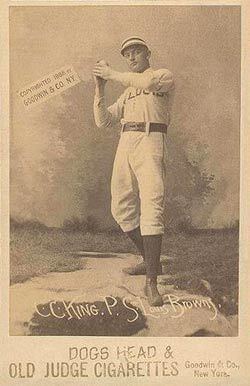

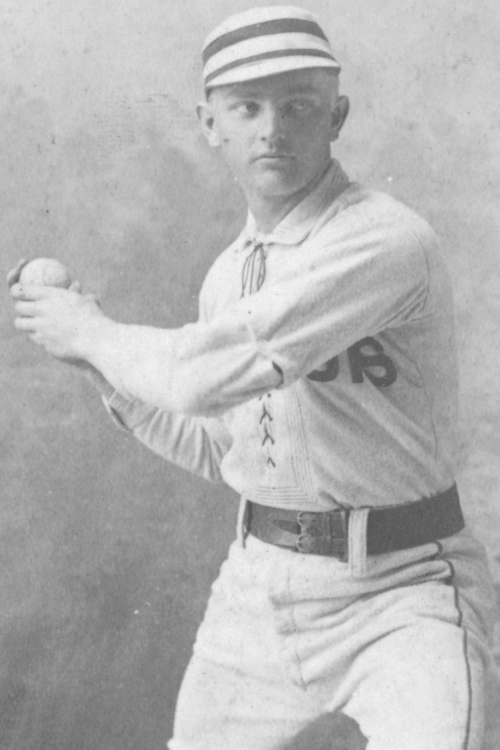

Silver King

Known for his white-blond hair, Silver King emerged as a star in his rookie season, winning 32 games and helping the St. Louis Browns to the 1887 American Association pennant. He recorded at least 30 victories in his first four big-league seasons, including a league-best 45 in 1888, at a time when the pitching distance measured 55½ feet. Fiercely independent, self-confident, unpredictable, and often combative, King notched a 203-152 record in parts of 10 seasons with seven teams.

Known for his white-blond hair, Silver King emerged as a star in his rookie season, winning 32 games and helping the St. Louis Browns to the 1887 American Association pennant. He recorded at least 30 victories in his first four big-league seasons, including a league-best 45 in 1888, at a time when the pitching distance measured 55½ feet. Fiercely independent, self-confident, unpredictable, and often combative, King notched a 203-152 record in parts of 10 seasons with seven teams.

Silver King was the baseball name for Charles Frederick Koenig. King is English for the German word König, transliterated to Koenig. His father, William Koenig, had emigrated with his parents from the Kingdom of Prussia in 1841. They settled in St. Louis, a rapidly growing metropolis on the Mississippi River known for its large settlement of German-speaking immigrants.

William married Dorothy Wahrenburg, whose parents also emigrated from Germany, around 1861. In the first two decades of their marriage, they welcomed eight children into the world, of whom Charley was their third.1 He was born in St. Louis on January 11, 1867 (though some sources show his year of birth as 1868).2

William worked as a bricklayer and later became a “well-to-do contractor.”3 Mother Dorothy tended to the family. The Koenigs resided in their own house on Dekalb Street, in the densely packed Soulard neighborhood, situated just blocks from the city’s bustling wharf and in the shadows of the burgeoning Anheuser-Busch brewery.

King began playing amateur baseball as early as 1884, serving as a pitcher and outfielder for the St. Gothard and Pies Peach clubs in highly competitive St. Louis city leagues.4 The following summer King joined the Jacksonville Blues, a semipro team in Illinois, at the invitation of former Pies Peach teammates Jack O’Connor and Patsy Tebeau.5

In 1886 King’s professional career commenced when he followed O’Connor and Tebeau to St. Joseph, Missouri, about 25 miles north of Kansas City, to play for the Reds in the inaugural season of the six-team Western League. He was signed by manager Nin Alexander, a fixture in the St. Louis area baseball scene, from which about half of his team’s players emerged. During the 80-game season, King emerged as the “crack pitcher” of the circuit, wrote Sporting Life.6 By season’s end King was “eagerly sought” by teams in the National League and American Association, reported the St. Joseph Gazette. Chicago, Philadelphia, and Louisville seemingly had the best shot of signing the hurler.7

On September 26, according to the Gazette, King signed with the Kansas City Cowboys, who had been admitted into the NL on a trial basis in 1886.8 King joined the team in New York City, going 1-3 in five starts in his first taste of big-league ball. He debuted on September 28, tossing a six-hitter but losing to Tim Keefe and the Giants, 3-2. The New York Tribune noted King’s “good work,” but seemed more interested in his appearance and behavior. “He resembles [Jack] Glasscock slightly,” opined the paper, comparing him to the St. Louis Maroons’ light-complexioned infielder, “but acts like a jumping jack when pitching the ball.”9

King was a rugged specimen, 6 feet tall and about 180 pounds. According to sportswriter Edgar G. Brands, King “possessed wide shoulders, a barrel chest, long brawny arms, [and] hands so big that they could completely surround and hide the ball.”10 Notwithstanding his muscular physique, honed from learning the brick trade from his father, King’s most distinguishing characteristic was his “tow-headed” shock of silver hair and light skin tone.11 “[His] complexion is so red and his hair so silvery,” wrote St. Louis sportswriter Joe Pritchard, “that when he steps in the sun, he reminds me of a silverside fish.”12 King had acquired the moniker Silver by 1886, though newspapers regularly referred to him as Charley as well.

The NL replaced the uncompetitive Cowboys (30-91) with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the American Association in 1887. Kansas City’s players were reserved by the NL and subsequently sold by NL President Nicholas Young.13 According to one story, Browns official and sportswriter George Munson went to the office of The Sporting News, in St. Louis, and inquired about the best unsigned and unreserved pitcher.14 Munson subsequently referred King’s name to Chris von der Ahe, the eccentric German-born owner of the St. Louis Browns. “Der Poss Bresident” acquired King, whom one sportswriter hailed as “one of the speediest pitchers in the country.”15 The two-time reigning champion Browns, skippered by 27-year-old Chicagoan Charles Comiskey, were widely favored to capture another title.

Rules governing pitching had evolved steadily since the founding of the first professional league, the National Association, in 1871. Historians Erick Miklich and John Thorn have noted that the NL and AA played by the same pitching rules in 1887.16 The pitcher stood with his back foot on the line of a pitcher’s box 5½ feet long by 4 feet wide. The front of the box was 50 feet from home plate.17 Though all restrictions on pitching delivery had been lifted in 1884-1885, giving rise to overhand hurling, the pitcher still had to hold the ball so the umpire saw it and was permitted only one step to home plate. Perhaps an even greater impact on the game came in the 1887 season — a “major capitulation” to the hitters, argued Thorn.18 For that season only, batters were given four strikes and five balls and walks were counted as hits, causing batting averages to rise dramatically and increase scoring.19

A chance to pitch, let alone succeed, was far from certain for the green recruit King. The Browns’ staff featured two of the Association’s best hurlers: Dave Foutz, who tied for the AA lead with 41 victories in 1886, and Bob Caruthers, whose 30 wins ranked fifth. King made a “favorable debut” on April 26 in the Browns’ 19-6 rout of the Cincinnati Red Stockings at Sportsman’s Park, located on the north side of the Gateway City.20 The Globe-Democrat gushed about his “great speed and curves and [his] command of the ball.” On the other hand, the paper noted that “in batting, his work is somewhat marred by an evident fear of being hit by the ball, as he steps away from the plate when the ball is delivered.”21

The press compared King unfavorably to Foutz and Caruthers, who also formed a tandem in right field on their offdays from pitching. Both were excellent hitters, each batting .357 in 1887. King never developed as a hitter, batting .198 in his career. Also, he rarely played a different position, which limited his value at a time when teams consisted of 12 players, sometimes fewer.

The Browns began the season on a 31-5 roll and coasted to their third straight title, 14 games in front of runner-up Cincinnati. Arguably the best team in the 10-year history of the AA (1882-1891), the Browns established a league record with 95 wins (against 40 losses) and were the first professional team to score at least 1,000 runs. King emerged as a dependable workhorse, finishing in the top 10 in most statistical categories, including fourth with 32 wins (against 12 losses) and ninth with 390 innings pitched. With Caruthers (29-9) and Foutz (25-12), he formed the most effective trio in the league. King’s season featured highlights against the New York Metropolitans. On June 4 he recorded his first shutout, a 1-0 two-hit victory at the St. George Cricket Grounds.22 On August 27 King’s sparkling one-hit, 10-1 victory was “decidedly the best game pitched in the home grounds this year,” cooed the Globe-Democrat.23

For the third straight season, von der Ahe organized a postseason barnstorming championship series with the NL pennant-winner. Known as the Dauvray Cup, it took place immediately after the regular season. He agreed with Fred Stearns, owner of the Detroit Wolverines, to play a 15-game, nine-city series from October 10 to 26. Stearns had put together a super team, acquiring Dan Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, Jack Rowe, and Deacon White in the previous two years. The Wolverines trounced the Browns, winning seven of the first nine games and 10 in total. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch described King as the “poorest of the Browns” pitchers and a “weak hitter and very rank fielder.”24 He started only two of the first 11 games, getting blown out, 8-0, in Game Four at Recreation Park in Pittsburgh and losing Game Nine at the Baseball Grounds in Philadelphia, 4-2.25 The series devolved “into a farce,” according to the Globe-Democrat, with little fan interest for the final four games in St. Louis.26 King won a darkness-shortened six-inning affair in Game 12, 5-1. He lost Game 14, 4-3, despite yielding just one earned run and fanning nine.27

The mercurial von der Ahe didn’t take the humiliating loss to the Wolverines lightly and began dismantling the roster. Most notably, he sold both Caruthers and Foutz to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, who became the favorites to capture the title in 1888. Few expected the Browns to contend, but their players were far from idle in the offseason. By early November the Browns, with a reduced roster, commenced a 2½-month long exhibition tour, most of which was played in San Francisco and the Bay area. The “Frisco Season” featured games between the Browns and the NL Chicago White Stockings, New York Giants, Philadelphia Quakers, all of whom also played local nines, amateur clubs, and minor-league teams.28

King was the “cynosure of all ‘peepers,’” Sporting Life proclaimed as the Browns began their question for a fourth consecutive title with an unproven roster.29 In an omen, the 21-year-old King exhibited “marvelous speed” and “puzzling curves” in shutting out the Louisville Colonels on two hits with no walks in the season opener at Sportsman’s Park.30 As expected, Brooklyn moved into first place early in the season and held a 6½-game lead over the Browns on June 10. Contrary to predictions, the Browns were a resilient squad and went on a 15-2 tear. They moved into first place behind King’s 5-3 victory over the Athletics on July 1.

Nine days later, it appeared as if the club had collapsed after Brooklyn swept a four-game series in St. Louis. King absorbed two of those losses, matched against his former teammate Caruthers. Yet thereafter, Brooklyn stumbled, and the Browns got hot again. They were led by King, whom skipper Comiskey sent to the mound in almost half of the team’s games. Two other youthful hurlers — 19-year-old Nat Hudson (25-10) and 20-year-old Ice Box Chamberlain (11-2) — emerged as strong supporters.

King’s win over the Baltimore Orioles on July 25 moved the Browns back into sole possession of the top spot. They never looked back, extending their lead throughout August, propelled by one of the best stretches of pitching in King’s career. He shut out the Athletics on two hits on August 12, followed by a three-hit shutout against the Cleveland Blues two days later.31 King hammered the last nails in Brooklyn’s coffin by humiliating them twice in the Browns’ three-game sweep at Sportsman’s Park (August 20-22). He tossed yet another two-hit shutout and a curious one-hitter.32 In the latter, the only hit occurred in the ninth inning when outfielders Tip O’Neill and Harry Lyons “stood and looked at each other while the ball dropped.”33

The Browns (92-43) won the pennant, finishing 6½ games over Brooklyn. King laid claim to the title of best pitcher in baseball. He led both the AA and NL with 45 wins (while losing 20); 64 starts, all of which he completed; and 584⅔ innings. He also posted a 1.63 ERA, the lowest in the AA since its inaugural season.34

Von der Ahe agreed to engage John B. Day’s NL champion New York Giants in the Dauvray Cup. He made a disastrous concession, though: playing the first six games of the 10-game series on the East Coast. The Giants (84-47) featured six future Hall of Famers, Roger Connor, Buck Ewing, Jim O’Rourke, and pitchers Mickey Welch, Tim Keefe, and John Montgomery Ward. King was matched up with Keefe (35-12) in Games One, Three, and Five. He lost each by narrow margins (2-1, 4-2, 6-4) in the Polo Grounds, as the Giants took five of the first six contests. King defeated little-used Ed Crane in Game Seven, 7-5, played at Sportsman’s Park. Keefe clinched the Giants’ series win in the next game; the final two games devolved into mockeries, with 50 total runs scored. It was the last time King participated in the postseason. He finished with a misleading 2-6 record (2.18 ERA) in nine starts.

King was credited as one of the first pitchers to use a crossfire delivery.35 According to one description, King began his delivery in the back left corner of the pitcher’s box and stepped to the right, releasing the ball as his hand flew over his shoulder.36 “We didn’t know much about winding up,” said King decades after retiring. “[M]ost of the pitchers threw the ball while standing in an upright position and taking only one step.”37

According to one report, King was slow and deliberate on the mound. “King has a habit of hugging the ball close to his bosom,” read the Pittsburgh Dispatch, “and posing like a man in pain before delivering it.”38 King’s success resulted from this unusual motion coupled with hard throwing. “My pitching stock consisted mainly of speed,” he explained. “I threw some curves, but I never knew about such things as a spitball, a fadeaway, shine ball and all those tricks. You simply had to be a Colossus or you couldn’t stand the gaff.”39

King’s 1889 season was wracked with tension, controversy, inconsistencies, and disappointment. For the second straight spring, he wrangled with von der Ahe over salary, holding out until just about a week before the season started.40 Yet despite the lack of spring preparation, King took the mound on April 17 for the season opener in “base-ball mad” Cincinnati. He defeated the Red Stockings, 4-1.41

King’s 1889 season was wracked with tension, controversy, inconsistencies, and disappointment. For the second straight spring, he wrangled with von der Ahe over salary, holding out until just about a week before the season started.40 Yet despite the lack of spring preparation, King took the mound on April 17 for the season opener in “base-ball mad” Cincinnati. He defeated the Red Stockings, 4-1.41

Three weeks later reports emerged that King’s arm was a “trifle lame.”42 He suffered a horrendous stretch, including yielding 11 earned runs in the final inning of a relief outing on May 5 against the reincarnated Kansas City Cowboys.43 Still, despite King’s troubles and a reported case of malaria, the Browns got off to another hot start.44 They took two of three against the Bridegrooms in Brooklyn from May 30 to June 2, including King’s one-hitter and game-winning RBI single in a 2-1 affair, That extended their lead over their archrivals to five games.45

Fueled by feuding between team-owners von der Ahe and Charley Byrne, the Browns-Brooklyn rivalry took bizarre turns as the summer progressed. After King lost consecutive starts to Brooklyn on July 3 and 4 in St. Louis, von der Ahe charged the pitcher and third baseman Arlie Latham with conspiring with known gamblers and racketeers to throw the games. An astonished King told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that he felt like punching his owner for such slanderous accusations.46 Threatening an investigation, von der Ahe eventually suspended Latham, but not King.

Unsavory charges aside, the Browns still occupied first place on August 28 — but a collapse ensued. They won just three of their next 14 games (also playing to three ties), which turned a three-game lead into a five-game deficit and doomed their season.

That stretch was marred by a violent and contentious series between the archenemies. On September 7, the Browns were leading 4-2 in the sixth inning in front of an estimated 15,000 spectators at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. Skipper Comiskey appealed to umpire Goldsmith to call the game due to darkness.47 When he refused, the Browns resorted to stalling shenanigans. Von der Ahe antagonized Goldsmith by lighting candles on the dugout bench. Spectators pelted the candles with beer glasses, knocking them over and catching a bundle of paper on fire near the grandstand. Other delay tactics ensued, including dropping the baseball into water. Finally, Comiskey pulled his team off the diamond in the ninth inning; consequently, Goldsmith awarded the game to Brooklyn by forfeit. A riot ensued as Browns players were roughed up leaving the ballpark.

For the game on Sunday, September 8, von der Ahe refused to take his squad to Ridgewood Park in Queens (where the Bridegrooms played on Sundays because of Brooklyn’s blue laws). He cited imminent danger and inadequate police protection. As a result, Goldsmith declared another forfeit.48 The third game was rained out, preventing an escalation of violence.

Association President Weldon Wycoff began an investigation. He eventually overruled Goldsmith, declaring the first game a tie, but the damage was done.49 Even though the Browns went on a 13-1 tear (with one tie) to conclude the season, the Bridegrooms were almost as good, going 11-3 (also with one tie). Brooklyn captured the title by two games. King finished runner-up in the league to Caruthers with 35 wins (against 16 losses) while hurling 459 innings.

King married Della Loring around 1890. Together they raised four children: Charles Jr., Helen, Oliver, and Ethel.50 A lifelong St. Louisan, King followed in his father’s footsteps, working as a bricklayer and contractor in the offseason in addition to participating in barnstorming tours and exhibition games.

A month after the 1889 season, King jumped to the Chicago Pirates of the newly established Players’ League. The circuit emerged from the players’ first union, the Brotherhood of Professional Base-Ball players, led by pioneer John Montgomery Ward. As SABR members John Bauer and Gordon Gattie have discussed, the league attracted players dissatisfied with labor relations in Organized Baseball. It promised higher salaries, better working conditions, and team stock options.51 Seven of the league’s eight clubs competed in National League cities. The majority of the players came from NL clubs, but two Association teams, St. Louis and Philadelphia, were especially affected by “contract jumpers.”

The Browns lost five starters to the Chicago Pirates: In addition to King, they were Jack Boyle, Latham, O’Neill, and Comiskey, who became the Pirates skipper. “[G]reat as the Chicago team appears on paper,” gushed the Chicago Tribune, “it appears even greater on the field.”52 As it developed, though, the Pirates finished fourth in the PL standings.

In the franchise opener, on April 19 in Pittsburgh, King tossed a five-hitter to beat Pud Galvin and the Burghers, 10-2, in Exposition Park.53 The Pirates were expected to be an offensive powerhouse. Their outfield had two-time AA batting champ O’Neill and two stars from the NL’s Chicago Colts (later known as the Cubs), Hugh Duffy and Jimmy Ryan. However, the team’s batting was inconsistent and underwhelming. It struggled to pay .500 ball for the first third of the season, falling to 23-23 on June 21 when King tossed an eight-inning no-hitter at Chicago’s South Side Park against Brooklyn, yet lost 1-0.54 Brooklyn tallied its run on an error and didn’t bat in the ninth after losing the coin toss to determine who would bat first.

The Pirates began a winning streak the next day, punctuated by King’s June 27 victory over one of his heroes: the measuring stick of durability, Old Hoss Radbourn, then with the Boston Reds. King threw a four-hitter and won, 2-0.55

Again throwing a four-hitter, King beat the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders, 8-2, in Eastern Park on July 8. That gave the Pirates their 14th win in their last 16 games and transformed an eight-game deficit into a half-game lead in the standings.56 But the team slumped thereafter, losing 13 of 20. Chicago never mounted another challenge, finishing at 75-62, ten games behind the Reds. Mark Baldwin (33-24) and King (30-22) proved to be the bright spots on the club. Both started a league-high 56 times and they finished 1-2 in victories, innings (492, 461), and complete games (53, 48). King paced the circuit with a 2.69 ERA and four shutouts.

The Players’ League collapsed and officially folded after one season. It appeared that King would return to the Browns, who apparently owned his reserve rights; however, his status was unclear. In early March King’s former teammate Mark Baldwin, who had signed with the NL’s Pittsburgh Pirates, was arrested in St. Louis. He was charged with tampering with King’s contract in an attempt to persuade him to sign with Pittsburgh.57 King’s enmity for von der Ahe was well known. As a Brown, he bristled at the self-promoting owner’s constant meddling in on-field issues. Indeed, King was known for his impatient and highly competitive — some claimed disagreeable — temperament. Nonetheless, von der Ahe was surprised by his hurler’s refusal to report to the club on April 1, giving rise to more speculation about King’s future.58

On April 4 Baldwin was released from his charge of conspiracy, only to be arrested in St. Louis on the same charge. Baldwin once again posted bail, but the grandstanding von der Ahe claimed to have “proof positive” that King would play for the Pirates.”59 After King was not in uniform for the Browns for their opener on April 8, Pittsburgh papers reported regularly in the next days that he was expected in the Steel City any day.

The drama intensified when King was not with the Pirates for their season opener on April 22, giving rise to yet more rumors that he might sign with Cincinnati.60 Finally, on April 27 baseball fans in Pittsburgh read the headline “The King Is Here.”61 King signed for $5,000, the largest contract of his career, and officially joined the club.

Pittsburgh was coming off one of the worst seasons in major-league history (23-113), but expectations were high with the addition of Baldwin and King. The latter (by then aged 24) debuted on April 30, tossing four innings and knocking in the deciding run in Pittsburgh’s 4-3 victory over the Cleveland Spiders.62

Yet the transition to the NL was anything but smooth for King. Pittsburgh papers reported about his “sound thumping[s]” throughout May and June, and rumors churned that he might even be released.63 “The white-headed German had as much speed as an old woman throwing corn to the chickens,” read an especially acerbic remark.64

King did round into shape, flashing the form that made him one of the best pitchers in baseball, For example, he tossed a one-hitter and a three-hit shutout in consecutive starts on June 30 and July 2.65 But the cantankerous King scrapped with his skipper, Ned Hanlon, and openly charged his teammates with loafing when he was on the mound. All of this led to a toxic situation and contributed to another last-place finish for the Pirates.66

By that time, however, King was no longer with the team. Club owner Palmer O’Neill released the disgruntled hurler on September 23 for failure to take a pay cut and sign his contract for the 1892 season.67 King led the NL with 29 losses and won just 14 times, but did finish in the top 10 in starts, compete games, and innings pitched.

King signed with the New York Giants, managed by Pat Powers. A series of bizarre events defined his tenure with that club. The first controversy occurred in his debut on April 20, in Baltimore. The Giants were losing 6-5 after six innings when the Orioles suddenly left the field to catch a train scheduled to depart less than an hour later.68 Umpire Jerry Mahoney declared the game a forfeit and awarded the victory to the Giants because manager George Van Haltren had failed to notify all parties prior to the game about the travel situation.

King’s surly, confrontational, and increasingly erratic behavior alienated teammates. Just weeks into the season, Sporting Life opined, “King is already beginning the tactics which got him into trouble and disfavor with every club he has played for.”69

That wasn’t all. In mid-May, King and teammate Jack Boyle made sports headlines across the country for their “unsavory mess.”70 While in Cincinnati on a road trip, they met two women and subsequently brought them back to a New York hotel under the guise that the couples were married. The incident raised fears that the players might face prosecution for immoral behavior — which they were not.

July 5 marked a turning point for King and his career. After suffering a loss to the Colonels, the team’s 14th in its last 18 games, he left the club without warning. “King is just as thick-headed and sulky with New York as he was with the Chicago and Pittsburgh clubs,” wrote Sporting Life.71 While King’s whereabouts were unknown, the newspaper opined that “no one should be surprised” by the player’s mysterious absence, and suggested that he “had no friends on the club” after two other malcontents, George Gore and Charley Bassett, were jettisoned weeks earlier.72

In a financial dispute with the club, King had apparently agreed to a $750 salary reduction before going AWOL, but his dissatisfaction was probably more than just monetary. He claimed that he would be “satisfied” if rumors of his supposed trade to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Tony Mullane were true.73

King finally returned to the team after a three-week hiatus. He made his first appearance on August 5 in relief; three days later came his first start in almost five weeks.74 In what proved to be his last full season in the majors, King (22-24) pitched inconsistently, but was still remarkably durable. He finished in the top 10 in starts (47), complete games (45), and innings (410⅓) despite quitting for a month. In an era of rubber-armed hurlers, the Giants staff in 1892 was especially noteworthy. The trio of King, Amos Rusie, and Ed Crane started all but one of the club’s games and pitched every inning but seven the entire season. Yet the Giants finished in eighth place (71-80) in the 12-team league.

King was back with the Giants in 1893, but a major pitching rule change dramatically reduced his efficacy. As Thorn and Miklich explained, a pitcher’s plate (12 by 4 inches) replaced the pitcher’s box, and the pitching distance was increased to the now-familiar 60 feet 6 inches.75 King struggled adapting to the new distance, as did many other pitchers. The Sun reported that King still had “great speed” — “but every ball he put over the plate was ‘killed.’”76 After yielding 58 runs (47 earned) in 49 innings, King was released in late May. He signed with the Cincinnati Reds, but was unable to rekindle his old magic in his 15 starts (4.89 ERA). After the season, the Cincinnati Enquirer issued a scathing opinion: “He gave the club a good long run of the ‘old con’ game.”77

With the demise of the Players’ League after the 1890 season and the American Association after the 1891 campaign, NL owners were emboldened to reduce salaries and expenses. King fought against this. His demand for fair pay contributed to his portrayal in sports pages as hardheaded and combative, with references that “he didn’t like it here.”78 Unlike many players, King had legitimate earning potential as a contractor in St. Louis, and that independence fueled his attitude. The Reds offered him a salary reported at $1,500 for 1894 — a decrease of 70 percent from what he earned in 1891. Instead, he walked away from the game.

King unexpectedly returned to baseball in 1896, encouraged by fellow St. Louisan Scrappy Bill Joyce, captain of the Washington Senators. The 29-year-old joined the team in mid-May and made his debut in relief on May 24.79 He then tossed a six-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates in his first start five days later.80 Newspapers in Washington gushed about King’s rejuvenation and “sprightly” pitching, as the right-hander won his first four starts.81

However, King’s renaissance came to a crashing end on July 21 against the Cleveland Spiders when Harry Blake’s liner struck and broke his pitching arm.82 Not yet completely healed, King returned to the mound five weeks later, but struggled. Overall, though, he was still one of the few relatively bright spots on a bad team. He finished with a 10-7 record and 4.09 ERA in 145⅓ innings, while the Senators (58-73) posted their sixth of nine straight losing seasons in their nine-year existence.

King was back with the Senators in 1897 despite widespread speculation that he would remain in St. Louis — and even though his friend Bill Joyce had been traded the prior August. King was the third pitching option behind youngsters Win Mercer and Doc McJames. However, he was unable to revive his fastball and the excitement from the previous campaign. In mid-August King (6-9, 4.79 ERA in 154 innings) was released.83 There was some speculation that he would sign with Baltimore, but King hung up his baseball shoes for the last time. In parts of 10 seasons, he won 203 and lost 152, completing 328 of 370 starts among his 397 appearances. He had a 3.18 ERA in 3,180⅔ innings.

King seemed to have worn out his welcome with the Senators, as he had with every other team he had played for. In a critical editorial that September, the Washington Times wrote:

“The strange case of Silver King almost baffles belief. Silver never entered baseball for the love of the sport or through any sentimental ties, but purely for the revenue derived by his cunning wing and his crossfire curves. Even in the days of the champion St. Louis Browns, when Silver was in his prime and flower, there was no professional pride about him, and he seldom seemed to care a straw whether his team won or lost.”84

No one ever doubted King’s ability, but his commitment to his teams seemed to be a different matter. The editorial also reveals an emerging view of baseball players that is still pervasive in the twenty-first century. Namely, fans assume — and perhaps demand — that players should perform altruistically, subjugating personal financial desires and needs for the good of the team and the fan experience.

The lifelong St. Louisan remained successful in his contracting business. He and his family lived in a handsome red brick house at 2907 Magnolia Avenue in the well-to-do Tower Grove neighborhood, about a mile northwest of where he’d grown up.85 After retiring from professional ball, King drifted away from the game. He claimed that he never attended another major-league game once he stopped playing.86

Charles Koenig a.k.a. Silver King retired comfortably at the age of 57. He died 14 years later, on May 19, 1938. He was at Lutheran Hospital in St. Louis, following surgery for gallstones and appendicitis.87 Services were held at the Wacker-Helderle Chapel and he was buried at the family’s large plot in the New St. Marcus Cemetery.88

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 According to the 1900 US Census, the couple had eight children, at which time six were still living. Dorothy’s maiden name is verified by her obituary: “Deaths,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 17, 1919: 18. His older siblings were Willie and Henry; his five younger ones were Sophia, Emma, Louis, Blanche, and Dorothy. Names were determined from the US Census of 1870, 1880, 1890 and 1900.

2 According to his Sporting News player contract card, King was born in 1867. His tombstone also gives the date as 1867. Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org both give his year of birth as 1868.

3 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, August 24, 1887: 5.

4 “King Signs with Browns,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 18, 1887: 8; King’s Sporting News player contract card; “King, Charles, Frederick,” in David Nemec, ed., Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1. The Players Who Built the Game (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 2011), 106.

5 “Silver King and the 1888 Browns He Pitched to Championship,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1918: 10. See also, Greg Olsen, “The Way We Were: Baseball Has a Storied Past in Jacksonville,” Jacksonville (Illinois) Carrier-Journal, April 3, 2017. myjournalcourier.com/news/article/The-way-we-were-Baseball-has-a-storied-past-in-12582807.php.

6 “From Cowboy Town,” Sporting Life, October 6, 1886: 4.

7 “Pitcher King,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, September 26, 1886: 1.

8 “Pitcher King.”

9 “Hard Work to Beat the Cowboys,” New York Tribune, September 29, 1886: 8.

10 Edgar G. Brands, “Silver King, St. Louis Hurling Ace of the 80’s, Dies,” The Sporting News, May 26: 1938: 14.

11 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 25, 1887: 25.

12 Joe Pritchard, “From St. Louis,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1887: 5.

13 Joe Pritchard, “From St. Louis,” Sporting Life, April 27, 1887: 10.

14 Nemec, 106; Brands.

15 Nemec, 106; Brands.

16 John Thorn, “Pitching: Evolution and Revolution,” Our Game, August 6, 2014, ourgame.mlblogs.com/pitching-evolution-and-revolution-efd3a5ebaa83; Eric Miklich, “The Pitcher’s Area,” 19cBaseball, 19cbaseball.com/field-8.html.

17 The pitcher’s box was reduced from 7 feet long by 4 feet wide to 5½ feet long by 4 feet wide in 1887.

18 Thorn.

19 From 1886 to 1887, the AA saw increases in team scoring per game (5.7 runs to 6.6), batting average (.243 to .273), and slugging percentage (.323 to .367); the NL saw averages increases in scoring (5.2 runs to 6.1), batting average (.251 to .269), and slugging (.342 to .381). The most pronounced effect was the drastic decrease in strikeouts. The AA went from 4,730 to 3,075, a drop of 35 percent); and the NL dropped 34.3 percent (4,321 to 2,840).

20 “Base Ball,” Sporting Life, May 4, 1887: 4.

21 “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1887: 5.

22 “Base-Ball and Athletics,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 5, 1887: 9.

23 “Base-Ball and Athletics,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 28, 1887: 9.

24 “Browns Willing,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 1, 1988: 6.

25 “Shut Out,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 14, 1887: 8; “Still Out of Luck,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 20, 1887: 8.

26 “Sporting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 31, 1887: 8.

27 “Gossip of the Games,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 23, 1887: 11; ‘The Same Old Story,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 26, 1887: 8.

28 “Frisco Season,” Sporting Life, December 21, 1887: 21.

29 Joe Pritchard, “St. Louis Siftings,” Sporting Life, April 18, 1888: 3.

30 “The Association Season,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 19, 1888: 8.

31 “Browns, 2; Athletics, 0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 13, 1888: 8; “Browns, 5; Cleveland, 0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 15, 1888: 9.

32 Browns, 1; Brooklyn, 0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 21, 1888: 8; “Browns; 4; Brooklyn, 2,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, August23, 1888: 8.

33 “Browns; 4; Brooklyn, 2,” St. Louis Globe Democrat, August 23, 1888: 8.

34 Will White posted a 1.54 ERA during the inaugural 1882 season.

35 Brands.

36 Robert L. Tiemann, “Charles Frederick King (Silver),” 72. Document from the player’s Hall of Fame file.

37 “Silver King and the 1888 Browns He Pitched to Championship,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1918: 10.

38 “Thumped our King,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, May 7, 1891: 7.

39 “Silver King and the 1888 Browns He Pitched to Championship.”

40 King earned $3,200 in in 1888 and wanted a raise to $3,800 in 1889, eventually compromising with Von der Ahe and signing a contact on April 10. “Charley King, Too,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 11, 1889: 3.

41 St. Louis, 5; Cincinnatis 1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 18, 1889: 5.

42 Joe Pritchard, “St. Louis Siftings,” Sporting Life, May 8, 1889: 3.

43 “Baseball,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 6, 1989: 6.

44 Joe Pritchard, “St. Louis Siftings,” Sporting Life, May 8, 1889: 3.

45 The Brooklyn Times wrote astonishingly that the Browns’ win was the result of King’s “sudden and springing development as a batter.” See “They Got It in the Neck,” Brooklyn Times, June 3, 1889: 3.

46 Under a Cloud,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 17, 1889: 3.

47 Information about the game is from the following: “Forfeited by the Browns,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 8, 1889: 11; “Base-Ball,” Sporting Life, September 8, 1889: 3.

48 “Browns-Brooklyns,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 9, 1889: 9.

49 “The Brooklyn-St. Louis Rowe,” Sporting Life, September 18, 1889: 4. “The Rowe of the Season,” Sporting Life, September 18, 1889: 5.

50 According to the obituary for Silver King, his wife’s maiden name was Loring; see “Death,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 22, 1938: 2F. In obituaries for some family members, the name was spelled Lohring; for example in Charles Jr.’s obituary: “Deaths,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 9, 1935: 6D. Charles Jr. was born in 1885, the three other children between approximately 1897 and 1903. It is possible that Charles Jr., born five years before Silver and Della married, was not their son, even though his obituary claims he was and he is buried in the family plot in St. Louis. In King’s first season with the Browns, in 1887, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported about a scandal involving King and a woman, identified as Emma Goldenloge, who charged him with seduction and threatened to have him prosecuted. According to the report, the two had lived together in St. Joseph and had a son together. See “An Error for King,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 26, 1887: 4. Sporting Life reported that the wealthy Chris von der Ahe, no stranger to scandals himself, stepped into to quiet the matter (“temporarily adjusted”), suggesting a payoff. See “St. Louis News,” Sporting Life, June 1, 1887: 4.

51 John Bauer, “April 19, 1900: Debut of the Players’ League,” SABR Games Project. sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-19-1890-debut-players-league. Gordon Gattie, “The Legacy of the Players’ League, The National Pastime (2015), sabr.org/research/legacy-players-league-1890-chicago-pirates.

52 ‘Won as They Pleased,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1890: 2.

53 “Players Seem Popular,” Chicago Inter Ocean, April 20, 1890: 1

54 “Darling’s Yellow Error,” Chicago Inter Ocean, June 22, 1890: 3.

55 “Players. Chicago 2, Boston, 0,” Chicago Inter Ocean, June 28, 1890: 2.

56 “Chicago Men in the Lead,” Chicago Inter Ocean, July 9, 1890: 2.

57 “Baldwin in Jail,” Pittsburgh Post, March 6, 1889: 6.

58 “Capt. Comiskey Takes Charge,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 2, 1891: 2.

59 “Baldwin Arrested Again,” Pittsburgh Press, April 5, 1891: 6.

60 “Late Sporting News,” Pittsburgh Press, April 23, 1891: 6.

61 ‘The King Is Here,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 27, 1891: 7.

62 “Quite Good Enough,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, May 1, 1891: 6.

63 “Couldn’t Hit Clarkson,” Pittsburgh Post, May 28, 1891: 6.

64 “He Was Walloped,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 27, 1891: 6.

65 “Silver King in His Glory,” Pittsburgh Post, July 1, 1891: 6; “Grand, Magnificent Ball-Playing,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 3, 1891: 2.

66 The National Game,” Pittsburgh Press, July 15, 1891: 5.

67 “Silver King Released,” Pittsburgh Post, September 24, 1891: 6.

68 “New York Get the Game,” (New York) Sun, April 21, 1892: 4.

69 “Editorial Views, News, Comment,” Sporting Life, April 30, 1892: 4.

70 “‘Giants’ Mashes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1892: 2.

71 “Duty of the Hour,” Sporting Life, July 9, 1892: 2.

72 “New York News,” Sporting Life, July 23, 1892: 4.

73 “Coming to His Senses,” Sporting Life, July 23, 1892: 1.

74 “New York Drops a Peg,” (New York) Sun, August 8, 1892: 4.

75 Thorn and Miklich. The modifications had a dramatic effect on the game. Scoring increased from 10.2 to 13.2 runs per game; batting average rocketed from .245 to .280; the number of .300 hitters ballooned from 8 to 30. As for pitchers, total strikeouts decreased dramatically (from 5,978 to 3,342), though walks actually fell by 0.5 percent.

76 “Dissatisfied Ball Players, (New York) Sun, June 18, 1893: 7.

77 “At Once Work Will Be Started,” Cincinnati Enquirer,” December 24, 1893: 10.

78 “Dissatisfied Ball Players, (New York) Sun, June 18, 1893: 7.

79 “Algie M’Bride’s Drive,” Washington Times, May 25, 1896: 3.

80 “‘Silver’ King in Form,” Washington Times, May 30, 1896: 3.

81 “Base Ball Notes,” (Washington) Evening Star, May 28, 1896: 10; “Browns Were Very Easy,” Washington Times, June 13, 1896: 3.

82 “Shut Out in Two Games,” Washington Times, July 22, 1896: 3.

83 “Grounds Were Too Wet,” Washington Times, August 24, 1897:6.

84 “Diamond Dust,” Washington Times, September 17, 1897: 6.

85 The King family address is verified by US census reports and obituaries.

86 Brands.

87 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 216.

88 “Deaths,” St. Louis Star-Times, May 21, 1938: 13.

Full Name

Charles Frederick King

Born

January 11, 1867 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

May 21, 1938 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.