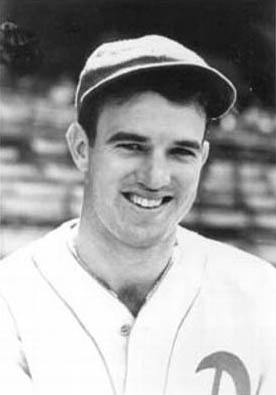

Chubby Dean

During the winter of 1935-1936 Connie Mack completed the destruction of his last winning dynasty. Since capturing his third straight pennant in 1931, Mack had traded or sold six of his regular position players and his top three pitchers to raise the cash he needed to keep his Philadelphia Athletics afloat during the Depression. The last of his stars, Jimmie Foxx, went to Boston during that winter along with three others for four Red Sox and $350,000 (in two transactions).1

During the winter of 1935-1936 Connie Mack completed the destruction of his last winning dynasty. Since capturing his third straight pennant in 1931, Mack had traded or sold six of his regular position players and his top three pitchers to raise the cash he needed to keep his Philadelphia Athletics afloat during the Depression. The last of his stars, Jimmie Foxx, went to Boston during that winter along with three others for four Red Sox and $350,000 (in two transactions).1

When spring training opened in 1936, the club had so many new faces that Mack’s son and assistant manager, Earle, carried a cheat sheet to match the players with uniform numbers. One of those unknown faces belonged to Lovill Dean, the youngest of several candidates to replace Foxx at first base. Dean was thought to be 19, though he was actually a year older, and didn’t mind answering to his high school nickname, “Chubby.”

He was no Jimmie Foxx. Eventually Mack decided he was no first baseman, either, and converted him to pitching. During his five-plus years with Philadelphia, Dean enjoyed his only consistent success as a pinch-hitter, batting .299 (40-for-134) in that role. The free-spirited left-hander sometimes exasperated the Grand Old Man. Although he was cheerful, likeable, and handsome, his conduct earned him the label “Mack’s bad boy.”2

Dean was a product of the Athletics’ Duke pipeline. Mack’s former pitching ace Jack Coombs coached at the university and sent a parade of players to Philadelphia (while Mack sent his youngest son to Duke). Mack’s preference for college boys dated back to the earliest years of the century with Columbia’s Eddie Collins and Jack Barry of Holy Cross. He helped pay the school expenses of some Duke players, including Dean. Although they had no written contract requiring them to sign with the Athletics, several did.3 The Duke connection, along with contributions from other former Mack players in the college coaching ranks (Barry at Holy Cross and Chick Galloway at Presbyterian), became a vital source of talent for the Athletics, because Mack lagged behind other clubs in building a farm system.

Alfred Lovill Dean came from Mount Airy, North Carolina, supposedly the model for native son Andy Griffith’s fictional Mayberry. Lovill was born on August 24, 1915, to Anna (Short) and Robert Gaston Dean, who owned a butcher shop. He was sometimes reported to be a cousin of Dizzy Dean, but he said they weren’t related.

He attended Oak Ridge Military Academy in North Carolina, where the pitcher Wes Ferrell had gone and followed his older brother Dayton to Duke. As a freshman he played basketball as well as baseball, winning five games on the mound with a no-hitter. But he had enough of school and wrote to Connie Mack midway through his sophomore year, asking to sign a contract.

Even though the Yankees had shown interest, the kid was savvy enough to see that he had a better chance to make the depleted Athletics roster. He did insist on one condition: He would be a hitter, not a pitcher, because he had hurt his arm pitching. Since he had hit around .450 for Duke’s freshman team, Mack agreed.

His skills with the glove didn’t impress anyone. He was blocky—5-feet-11 and 190 pounds by his own estimation—and had to fight to keep his weight down. He was not graceful or quick, but he could make contact at the plate. “The boy looks like a fine hitter,” Mack commented. “Only time will tell whether he will make a great first baseman.”4 Coming off a last-place finish, the A’s had no hope of contending for the pennant— “I expect to take an awful beating,” Mack said.5 He could afford to keep the minimum-wage rookie (who was paid $2,750) as a pinch-hitter while he tried to learn to play the field.

After the Athletics lost their first five games of 1936, they fell behind the Yankees, 11-7, in game six. They rallied in the seventh inning, plating four runs to tie the score. With two out in bottom of the ninth and the bases loaded, Mack called on Dean to pinch-hit. It was a high-pressure spot for a rookie, but Mack had little talent on his bench to choose from. The left-handed batter took two quick strikes from the Yanks’ Bump Hadley, then two balls, before he sliced a drive down the left-field line that fell in for a game-winning RBI single. Nobody called it a walk-off back then. For the Athletics, it was a welcome win, their first of the season.

By midseason, Dean had gone 12-for-30 as a pinch-hitter (.400) but had played only 10 innings in the field. A’s fans and Philly sportswriters were asking why “the pinch-hitting wonder” wasn’t playing every day.6 The handsome, smiling young man had already won a following among the Athletics’ faithful as one of the few bright spots in another dreary losing season. On July 11, with the club permanently buried in seventh place, Mack stirred his lineup, sending left fielder Bob Johnson to second base, first baseman Lou Finney to left, and Dean to first.

The veteran writer Jimmy Isaminger was not impressed with Dean’s work in the field. “Ground balls puzzle him,” Isaminger wrote after watching him for a couple of weeks. “He goes after ground balls that he should let go to the second baseman for first base is left uncovered…. His footwork at the bag is not yet good and he has trouble picking fouls out of the sun.”7 But Mack stuck with his prospect for 74 games in the rest of the season.

Dean delivered a .287 batting average in 375 plate appearances while showing little power or patience at the plate. He managed only one home run and 25 extra-base hits. His .711 OPS fell far short of the league average of .784 in the high-scoring American League.

Mack kept him in the lineup in 1937 as the regular first baseman for 78 games and saw Dean’s batting average fall to .262 with a .703 OPS. In addition to his defensive struggles, he lacked the power expected of a first baseman. The only sign of progress was his excellent bat-to-ball skills: he struck out just 10 times in 358 plate appearances.

By August the manager declared the experiment a failure. He ordered Dean to begin working out on the mound with coach Cy Perkins, a former catcher. After he pitched in two exhibition games, Dean made his regular-season debut mopping up in a game that was already lost. He “stopped the Browns dead” with three shutout innings. His first 13 pitches were strikes and he retired nine of 13 batters faced.8

Earle Mack was managing the A’s in September because his father was ill. He sent Dean out for his first start on September 19 as a sacrificial lamb against Cleveland’s 18-year-old wonderboy, Bobby Feller. Dean outpitched Feller for six innings, allowing two hits and one run, but he blew up in the seventh. The first four Cleveland batters reached base, and two of them scored before he got anyone out. After reliever Edgar Smith allowed one of the inherited runners to score, the Athletics hung on to give the left-handed neophyte his first victory.

Dean was scheduled for one more start, but his season ended early when he batted against Washington for his former Duke teammate Ace Parker. He grounded to second base, and Jimmy Bloodworth’s throw hit him in the head. He was sent home with a concussion.

Dean reported for spring training in Mexico City in 1938 with the pitchers and catchers. He quit first base cold turkey. For the rest of his career, he played there in parts of only two games. But his conversion was interrupted by an injury to the middle finger on his pitching hand that became infected. When the season opened, he was able to pinch-hit a few times but missed most of April and May. He didn’t pitch until June 5 and was shut down for good a month later.

Healthy in 1939, Dean earned his money in his first year as a full-time pitcher. He became the Athletics’ No. 1 reliever, working in 54 games, second most in the league, with a 5-8 record, and was credited retroactively with seven saves. He also had his best year at bat, hitting .351 with an .814 OPS, including 11-for-35 (.314) as a pinch-hitter, delivering 13 RBIs on those 11 hits. But he walked 80 in 116 2/3 innings and was smoked for a 5.25 ERA. The club’s defense, worst in the league, was little help. Columnist Cy Peterman wrote that Dean “isn’t a speedster, a curve fancier or a trick delivery man.”9 Without overpowering stuff, he needed to rely on control, and he didn’t always have it, walking more than four batters per nine innings in most seasons.

On July 23, 1939, the Tigers were blowing out Philadelphia 15-3 when Dean came on to pitch the final inning.

Rookie catcher Harry O’Neill, less than two months out of Gettysburg College, entered the game with him. Dean gave up another run in a game soon forgotten by everyone except O’Neill and his family. It was his only major-league inning. Marine Corps First Lieutenant Harry O’Neill was killed in action on Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945, one of two former big leaguers who lost their lives in World War II.

Despite Dean’s lackluster record, Mack thought he was improving. “Chubby seems to have an idea with pitching,” the old man said. “He thinks about every pitch he makes.”10 He had been agitating for a starting job, so Mack gave him a couple of chances during spring training in 1940 and was encouraged by the results. Dean’s reward was an assignment as the Athletics’ Opening Day starter against the Yankees, winners of four straight World Series. Mack’s decision was more than just a wild hunch; the Yankee lineup, with Joe DiMaggio hurt, had four left-handed hitters in a row—Red Rolfe, George Selkirk, Charlie Keller, and Bill Dickey—and another, Tom Henrich, lower down.

Dean held the champs to four hits through nine innings, and their only run was unearned, scored without benefit of a hit on a walk, an error, a sacrifice bunt, and a fly ball (a sac fly under today’s rules). But the Yankees’ Red Ruffing also allowed just a single run through nine. In the top of the 10th, Dean gave up two more hits and a walk, but escaped with no damage. In the bottom half the Athletics loaded the bases, and Dean knocked in the winning run with a fly ball. The victory was the first complete game of his career.

A week later he shut out the Yanks on four hits. But the Athletics soon began sliding downhill, heading for 100 losses and a last-place finish, and Dean slid with them. In a horrendous June, he gave up 32 runs in 28 innings. Mack thought his early success went to his stomach: “[he] got fatter every time I looked at him.”11 Sportswriter (and former A’s pitcher) Stan Baumgartner observed, “[S]oon he was out of shape, out of sight and almost out of the league.”12

After a bad outing in August, Dean left the team. “I suppose he was disgusted by the way he has been pitching,” Mack remarked.13 When he returned a week later, Mack declined to discipline him, but Dean’s pitching only got more disgusting. He finished his season with the two worst starts of his career, allowing 13 runs (11 earned) to Detroit and 16 (14 earned) to Boston. He went the distance in both games; was Mack punishing him?

Dean wound up with a 6-13 record and a bloated 6.61 ERA in 19 starts and 11 relief appearances. Opposing batters tattooed him for an .887 OPS. His pinch-hitting—9-for-27 (.333)—may have saved his job.

Dean’s roommate that year was another Duke product, rookie infielder Crash Davis. “He was a good-looking man,” Davis remembered, “and on my first road trip Chubby had too many women. He wasn’t married so the women were after him.”14 After the season Dean took himself off the market. The 25-year-old married Jean Carlotta Edinger, a TWA “air hostess” from New Jersey. Mack expressed hope that marriage would improve the pitcher’s focus: “If he doesn’t straighten himself up now and become a winning pitcher, he never will.”15

He was again the Opening Day starter against the Yankees in 1941 and shut them out until the ninth inning in a 3-1 victory. But he was pummeled in his next two starts. On April 29 the A’s and Indians were tied 3-3 in the seventh when Dean fell apart. A walk, an error, and an intentional walk filled the bases, and the next three Cleveland batters singled to bring home four runs.

Two days later Dean failed to show up for a game in Cleveland, just as he had vanished the previous year. Mack announced that he was suspended indefinitely.16 This time the suspension lasted 10 days.

After five years of coddling Dean, waiting for him to mature and prove his worth as a first baseman or a pitcher, Connie Mack was finally fed up. “Chubby was one of the game’s great eccentrics and one of the few men I’ve ever known who could make Mack visibly angry,” A’s pitcher Phil Marchildon wrote.17 Mack sold him to Cleveland for the $7,500 waiver price.

The Indians had lost their veteran starter Mel Harder to an elbow injury as they were fighting to hang onto second place. Dean went straight into the starting rotation and compiled a 4.39 ERA and a 1-4 record in eight games.

When Cleveland ace Bob Feller enlisted in the Navy after Pearl Harbor, Dean bid for his spot in the rotation in 1942. The Indians also lost first baseman Hal Trosky, who sat out the season because of chronic migraine headaches. Dean was rumored to be candidate for that job, but he put a stop to such talk, declaring “I’m a pitcher.”18 Manager Lou Boudreau seemed to have forgotten that; Dean pitched only once in the first four weeks of the season. On May 13 he got the call to start against the first-place Yankees, who led Cleveland by only a game and a half. He held them to six hits, but two of them were solo homers by Joe DiMaggio. Dean got those two runs back with an RBI double of his own and beat New York, 7-2, to lift the Indians within a half-game of the lead.

That won him a place in the rotation. Five days later he beat Philadelphia, 7-4, despite nine walks, to lift the Tribe into a first-place tie. By midseason his record stood at 6-2, and Cleveland writer Gordon Cobbledick called him “the No. 1 southpaw” in the American League.19 Although he faltered in the second half, Dean turned in the best season of his career: a 3.81 ERA in 27 games with an 8-11 record in 22 starts and 172 2/3 innings, both career highs.

But the next year he fell out of favor with manager Boudreau and pitched only 17 times with a 4.50 ERA and 5-5 record. Dean may have been preoccupied because he was expecting to be drafted into the military at any moment.20 He also lost his touch as a pinch-hitter, going 6-for-54 (.111) in his two-plus seasons with the Indians. So, when Dean was called into the Army Air Forces in October 1943, the consensus was that the club wouldn’t miss him that much.

Dean’s primary wartime duty was playing ball. After assignment to Daniel Field, Georgia, he went to the Pacific with a major league all-star team and toured island bases entertaining the troops.

He was 30 when he rejoined the Indians in 1946. Amid a glut of returning servicemen, the club released him during spring training. He had a three-game tryout with Triple-A Minneapolis but ended up with his hometown Mount Airy team in the Class-D Blue Ridge League. He was player-manager in 1947 and a minor-league umpire in 1955 before leaving professional ball for good.

In 1949 Dean sued the Indians under the Selective Service Act for $4,450 in back pay. The law required employers to allow servicemen to return to their old civilian jobs for one year, but the club had released Dean after less than a month. Several other players had collected in similar lawsuits, and Cleveland business manager Rudie Schaffer said the club expected to settle with Dean, but no record of the final disposition has yet been found.

Dean worked for the army as the civilian athletic director and baseball coach at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and in the same role at a post in Germany. He later held jobs as a New Jersey highway inspector and a salesman. He died of a heart attack at 55 on December 21, 1970, survived by his wife and a daughter.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Notes

1 Norman L. Macht, The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 103.

2 “New Hope Springs for A’s at Springs,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), February 13, 1941: 2.

3 Norman L. Macht, The Grand Old Man of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 118.

4 C. William Duncan, “Chubby Dean, Who Took Short-Cut Across Campus, Pinch Hits His Way to Majors,” TSN, August 20, 1936: 3.

5 Macht, 115.

6 James C. Isaminger, “Convention Brings New Phil Platform,” TSN, July 2, 1936: 3.

7 J.C.I. (James C. Isaminger), “The Old Scout’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1936: 17.

8 Isaminger, “Mates Say Mickey Won’t Catch Again,” Inquirer, September 18, 1937: 19.

9 Cy Peterman, “The Science of Pitching Also Aided by Thought,” Inquirer, June 26, 1940: 31.

10 Peterman, “The Science of Pitching.”

11 Stan Baumgartner, “Dean Third Mack to Sign Contract,” Inquirer, January 12, 1941: S-4.

12 Baumgartner, “Dean, M’Coy on Spot This Year,” Inquirer, February 27, 1941: 25.

13 “Dean A.W.O.L.,” Inquirer, August 25, 1940: S2.

14 Chris Holaday, ed., Baseball in the Carolinas, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 58.

15 Baumgartner, “Dean Third.”

16 “A’s Suspend Chubby Dean,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1941: 21.

17 Phil Marchildon with Brian Kendall, Ace: Phil Marchildon, quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside/Simon & Shuster, 2004), 180.

18 “Dean, Graduate First Baseman, Prefers to Battle for Mound Job,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 2, 1942: 12.

19 Gordon Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 26, 1942: 18.

20 Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 4, 1943: 14.

Full Name

Alfred Lovill Dean

Born

August 24, 1915 at Mount Airy, NC (USA)

Died

December 21, 1970 at Riverside, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.