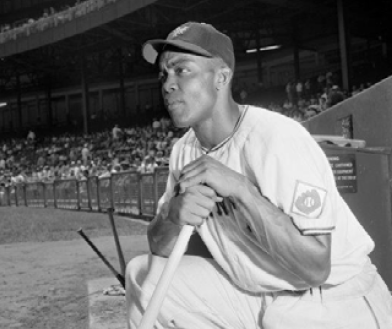

Monte Irvin

Of all those who proudly wore the uniform of the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, Monte Irvin was one of the last surviving players. He went on to a Hall of Fame career as a pioneering African American player in the major leagues.

Of all those who proudly wore the uniform of the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, Monte Irvin was one of the last surviving players. He went on to a Hall of Fame career as a pioneering African American player in the major leagues.

Montford Merrill Irvin was born in Haleburg, Alabama, on February 25, 1919. He was the eighth of 13 children of Cupid Alexander Irvin and Mary Eliza Henderson Irvin. His father, like so many blacks in the American South of the early 20th century, earned a living, if it could be rightly called that, as a sharecropper. Sharecroppers were caught up in an exploitative system of tenant farming where you worked land that you did not own, and had the sale of the crop you raised controlled by the landowner. In such a system there was little opportunity to secure your own land. Besides the economic push that was central to the decision of so many blacks in what historians refer to as the great migration to leave the South for the hope of better times in the North, Irvin described in his autobiography an incident in which the threat of violence that was a constant for blacks in the South of his youth figured into his family’s move to the North.

The Irvin family came north to New Jersey primarily for the better opportunities present there for their children. His mother and father must have been surprised when one of those opportunities turned out to be a baseball career that began in high school, advanced to the Negro Leagues, and led to his being one of the group of black pioneers we credit with the integration of our national pastime. As Monte told his baseball story, it actually began when as a youngster on the way to purchase a saxophone at a local music store, he saw a baseball glove in a sporting goods store window that proved too tempting to resist. And so he ended up playing center field with the Eagles of Newark rather than first sax with all-time favorite Jimmie Lunceford band.

That first baseball glove led to a high-school career that would be the envy of any athlete.

Arguably, Irvin was the finest all-around athlete ever to graduate from a New Jersey high school, earning 16 varsity letters in four sports at Orange High while setting a state record for the javelin throw. His athletic prowess made no difference on senior prom night when he and his date, and a friend and his date, were refused service at a late-night eatery in their hometown because of the color of their skin. The year was 1937.

While Irvin took great pride in his track and field and football accomplishments, he recollected a childhood filled with dreams of playing baseball.

I just wanted to be a real good ball player. I didn’t know if I’d ever play professionally. I didn’t know if I’d ever play in the major leagues. I certainly wanted to play in the Negro Leagues. You see at that time we aspired to play in the Negro Leagues. That was as high as our aspirations could go. I would say, now one of these days I would like to play for the Homestead Grays; I would like to play for the Newark Eagles; I would like to play for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, or the Lincoln Giants. If you were a baseball player you did aspire to play for those clubs. We never knew that later on we would get a chance to play in the majors. But those were our inspirations at that time.1

After a tryout at Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, where he was playing while still in high school with that city’s semipro Smart Set team, Irvin joined the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. He played under the assumed name of Jimmy Nelson to preserve his amateur status, allowing him to continue to play high-school and college ball. He is most remembered from his major-league days as a fine outfielder. But in the Negro Leagues his athleticism translated into a versatility that saw him as a surehanded infielder with a strong throwing arm from third base and shortstop, with quality time in center field as well. During the Eagles’ championship season of 1946, they could boast of a second-base/shortstop combination who would turn out to be Hall of Famers, with Irvin at short combining with teammate Larry Doby at second for strength up the middle.

From 1937 through 1940, Irvin established himself as one of the best in the Negro Leagues. After a strong 1941 season in which he compiled a batting average of .401 in league play, he was refused what he thought was a reasonable salary increase for 1942 from Eagles co-owner Effa Manley. With a salary offer from Mexican baseball magnate Jorge Pasquel well in excess of anything the Eagles were willing to offer, it was an easy decision for Irvin to succumb to the lure of Mexican baseball.

His record with the Vera Cruz Blues was all the more outstanding considering that his move from Newark caused him to miss almost a third of the Mexican season It included a league-leading 20 home runs and a league-leading .397 batting average.

One of those 20 homers was especially interesting. In a game in Mexico City when it was Monte’s time to bat, the Blues owner, Pasquel, called him over to his box seat and in effect ordered him to hit a home run. Monte demurred, saying the best he could do was to keep the rally going. Pasquel insisted that it be a home run. When Roy Campanella, catcher for the Monterrey team, learned from Monte what was going on, he said, “No way.” After taking a strike, and fouling off the second pitch, Monte, guessing fastball, caught one on the fat of the bat for a game-winning shot over the center-field fence. Campanella was beside himself until Monte came over and said that Pasquel had given him $500 and told him to split it with Campy. “My man, my man,” said Campy in reply.2

Irvin referred to his year in Mexico City (1942) as the best year of his life. “For the first time in my life I felt really free. You could go anywhere, go to any theater, do anything, eat in any restaurant, just like anybody else, and it was wonderful. The Negro League owners and players took a poll that year asking which player would be the perfect representative to play in the major leagues. They said I was the one to do it, the perfect representative. I was easy to get along with, and I had some talent.”3

Irvin’s plan to be back in Mexico for the 1943 season was thwarted by the wrong answer from the Newark draft board when he asked for permission to join Vera Cruz for spring training. He expected that a knee injury would have him fail the required physical examination. Besides, he was married with a child. Neither his “football knee” nor his wife, Dee (Dorinda Otey), and daughter, Pamela, worked to secure a deferment for him in this instance.

Irvin was in the Army and away from baseball for three years during World War II. His outfit was the all-African American 1313th General Services Engineers, which served in England and France, where, with no chance to play baseball, he told historian Jim Riley “he built bridges and roads, and did guard duty.”4 Irvin went in as a private and was honorably discharged as a private, having been demoted on his last day from buck sergeant for being an hour late in returning to base.5

Irvin recounted his war experience at some length to Peter Golenbock:

“When I went into the war I was treated very shabbily. I was with a black unit of engineers in England, France and Belgium. More than anything else we weren’t treated well in the army. They wouldn’t let us do this. We couldn’t do that. The guys said, ‘If they weren’t going to give us a chance to perform, to reach our potential, why did they induct us into the army?’”

“All our commanding officers were white. In England we had a southerner who had no business being a company commander. He made some remarks about no fraternization with whites. We couldn’t do this, couldn’t that. After he spoke, we had a company chaplain who got up and said, ‘Men, you are members of the United Sates Armed Forces. You can do anything anybody else can do. I assure this company commander will be gone in two weeks.’ And he was. He was replaced by a lieutenant, a black company commander. This was 1944 in England in a little town called Red Roof in southern England.”

“We felt like we were thrown away. We built a few roads, and when the German prisoners started to come in, we guarded the prisoners. We thought it would have been better if they hadn’t inducted us, and just let us work in a defense plant. We were just in the way.

“I got home on September 1, 1945. In October, I started playing right field for the Newark Eagles. I had been a .400 hitter before the war. I became a .300 hitter after the war. I had lost three prime years. I hadn’t played at all. The war had changed me mentally and physically.”6

The Eagles team Irvin returned to in 1946 was poised to have a great season with a pitching staff led by fellow returning Army veterans Leon Day and Max Manning. The high hopes of team owners Abe and Effa Manley to win the Negro National League pennant were boosted by an opening game no-hitter pitched by Day. Irvin played a major role in the team’s entry into postseason play with a league-leading .404 batting average. A tight seven-game Negro League world series saw him lead the Eagles to victory with three home runs while hitting .462 against the Monarchs of Kansas City whose pitching staff featured future Hall of Famers Hilton Smith and Satchel Paige.

The Eagles’ reign as Negro League champions was the high point for Monte’s black baseball career. That same 1946 season marked the debut in white baseball of Jackie Robinson in the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm club, the Montreal Royals. What followed was a painfully slow process of integration that bled the Negro Leagues of its top players, with fans following their stars into major-league stadiums.

While Robinson was first, if Branch Rickey’s decision had been based purely on baseball ability, Irvin should have been his choice. Who could be better than “faster than lightning” James “Cool Papa” Bell to tell us who in the eyes of Negro Leaguers should have been first? “Most of the black ballplayers thought Monte Irvin should have been the first black in the major leagues. Monte was our best young ballplayer at the time. He could hit that long ball, he had a great arm, he could field, he could run. Yes, he could do everything.”7 This was a judgment shared by most Negro League owners.

If integration had been just a bit slower in coming, and if he hadn’t been so fine a player, all the baseball talent that was Monte Irvin would likely never have been showcased in the big leagues.

When he came up to the majors in 1949, Irvin commented that “this should have happened to me 10 years ago. I’m not even half the ballplayer I was then.”8 His friend Roy Campanella agreed: “Monte was the best all-round player I have ever seen. As great as he was in 1951, he was twice that good 10 years earlier in the Negro Leagues.”9

Irvin told Golenbock, “On July 8, 1949, Hank Thompson and I reported to the New York Giants. Leo Durocher came over and introduced himself. And when everyone got dressed, he had a five-minute meeting. He said, ‘I think these two fellows can help us make some money and win the pennant and the World Series. I am going to say one thing. I don’t care what color you are. If you can play baseball you can play on this club. That’s all I am going to say about color.’ This was two years after Jackie. They had gotten used to seeing an Afro-American on the field. It wasn’t a picnic. We heard the names. But we didn’t have it as rough as he did.”10

It is his 1951 season with the New York Giants that defines Irvin’s greatness as a baseball player. He was coming off his first full year in the majors, in which he had established himself as a solid, promising cog in the Giants’ lineup. At 32 years of age, segregation had cost him his prime. With his .312 batting average, 24 home runs, and 121 runs batted in, he came close to winning the MVP award, finishing third to Roy Campanella and Stan Musial. He scored 94 runs, hit 11 triples, and drew 89 walks while only striking out 44 times, and he went 12-for-14 in steals. In the field, he more than matched his prowess at the plate with his .996 percentage, a product of only one error all season. He was fifth in batting average, fourth in on-base percentage, seventh in slugging, tied for 10th in runs scored, seventh in hits, ninth in total bases, third in triples, tied for 10th in homers, and his league-leading 121 RBIs were 12 better than his nearest competitors. It was an across-the-board outstanding season for what was essentially a rookie campaign for this veteran Negro Leaguer. Irvin finished seventh in walks, tied for eighth in steals, fourth in runs created, fifth in times on base, and tied for third in times hit by a pitch. His outstanding regular-season play more than carried over into the World Series, in which he hit .458, tying a record with his 11 hits. In Game One of the Series, he gave his Giants fans the thrill of a steal of home in the first inning against Yankees ace pitcher Allie Reynolds.

A broken ankle suffered sliding into third base during spring training 1952 limited Irvin’s playing time to 46 games. His absence from the lineup could well have made the difference in a close race with the Dodgers, whose 96-57 gave them the National League pennant over Irvin’s Giants’ 92-62.

The next season, 1953, was a comeback year for Monte Irvin, but decidedly the opposite for his Giants. His .329 batting average with 97 runs batted in could not offset the loss of Willie Mays to Army service, and a pitching staff that had declined considerably from the glory year of 1951. The Giants finished in fifth place, a distant 35 games behind the 105-49 Dodgers.

There was great anticipation in Giants circles as the 1954 season opened with Willie Mays back in the lineup having completed his Army service. That anticipation was more then met when the Giants finished in first place five games better than the Dodgers, and in the World Series bested the heavily favored Cleveland Indians, who were coming off of a record-setting 111-win season.

The toll that time takes on a player’s performance is clearly apparent when one compares Irvin’s 1951 World Series play with his .458 batting average and record-tying 11 hits with his .222 (2-for-9) in the Giants’ startling four-game sweep of the heavily favored Indians.

One more season with the Giants in 1955, when he saw action in only 51 games and finished with a.253 batting average, found him in the offseason selected by the Chicago Cubs in the Rule 5 draft. He ended his eight-year major-league career giving the Cubs a more than respectable 111 games played with a .271 batting average.

After retiring as a player, Monte Irvin worked in public relations with Rheingold Brewery, as an assistant to the commissioner of baseball, and as an outstanding public educator as regards the history of the black leagues in which he starred.

He had two daughters, Patricia Denise Gordon and Pamela Irvin Fields.

With the deaths of his teammates Max Manning and Larry Doby, Irvin became the last of the Eagles who soared to the heights of baseball greatness on the 1946 world champion Newark club that bested the Kansas City Monarchs in one of the best of Negro League fall classics. He was inducted into the baseball halls of fame of Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the United States.

Irvin died on January 11, 2016, at his home in Houston. He was 96 years old.

An updated version of this biography is included in the book “The Newark Eagles Take Flight: The Story of the 1946 Negro League Champions” (SABR, 2019), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin. It also appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Golenbock, Peter, In the Country of Brooklyn (New York: William Morrow, 2008).

Hogan, Lawrence, The Forgotten History of African American Baseball (Santa Barbara: ALC-CLIO, 2014).

Irvin, Monte, with James Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1996).

Riley, James, Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994).

Notes

1 Interview for Before You Can Say Jackie Robinson documentary, copyright 2006, Union County College, Cranford, New Jersey.

2 Monte Irvin with Jim Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1996).

3 Peter Golenbock, In the Country of Brooklyn (New York: William Morrow, 2008), 148.

4 Nice Guys Finish First, 101.

5 Interview with the author on June 30, 2014.

6 Golenbock, 148.

7 Jack Lang, Long Island Press, February 14, 1974.

8 Monte Irvin quote cited in Hogan, The Forgotten History of African American Baseball (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clip Praeger, 2014), 202.

9 Ibid.

10 Golenbock, 150.

Full Name

Montford Merrill Irvin

Born

February 25, 1919 at Haleburg, AL (USA)

Died

January 11, 2016 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.