Yogi Berra

Many images come to mind when one hears the name Yogi Berra. One of the more obvious is that of a winner. Berra won three American League Most Valuable Player awards and appeared in 14 World Series as a player and another five as a manager or a coach. He won 13 championship rings and holds several Series records. Berra met with numerous roadblocks on his journey to fame, but he overcame them with grit and dedication and went on to become one of the more beloved figures in American sports history.

Berra’s father, Pietro, arrived in New York on October 18, 1909, at the age of 23. He had left Robecchetto, Italy, a town about 25 miles south of Milan, where he was a tenant farmer. Pietro left behind Paolina Lingori, a young girl whom he planned to marry after earning enough money to pay her way to the United States. Paolina Longoni (subsequently, Paulina) arrived on March 10, 1912, aged eighteen. Peter and Paulina married nine days later and settled in a largely Italian section of St. Louis called “The Hill.”

Their first child, Anthony, was born in 1914. The second child, Mario, was born in Malvaglio, Italy, as Paulina, pregnant and homesick, went back to her hometown in 1915 for a visit. While she was there, World War I escalated and mother and child did not return to the United States until September 3, 1919. The Berras had a third son, John, in 1922, and on May 12, 1925, Lorenzo Pietro came into the world. His parents’ desire to assimilate in their new homeland led them to the English translation of Lawrence Peter, which, due to their accent, they pronounced Lawdie.

Lawdie Berra and his family lived on 5447 Elizabeth Avenue, across the street from Giovanni Garagiola and his family; they had a boy named Joe who was Lawdie’s age. The two youngsters spent most of their time playing games with the other neighborhood boys and their favorite sport was baseball. Besides sports, the boys loved to go to the movies. One day they watched a feature that had a Hindu fakir, a snake charmer who sat with his legs crossed and wore a turban on his head. When the yogi got up, he waddled and one of the boys joked that he walked like Lawdie. From then on Berra was known as Yogi. Even his parents called him by his nickname.

As a youngster Berra displayed the stubbornness and determination that carried over to his playing days. This was no more in evidence than when he decided he was going to quit school after the eighth grade. Yogi had never been a very good student and he felt he was wasting his time in school. Pietro disapproved, and enlisted the aid of the school’s principal and the local parish priest to help keep his son in school. Yogi held firm, and eventually his father relented and Yogi went to work in a coal yard. He lost the job because he often left work early to play ball with his friends after they got out of school. Pietro, furious his son would lose a job that paid $25 a week, was able to get Yogi a job working on a Pepsi Cola truck that paid $27 a week. He was fired from that job as well. After much arguing, it was decided Yogi would find a job that would allow him to play ball in the afternoon.

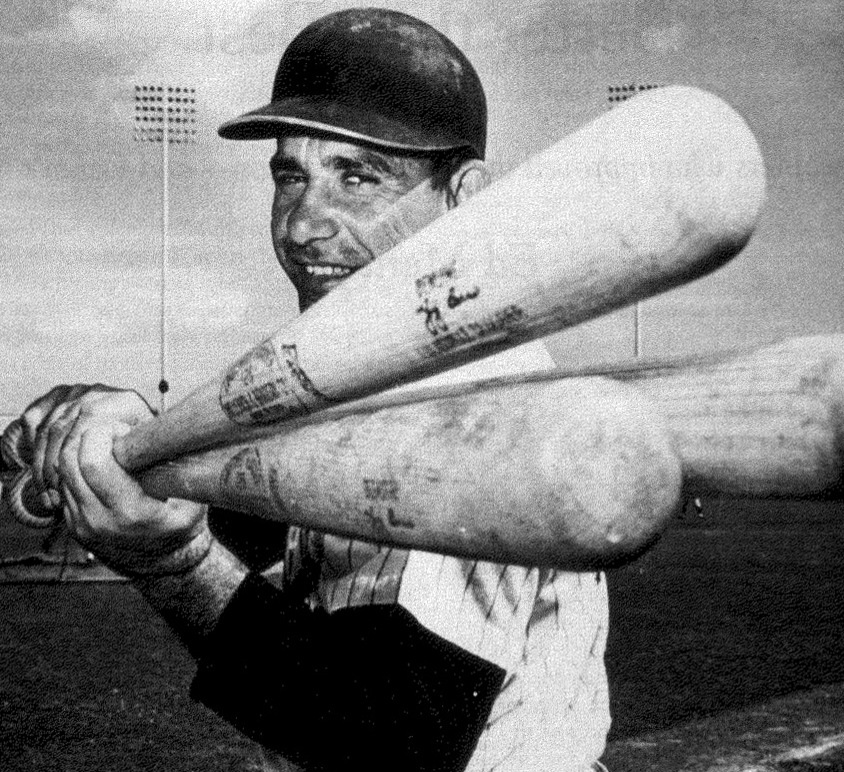

Yogi and Joe Garagiola were stars on an American Legion team that made the playoffs two consecutive years. Garagiola was six feet tall, athletic, and handsome. By contrast Berra, at 5-feet-7 and 185 pounds, was short and dumpy and had an awkward swing in which he chopped at the ball. He would also swing at anything near the plate. The man who ran the team, Leo Browne, arranged a tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals for his star players. Garagiola did well and was offered a contract with a $500 bonus with the order to keep quiet about it until he turned sixteen (the boys were fifteen at the time).

Despite not having a particularly good tryout, Berra was offered a contract but no bonus. Berra knew he could not go home without the same bonus as Garagiola, so he refused the offer. Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey offered a $250 bonus and again Berra refused. Yogi later had a tryout with the St. Louis Browns and once more was offered a contract without a bonus; once more he turned it down.

Browne wrote to his old friend George Weiss, who was in charge of the New York Yankees’ farm system. He said all Yogi wanted was a $500 bonus and whatever he made a month was fine. Berra signed with the Yankees in October 1942 for the $500 bonus he so adamantly desired, plus a monthly salary of $90. Rickey, now with the Dodgers, sent Berra a telegram offering him a chance to sign with Brooklyn but Yogi never responded because he was the property of the Yankees. So Yogi Berra was off to Norfolk, Virginia, to begin his professional baseball career.

Berra batted .253 in 111 games for the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars in 1943, with seven home runs and 56 runs batted in. After the season Berra enlisted in the navy. He became a machine gunner and saw action on D-Day aboard a rocket boat deployed just off the Normandy coast before the soldiers assaulted the beach. Berra spent 10 days on the 36-foot boat before he finally returned to his ship, the USS Bayfield, an attack transport.

Before he was discharged, Berra was shipped to the submarine base at Groton, Connecticut. He played for the base’s baseball team, managed by Lieutenant Commander James Gleeson, a former big-league outfielder. Gleeson had a difficult time believing the squat, awkward-looking seaman was a professional ballplayer, much less property of the Yankees. But in a game between the sailors and the New York Giants, Berra went 3-for-4 and impressed Giants manager Mel Ott so much he called the Yankees and offered $50,000 for Berra. Yankees president Larry MacPhail turned Ott down. Years later MacPhail confessed he had never heard of Yogi, but if Ott thought he was worth that kind of money, then the Yankees should keep him.

In 1946 the Yankees assigned Berra to the Newark Bears of the Class Triple-A International League, managed by former Yankees All-Star George Selkirk. Like Gleeson before him, Selkirk was skeptical that this squat young man was a ballplayer or a Yankee. He forced Yogi to show him the telegram from MacPhail ordering him to report to Newark.

Berra played in 77 games and batted .314 with 15 home runs and 59 RBIs but displayed an erratic arm behind the plate. In the regular-season finale, Berra tied the game with a ninth-inning homer, a game that Newark eventually won. The victory put Newark in the playoffs for the 14th consecutive season, though the Bears lost to a Montreal Royals squad that included Jackie Robinson.

After the loss to Montreal, Berra was called up to the Yankees and made his major-league debut on September 22, 1946, against the Philadelphia Athletics. He went 2-for-4, with a home run off Jesse Flores in his second at-bat. His second home run came the next day.

At spring training in 1947, Berra played mostly in right field, where he showed little skill. He was, however, earning a reputation as a hitter, although one who would often hit pitches well out of the strike zone. Because of Berra’s erratic outfield play, he saw more time at catcher once the season began; this seemed to be the safest place for him to play.

On June 15 he made an unassisted double play in a game against St. Louis. A week later he hit his first grand slam in a win over Detroit, and when he homered again the next day, he had registered six RBIs in two games. On August 26, a group from “The Hill” organized Yogi Berra Night in St. Louis to honor their native son. Before the series in St. Louis, Berra had contracted strep throat in Cleveland and had to be hospitalized. When he arrived in town for his night, Yogi was very nervous about making an acceptance speech. That was the night he uttered the famous line, “I want to thank everyone for making this night necessary.”

Berra batted .280 in his rookie campaign, with 11 home runs and 54 RBIs in 83 games. The Yankees faced Brooklyn in the World Series, the first fall classic to be televised. Yogi went 0-for-7 in the first two games, but came off the bench in Game Three to hit the first pinch-hit home run in Series history. Overall, he was 3-for-19 as New York won in seven games.

Berra spent the offseason in St. Louis, where he met a pretty waitress named Carmen Short working at a restaurant co-owned by Stan Musial. Yogi and Carmen hit it off and six months later were engaged. They were married on January 26, 1949, and old pal Joe Garagiola served as best man.

In 1948, Berra had a strong year at the plate, batting .305 with 14 home runs and 98 RBIs while appearing in 125 games (71 as a catcher). The All-Star Game was played in St. Louis that year; Berra made the squad but did not play. The Yanks finished third behind Cleveland and Boston and entered the off-season in the market for a better defensive catcher. This changed when the Yankees surprised the baseball world by picking 58-year-old Casey Stengel as their manager; Stengel nixed any thought of replacing Berra behind the plate.

Casey took an immediate liking to Berra, calling him “my assistant manager.” Stengel had an idea Yogi was much more sensitive than he let on, and decided to act as a buffer against those who criticized or just made fun of his young catcher. He also assigned future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey to act as Berra’s personal tutor. Dickey spent hours working with his student to improve his mechanics behind the plate and teaching him to think ahead during games.

Despite the improvement in his defensive play, Berra had some trouble with Yankees pitchers, especially Vic Raschi and Allie Reynolds, who thought he smothered curve balls and stabbed at fastballs, and thus made it difficult to get close calls from umpires. For his part, Stengel did not yet completely trust Berra either. In some critical situations the manager would call the pitches from the dugout, infuriating the veteran pitchers. Finally, one day in a game against the Athletics, Reynolds had enough. Stengel began waving to Yogi to get his attention so he could call a pitch. Meanwhile, Allie warned his young catcher if he looked into the dugout he would cross him up intentionally.

Berra knew this was not an idle threat and ignored his manager at the risk of being fined. The incident proved to be a turning point in his relationship with the pitching staff; they now felt that they could trust Berra. The season ended with the Yankees sweeping a two-game series against the Red Sox to claim the pennant. Yogi was a disappointing 1-for-16 in the World Series, though the Yanks beat Brooklyn in five games.

By the next season, Berra had established himself not only as a legitimate big-league catcher but also as a rising star in the American League. He had a stellar season in 1950, batting .322 with 28 home runs and 124 RBIs as the Yanks swept the Philadelphia Phillies to win their second straight world championship. After finishing third in the 1950 AL MVP voting, Berra won his first Most Valuable Player Award in 1951, when he led New York to yet another World Series title, this time at the expense of the New York Giants.

The next two seasons were more of the same as the Yanks won their fourth and fifth consecutive titles with wins over Brooklyn. Berra continued to develop his reputation as a clutch hitter, driving home 98 runs in ’52 and 108 in ’53. He batted a robust .429 in the Yankees’ six-game World Series victory in ’53. A second MVP came in 1954 despite the Cleveland Indians temporarily interrupting the Yankees dynasty. That year Berra batted .307 with 22 homers and 125 RBIs.

Berra entered the 1955 season as the highest-paid Yankee, and he earned his $48,000 by winning his second consecutive MVP award and third overall. The season ended in disappointment, however, as the Dodgers were finally able to take a Series from the Yankees. Jackie Robinson stole home in Game One, and Berra argued the call vociferously while jumping up and down. He never stopped insisting Robinson was out and he even signed photos of the play, “He was out.” In the decisive seventh game, Yogi came to the plate in the sixth inning with two men aboard and hit a fly ball toward the left-field corner, but left fielder Sandy Amoros raced over, made a spectacular catch, and turned it into a double play.

The Yankees regained the world championship in 1956 — against the Dodgers — and Berra had a big Series with three home runs, including two off Don Newcombe in the decisive seventh game. Berra batted in 10 runs, yet the highlight of the Series for him was catching Don Larsen’s perfect game in Game Five. Larsen said he did not shake off Berra once during his masterpiece.

Berra slumped to a .251 average in 1957 but was still productive with 24 home runs and 82 RBIs. He followed that with a similarly productive 1958 with a .266 batting average, 22 homers, and 90 RBIs. In those two seasons the Yankees and Milwaukee Braves split the World Series; Milwaukee won in 1957, and New York won in 1958.

The 33-year-old Berra reached some milestones in 1959, including his 300th career home run. He also set records (since broken) for the most consecutive chances by a catcher without an error, and the most consecutive games without an error. The erratic catcher of the early years was now a distant memory.

Though the Yankees didn’t win the pennant in 1959, they did win in 1960, the tenth and final flag under Casey Stengel. Yogi played more in the outfield, appearing in only 63 of 120 games as a catcher. In the thrilling Game Seven against Pittsburgh he hit a three-run homer in the sixth inning that only served as backdrop to Bill Mazeroski’s Series-ending home run in the ninth inning. That fabled shot sailed over left-fielder Berra’s head.

Yogi played three more seasons before retiring after the 1963 World Series. He batted just once in the Series, a sweep at the hands of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Even with that loss, he finished with a 10 4 record in Series play. He was named an All-Star 18 times between 1948 and 1962 (including four years when two All-Star Games were played each summer). He started behind the plate for the American League 11 times.

Berra had a career batting average of.285, with 358 home runs. At the time of his retirement, his 306 homers as a catcher were the most ever at the position. He still holds several World Series records, including the most games played (75). In his 18-year career, he drew 704 walks against just 414 strikeouts — proof that this legendary bad-ball hitter indeed hit what he chased.

On October 24, 1963, Berra was named the Yankees’ manager to replace Ralph Houk after Houk became general manager. The Yankees offered Berra a two-year contract but he insisted on a one-year deal as he was not sure he could manage. He would later regret that decision. Berra had intended to keep pitching coach Johnny Sain on his staff, but Sain could not agree on a contract and Berra turned to old friend Whitey Ford to be a player coach. He always believed Ford was one of the more intelligent pitchers and thought he would be outstanding in handling young pitchers.

The 1964 Yankees were not an easy bunch to manage. Veterans Mickey Mantle and Ford were famous for their off-the-field drinking and carousing, and the young players wanted to follow along. Players like Jim Bouton and Joe Pepitone were brash, and the clubhouse was out of control.

The Yankees came out of the gate sluggish, but by early August, Berra somehow had them in first place. Yet they spent the rest of the month playing uninspired and inconsistent ball. The nadir came in mid-August with a four-game sweep at the hands of the Chicago White Sox that dropped them 4 1/2 games behind the first-place White Sox. After the series concluded, the team bus was stuck in traffic on the way to the airport and everyone was feeling impatient.

It was then that one of the more memorable incidents of Berra’s stewardship took place. Infielder Phil Linz pulled out his harmonica and began to play “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Berra angrily yelled from the front of the bus for him to stop. There are different accounts of what happened next.

According to Mantle, Linz asked him what Berra had said. Mantle reportedly responded, “Play louder.” Linz obliged. When Yogi heard the harmonica again he stormed to the back of the bus, smacked the instrument away, and a heated argument ensued. When news of the confrontation came out, Houk told reporters he had no intention of speaking to Berra about the incident. With Berra’s job security already in danger, this appeared to make his firing a fait accompli.

The Yankees lost the next two games to Boston to fall six games behind but then came on with a rush. They finished August strongly and went 22 6 in September before clinching the pennant on October 3. Their opponent in the World Series was the St. Louis Cardinals, who had also rallied to claim a thrilling National League race.

It was a back-and-forth Series that came down to a seventh-game matchup between Cardinals ace Bob Gibson and 22-year-old Mel Stottlemyre. St. Louis broke through for three runs in the fourth inning with the aid of some sloppy New York defense and Gibson held on to clinch the Series.

Overall, Berra had done a good job with an aging team. Ford had a sore arm and Mantle’s bad legs were making it increasingly difficult for him to cover center field. It was Berra who pushed for Stottlemyre to be called up in mid-August, and the rookie came through with a 9 3 record. It is unlikely the Yankees would have won the pennant without the young right-hander. They had responded well after the Linz episode and Yogi had every intention of asking for a two-year extension. Instead, he was fired and offered a job as a scout.

Across town, the New York Mets had finished their third season of play and two former Yankees were running the show, general manager George Weiss and manager Casey Stengel. With wife Carmen advocating he break with the Yankees after their shabby treatment of him, Berra took Weiss’s offer and joined Stengel’s staff as a player-coach. He caught only two games and batted .222, playing his final game three days before his 40th birthday in May.

Berra stayed with the Mets even though he was passed over for manager on three occasions. The first was when Stengel retired after breaking his hip in August 1965 and the Mets — with Stengel’s input — chose Wes Westrum as his replacement. Salty Parker was tabbed as Westrum’s interim replacement when he resigned in the final week of the 1967 season. In October 1967 the Mets dealt for Senators manager Gil Hodges to replace Parker. Berra knew and respected Hodges and was not upset at being passed over in favor of his old Dodgers rival.

So Berra stayed on to coach under Hodges and won his 11th World Series ring in 1969 when the Miracle Mets upset the Baltimore Orioles. Berra’s opportunity to finally manage the Mets came under tragic circumstances. He replaced Hodges when the Mets manager died of a heart attack on April 2, 1972, after playing golf.

Although Berra had coached under Hodges for four years, he was a different type of manager. Hodges was a disciplinarian who took a more hands-on approach with his players. By contrast, Berra treated his players as adults and left the responsibility of being in shape to them, figuring that just being a ballplayer should be motivation enough to take your job seriously and be prepared. Unlike his predecessor, Berra did not platoon and kept the same lineup, a change the veterans found to their liking.

The Mets were 30-11 on June 1, but beset by injuries they staggered to a third-place finish. On a brighter note for Berra, that summer marked his induction into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

In 1973 injuries slowed the Mets again and there were rumors that Yogi might not make it through the summer. The team was in fifth place at the end of August, but as players regained their health, the Mets closed the gap in the tightly-bunched National League East.

On September 21 the Mets reached .500 and first place at the same time. With a victory over the Cubs on October 1, the Mets completed their remarkable comeback, winning the division title with just eighty-two victories. They defeated the highly-favored Cincinnati Reds in the National League Championship Series, making Berra only the second manager to win a pennant in each league (Joe McCarthy was the first). In the World Series, the Mets lost to the Oakland A’s in seven games.

The Mets fell to fifth place in 1974 with a 71 91 record, the club’s worst mark since 1966. Simmering trouble between Berra and left fielder Cleon Jones deepened in 1975 and when Jones refused to enter a game as a pinch-hitter, matters came to a head. Yogi refused to let Jones back on the team and demanded he be released. Chairman of the board M. Donald Grant did not want to cut Jones, but Berra remained firm and soon thereafter Jones was waived. The team was struggling and when it suffered a five-game losing streak in early August — culminating with a doubleheader shutout at home at the hands of the last-place Expos — Yogi was fired. Coach Roy McMillan was picked to replace him.

After a 12-year absence, Yogi returned to the Yankees when old friend and teammate Billy Martin picked him to be on his staff in 1976. With Berra on board at the reopened Yankee Stadium in 1976, the Yanks won their first pennant since 1964. Though they were swept in the Series by the Reds, Berra added two more World Series rings with back-to-back titles in 1977 and 1978. Berra was a constant on the Yankees’ coaching staff through the 1983 season despite several managerial changes. He got one more chance to manage when he was named Yankees manager for 1984.

New York struggled early in the season and there was no catching the Detroit Tigers, who cruised to the division title. Prior to the ’85 season, rumors swirled that owner George M. Steinbrenner wanted to fire his manager, but as spring training came around he declared Berra safe for the year. This was a season Yogi looked forward to because the Yankees had acquired his son Dale from Pittsburgh. Not only did Berra not survive the season but he was fired before the end of April with a record of 6 10. Upset that Steinbrenner broke his promise to let him manage the entire year, Berra stayed away from Yankee Stadium until reconciliation in 1999.

While his managing days were now over, his coaching career was not. Houston Astros owner John McMullen offered Berra the Astros’ manager position just three days after he was fired but he turned it down. At the end of the season, he did accept a coaching job with Houston under rookie manager Hal Lanier. Yogi stayed with the Astros through the 1989 season, ending his long and illustrious career in uniform. He had spent seventeen years as a player, two years as a player-coach, eighteen years as a coach, and seven years as a manager.

Berra remained not only a Yankees legend but an American icon as well. A museum dedicated to him opened in Montclair, New Jersey, his and Carmen’s home for more than half a century. There they raised their three sons: Larry, a former minor-league catcher; Tim, who played in the NFL for the Baltimore Colts in 1974; and Dale, who spent the last couple of months of his 11-year career with his dad on the 1987 Astros.

Yogi promoted numerous products — most famously Yoo-Hoo, the chocolate soft drink, and even had a cartoon bear named after him. The former catcher’s Yogi-isms are known worldwide. As one of the oldest and most recognizable Hall of Famers, Yogi Berra maintained a connection back to what many consider the Golden Era of baseball.

He died at the age of 90 on September 22, 2015.

Sources

DeVito, Carlo. Yogi: The Life and Times of an American Original. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008.

Lang, Jack, and Peter Simon. The New York Mets: Twenty-Five Years of Baseball Magic. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1986.

Hernandez, Keith, and Matthew Silverman. Shea Good-bye: The Untold Story of the Historic 2008 Season. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009.

Palmer, Pete, and Gary Gillette (editors). The 2005 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Sterling, 2005.

http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/ber0int-3

Author interview with Jerry Koosman, December 16, 2008.

Full Name

Lawrence Peter Berra

Born

May 12, 1925 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 22, 2015 at West Caldwell, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.