Charles Zimmer

On August 6, 1890, Cy Young made his major-league debut with the Cleveland Spiders and hurled a three-hitter as the Spiders defeated Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts, 8-1. Young’s batterymate was Chief Zimmer. Young was accustomed to minor-league backstops who struggled to catch his blazing fastballs. When Zimmer had no trouble catching them, Young worried that he was not throwing hard enough.1 Years later, Young recalled his debut:

On August 6, 1890, Cy Young made his major-league debut with the Cleveland Spiders and hurled a three-hitter as the Spiders defeated Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts, 8-1. Young’s batterymate was Chief Zimmer. Young was accustomed to minor-league backstops who struggled to catch his blazing fastballs. When Zimmer had no trouble catching them, Young worried that he was not throwing hard enough.1 Years later, Young recalled his debut:

“The thing that stands out most vividly … was the fact that I crossed Chief Zimmer in a pinch, handing him a curve ball when he had called for a fast one. Zimmer got the ball squarely on his bare hand. Then he started for the box. I expected to get a good call-down. In fact, I wouldn’t have been surprised if Zimmer had started by swinging his right. Here I was, a green kid, pulling off a bonehead that might have laid up one of the league’s star catchers. I’ll remember my surprise to my dying day when Zimmer said: ‘Now, look here, young fellow, you must learn to watch my signs a little closer. I called for a fast one and you gave me a curve. A thing like that might have lost us the game. You’re just starting in. Now, please watch what I tell you to pitch, and if you’re bound to pitch something different, let me know about it. You’re doing finely. Just remember and it will help you win a lot of games you’d lose otherwise.’ Surprised, was I? Well, slightly. And I made up my mind right there that the finest man God had ever created was my catcher, Chief Zimmer.”2

Young and Zimmer formed one of the greatest batteries in baseball history. With Zimmer’s help, Young averaged 29 wins per season from 1891 to 1898. Since 1956, the Cy Young Award has been bestowed upon the best pitchers in baseball. What about the catchers who helped those pitchers? They deserve a Chief Zimmer Award.

Charles Louis Zimmer was born in Marietta, Ohio, on November 23, 1860. He was of German descent, the eldest child of John J. and Catharina (Fischer) Zimmer.3 Charles’s brother William was born in 1871. Sometime between 1870 and 1875, the family moved to Ironton, in southern Ohio, beside the Ohio River. John was a farmer and a carpenter.4 Catharina died in 1875, and John remarried before 1880.5

As a young man Charles Zimmer apprenticed in a cabinetmaker’s workshop.6 At age 22, he married 14-year-old Minnie Frowein, a pretty girl with dark eyes and a beautiful singing voice.7 The young couple had three daughters: Leona born in 1883, Edna in 1885, and Galatea in 1886.8

After playing on amateur baseball teams for several years, Zimmer joined a professional team in Ironton in 1884. He played well enough to attract the attention of the Detroit Wolverines, who were in last place in the National League. Zimmer made his major-league debut with Detroit on July 18, 1884. In an eight-game tryout with the team, he performed poorly: 2-for-29 at the plate with 14 strikeouts, along with 8 fielding errors and 11 passed balls. Zimmer gave up on professional baseball and moved his family to Chicago, where he started a laundry business.9

In 1886 Zimmer gave professional baseball another try. He joined the Poughkeepsie (New York) team of the Hudson River League. As the team’s star catcher, he batted .409 in 43 games.10 The team was called the Indians by reporters, and since Zimmer was the captain of the squad, he was nicknamed Chief.11 After the Indians’ season ended, Zimmer was given a six-game trial with the New York Metropolitans, but he failed to impress.

Zimmer batted .331 in 64 games for the 1887 Rochester (New York) Maroons12 and was acquired by the Cleveland Blues. He batted .231 in 14 games for the Blues in 1887, and .241 in 65 games in 1888. More importantly, he was an understudy to one of the greatest defensive catchers of the 19th century, Charles “Pop” Snyder. In 1889 the Cleveland Blues became the Cleveland Spiders, and Zimmer became the team’s primary catcher, replacing the aging Snyder. Zimmer batted .259 in 84 games, and he hit his first major-league home run on September 9, 1889, off Tim Keefe of the New York Giants.

Zimmer was big – 6-feet, 190 pounds – and strong. He was an impressively sturdy catcher, with big hands. Unlike most ballplayers, he abstained from alcohol and tobacco, and did not swear. He spoke in a calm, deep voice and conducted himself with a gentlemanly deportment both on and off the field. Zimmer was a natural leader, popular with teammates and fans, and a devoted family man. The Zimmer family resided in a Cleveland home that was filled with attractive furniture he had made.13

After the 1889 season, many major leaguers joined a union known as the Brotherhood, which established the Players League in 1890 to rival the established National League.14 In December 1889 Zimmer joined the Brotherhood and agreed to play for the Cleveland team in the Players League. However, two weeks later he left the union and signed a three-year contract with the Cleveland Spiders of the National League.15

In 1890 Zimmer set records for most games played by a catcher in one season (125) and most consecutive games caught in one season (110).16 He caught every game from the season opener on April 19 through September 2.17 The streak would have continued, but he left the team to attend to his wife, who had been stricken with typhoid.18 Zimmer batted only .214 in 1890, but his durability behind the plate was astounding. Other catchers were upset with him and concerned that their managers would expect the same endurance from them.19 Zimmer was reportedly the first major leaguer to use the large catcher’s mitt invented by Arthur Irwin; without it, Zimmer’s feat was deemed impossible.20 Zimmer regularly had his hands massaged to reduce swelling and soreness.21

Zimmer led NL catchers with 116 games played in 1891 and improved his batting average to .255. On May 6 his agility behind the plate impressed the Chicago Tribune. Cleveland pitcher Henry Gruber was on the mound.

“Zimmer had a busy day behind the bat handling the erratic pitching of his twirler. Gruber has a peculiar squirm in the box. … When he makes up his mind to let go of the ball, it is just as apt to go behind the batter as across the plate. Zimmer makes no pretensions of acrobatic ability, but some of his feats yesterday were worthy of a star performer in the ‘greatest show on earth.’”22

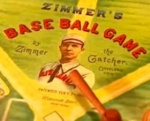

In November 1891 Zimmer invented a clever tabletop game, which he called “Zimmer’s Base Ball Game.”23 He is pictured prominently in the infield of the game board. A ball is “pitched” from a spring-action device toward home plate, where a bat is flipped to hit the ball. Pegs in the infield and outfield represent the fielders. The board is adorned with color portraits of baseball stars, including Cy Young, Buck Ewing, and Ed Delahanty.24 One of the players pictured is Zimmer’s brother William, a minor league catcher.25

In November 1891 Zimmer invented a clever tabletop game, which he called “Zimmer’s Base Ball Game.”23 He is pictured prominently in the infield of the game board. A ball is “pitched” from a spring-action device toward home plate, where a bat is flipped to hit the ball. Pegs in the infield and outfield represent the fielders. The board is adorned with color portraits of baseball stars, including Cy Young, Buck Ewing, and Ed Delahanty.24 One of the players pictured is Zimmer’s brother William, a minor league catcher.25

The game was a success and thousands of units were sold in the 1890s.26 In 1946 journalist E.V. Durling wrote: “I still think the best baseball game toy was the one invented by Chief Zimmer years ago. Often wonder why it isn’t on the market now. I had one when [I was] a kid. I certainly had a tough time getting it away from my father and uncle who played with it by the hour.”27 Today fewer than 10 examples of the game are known to exist. One in top condition sold at auction in 2008 for $19,975.28 Mark Cooper, in his illustrated guide to baseball games, calls the Zimmer game “the Mona Lisa of all baseball games … the most valuable, beautiful, and desired game.”29 Zimmer was quite an entrepreneur. The Zimmer catching glove was sold in large quantities in 1892.30

Although the Cleveland Spiders already had Zimmer under contract for the 1892 season (the third year of his three-year contract), the team owners sent him a new contract to sign before the season. It contained new clauses favorable to the team owners, including a “reserve” clause that stipulated that Zimmer could play only for the Spiders in 1893. As a businessman, Zimmer understood contracts. Why should he sign the new contract when he already had a more favorable contract to play for Cleveland in 1892? He signed the new contract, but only after lining out the objectionable clauses.31

Davis Hawley, the Cleveland team secretary, said, “Zimmer will sign a contract just as we want or he will not play ball next season. If we waived the reservation clause on him, we would have to do it with others, and that we don’t propose to do.”32 Sporting Life said Zimmer was making “an unreasonable kick”: “All cannot be paid the same salaries, but all should sign the same form of contract. There must be no exemption or favorite-playing if satisfaction and harmony is to be as prevalent among players as it now is among club owners.”33 Finally, under duress, Zimmer signed the new contract without modification.

Despite undergoing knee surgery after the 1891 season,34 Zimmer, the iron man from Ironton, caught 111 games in 1892 and batted .264. The Spiders acquired another fine catcher, “Rowdy Jack” O’Connor, to serve as Zimmer’s backup. O’Connor was jealous of Zimmer’s leading role. Umpire Tim Hurst told this story about them:

“Jack O’Connor’s temper had been aroused by an article in a Pittsburgh paper, in which Zimmer was spoken of as the Cleveland team’s star catcher. Chief, holding a big bat in his hands, was sitting at one end of the bench; O’Connor, empty-handed, at the other. Suddenly I heard O’Connor say to Zimmer: ‘If you didn’t have that stick in your hand I’d knock your head off.’ Like a flash, [Cleveland shortstop] Ed McKean darted over and yanked the bat from Chief’s paws. ‘He hasn’t got the stick in his hands now, Jack,’ said the big shortstop. ‘Go ahead and knock his head off – if you can.’ … Rowdy Jack started to get up, settled back on the bench and began to cry like a child. A little later he and Chief were shaking hands, and the prospective fight ended in the establishment of a friendship that has never since been disturbed.”35

Zimmer batted .308 in 57 games in 1893. He missed seven weeks of the season after he broke his collarbone on July 12, when he ran to first base and collided with Tom Tucker, the Boston first baseman.36 Tucker deliberately blocked Zimmer from reaching the base, an example of the “dirty play” that was common during that era.

From 1894 to 1897, Zimmer excelled on offense and defense. He hit .303 over that period, including a career-high .340 in 1895, and each year he ranked either first or second in the league in fielding percentage by a catcher. He had six hits in one game off Win Mercer of the Washington Senators on July 11, 1894.37 In the first game of a doubleheader on June 17, 1895, Zimmer hit two singles, a solo homer, and a grand slam off Kid Nichols of the Boston Beaneaters.38 “There is no ball player in the country who can hit a ball harder than Zimmer,” said Sporting Life in 1895.39 Behind the plate, Zimmer “tosses the ball down to second quicker and with apparently less effort than any backstop in the League.”40 In 1894 he led NL catchers with 51 percent caught stealing. Zimmer helped the Spiders defeat the Baltimore Orioles, 4 games to 1, in the 1895 Temple Cup championship series.

In the offseason, Zimmer played amateur indoor baseball and worked as a salesman in the men’s clothing department at the E.R. Hull & Dutton store in Cleveland.41 After the 1897 season, he opened a cigar store that became a popular hangout for ballplayers and fans.42 Since Zimmer did not smoke, a cigar store seems to be an odd choice of business. The Chief had a wry sense of humor; perhaps he saw himself as the cigar store Indian.

Troubled by a sore arm,43 Zimmer played in only 20 games during the 1898 season. He rebounded in 1899 by batting .307 in 95 games and leading NL catchers with his career-high .978 fielding percentage. In 1899 Frank Robison owned two NL teams, the Cleveland Spiders and the St. Louis Perfectos, and transferred the best players on the Spiders to the Perfectos. Zimmer was photographed with the Perfectos in the spring of 1899,44 but never played for the team, as Robison honored his request to remain in Cleveland.45 However, Zimmer was assigned to the Louisville Colonels in June 1899 against his wishes,46 and in December 1899 he was sent to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

The 1900 Pirates were a talented club, featuring the great Honus Wagner. The balding, 39-year-old Zimmer was the oldest man in the league but showed no signs of slowing down, as he batted .295 in 82 games for his new team. He was the “right hand man” of Pirates player-manager Fred Clarke.47

In July 1900 the Protective Association of Professional Base Ball Players was formed, and Zimmer was elected president of this new union.48 Because Zimmer did not support the Brotherhood in 1890, his election was criticized by some.49 However, according to the Washington Hatchet: “It is the general opinion that the players have been wise in their selection of officers. Charles Zimmer is one of the veteran and brainy men of the profession. He has the confidence of the club owners and respect of the players.”50 Attorney Harry Taylor was hired to represent the union.

In December 1900 Taylor presented a list of union demands to National League magnates, who quickly rejected all of them.51 Beaneaters owner Arthur H. Soden said, “The players made a mistake in having a lawyer. Had the boys come to the meeting and made reasonable demands they would have received due consideration.”52

Ban Johnson, president of the American League, accepted the union demands, to lure NL players to his league.53 Facing pressure from the rival American League, NL club owners met with Zimmer in February 1901. In what became known as the Zimmer Agreement, the NL magnates agreed to abolish the farming, buying, and selling of a player without the player’s consent; and to limit the reserve option so that a player could be reserved for only one year after the first year of a contract and become a free agent after the second year.54

Sporting Life praised Zimmer for his “skill and shrewdness” in negotiating the agreement.55 The NL players were pleased with the agreement, because they improved their lot without having to make a risky leap to the upstart American League. The AL players were displeased with the agreement; they saw themselves as revolutionaries against an unjust regime, and this peace agreement made it harder to promote their cause. Ban Johnson was outraged. He said, “So long as Zimmer is at the head of the Players’ Protective Association I shall refuse to have any dealings with the order. He has proved himself one of the worst characters in baseball by his double dealing, and I cannot recognize any order of which he is the head.”56 Zimmer already had numerous concessions from Johnson; that Zimmer also obtained concessions from the entrenched NL magnates was remarkable. Zimmer helped players in both leagues.

Zimmer resigned as president of the fractious union in June 1901, and the union dissolved in July 1902.57 With no union representing the ballplayers, magnates of both leagues soon abrogated the progress Zimmer had made.

In early August 1901, Zimmer was sidelined after he was deliberately spiked by his former teammate Jesse Burkett.58 In late August, Zimmer slipped and fell when getting out of a train berth and broke a rib.59 He batted .220 in 69 games during the 1901 season, and the Pirates won the NL pennant. In the offseason Zimmer tended to his many business interests in Cleveland, including real estate, “a large cigar factory,” a bowling alley, a billiard room, slot machines, and “a laundry office.”60

Zimmer played little in May and June 1902, so that he could be near his ill wife in Cleveland.61 On August 19, 1902, the Pirates defeated the New York Giants, 5-4. In the seventh inning, the 41-year-old Zimmer made an impressive catch of a foul popup against the grandstand; “(T)he old man is still very active,” said the Pittsburg Post.62 In the same game, Pirates second baseman Claude Ritchey was spiked by a baserunner. “The game was delayed for some time until Ritchey’s foot was examined. Chief Zimmer made the announcement that Claude had lost a toe, but would play with four, if the rules allowed.”63

In a 7-4 Pittsburgh victory over St. Louis on September 20, 1902, Zimmer tallied five assists. His throwing was “one of the features of the game,” reported the Pittsburg Post. “The old man put them down to second with apparent ease.”64 Years later, Honus Wagner said, “The man who is not a baseball player probably does not know that some players throw what is known as a heavy ball. It drops in the glove like a ton of lead.” Zimmer “threw the lightest ball to second I ever handled,” he said. “You could catch it without a glove.”65 Zimmer batted .268 in 42 games in 1902, and the Pirates again won the NL pennant.

In 1903 Zimmer was the playing manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss “loaned” Zimmer to the Phillies, to help keep the Philadelphia team financially afloat. It was Zimmer’s final major-league season, and it was a difficult one. He batted .220 in 37 games and guided the weak Phillies to a disappointing seventh-place finish. During the second game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia on August 8, 1903, a portion of the left-field bleachers collapsed, causing spectators to plunge to the ground. The accident killed 12 people and injured 232.66

The Phillies chose not to rehire Zimmer for the 1904 season. He went to spring training with the Pirates in March 1904, hoping to rejoin the club,67 but the Pirates did not sign him, so he instead became a National League umpire. Comfortable behind the plate, Zimmer was outstanding at calling balls and strikes.68 New York Giants pitcher Joe McGinnity praised his work: Zimmer “is the best umpire in the business for pitchers today, for he stands behind the catcher with his eyes open and sees every curve or sudden shoot that the ball takes. It is a pleasure to work with such an umpire.”69 The Pittsburgh Press liked Zimmer’s cool head:

“The fact that Chief Zimmer allowed several of the New York players to register vigorous protests … caused some fans to wonder why the umpire did not take advantage of his authority and put these men out of the game. … The Chief has not forgotten the days when he was worked up to a pitch bordering almost on frenzy whenever bad decisions were rendered. … He makes allowances for the tempers of players, and does not send them to the woods, except when they become too personal in their remarks. He is a mild-mannered old gentleman, slow to wrath and easily forgiving.”70

Despite Zimmer’s good work in 1904, the National League did not rehire him for the 1905 season. He umpired in the Eastern League in 1905, and in the Southern Association in 1907. In 1906 he was the player-manager, and part owner, of the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association. Zimmer retired from professional baseball on July 13, 1907, at the age of 46.71

In August 1907 Zimmer picked his all-time all-star team: John Clarkson, pitcher; Charlie Bennett, catcher; Charlie Comiskey, first base; Fred Pfeffer, second base; Billy Nash, third base; Jack Glasscock, shortstop; Tip O’Neill, left field; Ned Hanlon, center field; and Sam Thompson, right field.72 Zimmer included only 19th-century stars on his team. He felt the 20th-century game was inferior, due to an influx of “half-ripe players.”73 With the advent of the American League, there were 16 major-league teams and not enough talent to fill them. Many years later, Zimmer would say that Ty Cobb was the greatest of all time. Cobb “was so good he was a freak,” said Zimmer.74

Scoring in major-league baseball dropped to an all-time low in 1907. Zimmer explained one reason for the decline:

“When I first became a professional player, a fielder had to get the ball squarely in his hands in order to catch it as he had no glove with a big pocket to do the work for him. The hard drives often went safe because they were too hot to handle. Now, all a player has to do is get his gloved hand on the ball and he can either catch it or knock it down and throw out the runner. Dozens of long liners and long flies go to the outfield and are caught with one hand where in the old days they would have gone for two- or three-base hits and often for home runs. All that works against the batsman.”75

Zimmer suggested some interesting ways to increase scoring:

- Do not move the bases, but move the foul lines to increase the amount of fair territory. The foul lines would commence at home plate as they currently do, but the first-base line would pass six feet to the right of first base, and the third-base line would pass six feet to the left of third base. With this arrangement, many more balls would be fair and become extra-base hits. With more ground for the outfielders to cover, more balls would drop in safely.76

- In his retirement, Zimmer regularly attended major-league games and faithfully rooted for the Cleveland Naps and Cleveland Indians.77 He said: “It’s not right for a pitcher to take away [Nap] Lajoie’s chance of hitting by walking him when there are men on bases. … Now, if the rules committee would pass a law allowing the base runners to advance a base every time a batsman was walked, regardless of whether he was forced, there wouldn’t be so many intentional passes. Pitchers would have to put the ball over and the good batters would get a chance to do what they are paid for.”78

In July 1921, as part of the 125th celebration of the founding of Cleveland, 54-year-old Cy Young and 60-year-old Chief Zimmer were the starting battery and played two innings of an old-timer’s game to the delight of a large crowd.79 “A quarter of a century seemed to make no difference. They worked together … as if they had been playing continuously until now.”80 Young and Zimmer were the best of friends and visited each other often.

In 1932, the 71-year-old Zimmer said, “Not a thing wrong with me. I work in my garden every day, stay up as late as I like, eat what I like and run around like a youngster.”81 The multi-faceted Zimmer – catcher, manager, umpire, union leader, businessman, furniture maker, and gardener – died in Cleveland on August 22, 1949, at the age of 88.

Notes

1 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 4, 1922.

2 Washington Herald, July 30, 1911.

3 Ancestry.com.

4 1880 US Census; Sporting Life, November 29, 1902.

5 Ancestry.com.

6 Sporting Life, August 16, 1890.

7 Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 2, 1895; Sporting Life, April 30, 1904.

8 1900 US Census; Ancestry.com.

9 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 4, 1922.

10 Sporting Life, August 4, 1886; The Sporting News, January 12, 1949.

11 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 30, 1932.

12 The Sporting News, January 12, 1949.

13 Sporting Life, August 16, 1890.

14 The Players League lasted only one season.

15 Chicago Inter Ocean, December 6, 1889; Pittsburg Dispatch, December 20, 1889.

16 Sporting Life, September 6 and October 11, 1890.

17 Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 5, 1890.

18 Sporting Life, September 13, 1890.

19 Sporting Life, February 7, 1891.

20 Winnipeg (Manitoba) Tribune, October 5, 1912; Edenton (North Carolina) Fisherman and Farmer, September 19, 1890. Some catchers of that era padded their skimpy gloves with beefsteaks to protect their hands.

21 Sporting Life, October 8, 1892.

22 Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1891. On May 6, 1891, the Chicago Colts defeated the Cleveland Spiders, 12-4.

23 Sporting Life, November 28, 1891.

24 Mark Cooper, Baseball Games: Home Versions of the National Pastime, 1860s-1960s (Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer, 1995).

25 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent, February 27, 1896.

26 Cincinnati Enquirer, November 18, 1893.

27 Tucson (Arizona) Daily Citizen, December 11, 1946.

28 robertedwardauctions.com/auction/2008/1181.html.

29 Cooper, Baseball Games.

30 Sporting Life, April 9, 1892; Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 24, 1892.

31 Chicago Inter Ocean, January 10, 1892.

32 Ibid.

33 Sporting Life, January 16, 1892.

34 Sporting Life, October 3, 1891.

35 Sporting Life, April 7, 1906.

36 Sporting Life, July 22 and September 23, 1893.

37 Sporting Life, July 21, 1894.

38 Boston Post, June 18, 1895.

39 Sporting Life, May 18, 1895.

40 Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, September 8, 1894.

41 Sporting Life, March 7, 1896; Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 18, 1894.

42 Sporting Life, December 25, 1897, and July 30, 1898.

43 Sporting Life, August 13, 1898.

44 Rich Blevins, Ed McKean: Slugging Shortstop of the Cleveland Spiders (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014).

45 Sporting Life, March 11, 1899.

46 Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 13, 1899.

47 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 22, 1900.

48 Allentown (Pennsylvania) Leader, July 16, 1900.

49 Sporting Life, August 25, 1900.

50 Washington Hatchet, September 16, 1900.

51 Boston Globe, December 13, 1900.

52 Boston Globe, December 16, 1900.

53 Indianapolis News, December 29, 1900.

54 Sporting Life, March 2 and 16, 1901.

55 Sporting Life, March 9, 1901.

56 Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, May 11, 1901.

57 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, June 24, 1901; Sporting Life, August 2, 1902.

58 Pittsburgh Press, August 2, 1901.

59 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 29, 1901.

60 Sporting Life, October 27, 1900; Boston Post, July 13, 1902.

61 Sporting Life, June 21 and 28, 1902.

62 Pittsburg Post, August 20, 1902.

63 Ibid.

64 Pittsburg Post, September 21, 1902.

65 Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal, January 16, 1924.

66 Tyler Kepner, The Phillies Experience: A Year-by-Year Chronicle of the Philadelphia Phillies (Minneapolis: MVP Books, 2013).

67 Sporting Life, April 16, 1904.

68 Indianapolis News, May 18, 1904.

69 Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Daily Northwestern, May 25, 1904.

70 Pittsburgh Press, September 2, 1904.

71 Atlanta Constitution, July 14, 1907.

72 Sporting Life, August 31, 1907.

73 Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 27, 1904.

74 The Sporting News, January 12, 1949.

75 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 9, 1908.

76 Pittsburgh Press, January 5, 1905.

77 Washington Times, July 31, 1912.

78 Pittsburgh Press, November 5, 1909.

79 Springfield (Missouri) Republican, July 30, 1921.

80 Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, July 30, 1921.

81 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 30, 1932.

Full Name

Charles Louis Zimmer

Born

November 23, 1860 at Marietta, OH (USA)

Died

August 22, 1949 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.