-for-4 at the plate and making nine assists at shortstop, with only one error. Hecker held the ball, stared at the plate, took a run and fired. Moynahan swung and connected. At the crack of the bat, left fielder Pete Browning and center fielder Leech Maskrey dashed for the ball as it shot between them. Harry Stovey who led the American Association with 109 runs scored stumbled home, wincing, with number 110.20

When the team returned to Philadelphia, a great victory celebration was held. At a banquet each Athletic player was presented with a gold badge bearing his name and the inscription “Athletic Base Ball Champions of 1884” (denoting their reign until the end of the next season).21 Mason, one of the Athletics owners, also presented Stovey, whose “extraordinary grace and drive had sustained the club during its crucial final six weeks,” with a gold watch and chain to commemorate his leadership.22

Stovey, who became the first major leaguer to hit 10 home runs in a season, set the single-season home-run record with 14 during the Athletics’ championship run, out-homering five of the other seven Association teams.23 However, his record lasted only one year. In 1884 Ned Williamson and three of his Chicago White Stockings teammates (Fred Pfeffer, Abner Dalrymple, and Cap Anson) surpassed Stovey. Williamson nearly doubled Stovey’s mark with 27.24

There was more to Stovey’s year than setting home-run records and contributing to a championship season with his hometown Athletics. In 1883 he and Mary welcome their second daughter, Susan. Two years later a third daughter, Harriett, was born.

Building on his success of the previous year, Stovey enjoyed an even better season at the plate in 1884. One highlight of the season came on August 18 when Stovey had three triples and two singles in the Athletics’ 20-1 thrashing of the Baltimore Orioles. Two of his triples came in the eighth inning. He was the third major leaguer to hit two triples in an inning.25

In 104 games played that season (all at first base), Stovey hit .326 with 22 doubles, a league-leading 23 triples, 10 home runs (second to Cincinnati’s John Reilly who clouted 11), and 83 RBIs. He also recorded a career-high .545 slugging percentage. Despite his offensive output, the Athletics failed to defend their Association title. The team finished in seventh place with a 61-46 record in the 13-team league, 14 games behind the champion New York Metropolitans.26

After the disappointing finish in 1884, the first real signs of unrest among the Athletics’ triumvirate ownership group became apparent. In November Lew Simmons announced that he was taking over as field manager in 1885 because the team had lost $20,000 in 1884. He blamed Stovey for the team’s slump. Simmons cited an incident in which he asserted that Stovey arrived at the ballpark too drunk to play, a common-enough claim in the 1880s. In fact, there were numerous reports of heavy drinking among the Athletics, and the owners expressed concerns about almost all their players. The club imposed rules that among other things addressed the problems of hard living associated with the team and the American Association.27 However, the upstanding Stovey was never linked to the social ills that plagued the Athletics.

But co-owners Sharsig and Mason were quick to come to Stovey’s defense, praising him for his performance on the field and his leadership. Stovey defended himself in a letter to Sporting Life. The letter read:

Dear Sir:

In your last issue you published an interview with Lew Simmons, in which that individual expresses himself altogether too freely concerning the occurrences of the past season, and in which he particularly singles me out as an “awful example.” Permit me to say that Mr. Simmons is so bold in his utterance because he knows I am at a safe distance and cannot just now defend myself, and he embraces the opportunity to assail me. I wish to say that the scaffold accident did really happen at the time mentioned, and that 1 was really injured by the falling of the same can be easily proven. I was not intoxicated, as Mr. Simmons states, and I beg that you will do me the favor to publish this public contradiction. I shall shortly have a personal interview with my “friend” Mr. Simmons, concerning this matter.

He says he is going to be the manager next season, and further that he will make the boys play ball or he will fine and expel them. I think he is “shooting off his mouth” altogether too previously, and a short experience will convince him that that is not the way to get good work out of his men, for they cannot and will not play with any heart under apprehension of being fined for every error they make. In my estimation he will make what I may call, in the expressive slang of the day, a “dub” of a manager; and I will frankly state right here that I would prefer my release to playing under him. Trusting that I have not encroached too much upon your valuable space,

I remain. Very truly yours,

HARRY D. STOVEY28

The end result was that Stovey was appointed manager-captain for the 1885 season and Simmons was, albeit temporarily, relegated to low man on the ownership’s totem pole.

Stovey established two significant milestones in 1885. In a game on July 16 at Sportsman’s Park I, Stovey hit the 45th home run of his career, off the Browns’ Jumbo McGinnis. The two-run clout made him the major-league career leader in home runs. On September 28 Stovey hit his final home run of the season, and the 50th of his career, off Pittsburgh Alleghenys rookie hurler John Hofford. Stovey was the first player to hit 50.

Stovey finished the season batting over .300 for the third consecutive year. Playing in a league-leading 112 games, the Athletics’ player-manager finished with a .315 average, 130 runs scored, 27 doubles, 9 triples, 13 home runs, and 75 RBIs. His runs scored and home run totals led the Association. With Stovey at the helm, the Athletics finished in fourth place with a 55-57 record, 24 games behind the champion St. Louis Browns. Stovey never managed a major-league team again and finished his big-league managerial career with a 63-75-2 mark.

On the last day of the 1885 season, Stovey’s older brother John Jr., who had served in the Union Army during the Civil War, died. John, who was unmarried, was buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery, where Stovey’s parents and his sister Sarah would later be buried.29

Desperate to remain competitive in the American Association and with their crosstown National League rivals, the Athletics made another managerial change. Co-owner Simmons, who a year earlier blamed Stovey for the team’s troubles, emerged as the new manager to start the 1886 season. The team was mired in sixth place with a 41-55 record before co-owner Sharsig stepped in to lead the team to a 22-17 finish over its last 39 games. The team finished in sixth place.

Stovey’s offensive production dipped in 1886. Splitting time between center field, right field, and first base, he batted .294 with 28 doubles, 11 triples, and 7 home runs. But the 29-year-old Stovey led the Association with 68 stolen bases in the first in which stolen bases were an official statistic.

For 1887 the Athletics turned to Stovey’s first manager at Worcester, Frank Bancroft. The addition of Bancroft had little impact on team’s success. The Athletics had a record of 26-29 and were in fifth place when the manager was fired and replaced by Mason, the third Athletics owner to manage the team in as many years.

Stovey enjoyed a relatively productive year. In 124 games, the majority in the outfield, he batted .286, scored 125 runs, hit 31 doubles, and stole 74 bases. He hit only four home runs and before the end of the season he was passed by Detroit Wolverines first baseman Dan Brouthers as the leader in career home runs. It was the only season in which Stovey didn’t lead the American Association in at least one major offensive category.30

On August 2 Stovey lost another member of his family. John Sr., Stovey’s father, succumbed to a heart attack at the age of 77.31

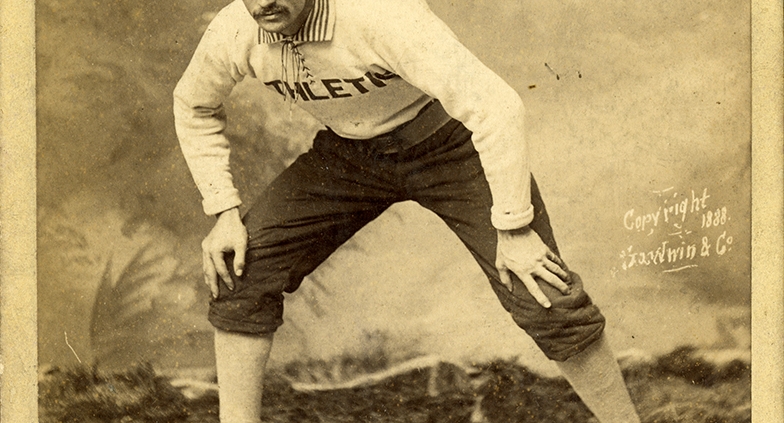

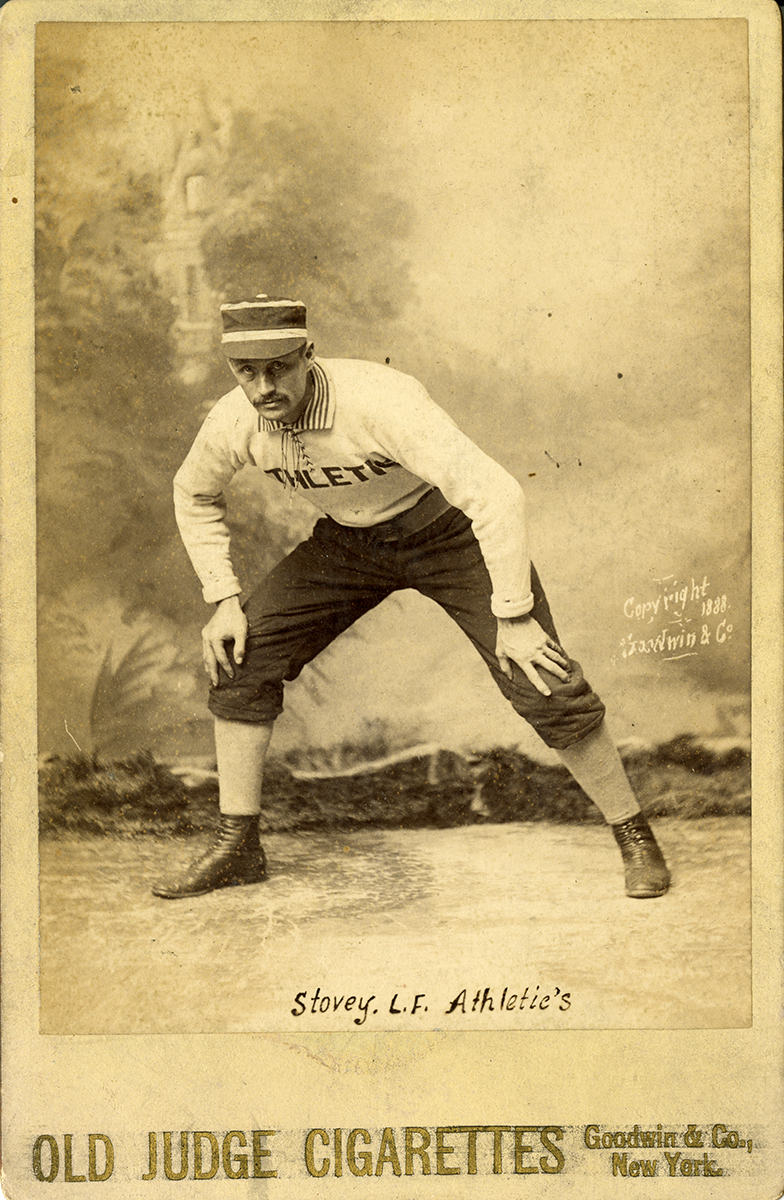

The Athletics’ revolving door of managers continued as Sharsig returned to guide the team in 1888. Stovey was the everyday left fielder for the 81-52 Athletics, who finished in third place 10 games behind the St. Louis Browns. Stovey finished with a .287 batting average, 127 runs scored, 25 doubles, a league-leading 20 triples, 9 home runs, 65 RBIs, and 87 stolen bases. On May 15 he hit for the cycle in a 12-3 victory over Baltimore Orioles.

That season the strong-armed Stovey participated in a long-distance throwing contest sponsored by the Cincinnati Enquirer. Stovey’s heave of 123 yards 2 inches on the fly was good enough for second place, behind Ned Williamson,32 who won the competition with a throw of 133 yards 11 inches.33

The Athletics repeated their third-place finish under Sharsig in 1889, a season that was one of Stovey’s finest. Playing all 137 games in left field, he batted .308 and recorded career highs in runs scored (152), doubles (38), home runs (19), and RBIs (119). (His home-run total was considered a greater accomplishment by many baseball historians than Williamson’s 27 in 1884.) Stovey regained the record for career home runs when he slugged his 80th and 81st against Lee Viau at Cincinnati’s League Park on August 13. Stovey joined Charley Jones as the only players to hold the career record for home runs at two different times.

War broke out in major-league baseball after the 1889 season when the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players announced the creation of the Players’ League for the 1890 season. Stovey was a hot commodity and was courted by the new league’s Boston Reds. He found the prospect of playing closer to his wife’s hometown of New Bedford too appealing to pass up and signed with the King Kelly-managed Reds, ending his seven-year stint in the Association.

Despite playing only seven of the circuit’s 10 campaigns, Stovey’s 76 home runs and 883 runs scored are the most in American Association history. He also ranks in the top 10 of nearly every other category, including games played, batting average, slugging percentage, total bases, hits, and stolen bases.

Stovey was the Reds’ everyday right fielder in 1890 and hit .298 with 26 doubles, 13 triples, and 12 home runs, the third highest total in the Players’ League behind Hardy Richardson (16) and Roger Connor (14). He drove in 88 runs, scored 145 runs, and had a career-high 97 stolen bases, helping the Reds to an 81-48 record as the team finished in first place 6½ games ahead of the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders and captured the Players League championship. On September 3 Stovey became the first player to hit 100 home runs when he hit one off former Athletics teammate Jersey Bakley in Boston.

After the collapse of the Players’ League after the 1890 season and the subsequent ratification of the new National Agreement, it was presumed that Stovey would return to the Athletics and resume his record-setting Association career. The new National Agreement stated that “everyone was supposed to return to the teams that had reserved them in 1889.”34 However, an administrative error on the part of the Athletics left Stovey and former Athletics teammate Lou Bierbauer unprotected and declared free agents.

Stovey opted to accept the National League’s Boston Beaneaters’ offer of $4,200 a season, the highest salary of his career.35 The Beaneaters, led by manager Frank Selee, were coming off a fifth-place finish in 1890 and were confident the aging star could help them capture the National League championship.

On April 1, 1891, three weeks before the start of the season, Stovey and his wife welcomed their fourth daughter, Rachel. The infant, who also had a twin sister who was stillborn, did not survive infancy and died on June 6.

Despite the loss of his infant daughter, Stovey played a key role in the Beaneaters’ run to the National League Pennant – his third championship team in three different leagues. Stovey was primarily used as a corner outfielder (39 games in left field and 96 games in right field). In 134 games he hit .279 with a league-leading 20 triples, 16 home runs, 271 total bases, and a .498 slugging percentage. He had a team-leading 95 RBIs and 57 stolen bases.36 It was the last great season of Stovey’s career.

Stovey started the 1892 season in one of the worst slumps of his career, and on June 20 he was released by the Beaneaters. At the time of his release he was hitting an anemic .164 with no home runs and 12 RBIs. Nearly three weeks later, the 35-year-old Stovey was signed by the last-place Baltimore Orioles. On July 21 he repeated his 1884 feat of hitting three triples in a single game during a 10-3 victory over Pittsburgh. In 74 games with the Orioles, Stovey rediscovered his hitting stroke and batted .272 with 4 home runs and 55 RBIs.

Stovey also started the 1893 season slowly. After hitting only .154 in eight games, he was released by Baltimore. Three days later, on May 25, the 35-year-old Stovey signed with Brooklyn Grooms. In 48 games with the Grooms, he hit .251 with one home run and 29 RBIs. Time and injuries had taken its toll on the one-time slugger. On June 8 he hit the final home run of his career in the Grooms’ 7-6 victory over the Browns. It was his 122nd career home run, the major-league high. He played in his last major-league game on July 29.

Stovey’s record lasted until 1895. Stovey was third on the list all-time home run list (behind Roger Connor and Sam Thompson) as late as 1920, the year Babe Ruth began to single-handedly usher in the live-ball era.

His major-league career behind him, Stovey was reunited with King Kelly when he played briefly for Allentown in the Pennsylvania State League. Then he became the player-manager for New Bedford of the New England League.

After retiring from baseball, Harry Stovey ceased to exist. The ex-player resumed use of the name he was born with, Harry D. Stow. In 1895 he joined the New Bedford police force and served for 28 years. While patrolling his beat along the city’s waterfront one day in 1901, Officer Stow spotted a seven-year-old boy who had fallen between two piers and was struggling in the water. He dived in and saved the boy’s life.37 Soon afterward he was promoted to sergeant for bravery and became a captain in 1915. In 1922 his wife of 43 years, Mary, died. He retired from the police force in 1923.

Stovey died at his daughter’s house in New Bedford on September 20, 1937. He was 80 years old. He is buried in New Bedford’s Oak Grove Cemetery next to his wife and two of his daughters, Harriet and Rachel. At the time of his death, few New Bedford residents knew that Officer Stow was Harry Stovey, one of the greatest baseball stars of the nineteenth century.

Whether or not Stovey belongs in the Hall of Fame has been a topic of conversation among baseball historians for years. In 1936 he received six votes for the Hall of fame, the only year he appeared on the ballot. He outpolled both Kid Nichols and Jim O’Rourke, both of whom were later inducted into Cooperstown.38 In 1983 a poll of SABR’s nineteenth century research committee voted Stovey and Pete Browning as the two players of that era most deserving to be in the Hall (excluding those already enshrined).39 In 2011 SABR members selected Stovey as the Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legend.40

Statistically, a strong case can be made for Stovey’s enshrinement in the Hall of Fame. In addition to being an early home-run king – Stovey finished in the top four in home runs 10 times, leading the league in five of those seasons – he was one of the early game’s great doubles and triples hitters. Stovey finished his 14-year major-league career with 348 doubles and 176 triples. He had 912 RBIs, an impressive number considering he often batted in the leadoff position early in his career.

As of 2019, Stovey’s 509 stolen bases ranked 35th all-time. However, no stolen-base statistics exist for the first six years of his career.

Stovey is also one of only three players to have played in a minimum of 1,000 games and averaged more than one run scored per game. Billy Hamilton and George Gore are the others.41 Stovey scored 1,495 runs in 1,489 games, including nine seasons of 100 or more runs scored.

Throughout his career it was often said that Stovey had sure hands and a strong, accurate arm with great range. Statistically, he was an above-average first baseman. He finished in the top four in the league in range factor from 1881 to 1885 and in the top five in fielding percentage during the same years. As of 2019, his 165 career outfield assists placed him in the top 100 all-time.

Modern sabermetrics provide a less definitive case for Stovey’s inclusion in the Hall of Fame. His black-ink and gray-ink scores of 56 and 210, respectively, are favorable.42 Stovey led his league in important offensive categories more than 20 times, including extra-base hits five times, runs scored and triples four times, slugging percentage and total bases three times, stolen bases twice, and doubles and RBIs once. However, his WAR scores are less definitive. Stovey’s career WAR of 45.2 and seven-year peak WAR of 31.1 are considerably below the average of the 20 left fielders in the Hall of Fame as of 2019. The average career WAR and seven-year peak WAR for left fielders are 65.5 and 41.6, respectively.

Stovey’s omission from the Hall of Fame may also be a consequence of revisionist history. Early scoring rules differed and box scores and game accounts offered comparatively little information by today’s standards. Later baseball historians went back and revised the American Association’s statistics, resulting in a lowering of many the jaw-dropping statistics that were once attributed to Stovey.43 This, coupled with the fact that the Association, though recognized as a major league, was considered inferior to the National League, may be one reason why Stovey has yet to be elected to the Hall of Fame.44

Regardless of whether or not Stovey is eventually enshrined in Cooperstown, he should be remembered as one of the early game’s great power hitters and an innovative baserunner who helped revolutionize the national pastime.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Matt Kelly, “19th Century Star Harry Stovey,” baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/pre-integration/stovey-harry Retrieved March 3, 2019.

2 Edward Achorn, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey. (New York: Public Affairs, 2006), 76.

3 US Census Records lists the family as both Stow and Stowe. Some records include the family as both Stow and Stowe in the same census. There may have been other children at some point, but nine appear in census records.

4 “CAST: Liberty Cast and Recast.” Retrieved from castartandobjects.com/blog/2017/7/4/liberty-cast-and-recast

5 Harry first appeared in US Census Records in 1860 with the surname Stow. The surname on the family headstone in Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford, Massachusetts, is Stow. Unhappy with the sound of the bell, Stow and Pass recast the bell as second time in June 1753.

6 “United States Civil War Soldiers Index, 1861-1865,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FS3M-L28 : 4 December 2014), John P. Stow, Corporal, Company E, 90th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry, Union; citing NARA microfilm publication M554 (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 119; FHL microfilm 882,454.

7 Buddy Thomas, “Stovey: City Man Changes the Game,” New Beford Standard-Times, April 8, 2006. southcoasttoday.com/article/20060408/news/304089946.

8 A cooper is a person trained to make wooden casks, barrels, vats, buckets, tubs, troughs, and other staved containers.

9 Matt Kelly, “19th century star Harry Stovey.” Retrieved from baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/pre-integration/stovey-harry.

10 There are multiple records of the Stoveys’ marriage. One lists the date as July 21 and others as July 23.

11 “Diamond Dust Early Blown,” Boston Globe, January 16, 1881: 2.

12 Benjamin McArthur, Actors and American Culture, 1880-1920 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984): 7-11, cited by Charlie Bevis in “Frank Bancroft,” SABR BioProject. Retrieved from sabr.org/bioproj/person/48535bb7.

13 Charlie Bevis, “Worcester Nationals ownership history,” Retrieved from sabr.org/research/worcester-nationals-ownership-history.

14 Philip Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 243.

15 Achorn, 77.

16 Stolen bases did not become an official statistic until 1886.

17 Peter Morris. Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball. New, Revised and Expanded One-Volume Edition. (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 188.

18 Alfred Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Company, 1910), 186.

19 Achorn, 226.

20 Achorn, 226-227. Some accounts of the game report that Stovey scored the winning run on a wild pitch. According to his obituary in The Sporting News, he single-handedly sealed the championship for the Athletics in the final game of the season against Louisville when, in the 10th inning, he singled, stole second, went to third on an infield out, and scored on a wild pitch thrown by pitcher Guy Hecker.

21 Achorn, 240.

22 Ibid.

23 William McNeil, The King of Swat: An Analysis of Baseball’s Home Run Hitters from the Major, Minor, Negro and Japanese Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1997), 36.

24 Williamson’s 27 home runs in 1884 were largely attributed to the fact that in White Stocking Park (a.k.a. Lake Front Park), the field’s dimensions were 180 feet down the line to left, 280 feet to left-center, 300 feet to dead center field, 252 feet to right-center, and 196 feet down the line to right. The right-handed-hitting Williamson hit 25 of his 27 home runs at White Stocking Park and never hit more than nine home runs in any other season.

25 As of 2019 only 11 major-league players had hit two triples in one inning. The feat was most recently accomplished by the Colorado Rockies outfielder Cory Sullivan on April 9, 2006.

26 The American Association expanded to 13 teams for the 1884 season. The league contracted back to eight teams in 1885 and then played its final two seasons (1890 and 1891) with nine teams.

27 Paul Hofmann, “Jud Birchall,” SABR BioProject. Retrieved from sabr.org/bioproj/person/8ab5cdb7.

28 Harry Stovey, “Harry Stovey Expresses Himself,” Sporting Life, December 3, 1884: 3.

29 “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JNLH-M3F : March 8, 2018), John P Stow, 09 Oct 1885; citing 797, Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; FHL microfilm 2,070,684.

30 John Shiffert, Base Ball in Philadelphia: a History of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 132.

31 “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JKS5-M3X : 8 March 2018), John P. Stow, 02 Aug 1887; citing 257, Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; FHL microfilm 2,078,809.

32 George Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club: A Concise and Accurate History of Base Ball from Its Inception (Boston: M.F. Quinn & Co., 1897), 217.

33 “Baseball Records: Long Distance Throwing,” World Almanac 1892: 227.

34 Shiffert, 153.

35 Thomas. After his retirement, Stovey claimed he never earned more than $2,400 per year playing baseball.

36 Billy Nash also recorded 95 RBIs to tie for the team lead.

37 Achorn, 245.

38 David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League: The Illustrated History of the American Association – Baseball’s Renegade Major League, (New York: Lyons & Buford, Publishers, 1994): 238.

39 Lew Lipset, “Grandpa Was Harry Stovey,” The National Pastime, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Cooperstown, New York: Society for American Baseball Research, Winter 1985): 84.

40 “Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legends.” Retrieved from https://sabr.org/overlooked-19th-century-baseball-legends. Browning was selected in 2009 and Deacon White, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2013, was selected in 2010.

41 Gabriel Schechter, “Harry Stovey: Forgotten Five-Tool Star,” The National Pastime Museum, May 9, 2013. Retrieved from thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/harry-stovey-forgotten-five-tool-star.

42 The Black-Ink Test is named so because league-leading numbers are traditionally represented with Boldface type. The score is a measure of how often a player led the league in a variety of “important” stats. Similarly, the Gray-Ink test measures a player’s appearance in the top 10 of the league in “important” stats. It is important to note that Stovey played during an era when 8 to 10 teams were typically the norm. These two comparative measures disadvantage modern players who played in 14- to 16-team leagues.

43 For decades after his retirement, Stovey was credited with having a career batting average of .321 and setting the single-season stolen-base record of 156 in 1888.

44 Schechter.

Full Name

Harry Duffield Stovey

Born

December 20, 1856 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

September 20, 1937 at New Bedford, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.