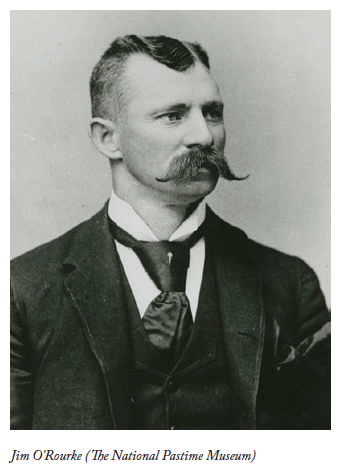

Jim O’Rourke

During a playing career that spanned a remarkable six decades, Jim O’Rourke did much to advance baseball as our national pastime. A key member of championship teams in both the National Association and the National League, O’Rourke was a versatile performer in the field and a reliable .300 hitter at the plate. Thereafter, as his playing days wound down, O’Rourke assumed the role of baseball executive, particularly in his native Connecticut, where he established a thriving minor league. O’Rourke was also a figure of some cultural significance, rising to prominence in an era when anti-Irish prejudice still flourished in many quarters. Unlike the stereotypical brawling, hard-drinking wastrel of King Kelly stripe, O’Rourke was a sober, well-educated ballplayer whose dignified bearing both on and off the diamond was punctuated only by a proclivity for grandiloquence. In time, these rhetorical flights of fancy, which amused and bewildered his contemporaries, gave rise to the moniker by which Jim O’Rourke is known to this day: Orator.

During a playing career that spanned a remarkable six decades, Jim O’Rourke did much to advance baseball as our national pastime. A key member of championship teams in both the National Association and the National League, O’Rourke was a versatile performer in the field and a reliable .300 hitter at the plate. Thereafter, as his playing days wound down, O’Rourke assumed the role of baseball executive, particularly in his native Connecticut, where he established a thriving minor league. O’Rourke was also a figure of some cultural significance, rising to prominence in an era when anti-Irish prejudice still flourished in many quarters. Unlike the stereotypical brawling, hard-drinking wastrel of King Kelly stripe, O’Rourke was a sober, well-educated ballplayer whose dignified bearing both on and off the diamond was punctuated only by a proclivity for grandiloquence. In time, these rhetorical flights of fancy, which amused and bewildered his contemporaries, gave rise to the moniker by which Jim O’Rourke is known to this day: Orator.

He was born James Henry O’Rourke in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on September 1, 1850.1 He was the second of three children surviving to adulthood born to Hugh O’Rourke and his wife, Catherine (nee O’Donnell), Irish Catholic immigrants from County Mayo who arrived in Bridgeport around 1845.2 Jim’s youth was spent attending local schools, working on the small family farm, and playing baseball, often with older brother John, himself destined to become a major leaguer. A right-handed thrower and batter, young Jim O’Rourke began his formal playing career in 1866 as a member of the Bridgeport Ironsides, a recreational team for boys 12 to 15 years old. The following summer, he played for the Unions, another local youth team. In 1868 Jim advanced to the Stratford Osceolas, a top-notch semipro team for which he saw duty mostly as an outfield substitute.3

O’Rourke’s ascension in baseball ranks was temporarily stalled by the untimely death of his father in December 1868.4 Staying close to home to assist on the family farm, he returned to the Unions for the 1869 season. In 1870 he was back with the Stratford Osceolas as an outfield regular and backup catcher, his name often appearing as Rourke in print accounts and box scores of Osceolas games. That year, an otherwise successful season ended on a down note when the Middletown Mansfields swept Stratford to win the championship of Connecticut. But a season later, the Osceolas returned the favor, upsetting Middletown in a state championship rematch.5

In 1872 the Middletown Mansfields, entering the one-year-old National Association, sought to upgrade their roster by signing the Stratford battery of O’Rourke and pitcher Frank Buttery. According to popular lore, O’Rourke’s joining the Mansfields was conditioned upon the team procuring a replacement to perform his chores on the O’Rourke farm.6 Shortly after the season began, O’Rourke also took on the responsibilities of husband, marrying sweetheart Anna Kehoe, a recent arrival from Ireland. While the marriage would prove a long and happy one, the same could not be said of the O’Rourke experience with the Middletown Mansfields. A small-bore operation with shaky financial underpinnings, the Mansfields posted a 5-19 log in the National Association before the team folded in mid-August. Jim thereupon returned to the farm in Bridgeport.

Although he had batted only a modest .273 while alternating between shortstop and catcher for Middletown7, O’Rourke had made a favorable impression in National Association circles. In December 1872 he was invited to join the Boston Red Stockings by team leader Harry Wright, renowned for his stewardship of a Cincinnati nine that had gone undefeated during an 1869 nationwide tour. With Annie now pregnant with the first of the eight O’Rourke children, Jim accepted – but only after receiving written assurance from Wright that his salary was guaranteed by club backers.8 An early photograph of him in Boston colors depicts the 5-foot-8 O’Rourke standing erect in the batter’s box and already sporting the luxuriant handlebar mustache that would become his personal trademark. Under the tutelage of Wright, a seminal baseball strategist and a man of principle9, the 22-year-old O’Rourke blossomed, hitting a robust .350 for a 43-16 Red Stockings pennant winner.

O’Rourke’s sophomore season in Boston (which saw him moved to first base) was a solid one. He posted a .314 batting average with a league-leading five home runs as the Red Stockings breezed to a second consecutive league crown. The highlight of the 1874 campaign, however, was a midseason exhibition tour of Great Britain. There, O’Rourke’s powerful arm won him a distance throwing contest10. He also displayed a surprising natural aptitude for the national game of the host country, cricket11. Apart from overseas adventure and continued good play, the 1874 season also saw the first incidence of a recurring event in the O’Rourke career: difficulty with management. Jim rebelled against club owners’ attempt to recoup the purported financial loss incurred by the Great Britain trip via $100 assessments on Red Stockings players. Eventually Harry Wright persuaded O’Rourke to accept the deduction from his paycheck. But resolution of the dispute marked the first, last, and only time that Jim O’Rourke would capitulate in a fight with his baseball employers.

The 1875 season would see the Boston Red Stockings at the zenith of their success and the five-year-old National Association at the end of its run. Alternating between the outfield and catching, O’Rourke had a mixed year offensively. He batted a somewhat off .296 but led the Association in home runs (6) while finishing third in runs scored (97) and RBIs (72). With four of the circuit’s five top batsmen (Deacon White .367; Ross Barnes .364; Cal McVey .355, and George Wright .333) and A.G. Spalding posting an incredible 54-5 log on the mound, the Red Stockings (71-8) waltzed to the 1875 pennant, 18½ games ahead of second-place Hartford. At season’s end, however, the Boston team was gutted, with stars Spalding, White, Barnes, and McVey defecting to Chicago. Shortly thereafter, the National Association disbanded, replaced by a new, owner-dominated circuit, the National League.

Despite expectations to the contrary, Jim O’Rourke did not join his former teammates in Chicago. Nor would he sign with the National League franchise in Boston, holding out for a salary increase as Opening Day 1876 approached12. This time, it was club management that caved in, inking O’Rourke to a $1,600 pact that doubled his previous salary.13 The signing came just in time for Jim to hustle to Philadelphia for the team’s National League debut. There, a first-inning single off Athletics pitcher Lon Knight accorded O’Rourke the distinction of recording the first base hit in National League history. During that inaugural season, Jim amply repaid his employers’ largess, playing in all 70 league games and batting a team-leading .327. But the Boston Red Caps (as the team was now called) were no match for the star-laden Chicago club, which captured the first National League flag handily. Red Caps fortunes – and the course of baseball history –underwent a change in December 1876. Ascending to the club presidency at the winter meeting of team stockholders was Arthur H. Soden, a prosperous roofing contractor and baseball enthusiast. For the next 30 years, the aloof and tough-minded Soden reigned over the franchise, marshaling the talent that brought eight championships to Boston while spearheading team owner efforts to curtail player freedom of movement and salaries.14

In 1877 O’Rourke had a breakout season, batting a career-high .362 while pacing the National League in runs scored (68), walks (20), and on-base percentage (.407). He was among the leaders in hits, total bases, and slugging percentage. With first baseman Deacon White returned to Boston and leading the league in most of the other offensive categories, and pitcher Tommy Bond posting all but two of the team’s 42 victories, the Red Caps rallied to capture the pennant – an achievement subsequently diminished by the discovery that players from the second-place Louisville club had dumped crucial late season games.15 The 1877 season also occasioned the first of Jim O’Rourke’s clashes with team boss Soden. With many National League franchises operating in red ink, the league had imposed a $30 fee for uniforms on the players. O’Rourke refused to pay it and, after much wrangling, Soden relented, exempting him from the charge. The following season, Soden levied a $20 charge on his players for laundering their uniforms while they were on the road. And again, O’Rourke balked at paying the charge, precipitating another dispute with Soden.16 Jim also had his problems between the foul lines in 1878, slumping to .278 with reduced run production. Still, Boston managed a successful pennant defense, its 41-19 record four games better than that of runner-up Cincinnati.

Unhappy in Boston, O’Rourke joined Red Caps mainstay George Wright in a move to Providence for the 1879 season. Once with the Grays, O’Rourke quickly regained his batting stroke. His .348 batting average and 126 hits were second only to the league leader, teammate Paul Hines (.357 and 146), while Jim’s .371 on-base percentage was the league best. More importantly, O’Rourke and his mates had the satisfaction of winning the pennant, their 59-25 record five games better than that of a Boston nine that featured a standout rookie outfielder named John O’Rourke.17 Shortly after the 1879 season ended, the league’s magnates adopted the first version of the reserve clause, a contractual restraint that bound five designated players from each team to the club they had played for the previous season. The owners of the Providence club, however, chose not to reserve Jim O’Rourke for the 1880 campaign. And Jim, anxious to play alongside his older brother, signed with Boston, his previous difficulties with team owner Soden notwithstanding. Sadly, the season was a disappointment to all concerned. John, seriously shaken up in a late-May crash into the outfield fence at Troy, saw his batting average plummet 66 points from the previous season’s .341 and posted reduced numbers across the board. Jim also had an off year, matching his brother’s .275 batting average but with a league-leading six home runs. Arthur Soden, meanwhile, had to endure a sixth-place finish for his Boston team and the reduced revenue at the gate that came with it.

Boston placed neither O’Rourke on its reserved list for the 1881 season, and the brothers were soon entertaining offers from other National League clubs. But John, now 32 years old, chose the security of a position with the New Haven Railroad over another diamond campaign.18 Jim, meanwhile, joined the Buffalo Bisons as playing captain/manager. Under O’Rourke’s direction, the club, a sad-sack 24-58 the previous season, posted a respectable 45-38 record. Like that of the franchise, Jim’s own performance rebounded. Playing mostly third base, he batted .302 with 71 runs scored, fourth best in the league. The 1881 season also featured delivery of perhaps the most celebrated exemplar of O’Rourke grandiloquence. In response to a request by shortstop Johnny Peters for a $10 advance on his salary, the Orator replied:

“The exigencies of the occasion and the condition of our exchequer will not permit anything of that sort at this period of our existence. Subsequent developments in the field of finance may remove the present gloom and we may emerge into a condition where we may see our way clear to reply in the affirmative to your exceedingly modest request.”19

Dealing with cash-strapped players fell to O’Rourke because, in addition to leading the team on the field, he also performed the tasks of club bursar, traveling secretary and prefect of discipline. A number of the pleasure-seekers on the Buffalo team – most notably mound stalwart Pud Galvin – chafed under the governance of their chief, a nondrinking, nonsmoking taskmaster who took his leadership responsibilities very seriously.20 But like him or not, the Bisons continued their competitive play under O’Rourke, posting winning records in both the 1882 and 1883 seasons, if not challenging for the National League pennant. Nor did the press of his off-field obligations appear to take a toll on O’Rourke. For on July 3, 1883, he appeared in his 319th consecutive game, setting a new league standard. By mid-September, Jim was near the close of a season that would see him hit .328. Then tragedy struck. On September 15, 1883, second daughter Anna died from a sudden illness. She was only 9 years old. Upon receiving the news, a grief-stricken Jim O’Rourke immediately left the team for the funeral in Bridgeport. Four days later he returned to Buffalo to guide the Bisons to the finish of a 52-45 campaign.

During his time in Buffalo, O’Rourke, an implacable foe of the reserve clause, had operated without one in his contract. Rather, he and the club owners proceeded under a yearly gentleman’s agreement that O’Rourke would maintain allegiance to the Bisons franchise. But in the spring of 1884 Jim served notice that this would be his last season in Buffalo. Despite his impending departure, he continued to serve the club diligently. Before the season’s start, he alleviated playing-field problems by locating more suitable grounds and superintending the construction of Olympic Park, a handsome new venue for the Bisons. O’Rourke then led the team on the field by example, batting .347 and pacing the National League with 162 base hits.21 At season’s end the Bisons were in third place, their 64-47 record closing the O’Rourke ledger as Buffalo field leader with a four-year mark of 206-169 (.549).

The year 1885 proved a watershed in the professional life of Jim O’Rourke. After Anna’s death he was determined to find a club close enough to Bridgeport to allow him to spend Sundays at home with the ever-expanding O’Rourke brood.22 Using a bidding war among interested teams to his advantage, Jim extracted a $4,000 contract from the New York National League club. He also negotiated the now standard player reserve clause out of his 1885 deal. In New York O’Rourke joined the Hall of Famers – Buck Ewing, John Montgomery Ward, Tim Keefe, Roger Connor, and Mickey Welch – being aggregated by team owner John B. Day and manager Jim Mutrie23 and reached the pinnacle of his playing career. His time in New York had other ramifications as well. He formed a close and lasting friendship with Connor, a fellow Connecticut (Waterbury) Irishman as taciturn as O’Rourke was loquacious. After their major-league days were over, the two played pivotal roles in the establishment of minor-league ball in their home state. Of perhaps more consequence, the signing with New York reunited O’Rourke with former Providence teammate Ward, a baseball visionary who would shortly put into practice the fundamental employment principles that O’Rourke held dear. In the fierce Players League War to come, O’Rourke (and Tim Keefe) would serve as commander Ward’s primary lieutenants. In the short term, however, the reconnection to Ward had more immediate effect. Emulating Ward’s example, Jim enrolled in law school during the offseason, his tuition at Yale being underwritten by the Giants.24 In time the practice of law would provide a congenial outlet for the Orator’s delight in speech.

The 1885 New York Giants ran roughshod over the opposition, posting an 85-27 record. Its .759 winning percentage is the highest ever recorded by a major-league team – that finished in second place. With Cap Anson, John Clarkson, and the irrepressible King Kelly at the peak of their Cooperstown-bound careers, the Chicago White Stockings (87-25) were two games better than New York. Still, the season was a good one for O’Rourke. He batted .300, with 119 runs scored and a league-best 16 triples. But trouble for O’Rourke and his playing brethren was on the horizon.

Shortly after the 1885 season was over, National League magnates adopted a $2,000 ceiling on player salaries. Within days the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players was formed, with Giants Ward, O’Rourke, and Keefe being the prime movers in this new union movement.25 New York owner Day, an outspoken opponent of the salary ceiling, promptly ignored it, signing O’Rourke to a $3,000/no-reserve-clause contract for the 1886 season. Other club bosses likewise disregarded the ceiling. But the well of magnate/player relations had been poisoned, with consequences that would manifest themselves in due course. In the meantime, Jim O’Rourke continued his dependable play in a Giants uniform, batting .309 and patrolling center field when not spelling Buck Ewing behind the plate. But in 1887, a walks-as-hits-inflated .344 batting average did not camouflage a fall-off in the performance of the now 37-year-old O’Rourke.26 Nor was the team maintaining standards, having slid to fourth place. Indeed, for Jim O’Rourke the year’s highlights occurred mostly away from the diamond: graduation from Yale Law School in June, followed by his passing the Connecticut bar examination and admission to the practice of law on November 5, 1887.27

In 1888 a resurgent Giants nine, with relatively minor contribution from a .274 hitting O’Rourke, captured the National League crown, their 84-47 record nine games superior to that of the runner-up White Stockings. The Giants then claimed the title world champions, defeating the American Association St. Louis Browns in a postseason match of league standard-bearers, but again with little help from O’Rourke (.222/1 RBI in 10 games). But suspicions that the Orator was finally slowing down were confounded during the 1889 campaign. Jim’s .321 batting mark included 46 extra-base hits and, although never swift afoot, the 39-year-old also managed to steal 33 bases. The Giants, meanwhile, repeated as world champions, nipping Boston at the wire for the National League pennant and then besting the Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the American Association in a “World Series” that saw Jim O’Rourke bat a robust .389, with two homers and seven RBIs.

The success of the 1889 Giants’ season had been accompanied by simmering player discontent in New York and elsewhere. Long resentful of the reserve clause, the players were further aggrieved by the implementation of a rigid salary-classification scheme by National League club owners. Shortly after the 1889 baseball championship had been decided, the players struck back, announcing the formation of an employee-controlled major-league operation, the Players League. The brainchild of John Montgomery Ward, the new circuit would raise havoc on the baseball scene, successfully recruiting virtually all the front-line players in the National League and a number of American Association standouts as well. The Giants were particularly hard-hit, losing their entire lineup save for aging pitcher Mickey Welsh and outfielder Mike Tiernan, to the Players League. A combative John B. Day retaliated by seeking injunctive relief against Ward, O’Rourke, Keefe, and Ewing, but to no avail. Jim and the others prevailed in court and, except for Ward, player-manager of the Players League team in Brooklyn, commenced the 1890 season playing for the Players League Giants in a new ballpark (Brotherhood Field) separated from the National League operation in the New Polo Grounds (later Manhattan Field) by no more than a ten-foot-wide alley and the stadium walls.

Playing for the Ewing-led Big Giants, Jim O’Rourke registered exceptional numbers during the 1890 season. In addition to a .360 batting average, the 40-year-old posted career-best figures in hits (172), doubles (37), home runs (9), RBIs (115), slugging (.515), and on-base percentage (.410), all achieved while playing in only 111 games. O’Rourke’s performance, however, was not duplicated by his team (third place). Nor did the Players League prosper as a whole. In fact, the season had been a catastrophe for the new circuit’s financial backers. That fall they were outmaneuvered in peace settlement negotiations by A.G. Spalding, the hard-nosed de-facto leader of the National League, and bluffed into dissolving the Players League. In New York, National League owner Day and his Player League counterparts merged operations, precipitating the return of O’Rourke and others to their former club. 28 By virtue of the terms of the consolidation agreement, O’Rourke also became a small shareholder in the reconstituted New York Giants franchise. He then resumed his post in the Giants’ outfield, posting respectable batting averages for the 1891 (.295) and 1892 (.304) campaigns.

Jim O’Rourke’s tenure as a New York Giant ended on a sour note. Late in the 1892 season manager Pat Powers began cleaning house. Among the veterans released by the Giants was the 42-year-old O’Rourke, his contract assigned to Washington for the 1893 season, As recounted by one Giants historian:

“O’Rourke was outraged. In a clubhouse scene, he denounced Powers as a fool who was running the team into the ground. John Day, supporting his manager, suspended O’Rourke for insubordination and outrage to authority. After thinking it over, the Orator apologized to Powers and was reinstated. But he did not return to the lineup.29

His association with the Giants severed at season’s end, O’Rourke assumed the post of player-manager for the Washington Senators, a former American Association franchise admitted to the National League in 1892.30 Appearing in all but one of the Senators’ 130 games, O’Rourke batted a creditable .287, with 95 RBIs. But his supporting crew was hapless, the team’s last place 40-89 finish prompting the release of manager O’Rourke and the end of his career in the major leagues. Including the one-year debacle in Washington, manager Jim O’Rourke posted a 246-258 (.488) record in five seasons as a major-league field leader. Far more distinguished were his accomplishments as a player: a .313 batting average over 22 seasons in the National Association, National League, and Players League, with 2,678 base hits31, the most of any 19th-century big-league ballplayer not named Anson. He had also been a member of eight league champion teams.

With his major-league career over, O’Rourke returned to Bridgeport, where he practiced law and oversaw his real-estate interests. But he was unable to get baseball out of his system. A brief turn as a National League umpire during the 1894 season gave O’Rourke a taste of the abuse that the men in blue were forced to endure. By mid-June he had had enough, pronouncing the duties of an umpire “too trying” for him to continue32. Thereafter, he again took to the field as a player, making appearances for the St. Joseph T, B&L Association, a crack semipro team that played near home. Long active in parish and civic affairs, Democrat O’Rourke stood for election to the Connecticut legislature that fall but fell victim to the Republican landslide that swept the nation.33 In 1895 he attempted to organize a professional league in Connecticut but the effort was stillborn. His newly formed Bridgeport Victors team was therefore obliged to play as an independent, with O’Rourke himself in uniform for eight of its games.34 More noteworthy than his own play, however, was O’Rourke’s engagement of Harry Herbert, a black outfielder and Bridgeport resident who would spend the next four seasons playing for O’Rourke teams.35

In 1896 Jim assembled eight Connecticut teams into the Naugatuck Valley League. With its 46-year-old catcher-manager leading the way with a .437 batting average, the Victors captured the league pennant. Reorganized once again and renamed the Connecticut State League, the circuit soon included a team from Waterbury sponsored by old O’Rourke teammate and friend Roger Connor.36 For the next eight seasons Jim O’Rourke’s name would regularly appear in the Bridgeport lineup, the team renamed the Orators in 1898 in his honor. In addition to his role as player, manager, and chief league official, O’Rourke subsequently became active in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, a minor-league protective organization that he helped found in 1902. As if the above were insufficient to occupy his time, O’Rourke also attended to various local responsibilities. From 1901 to 1903, he was a Bridgeport fire commissioner, a post that often brought him into heated disagreement with Denis Mulvihill, the city’s hard-drinking mayor. As reported by O’Rourke authority Bernard Crowley, “On occasion, police intervention was needed to end their debates.”37 Later O’Rourke served on the Bridgeport Paving Commission. He was also an active member of the Royal Arcanum, the Connecticut Bar Association, the Bridgeport Elks, and the Knights of Columbus.

In 1903 a proud O’Rourke was joined in the Orators lineup by his son Jimmy, an infielder who later played for the New York Highlanders.38 The following season, 54-year-old Jim O’Rourke, still the regular Bridgeport backstop, appeared in his 1,999th and final major-league game. With the New York Giants on the verge of their first pennant since 1889, manager John McGraw summoned O’Rourke, the last active member of that old championship team, to catch the title clincher. And the old warrior did not disappoint, handling Joe McGinnity over all nine innings of a 7-5 victory over Cincinnati.39 He even went 1-for-4 at the plate.40

In 1903 a proud O’Rourke was joined in the Orators lineup by his son Jimmy, an infielder who later played for the New York Highlanders.38 The following season, 54-year-old Jim O’Rourke, still the regular Bridgeport backstop, appeared in his 1,999th and final major-league game. With the New York Giants on the verge of their first pennant since 1889, manager John McGraw summoned O’Rourke, the last active member of that old championship team, to catch the title clincher. And the old warrior did not disappoint, handling Joe McGinnity over all nine innings of a 7-5 victory over Cincinnati.39 He even went 1-for-4 at the plate.40

Before the 1906 season, Connecticut State League President James H. O’Rourke, erstwhile nemesis of player salary limitations, announced that the league’s $1,800 ceiling on player salaries “will be strictly enforced” by the league office.41 O’Rourke himself remained the everyday catcher (93 games) for the Orators that season but thereafter his playing time began to dwindle. Still, in January 1910 he told a reporter that the secret to his perpetual youth and vigor was “baseball. It is the real elixir of life.”42 But shortly thereafter, he gave up the Bridgeport franchise, selling the club to H. Eugene McCann, a friend who had once managed a minor-league team in Jersey City.

Baseball was not the only thing taking a smaller place in Jim O’Rourke’s life. His children were now mostly married and out of the house. So was his mother, Catherine O’Donnell O’Rourke, who had died in 1907, aged about 85. But the real blow came on June 14, 1910, when Annie, Jim’s wife of 38 years, died from the lingering complications of a fall. A year later that loss was compounded by the death of brother John, felled by a heart attack while handling baggage on a Boston railway platform. Jim endeavored to fill the void by remaining engaged in the affairs of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players and the Connecticut State League. And on September 14, 1912, Connecticut State League president O’Rourke donned the pads a final time, catching nine innings for the New Haven Wings in a game against Waterbury. He was then 62 years old.

Jim’s last years in baseball were not happy ones. In February 1916 he lost a protracted battle with New England League President Tim Murnane over the direction of minor-league baseball in the region. Among the casualties of the New England Baseball War was an O’Rourke/Murnane friendship that dated to when the two had been young teammates on the Stratford Osceolas. Withdrawing from Organized Baseball, Jim devoted his remaining years to his law practice and doting on his grandchildren. He also remained busy with parish and professional duties, serving on the executive committee of the Park City Knights of Columbus World War I fund and handling matters as a member of the National Board of Arbitration.

On New Year’s Day 1919, O’Rourke braved a blizzard to consult a client and then caught a severe cold on the walk home from his office. Pneumonia quickly set in. He died seven days later, aged 68 and deeply mourned in the Bridgeport community. A locally published obituary extolled him as “a kindly father, a splendid citizen, a true friend,” and a man who would be remembered by baseball fans for “his great skill as an exponent of the national game.”43 After a funeral Mass at St. Mary’s Church, Jim’s remains were buried in the family plot at St. Michael’s Cemetery in nearby Stratford. He was survived by his seven children and his sister, Sarah O’Rourke Grant.

In 1945 the memory of Jim O’Rourke was permanently preserved via his enshrinement in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. His Cooperstown plaque tersely summarizes his career but is far too small to reflect the scope of his contributions to the game. As a pioneer player, union organizer and early minor-league executive, James Henry “Orator” O’Rourke was an exemplary figure, one eminently worthy of baseball’s highest accolade.

This biography is included in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources specifically cited in the notes below, the following works were consulted during the preparation of this profile:

Marty Appel, Slide, Kelly, Slide: The Wild Life and Times of Mike “King” Kelly, Baseball’s First Superstar (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999).

Christopher Devine, Harry Wright: The Father of Professional Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003).

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

David Nemec, The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: David I. Fine Books, 1997).

Harold Seymour (with Dorothy J. Mills), Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1960).

David Stevens, Baseball’s Radical for All Seasons: A Biography of John Montgomery Ward (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1998).

The writer is indebted to O’Rourke experts Mike Roer and Bernie Crowley for their generous assistance in the preparation of this profile.

Notes

1 O’Rourke himself usually gave his birthday as August 24 and early biographical sketches often have him born in 1852 or 1854. The September 1, 1850, birthday given above as well as other biographical information about O’Rourke is derived from various US censuses, material contained in O’Rourke’s file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York, and, especially, Mike Roer’s thorough and informative biography Orator O’Rourke, The Life of a Baseball Radical (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), and the O’Rourke family genealogical chart accessible at www.MikeRoer.com. E-mails from O’Rourke expert Bernard Crowley also provided the writer with helpful information on the O’Rourkes.

2 Roer, 8. Jim’s siblings were brother John (1849-1911) and sister Sarah (1854-1931). An elder brother named Patrick (1837-1852) died when Jim was a toddler and other O’Rourke children, now lost to history, may not have survived infancy.

3 Roer, 8-16.

4 Hugh O’Rourke, a farmer and part-time night watchman, died of tetanus on December 31, 1868, about age 56. Cause of death per e-mail from Bernie Crowley to the writer, dated October 10, 2011.

5 Roer, 17-24.

6 Ibid., 25-26. O’Rourke’s salary for the 1872 season was $500.

7 Statistics cited in this profile are taken from www.baseball-reference.com.

8 For almost a century, no account of the O’Rourke signing with Boston was complete without reference to Wright’s alleged request that Jim drop the O’ from his surname, lest offense be given to the “Puritan” backers of the Red Stockings club. To this, Jim gallantly replied that he “would rather die than give up my father’s name. A million dollars would not tempt me.” See e.g., the O’Rourke obituary in the Bridgeport Evening Post, January 9, 1919, or Bernard J. Crowley, “James Henry O’Rourke,” in Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: SABR, 1996), 324. O’Rourke’s biographer, however, suspects the anecdote is apocryphal, tracing its print origins to a 1906 column by Boston sportswriter (and former O’Rourke teammate) Tim Murnane. See Roer, 33. The writer is also skeptical, as the business entrepreneur/sportsmen who backed the Boston club (Ivers Adams, John Conkey, N.T. Apollonio, et al.) were hardly Puritan or Boston Brahmin types. And whatever anti-Irish prejudice they may have harbored privately would have been more than offset by the financial attraction of drawing the city’s burgeoning Irish population to the ballpark. Perhaps to that end, the 1873 Boston Red Stockings would occasionally feature an all-Irish-Catholic outfield, with O’Rourke in center flanked by Andy Leonard and Jack Manning.

9 During the 1873 and 1874 seasons, O’Rourke boarded at the South Boston home of Harry Wright and family. This daily exposure to Wright’s dignified conduct and professionalism would have a lifelong effect on young O’Rourke. Wright also taught Jim, previously a dead pull hitter, how to hit to right field.

10 O’Rourke’s winning heave covered 369 feet on the fly, as reported in the Boston Herald, August 30, 1874.

11 Roer, 43-48. The cricket playing abilities of Harry, George, and Sammy Wright, the sons of an English-born cricket professional, came as no surprise. But apart from O’Rourke and pitching ace A.G. Spalding, the other Americans were pretty much hopeless at the game.

12 Roer, 49-50, citing the Harry Wright Correspondence, Vol. I, 1874-1875, preserved in the Spalding Collection at the New York Public Library. See also William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association, 1871-1875, (Wallingford, Connecticut: Colebrook Press, 1992), 203-204.

13 O’Rourke had not seen a salary increase in three years, playing the 1874 and 1875 seasons for the same $800 stipend that he had received in his first year in Boston. Roer, 62.

14 Soden succeeded N.T. Apollonio as club president. With the assistance of team secretary William Conant and treasurer James Billings – known, with Soden, on the sports pages as the Triumvirs — Soden asserted absolute control over the Boston franchise. He was also a major force in NL executive councils. For more, see Brian McKenna’s excellent BioProject profile of Arthur H. Soden.

15 After a postseason investigation, star Louisville pitcher Jim Devlin and teammates George Hall, Bill Craver, and Al Nichols were permanently expelled from baseball by National League President William Hulbert.

16 Roer, 67-71. Throughout his long playing career, O’Rourke’s uniform would always be kept in immaculate condition, courtesy of the women in his household.

17 John O’Rourke, a left-handed batter and thrower, matched his younger brother’s production, batting .341, with a .521 slugging average and a league-leading 62 RBIs.

18 John would play a few games for the Philadelphia Athletics of the minor-league Eastern Championship Association in 1881 and then sit out the 1882 diamond season entirely. He returned to the majors in 1883, batting .270 for the New York Metropolitans of the American Association. At the close of that season, John retired from baseball, working the rest of his life as a railway baggage handler.

19 As recounted by sportswriter Sam Crane in a profile of O’Rourke published in an unidentified circa 1911 article, preserved in the Jim O’Rourke file at the Giamatti Research Center. O’Rourke did not confine such rhetorical extravagance to his baseball charges, According to his daughter Edith, he also corrected misbehaving O’Rourke children “in five- syllable words.” Lee Allen column, The Sporting News, February 10, 1968.

20 Player discontent with manager O’Rourke was periodically noted in the press. See e.g., Sporting Life, July 16, 1884, and April 22, 1885.

21 For 85 years O’Rourke was deemed the 1884 National League batting titlist. But in 1969 revision of player statistics by the MLB Records Committee conferred the championship on King Kelly (.354). Then in 1999 the MLB reversed course and returned the crown to O’Rourke. But the authoritative baseball-reference.com sticks with Kelly as the batting champ. For more on the controversy, Roer, 114-115, and John Thorn et al., eds., Total Baseball, 7th ed., (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 528-531.

22 Wife Annie O’Rourke ultimately gave birth to eight children: daughters Sarah, the late Anna, Agnes, Ida, Lillian, Irene, and Edith, and son James Stephen, known as Queenie. As the National League did not then play games on Sunday, Jim would only be a train ride away from home most weekends if he signed with a team that played in New York, Providence, or Boston.

23 Technically, the team, as well as the New York Metropolitans of the American Association, was operated by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, the corporate alter ego of Day and junior partners Joseph Gordon, Charles Dillingham, and Walter Appleton.

24 In June 1885 Ward earned a law degree from Columbia University. At about the same time, the New York club, formerly called the Gothams or simply the New-Yorks, acquired the moniker Giants, the name that the team soon made famous.

25 For more on Giants involvement in the players union movement, see James J. Hardy, Jr., The New York Giants Base Ball Club, The Growth of a Team and a Sport, 1870-1900 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1996), 92-94.

26 For one peculiar season, a base on balls was counted as a hit. Elimination of this scoring anomaly reduces O’Rourke’s 1887 batting average to .285.

27 Roer, 124-132. While attending the law school, O’Rourke also coached the Yale baseball team.

28 Genuinely fond of the generous and genial Day, Ward had attempted to avoid injury to the Giants owner by offering him a lucrative position in the Players League executive offices. Ever the National League loyalist, Day refused and waged a stubborn battle against the Players League that ultimately precipitated his financial ruin.

29 Hardy, 143-144; New York Times, September 14, 1892.

30 Washington was one of four American Association teams that survived that league’s demise at the end of the 1891 season. To accommodate Washington and the other new arrivals, the National League expanded to 12 teams in 1892.

31 Adjusted to eliminate the walk/base hit aberration of the 1887 season, O’Rourke’s career numbers are a .310 batting average with 2,639 hits.

32 Roer, 195-199. On occasion thereafter, O’Rourke umpired college games.

33 Roer, op. cit, 201-202. Biographer Roer relates that Jim O’Rourke described himself as a “Theodore Roosevelt Democrat.” But another O’Rourke authority identifies him as a Republican. See Bernard Crowley’s sketch of O’Rourke in Columbia, The Knights of Columbus Magazine, May 1994, 14.

34 As per www.baseball-reference.com. O’Rourke batted .429 in 35 at-bats.

35 Roer, 208. While reflective of O’Rourke’s fair-mindedness, the move was not particularly groundbreaking, as Herbert had played the 1894 season with Pawtucket in the New England League.

36 Connor remained involved in Connecticut minor-league ball for years, playing for the Waterbury team himself until the age of 47.

37 Crowley, Columbia, 14.

38 A career minor leaguer, Queenie O’Rourke appeared in 34 games for the Highlanders in 1908, hitting .231. The origin of his nickname is a mystery but both Mike Roer and Bernie Crowley hypothesize that it may have come from growing up the only male child in a household full of O’Rourke women.

39 For a fuller account of the circumstances, see Benton J. Stark, The Year They Called Off the World Series: A True Story (Garden City, New York: Avery Publishing Group, Inc., 1991), 156-157.

40 For decades, the 54-year-old O’Rourke was considered the oldest player to record a base hit in MLB history. Recent research by SABR members Cliff Blau and Richard Matalzky, however, has transferred the honor to St. Louis Browns coach Charlie O’Leary, 59 years old when he delivered a pinch hit late in the 1934 season.

41 The Sporting News, February 24, 1906. Age and a change in occupational station had also transformed the attitude of former union firebrand John Montgomery Ward. Now a corporate lawyer, Ward had as a client the National League, whose once-hated reserve clause Ward had no compunction about defending in court.

42 New York Herald, January 11, 1910.

43 Bridgeport Evening Post, January 9, 1919.

Full Name

James Henry O'Rourke

Born

September 1, 1850 at Bridgeport, CT (USA)

Died

January 8, 1919 at Bridgeport, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.