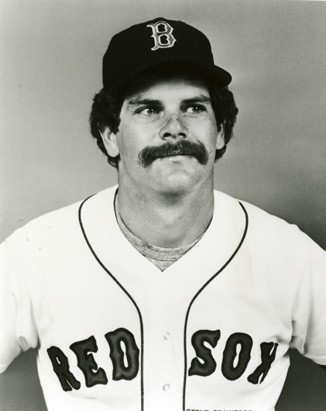

Steve Crawford

Steve Crawford was a pitcher who spent most of his 10 major-league seasons fighting for a job on a major-league roster, the majority of them with the Boston Red Sox. He was a once-promising prospect, but became almost a forgotten man by 1986. He would have been left off the Red Sox’ postseason roster that year had fate not intervened twice. Crawford went on to make a significant contribution to the Red Sox’ postseason run and earned a victory in one of the most exciting games in baseball history with the Red Sox season hanging in the balance; he was credited with the win in one of the most highly anticipated pitching matchups in World Series history.

Steve Crawford was a pitcher who spent most of his 10 major-league seasons fighting for a job on a major-league roster, the majority of them with the Boston Red Sox. He was a once-promising prospect, but became almost a forgotten man by 1986. He would have been left off the Red Sox’ postseason roster that year had fate not intervened twice. Crawford went on to make a significant contribution to the Red Sox’ postseason run and earned a victory in one of the most exciting games in baseball history with the Red Sox season hanging in the balance; he was credited with the win in one of the most highly anticipated pitching matchups in World Series history.

Steven Ray Crawford was born on April 29, 1958, in Pryor Oklahoma, the youngest of six children (three boys and three girls) of Lorraine (Emme) and Opie Crawford. Opie served in the Army during World War II in the Philippines. He was an undefeated boxer until he was wounded when caught in a bomb explosion that left his right side partially paralyzed. After the war, he was a Pentecostal preacher for 35 years and a pulpwood cutter. Lorraine, originally from Nebraska, ran the family farm, which included 300 to 400 head of cattle. Crawford remembered hauling a lot of hay in his younger days.

Crawford’s father was an early influence. “My father was my number one influence. He was my first coach at the age of 5. He taught me how to approach and play the game,” he told the author.1 Early in his career he told a sportswriter, “I’ve been fortunate that I’ve had excellent help my entire life. My father was the biggest help early. He was a three-sport star in high school and used to help me throwing baseballs every day.”2

Crawford was a three-sport high-school star in Salina, Oklahoma. After high school he had full-scholarship offers in three sports, with baseball being his third sport. He played fullback and defensive end on the football team. His older brothers talked him out of football and convinced him that he had a better chance to make it as a baseball player. Crawford was a pitcher-first baseman for Claremore Junior College (now called Rogers State University) from 1977-1978. Crawford drew interest from most of the major-league clubs as they believe he had first-round talent.

On May 6, 1978, the 20-year old Crawford chose to sign as an amateur free agent for less money with the Boston Red Sox by scout Danny Doyle. “Carl Yastrzemski was my idol,” Crawford said. “He always was. I used a Yaz bat. I signed with the Red Sox because Carl Yastrzemski was with the Red Sox. That was one of my reasons, and to play with Carl Yastrzemski, right over there. You never think it could happen. Now you’re talking with him, talking pretty good.”3 Crawford didn’t even know who Yastrzemski was but he liked his bat, then he found out what a great player he was. “The first day I walked into Fenway Park, I was in total awe seeing Carl Yastrzemski and Fenway, a day I will never forget.”4 The Red Sox felt that signing Crawford partially made up for losing three draft picks that year by signing Mike Torrez, Jack Brohamer, and Dick Drago as free agents.

Crawford started his professional career with Winston-Salem in the Class-A Carolina League. He pitched in 19 games, started 14, and sported a 9-5 record with a 3.44 ERA. One of his teammates, Michael Moore, called Crawford “Shag” because of his bushy long hair and mustache, and the nickname stuck.5 The next season, still at Winston-Salem, he started 28 games, compiled an 11-11 record, improved his ERA to 2.94, and walked only 67 batters in 211 innings.

In 1980 Crawford was promoted to the Bristol Red Sox of the Double-A Eastern League. He impressed with a 2.64 ERA in 177 innings and gave up only six home runs. Called up to the Red Sox in September, Crawford made his major-league debut on September 2 at Fenway Park against the California Angels with the Red Sox leading 10-2 in the eighth inning. Crawford pitched a perfect eighth and got out of a two-on, one-out jam in the ninth without surrendering a run, preserving the victory. On September 13 at Fenway Park he relieved Mike Torrez after Torrez gave up four runs to the New York Yankees in the fourth inning. Crawford pitched 4⅔ shutout innings in the 4-3 loss. The next day manager Don Zimmer announced that Crawford would replace Torrez (14 losses) in the starting rotation. With the Red Sox 13½ games out of first place, Zimmer, who was on the hot seat, said, “If I’m still the manager next year, I would like to know if the kid is capable of pitching in the big leagues before we get to spring training.”6

Crawford pitched a complete-game 8-3 victory against the Cleveland Indians on September 18, winning manager Zimmer’s praises again. Crawford said of his performance, “I proved to myself that I could pitch up here. I wasn’t nervous at the start, but I did load the bases [in the first inning]. Then I got the double-play ball and I said to myself that I’m going to be all right.”7 He started four more times, earning a complete-game victory over Toronto, to go 2-0 with a 3.62 ERA. Crawford was one of the few bright spots the Red Sox had in September 1980. Zimmer was fired in the last week of the season.

During spring training in 1981 (Ralph Houk was the new manager), expectations were high for Crawford and he was rated ahead of top pitching prospects Bruce Hurst and Bobby Ojeda by the Red Sox. Crawford on his 1980 season, “I know all of this is in the past, and I will have to go out and prove myself all over again.”8 The 6-foot-5, 225-pound, 22-year-old Crawford, although not overpowering, possessed a 94-mile-per-hour fastball and a good break on his curve. Mild-mannered, he was termed too polite to be called “nasty.”9 Baltimore super-scout Jim Russo called him “one of the three best young pitchers in Florida,”10 and Red Sox minor-league pitching coach Bill Slack said, “He has four good pitches and command of all of them. Not only does he have an idea how to pitch, but he does the little things that help you become a better pitcher.”11 Crawford made the Red Sox rotation.

On April 13, dueling Baltimore’s Jim Palmer, Crawford lost 5-1 but didn’t give up an earned run and four of the Orioles’ runs tallied after he left the game. Red Sox pitching coach Lee Stange praised his fastball, saying “It really moved.”12

Crawford’s season and career took a downturn from this point. He started 10 more games, was 0-5, and his ERA rose to 4.96. Before starting against Oakland in June 6, he shaved his distinctive mustache in an effort to change his luck. “I did it in the minors when things were going bad and I won three in a row after that,”13 No such luck in the majors: Crawford lasted only two inning in a 6-2 loss to Oakland and lost his spot in the starting rotation. The Red Sox planned to send him to Triple-A Pawtucket and call up Bobby Ojeda. But a players strike loomed, and the Red Sox decided not to call up Ojeda before the June 11 strike deadline and risk having him not pitch. Crawford stayed on the major-league roster and was inactive until play resume on August 10. The rest of the season, Crawford had one start and three relief appearances in mop-up roles.

The Red Sox were still high on Crawford, despite his 0-5 record, and hoped for a rebound in 1982. “There is no question he has a big league arm,” Ralph Houk said.14 Unfortunately for Crawford, he developed bone chips in his elbow from throwing the slider in winter ball. “I changed from being a fast ball pitcher to a breaking ball pitcher and that’s how I hurt my arm,” said Crawford.15 The Red Sox team physician, Dr. Arthur Pappas, performed surgery and the timetable was for Crawford to be throwing by the end of spring training and be back on the field by the All-Star break.

When Crawford regained his health, he was on a rehabilitation program and started the 1982 season in Pawtucket. He started 10 games and compiled a 1-4 record with a 4.11 ERA, striking out only 21 batters in 46 innings. Crawford was called up in September and fared better in the majors. He pitched in five games in relief, winning one game with a 2.00 ERA.

Crawford came to spring training in 1983 fighting for a job on the Boston roster. He was on a strict diet and had lost 15 pounds to get back to his 1980 playing weight of 225 pounds. “The one goal I have right now,” he said, “is to be on the plane to Boston. I’ve got a pretty good chance of making the club. But I’ve got to come in and show what I can do. That’s what the Red Sox want to know, to see if my elbow is OK.”16

Crawford didn’t make the cut and spent the entire 1983 season in Pawtucket. He started 27 games, compiling a record of 8-11 with a 5.18 ERA striking out 104 batters in 154⅔ innings. Crawford was disappointed at not making the major-league roster and by his own admission went to Pawtucket with a bad attitude. “The only reason I wasn’t called up last season was me. But I learned a lesson,” he said.17

Crawford entered 1984 spring training again fighting for a job with the Red Sox. The starting rotation looked set with Oil Can Boyd, Bobby Ojeda, Bruce Hurst, and Mike Brown, with the rookie Roger Clemens impressing everyone. Crawford did not make the cut and started the season in Pawtucket. He moved to the bullpen to get another shot at the big leagues, and was recalled on May 9. “Bob Stanley says I’m doing what he did coming back and changing lanes,” said Crawford. “I’m a reliever now and I have to like it a lot. It got me back to the big leagues and that’s where I wanted to be.”18 The important thing,” Houk said, “is that he wanted to do it.”19 During the rest of the season he pitched in 35 games (62 innings) and posted a 5-0 record with a 3.34 ERA.

Still, Crawford was deemed expendable by the Red Sox. In the offseason they attempted to trade him to open up a spot in the bullpen for a left-handed reliever. General manager Lou Gorman had a deal in place at the winter meetings, but it fell through. Crawford said, “I got the feeling I wasn’t wanted despite what I had done and went to spring training to win a job and show some people I could pitch.”20 This time he would have to impress new manager John McNamara. Crawford was impressive in spring training, pitching 11 shutout innings at the start and had this to say about his situation, “I’m happy about my spring thus far, but I’m not taking anything for granted.”21

One difference this season – the once-promising prospect, now 27 years old, knew his role would be middle reliever. “I know what my role is,” he said. “I’m a reliever, not a starter. I can work on growing in that role – going out every other day to get my arm used to that kind of pitching.”22

Relief pitching, said Crawford, was something that suited him. “I can pitch 4-5 innings,” he said, “and it doesn’t bother my arm. I can bounce back in a couple of days. I’d survive for a little while as a short reliever. But the better job, and the place where I’ll make my money, is as a long and a middle man.”23

Using a newly developed four-seam fastball, Crawford was used as a long reliever and spot starter for the first three months of the 1985 season. When closer Bob Stanley needed surgery on his index finger, McNamara turned to Crawford, who responded by leading the club in saves with 12. He also posted a 6-5 record with a 3.76 ERA, pitching in 44 games despite two trips to the disabled list.

There was even speculation that Crawford could be in the mix as Boston’s closer in 1986. Pitching coach Bill Fischer said, “I think he could develop into a fine short man. He’s big, mean-looking on the mound, and can throw hard. Once he starts believing in himself, he’s going to be good.”24

But the Red Sox bullpen was thin and had only 29 saves in 49 opportunities. To shore up the bullpen, the Red Sox traded struggling left-handed starter Bobby Ojeda to the Mets for Wes Gardner and Calvin Schiraldi.25 McNamara wanted another short reliever so he could move Crawford back to his long-reliever/spot-starter role. The Red Sox then traded utility infielder Jackie Gutierrez and acquired veteran long reliever Sammy Stewart from the Baltimore Orioles. During the regular season, Crawford went 0-2 with a 3.92 ERA. In July he went on the DL with a shoulder injury and then spent 20 days in Pawtucket on a rehab assignment. The Red Sox called up Schiraldi to take Crawford’s spot on the roster and Schiraldi would eventually emerge as the closer. Crawford made it back to Boston in September and pitched in 10 games.

The Red Sox made the postseason for the first time since 1975 and faced the California Angels in the American League Championship Series. Crawford would have been left off the postseason roster, but a knee injury to Tom Seaver opened up a spot for him.

The Angels took a commanding three-games-to-one lead and were winning Game Five in the top of the ninth inning, 5-2, when Boston staged a dramatic comeback and scored four runs, capped off by Dave Henderson’s two-run home run. In the bottom of the ninth inning, the Angels battled back to tie the score against Bob Stanley and Joe Sambito. Left-hander Sambito gave up a run scoring single to Rob Wilfong, and Crawford was called in to pitch to Dick Schofield. Sammy Stewart was unavailable as he was hit by a line drive during batting practice the day prior. There was one out and Wilfong, with better than average speed, on first base. With the count 2-and-1, Schofield swung at a fastball tailing in on him and hit a sharp groundball past the diving first baseman, Dave Stapleton. Wilfong advanced to third base. Brian Downing was intentionally walked to load the bases.

The next batter was Doug DeCinces with the potential ALCS winning run 90 feet away. The infield and the outfield were both playing in. DeCinces was 4-for-9 lifetime against Crawford. DeCinces swung at the first pitch and hit a popup to shallow right field, not deep enough for Wilfong to try to score. The infield and outfielders went back to normal depth.

Up came Bobby Grich, fastball hitter against fastball pitcher. Crawford’s first pitch was a fastball sailing inside to the right-hander for ball one. The second pitch was a fastball that was not close to a strike, outside and away. With the count 2-and-0, Crawford needed to throw a strike as Grich would probably be taking a pitch. Crawford’s pitch was low and away for a strike, a borderline pitch, and he got the call. Crawford’s nerves were apparent; he was taking heavy breaths between pitches. On Crawford’s next pitch, Grich fouled the ball into the stands. With the count 2-and-2, Crawford threw a fastball tailing in on Grich, who hit a soft liner to Crawford who reached to his left to make the catch, ending the inning and extending the game and the Red Sox season. “That was the biggest thrill in my baseball life, getting out of that jam,” Crawford said.26

In the bottom of the 10th, with the score still 6-6, Crawford came out to face Reggie Jackson. Jackson worked the count to 3-and-2 before grounding out. Devon White struck out swinging. Crawford then walked Jerry Narron on four pitches. Gary Pettis worked a 3-and-2 count and drove a ball to deep left field. Jim Rice took a bad turn, backed up against the wall, and reached over his head to catch the ball for the third out. The Red Sox went on to take the lead in the top of the 11th inning. Schiraldi came in to pick up the save and give Crawford the win. After the game, Crawford revealed the pressure he felt during the game, saying, “If there was a toilet on the mound I would have used it.”27 Summing up the moment, he said, “There is nothing like being in game like this, the atmosphere is just terrific. It was a dream come true and it was the game of my life.”28

The Red Sox took the series in seven games and went on to play the New York Mets in the World Series. Boston won Game One and Game Two featured a pair of Cy Young Award winners, Roger Clemens and Dwight Gooden. Boston led 6-2 in the top of the fifth when Clemens faltered. With runners on first and third with one out, Crawford was called in. Gary Carter drove in a run with a single but Crawford struck out Darryl Strawberry and got Danny Heep to ground out to avoid further damage. In the top of the sixth inning, Crawford battled for the first time in the major leagues against Rick Aguilera. He popped out to Strawberry. In the bottom of the sixth, Crawford got the side in order. The Red Sox went on to win, 9-3, and Crawford picked up the win.

Crawford also pitched in Games Four and Seven. He did not fare well, giving up home runs to Lenny Dykstra and Gary Carter. In his three World Series games Crawford had a 1-0 record with a 6.23 ERA in 4⅓ innings of work, striking out four. The 1986 postseason would be the highlight of Crawford’s career.

As had been the case in the prior seven years, Crawford came to spring training in 1987 having to prove himself and he was growing a bit tired of it. “I’m the Rodney Dangerfield of the team,” he told a sportswriter. “No matter what I do the year before, I get no respect. Why is it every time I come to camp, I have to worry about winning a job or being traded? I’ve been coming here for seven years and it’s always the same and I’m sick of it.”29 Crawford also wanted to know what his role was. “I’d like to know whether I’m a long man, middle man, short man or starter.”30 Crawford did not want to leave the Red Sox, but he was growing frustrated; he would be 29 years old in April and no longer the prized prospect with high potential.31

The season was not a good one for Crawford; he was 5-4 with a 5.33 ERA and no saves. He went on the disabled list and had bone chips removed from his elbow for a second time. He opted for free agency at the end of the season and signed with the Cleveland Indians but was released before the season began. He signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers and spent the entire year in the minor leagues, first with in Double A with the San Antonio Missions of the Texas League and then in Triple A with the Albuquerque Dukes of the Pacific Coast League. The Dodgers released him at the end of the season.

The 30-year-old veteran worked hard during the offseason to save his career, working out with his friend, neighbor, and former Red Sox teammate Marty Barrett. Crawford called 20 teams in the offseason for a job and they all said they were all set. He went to Florida looking for a job. “I finally decided to just come down here to Florida and call these teams again,” Crawford said. “A friend of mine, a cop from Duxbury, let me use his house in Winter Haven. I flew down here on my own and just started calling. I told these people, ‘Look, I’m just asking for 20 minutes of your time.’ “32

The Kansas City Royals were looking for middle-relief help. After throwing 20 minutes to the pitching coach, Crawford signed a minor-league contract. He was a long shot to make the club. “I’m really hoping he does well,” Barrett said. “It has to have been humiliating for him, making all those calls, going from making $450,000 a year to just calling around and asking for a tryout. If he hadn’t come down here, just asking, I don’t think anyone would have called.”33

Crawford started the 1989 season in Triple A, with Omaha. One of his teammates was Donnie Moore, the losing pitcher of the 1986 ALCS Game Five. The two became friends before Moore was released and took his life on July 18, 1989.

Crawford was recalled to the Royals and pitched in his first major-league game in more than a year on July 5. He had one of his better seasons, going 3-1 and posting a 2.83 ERA. Crawford pitched two more seasons with the Royals and was released at the end of the 1991 season. He attempted a comeback during the lockout in 1995 but decided to retire for good, because he did not want to be called a scab.

Crawford stayed with the Royals, doing pregame and postgame shows on Kansas City radio station WDAF. He enjoyed doing radio and, in his words, “raising cain with former teammates such as George Brett.”34 He moved back on the field as a minor-league pitching coach in the Royals organization from 1995 to 2001. He gave it up because, in his words, the game had changed. “Being a pitching coach became more of a business aspect with the computer than teaching,” he said.35 Also, Crawford was injured when he was struck by a truck and hurt his right arm limiting his ability to help.

Crawford and his first wife, Debbie, had a daughter, Ashley, and two sons, Blake, and Casey. Blake grew to 6-feet-8 and played forward for the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Casey was State of Kansas “Mr. Basketball” his senior year in high school and 2006 Kansas Gatorade Player of the Year. Casey played forward at Wake Forest, then transferred to the University of Colorado. After graduation he played professionally in England, Japan, and Canada. Crawford had a daughter, Jade, with his second wife, Ingrid.

Until 2014, Crawford owned Crawford Pro Sports in Pryor, Oklahoma. As of 2015, Crawford is living in Claremore, Oklahoma with his wife and high school love Becky (Phillips). The couple has six children between them including Lacey and Austin. He found satisfaction in teaching youngsters how to pitch, when coaches ask him how much he charges, Crawford said, he tells them, “Buy me a Coke and we’ll be OK.”36

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Notes

1 Author’s interview with Steve Crawford on August 20, 2015 (Hereafter Crawford interview).

2 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford’s Big Chance; Sox Rate Him as Top Prospect,” Boston Globe, February 28, 1981.

3 Leigh Montville, “Salina’s Rocket Is Taking Off,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1981.

4 Crawford interview.

5 Crawford interview. Some think the nickname came from former National League umpire Shag Crawford (1956-1975).

6 Joe Giuliotti, “Torrez’s Misery is Almost Over,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1980: 21.

7 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford gets off to a Good Start,” Boston Globe, September 19, 1980.

8 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford’s Big Chance; Sox Rate Him as Top Prospect.”

9 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford’s Big Chance; Sox Rate Him as Top Prospect.”

10 Peter Gammons, “The Forgotten Arm; Crawford, Once Phenom is Fighting Back,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1984.

11 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford’s Big Chance; Sox Rate Him as Top Prospect.”

12 Larry Whiteside, “Sox Lose to Orioles, But Crawford Shows He’s for Real,” Boston Globe, April 14, 1981.

13 “American League Flashes,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 25.

14 Joe Giuliotti, “Experienced Houk Anxious for ’82,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1981: 57.

15 Peter Gamons, “The Forgotten Arm; Crawford Once Phenom is Fighting Back”, Boston Globe, March 3, 1984.

16 Larry Whiteside, “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s Sox Sleeper; Crawford Loses to Win,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1983.

17 Joe Giuliotti, “Crawford’s Attitude Key to Return,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1984: 25.

18 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford Earns Relief” Boston Globe, May 9, 1984.

19 “Crawford Earns Relief”.

20 Joe Giuliotti, “A Crawford Trade Is Taken Off Hold,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1985: 15.

21 Larry Whiteside, “Crawford Finds a Niche,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1985.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Joe Giuliotti, “Crawford May Be Sox’ Short Stopper,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1985: 18.

25 The complete November 13, 1985, transaction had the New York Mets receiving Chris Bayer, Tom McCarthy, John Mitchell, and Bobby Ojeda and the Boston Red Sox receiving John Christensen, Wes Gardner, Calvin Schiraldi, and La Schelle Tarver.

26 Michael McKnight, “The Split,” Sports Illustrated, October 4, 2014.

27 Ibid.

28 Mike Tully, United Press International, October 12, 1986.

29 Joe Giuliotti, “Crawford Seeks a Title,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1987: 18.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Leigh Montville, “Hitting Home,” Boston Globe, March 28, 1989.

33 Ibid.

34 Crawford interview.

35 Crawford interview.

36 Crawford interview.

Full Name

Steven Ray Crawford

Born

April 29, 1958 at Pryor, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.