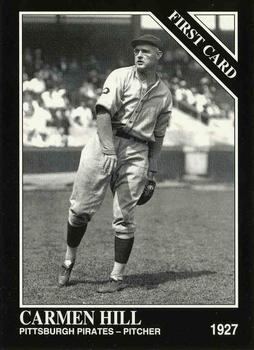

Carmen Hill

Relentless desire and unshakable determination define Carmen Hill’s 17 years in Organized Baseball. In 1915, the 19-year-old bespectacled hurler jumped from a Class B league to debut with the Pittsburgh Pirates, becoming the just the second major-league pitcher to wear glasses on the diamond in more than a quarter-century. For 12 years, Hill endured a grueling journey, both mentally and emotionally taxing, involving six brief look-sees on big-league clubs, trades, suspensions, debilitating injuries, and personal tragedy. He finally stuck for an entire season at age 31, winning 22 games and helping the Pirates to the NL pennant in 1927. “Hill’s career is proof that he is a persistent and conscientious worker,” declared Smoky City sportswriter Lou Wollen. “He was confronted by obstacles and disappointments that would have discouraged any but a lion-hearted athlete.”1

Relentless desire and unshakable determination define Carmen Hill’s 17 years in Organized Baseball. In 1915, the 19-year-old bespectacled hurler jumped from a Class B league to debut with the Pittsburgh Pirates, becoming the just the second major-league pitcher to wear glasses on the diamond in more than a quarter-century. For 12 years, Hill endured a grueling journey, both mentally and emotionally taxing, involving six brief look-sees on big-league clubs, trades, suspensions, debilitating injuries, and personal tragedy. He finally stuck for an entire season at age 31, winning 22 games and helping the Pirates to the NL pennant in 1927. “Hill’s career is proof that he is a persistent and conscientious worker,” declared Smoky City sportswriter Lou Wollen. “He was confronted by obstacles and disappointments that would have discouraged any but a lion-hearted athlete.”1

Carmen Proctor Hill was born on October 1, 1895, in Royalton, Minnesota, a farming town of about 600 residents situated on the Platte River approximately 85 miles northwest of Minneapolis. His parents were Harry H. Hill, originally from Maine, and Myrtle J. (née Baxter) Hill, who married in 1882. They raised four children, all born in Minnesota between 1883 and 1895: George, Percy, Winnifred, and the youngest, Carmen.

In 1899 the Hills relocated to Myrtle’s hometown of Corry, Pennsylvania, in Erie County in the northwest corner of the state, where her parents had a farm. According to Hill’s short autobiographical booklet (whose title, The Battles of Bunker Hill, refers to one of his monikers), his mother despised the cold weather and snow in Minnesota and was afraid of the tornadoes that whipped up on the flat plains.2 Harry Hill, whose work in construction often required him to be away from home for weeks at a time, saw the move as an opportunity to settle down.

Before the family moved, young Carmen underwent a profound change. Like his three siblings, Carmen was left-handed; however, his grandfather vowed to change that. He took Carmen at the age of three to the Platte River, where he collected stones to skip in the water. “[W]hen I reached with my left hand for a stone,” recalled Hill, “he would slap my hand.”3 Eventually, Carmen became right-hand-dominant.

The Hills purchased a two-story house at 505 Wright Street in Corry, a bustling industrial and railroad town of 6,000 residents. Located near coal fields and the developing oil regions around Oil City, Corry was a prosperous shipping center and known for manufacturing limax steam locomotives. Father Hill’s work in carpentry and contracting provided the family a comfortable life.

A precocious youth, Carmen played the piano and sang, but especially enjoyed the outdoors and shooting his .22-caliber Winchester pump shotgun at targets at nearby farms. At the age of 10 he had an accident with lifelong ramifications. While playing in a barn with other boys, he fell 15 feet down a hay chute and landed in an awkward sitting position on a manger board and was knocked unconscious. With X-rays unavailable in Corry at the time, Carmen was prescribed rest. However, he learned as an adult that two vertebrae had fused, resulting in painful ankylosis, or stiffening, in his spine. While convalescing, he contracted malaria and was bedridden for several additional weeks.

Carmen attended the Corry grade school, which was next door to his house. His introduction to baseball was in the schoolyard and local sandlots. Hill recalled that he experienced a substantial growth spurt after his fall and bout with malaria, adding seven inches in about six or seven months when he was 12. Suddenly big for his age, Carmen developed into his school’s top player and pitcher by the eighth grade.

By the time he graduated from Corry High School in 1914, Hill was a hard-throwing pitcher with a burgeoning reputation in the local city league. He turned down an offer from the Philadelphia Phillies to leave school in March and participate in the club’s spring training in Wilmington, North Carolina.4 Another opportunity to showcase his talent occurred when the New York Giants played an exhibition game in Erie, the harbor town 40 miles from Corry. Through the connections of a family acquaintance, Hill was invited to toss batting practice to catcher Larry McLean. Impressed by the 18-year-old, McLean promised Hill that he’d tell skipper John McGraw, who had returned to New York, about his talent.5

Hill never heard back from the Giants. Pitching for the local Butter Krusts later that summer in Warren, 30 miles east of Corry, Hill was signed by William Webb, manager of the Warren Bingoes, in the inaugural season of the Class D Interstate League.6 He appeared in six games, thus commencing his career in Organized Baseball.

Despite Hill’s limited professional experience, the Pittsburgh Pirates offered him a contract in 1915 which began a turbulent and frustration-filled relationship with the club. According to Hill, the same acquaintance who had facilitated BP with the Giants knew Barney Dreyfuss, the owner of the Pirates.7

Just 19 years old, Hill immediately made news with his eyewear in the Bucs camp at Dawson Springs, Kentucky. The Pittsburgh Gazette Times called him a “novelty.”8 The last big-league pitcher to wear glasses was Will White, who had retired in 1886. Coincidentally, another bespectacled Class D pitcher, Lee Meadows in the St. Louis Cardinals camp, was also attempting to become the first hurler to sport “cheaters” on the mound in more than a quarter-century. Eyeglasses at the time were made of glass, not plastic, and carried a very real danger of permanently injuring the wearer if they were hit by a ball. References to his rimless, and typically tinted, spectacles accompanied Hill for the rest of his professional career. Many sportswriters, like Pittsburgh’s Ralph S. Davis, seemed astonished, noting that they “[do] not appear to handicap him in the least.”9 Described as “nervy” by Bucs beat writer Lou Wollen, Hill protected himself from batted balls by immediately whipping his glove hand in front of his face as soon as he delivered a pitch.10

Hill impressed skipper Fred Clarke, whose club was coming off a seventh-place finish yet had a robust pitching corps which had finished second in team ERA (2.70). Sportswriter Ed F. Balinger praised Hill’s “considerable smoke.”11 The Pittsburgh Dispatch predicted that he had a “bright future” given his command of three pitches: a “deceptive curve,” his heater, and a change-of-pace.12

Hill competed with another recruit, 24-year-old hard-throwing Dazzy Vance, for the eighth and final spot on the Pirates staff. Vance won (though he was sent to the minors after just one start). Thus, Hill was assigned to the Youngstown (Ohio) Steelmen in the Class B Central League. Emerging as a durable and effective workhorse against seasoned players, Hill exacted revenge against his former Pirates teammates by shutting them out on five hits in a 12-inning complete game in an exhibition in Youngstown on June 21.13 En route to a 19-12 record and 2.29 ERA in 291 innings, Hill tossed 18 scoreless innings against Grand Rapids on July 27, but lost a heartbreaker in the next frame, 3-2.14

Confident in their teenager’s future, the Pirates promoted Hill and dealt Vance to the Yankees.15 Hill was rudely welcomed in his debut, yielding three hits and three runs in four innings of relief in a 10-0 washout to the Braves in Boston on August 24. After yielding just one run in 17⅔ innings of relief, Hill earned his first start. In the second game of a twin bill against the Giants on September 17, Hill had a “brilliant” performance, as Pittsburgh sportswriter Charles J. Doyle accurately remarked. He tossed a four-hit shutout and retired the final 19 batters of the game.16

With his thin, round glasses, Hill appeared bookish and learned, and was once described as “look[ing] more like a college professor than … a ball player.”17 Ralph S. Davis quipped that Hill has “brains which are not constantly on vacation.”18 As he aged and his fastball faded, Hill developed a reputation as a cerebral pitcher and student of the game. By one account of Hill’s approach to baseball, “He studies batters, their weakness, the atmospheric conditions and numerous other minorities, and relies more on this knowledge than he does on sheer pitching stuff.”19

Hill had a serious temperament. In a nationally syndicated piece published later in his career, writer Cullen Cain described the pitcher as “somber, reserved, and even aloof to strangers, yet if one penetrates his confidence he finds and a deep, strong, earnest, admirable character.”20

The novelty of his glasses aside, Hill was “every bit an athlete,” declared beat writer Ed F. Balinger.21 Often described as a “giant,” Hill stood 6-feet-1, weighed 180 pounds, and was known to be in especially good physical shape. His endurance and durability on hikes at Dawson Springs and Hot Springs, Arkansas, with teammates were legendary. According to Balinger, Hill could trek 20 miles and barely break a sweat.

Coming off an impressive late-season look-see (2-1 with a 1.15 ERA in 47 innings), Hill faced stiff competition at the Pirates camp in Dawson Springs in 1916. The club returned its top five starters, Babe Adams, Bob Harmon, Wilbur Cooper, Al Mamaux, and Erv Kantlehner, the latter three each 24 years old or younger, and added highly touted prospect Burleigh Grimes. Relegated to the bullpen, Hill was thumped in two relief outings, yielding 10 runs, six earned, in 6⅓ innings. He was optioned to the Rochester Hustlers in the International League.

With the opportunity to start every four days against veteran competition, most of which had or would have major-league experience, Hill posted a deceptive 14-16 slate on a mediocre team (60-78) and finished runner-up to Urban Shocker for the ERA title with a career-low 1.92 in 258 innings.

Just weeks after the season’s conclusion, Hill experienced the traumatic death of his friend Lynn McLean, with whom he owned two pool halls.22 Wanting to check on their establishment in Union City, about 10 miles from Corry, the two men decided to jump a freight train. McLean went first, slipped, and was run over, dying instantly. A shaken Hill quit the billiard business.

In 1916 Hill married Ruth Johnson of Corry, two years his junior. They had three children, Paula, Carmen, and Clifford, born between 1917 and 1921.

Hill got another jolt in January 1917 when the Pirates sold him to the Birmingham Barons in the Class A Southern Association in partial payment for acquiring Burleigh Grimes. The transaction “probably ends for all time [Hill’s] connection to the Pittsburgh club,” proffered sports scribe Davis.23 The Pirates rued the decision. Hill tossed a two-hitter to beat his former club in an exhibition on April 7 in Birmingham.24 The 21-year-old exploded out of the gate, winning his first 12 decisions, culminating with a no-hitter with just one walk against Little Rock on July 30.25 En route to a league-high 26 wins while logging 320 innings, Hill was sold back to the Pirates in mid-August on scout Ray Miller’s recommendation.26

At the Pirates’ spring training in Jacksonville in 1918, Hill suffered a serious injury. “I was pitching in the sandy soil and suddenly stepped into a six-inch hole just as I released the ball,” he recalled. “I wrenched my back so badly that I could hardly walk to the clubhouse.”27 Diagnosed as “loose vertebrae,” the injury reaggravated the back problems he sustained as a youth.28 “I suffered relapses the rest of my career,” said Hill.29

Unable to pitch in any exhibition games,30 Hill was reassigned to Birmingham, though many wondered if baseball would even take place. America had entered the Great War and following Secretary of War Newton Baker’s “work or fight” decree, professional ballplayers enlisted en masse or worked in war-related industries. When the Southern Association suspended its season on June 28, Hill was transferred to Kansas City in the American Association for three weeks before that league also suspended operations. Despite his combined 10-10 record and 2.98 ERA in 163 innings, Hill developed arm pain and troubles from overcompensating for his back injury.31

Hill was in Corry preparing to assume a wartime job with Allegheny Steel in the Pittsburgh area when the Pirates informed him to report to the club.32 Meeting his teammates in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on July 28, Hill tossed a complete game against the Americans in the Class B Eastern League, but the Pirates lost 2-1 in 10 innings.33 Hill shored up skipper Hugo Bezdek’s injury-riddled staff. He debuted on August 9, hurling five scoreless innings of relief against the Cincinnati Reds at Forbes Field and picking up the win. The Pirates bounced back from a dreadful season to finish in fourth place (65-60) in a shortened season. Hill (2-3, 1.24 ERA in 43⅔ innings) demonstrated yet again that he had the stuff to compete in the majors.

Hill’s patience was wearing thin after five years in the Pirates organization. When the team informed him that he would be assigned to the minors again in 1919, he quit and signed with an independent semipro team in Oil City in the Two-Team League, managed by former Pirates second baseman Jake Pitler.34 Hill eventually returned to the Pirates in mid-May, but was in noted disciplinarian Bezdek’s doghouse and relegated to the far end of the bench. Hill was clobbered in four relief appearances. In early July the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association purchased Hill’s contract on skipper Jack Hendricks’ recommendation, thus ending the pitcher’s tenure with the Pirates for a second time.35

Despite his success (14-9) with the Indians, Hill refused to return to the club the next season because of a salary dispute. He was suspended from Organized Baseball.36 He had developed painful stomach ulcers late in the season which made pitching difficult. In addition, his right arm ached. “I had pitched with an arm that would not extend over three-fourths straight,” recalled Hill of his 1918 and 1919 seasons. The buildup of bone spurs, which Hill thought resulted from throwing curveballs, was finally loosened in an odd accident in his garage. “One day I put the motorcycle crank on compression and started to turn it, when the crank slipped off. My arm popped like a pistol. By small jerks, my arm drew up until my hand touched my shoulder.”37 Several days later Hill’s arm began to straighten and remained so the rest of his career.

Hill’s health had improved greatly by the summer of 1920, enabling him to resume pitching for Pitler’s Oil City club.38 The following season he pitched for the semipro independent Zanesville Mark Grays.

While working at the Pennsylvania Terminal shop in Canton in the offseason, Hill received a telegram from the Indians offering to pay his $500 reinstatement fine.39 He accepted and reported to spring training in Plant City, Florida. The 26-year-old hurler showed no signs of rust, putting up solid numbers (15-12, 3.26 ERA in 210 innings), and catching a much-needed break. Indians owner William C. Smith, who was friends with John McGraw, sold Hill to the Giants on August 28, just in time for Hill to be on the World Series roster. En route to their second straight title, the Giants had an injury-decimated staff. Hill went 2-1 in eight mainly rocky appearances, logging 28⅓ innings. Hill pitched batting practice in the World Series, but did not see any game action, as Little Napoleon used only five hurlers in the club’s sweep of the New York Yankees in five games (Game One was a tie).

Returned to the Indians in the offseason, Hill patiently waited for another shot on the big stage. Over the next three seasons (1923-1925), he lost more games than he won (45-50) while logging about 250 innings per season. In July 1925 he endured an unimaginable tragedy when his youngest child, four-year-old Clifford, was run over and killed while exiting Hill’s car in Indianapolis.40

With his chances of returning to the majors slipping away, the 30-year-old Hill had his best season with the Indians in 1926, going 21-7. On September 1 the Pirates bought his contract for a reported $50,000.41 (The Pirates eventually sent Louis Koupal and Walter Mueller to the Indians in November to complete the deal.)42 Skipper Bill McKechnie’s reigning World Series champions were just a game off the lead to start the month in a tight three-team pennant race; however, the club was racked by internal strife43 and plagued by an injury-depleted staff. In a “masterly debut,” according to Bucs beat writer Charles J. Doyle, Hill tossed a 10-inning complete game and knocked in the game-winning run against the Cubs on September 3.44 The Pittsburgh Press remarked that he was “cool and collected at all times [and] displayed a fine fast ball and good curve.”45

Hill made history in his next start on September 8 against the Reds at Forbes Field when he and teammate Lee Meadows became the first set of bespectacled pitchers to start a doubleheader in baseball history. Hill tossed a nine-hit shutout, also getting two hits and knocking in a pair to complete the twin-bill sweep for the slumping Pirates. The club went 13-17 in the month to finish in third place, while Hill (3-3 with four complete games in six starts) proved to be a pleasant surprise.

Beginning his 14th season of professional baseball, Hill was well positioned to finally spend his first full campaign in the majors when he reported to the Pirates’ spring-training site in Paso Robles, California, in 1927. However, in a cruel turn of events, Hill developed a sore arm in camp. Donie Bush, Hill’s previous skipper with Indianapolis, who had replaced McKechnie, nonetheless retained confidence in his former ace. Bush “insisted that Hill would win many games,” reported Charles J. Doyle.46 Bush’s trust seemed misplaced when Hill was hit hard in his first three starts, losing two of them, giving rise to rumors that he would be shipped back to Indianapolis.

Still plagued by arm pain in early May, Hill went to Guy Greene, a chiropractor in Linesville, Pennsylvania, about 100 miles north of Pittsburgh.47 Greene, who had treated other ailing Pirates, made adjustments to Hill’s shoulder, spine, and elbow – and suddenly the pain dissipated.48

Greene’s deft hands helped. On May 21, Hill tossed a complete game to beat the Giants in the Polo Grounds. His first victory of the season began a torrid streak: eight straight decisions and 14 of 15 through July 24. Lauded as the “bright star of the Buccaneer staff, Hill emerged as one of the hottest pitchers in baseball and picked up the slack when Ray Kremer, who had tied for the NL lead with 20 wins in 1926, was shelved with arm miseries.49 More importantly, Hill helped propel the Pirates into first place and build a five-game lead in June.

Hill’s excitement did not occur just on the field. The night before taking the mound against the Reds in Pittsburgh on July 1, Hill and his catcher, Earl Smith, were invited to go to a club on the city’s south side. They were ushered to a back room and served real beer despite Prohibition.50 According to Hill, he was approached by a “peg-legged man” and offered $6,500 to throw the game. Laughing, Hill blurted out, “Make it $10,000.” When the man left to see if he could up the ante, a spooked Hill grabbed Smith and left the bar. “We went home and got our pistols and went back,” recalled Hill, but the gambler had disappeared.

“Without Carmen Hill the Pirates would be nowhere in the pennant race,” declared the Pittsburgh Press.51 He shut out the Cardinals and added two hits in a 14-0 laugher on September 3 to record his 20th victory. That also pushed the Bucs two games in front of the Cubs and Giants. Propelled by the league’s highest-scoring offense, the Pirates won 29 of their last 44 games to capture their second pennant in three years. In a remarkable season, Hill (22-11) paced the staff in victories and appearances (43), completed 22 of 31 starts, and posted a 3.24 ERA in 277⅔ innings, He anchored the staff’s quartet of productive starters, including Meadows (19-10), Kremer (19-8), and Vic Aldridge (15-10).

The Pirates were overwhelming underdogs to the New York Yankees (110-44) in the World Series. “I was very disappointed that I did not get to pitch one of the games in Pittsburgh,” recalled Hill, who started Game Four in the Bronx.52 He gave up singles to the first three batters he faced, culminating with Babe Ruth’s RBI, then struck out the next three batters to keep the game tied 1-1 after one inning. In the fifth, Hill surrendered a towering home run to The Babe to give the Yankees a 3-1 lead. Ruth’s blast was immortalized on a US commemorative stamp from 1983. Lifted for a pinch-hitter with the Pirates down 3-1 in the seventh, Hill yielded nine hits and three runs in his only postseason appearance. After the Pirates tied the game in the seventh, the Yankees completed the sweep when Earle Combs scored on Johnny Miljus’s wild pitch with two outs in the ninth, giving New York a 4-3 win.

The 1928 season was as disappointing for the Pirates as the previous season was exciting. Meadows was lost for almost the entire season. Aldridge was traded in the offseason, as was malcontent Kiki Cuyler, one of baseball’s most dynamic players. Cuyler had clashed with manager Donie Bush in ’27 and was benched. The Pirates struggled to play .500 ball for the first half of the season and finished in fourth, 9 games behind the Cardinals.

Hill’s season looked doomed from the time he arrived at spring training. Plagued once again by a “lame back,” he pitched sparingly in Paso Robles.53 He was back in Linesville to get his spine and arm adjusted by Greene days before the season commenced.54 After debuting in relief, Hill suffered a serious leg injury in his first start, on April 19. A shot from the Cardinals’ Jim Bottomley caromed off his leg, requiring “electrical baking treatment” (an early form of electrotherapy).55

Hill failed to duplicate his success from 1927. Plagued by inconsistencies and labeled one of the “pitching derelicts” on the staff, he suffered an eight-week slump through August 3, winning just two games with a 6.28 ERA.56 He turned his season around with a five-game winning streak, but by that time the Bucs were in fifth place. Hill’s season was curtailed by yet another injury, on September 24, when he was struck on the elbow by a liner by the Braves’ Heinie Mueller.57 Coincidentally, the Braves’ starter, Ben Cantwell, suffered a season-ending fractured right thumb on a drive by Adam Comorosky earlier in the game. In what proved to be his second and final full season as a starter in the majors, Hill posted a 16-10 record with a 3.53 ERA in 237 innings.

The grind of tossing almost 3,000 innings of professional baseball had taken its toll on the 33-year-old Hill. In 1929 he toiled through yet another injury-filled spring training. Wollen reported that Hill “was unable to hoist his left leg more than a foot off the ground without experiencing pain.”58 After two disastrous early-season starts, Hill was shunted to the bullpen, where he pitched primarily in long relief and mop-up situations. It was “no surprise,” declared the Pittsburgh Press, when he was released and subsequently sold to the Cardinals in a waiver transaction on August 28.59

Serving as batting-practice pitcher and making only three appearances for the Cardinals, Hill was involved in a brouhaha that extended into the offseason. According to his autobiographical booklet, he refused to pitch against the Pirates during their five-game series in St. Louis at the end of September because the club, which had already secured a second-place finish, had awarded him a full share of their World Series earnings.60 (Newspapers reported that Hill had not been asked to pitch.) In November, however, Commissioner Kenesaw Landis overruled the Pirates’ decision, enforcing a rule prohibiting teams from awarding bonuses to released players. It cost Hill approximately $1,000.61

Hill’s brief tenure with the Cardinals ended after four dismal early-season appearances in 1930. He was released to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, where he struggled in a spot starter’s role, posting a 6.05 ERA in 128 innings.

Transferred to the Rochester Red Wings for the 1931 season, the 35-year-old Hill experienced a renaissance despite suffering what seemed to be a season-ending injury in spring training. George Sisler fell on his right knee, causing it to buckle. Plagued by painful swelling the entire season, Hill still went 18-12 and helped manager Billy Southworth’s team to the International League title. Rochester went on to win the Junior World Series title by beating the St. Paul Saints of the American Association.

Hill donned three different uniforms in 1932, beginning with the Red Wings in spring training and then splitting the season between the American Association’s Columbus Red Birds and Minneapolis Millers. Limping through the season from the effects of his knee injury, Hill went 12-13, despite giving up 252 hits in 183 innings.

Hill’s professional career seemed to reach its conclusion with the Millers in 1933 when he injured his arm using a six-cable exerciser at spring training and was released.62 After playing semipro ball with the Indianapolis Kautskys in the Indiana-Ohio League that summer, Hill attempted a comeback in 1934. His former Pirates skipper Bill McKechnie invited him to the Boston Braves’ spring training in St. Petersburg, but Hill was released before camp ended.63

In parts of 10 big-league seasons, Hill went 49-33 with a 3.44 ERA in 787 innings. Though his minor-league statistics are not complete, he won at least 190 games (losing 149) and logged 2,763 innings in 14 seasons.

Hill had made his offseason home in Indianapolis since the mid-1920s. Divorced from Ruth in 1933, he married Jessie Mae Viles in 1940. She had worked as an officer and matron at the Indiana Girls School, a juvenile reformatory institution east of downtown Indianapolis. Hill worked as a safety inspector at the General Motors plant, retiring after 24 years at the age of 65 in 1960. As a retiring gift, GM sent Hill and his wife to Pittsburgh to see the Pirates play in their first World Series since 1927.64

In his brief autobiographical booklet, The Battles of Bunker Hill, Hill concludes his personal story in 1934 and does not mention anything about his life in the five decades since his retirement from baseball. SABR member Norman Macht interviewed Hill in the summer of 1985 and subsequently published the interview in his book They Played the Game (2019).65

Carmen Hill died at the age of 94 on January 1, 1990. He was cremated at the Flanner and Buchanan Fall Creek Mortuary. His remains were buried at the Crown Hill Cemetery, in Indianapolis, next to his wife, who had passed in 1978.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Special thanks go to SABR-member Daniel Shirley who loaned the author his personal copy of Hill’s short autobiography.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, newspapers via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Lou Wollen, “Carmen Hill Expects to Be Big Help to Pirates Next Season,” Pittsburgh Press, January 9, 1927: 28.

2 Carmen Hill, An Autobiography: The Battles of Bunker Hill (Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 1985), 4.

3 Hill, 3.

4 “Dooin Seeks Pitchers,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 12, 1914: 10.

5 Hill, 6.

6 “Carmen Hill Bought by Pirates,” Warren (Pennsylvania) Tribune, September 1, 1926: 1.

7 Hill, 7. Unfortunately Hill does not mention this family acquaintance by name in his autobiographical booklet. In a different version of the story, the unnamed lawyer contacted Pirates manager Fred Clarke, a friend, on whose recommendation Dreyfuss signed Hill. See Cullen Hill, “Carmen Hill, Pirates; Hurler, Farm Hand,” York (Pennsylvania) Record, January 9, 1928: 11.

8 Charles J. Doyle, “Pirates Leave for Dawson Springs Training Camp,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 7, 1915: 16.

9 Ralph S. Davis, “Dreyfuss Says the Pirates Pitching Staff Is High Class,” Pittsburgh Press, December 12, 1915: 23.

10 Lou Wollen, “Be-Spectacled Twirlers Are in Constant Danger,” Pittsburgh Press, March 22, 1927: 34.

11 Edward F. Balinger, “See Saw Conflict Won By Yanigans,” Pittsburgh Post, March 29, 1915: 9.

12 Pittsburgh Dispatch reprinted in “Brilliant Future Is in Store for Carmen Hill,” Warren (Pennsylvania) Western Times Mirror, April 2, 1915: 5.

13 Edward F. Balinger, “Pirates Blanked by Former Mates in Twelve Innings,” Pittsburgh Post, June 21, 1915: 9.

14 “Pirate Recruit Loses 19-Inning Mound Duel, Pitching for Steelmen,” Pittsburgh Post, June 28, 1915: 14.

15 Sportswriter Harry Keck predicted the events several weeks before they transpired, declaring “[Hill] seems to have the call on Vance,” Expo Games Feature This Week’s Program; other Timely Topics,” Pittsburgh Post, August 2, 1915: 18.

16 Charles J. Doyle, “Pirates Win Twice Though Hard Hitting,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 18, 1915: 10.

17 “Carmen Hill Has Learned by Experience to Study Batters Instead of Using Strength,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, February 15, 1931: 27.

18 Ralph S. Davis, “Dreyfuss Says the Pirates Pitching Staff Is High Class,” Pittsburgh Press, December 12, 1915: 23.

19 “Carmen Hill Has Learned by Experience to Study Batters Instead of Using Strength,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

20 Cullen Cain, “Carmen Hill, Pirates’ Hurler, Farm Hand,” York (Pennsylvania) Daily Record, January 9, 1928: 11.

21 Edward F. Balinger, “Another Pirate Goes to Minors,” Pittsburgh Post, January 7, 1917: 14.

22 “Killed at Union City,” Kane (Pennsylvania) Republican, October 16, 1916: 2.

23 Ralph S. Davis, “Carmen Hill Is Released,” Pittsburgh Press, January 7, 1917: 19.

24 Edward F. Balinger, “Birmingham Again Wallops the Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post, April 8, 1917: 18.

25 “No-Hit Game Is Pitched by Carmen Hill,” Pittsburgh Post, July 31, 1917: 8.

26 “Dreyfuss Closes Big Deal With Birmingham,” Pittsburgh Post, August 16, 1917: 8.

27 Hill, 8.

28 “Carmen Hill Is Injured in Practice,” Pittsburgh Post, March 20, 1918: 10.

29 Hill, 8.

30 “Hospital List Is Dwindling,” Pittsburgh Press, April 2, 1918: 22.

31 Hill, 10.

32 Hill, 10.

33 Bezdeks Held to Two Swats and Defeated,” Pittsburgh Post, July 29, 1918: 8.

34 Ed. F. Balinger, “Swap Brings New Backstop to Buccaneers,” Pittsburgh Post, March 22, 1919: 12.

35 John W. Head, “Pirates Sell Pitcher Hill to the Tribe,” Indianapolis Star, July 10, 1919: 12.

36 Lou Wollen, “Carmen Hill Expected to Be Big Help for Pirates Next, Season,” Pittsburgh Press, January 9, 1927: 28.

37 Hill, 10.

38 Hill, 11

39 Hill, 12.

40 “Five Persons Die in Auto Mishaps,” Indianapolis News, July 6, 1925: 17.

41 “Pirates Buy Carmen Hill from A.A. Club,” Pittsburgh Post, September 2, 1926:

42 “Pirates Players Go to Hoosiers Completing 1926 Bucco Exchange,” Pittsburgh Post, November 24, 1926: 13.

43 The Pirates were racked by a player insurrection. A trio of veteran players – Babe Adams, Carson Bigbee, and Max Carey – voiced their displeasure with club vice president and former skipper Fred Clarke’s presence on the dugout bench and what they considered meddling in the team’s affairs. This eventually became known as the ABC affair, and resulted in the release of all three players on August 13.

44 Charles J. Doyle, “Hill, Aided by Wright’s Timely Hitting, Hurls 10-Inning Triumph in Debut as Corsair,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 4, 1926: 4.

45 “Playing the Game with the Pirates,” Pittsburgh Press, September 4, 1926: 9.

46 Charles J. Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, June 3, 1927: 11.

47 Lou Wollen, “Playing the Game,” Pittsburgh Press, June 3, 1927: 46.

48 Hill, 18.

49 “Difficulties Fail to Stop Champs,” Pittsburgh Press, June 27, 1927: 26.

50 Hill, 15.

51 “Difficulties Fail to Stop Champs.”

52 Hill, 16.

53 Lou Wollen, “Bucs Boss Seeks Another Catcher,” Pittsburgh Press, April 2, 1928: 29.

54 “Carmen Hill Gets Treatment Sunday at Hands of Guy Greene,” Franklin (Pennsylvania) News-Herald, April 9, 1928: 9.

55 Edward F. Balinger, “Following the Bucs,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 23, 1928: 18.

56 “Pirate Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, July 21, 1928: 12.

57 Edward F. Balinger, “Pirates Capture First from Braves in Ten Innings, 3-1; Blankenship Is Beaten, 4-2,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 25, 1928: 16.

58 Lou Wollen, “Pirates’ High Pressure Spring Training Continues,” Pittsburgh Press, March 3, 1929: 39.

59 Lou Wollen, “Hill Is First to Be Released,” Pittsburgh Press, August 27, 1929: 28.

60 Hill, 18. See also, “Pirates Vote Series Share to Bush,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, September 30, 1929: 25.

61 “Former Pirate Pitcher ‘Out’ $1,000,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, November 8, 1929: 39. Hill received a double whammy. Under the impression that Hill would receive a full share from the Pirates, the fourth-place Cardinals did not award him anything. “Carmen Hill’s Case Holds Up Series Checks,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 8, 1929: 48.

62 Hill, 20.

63 United Press, “Carmen Hill Drills with Boston Braves,” Des Moines Register, March 6, 1934: 8.

64 Chester L. Smith, “There’s Difference Between Camp Talk and Actual Results,” Pittsburgh Press, September 25, 1960: Section 4, 2.

65 Norman Macht, They Played the Game. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

Full Name

Carmen Proctor Hill

Born

October 1, 1895 at Royalton, MN (USA)

Died

January 1, 1990 at Indianapolis, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.