Dave Brown

The case of 1920s Negro League pitcher Dave Brown provides a classic example of the oft-quoted line, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” a maxim that stems from a John Ford-directed film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In that movie, reporter Maxwell Scott (Carleton Young) discovers that his subject, Senator Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), has built his entire reputation on the lie-become-legend that he killed an outlaw named Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin); the fact is that Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) was the man who shot Valance. Although Scott learns the truth, he utters the film’s famous line to indicate that he is more interested in newspaper sales than facts. Until the year 2023, the “facts” of Brown’s life story seemed odder than any fictional tale possibly could be, but it turns out that there were some legends mixed in, too. New discoveries now have revealed much of the truth. Brown’s actual life story still provides plenty of twists and turns and is, in many ways, more compelling than the original myths.

The case of 1920s Negro League pitcher Dave Brown provides a classic example of the oft-quoted line, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” a maxim that stems from a John Ford-directed film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In that movie, reporter Maxwell Scott (Carleton Young) discovers that his subject, Senator Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), has built his entire reputation on the lie-become-legend that he killed an outlaw named Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin); the fact is that Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) was the man who shot Valance. Although Scott learns the truth, he utters the film’s famous line to indicate that he is more interested in newspaper sales than facts. Until the year 2023, the “facts” of Brown’s life story seemed odder than any fictional tale possibly could be, but it turns out that there were some legends mixed in, too. New discoveries now have revealed much of the truth. Brown’s actual life story still provides plenty of twists and turns and is, in many ways, more compelling than the original myths.

Dave Brown, a southpaw flinger, became one of the early pitching stars in the Negro National League with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. Allegations that he had scrapes with the law in his native Texas before he joined Foster’s squad, or in Chicago shortly thereafter, are part of his story; however, it is highly likely that Foster fabricated the charges in 1923 after Brown jumped his contract with Chicago.

In 1925 Brown became wanted for murder after it was alleged that he shot a man to death in New York City, and he went on the lam. In a time when communication was still limited, Brown was able to elude the police and the FBI, of which famed director J. Edgar Hoover had taken control one year earlier. While on the run, Brown used the alias William “Lefty” Wilson as he pitched for numerous semipro aggregations throughout the Midwest. Brown played under the Wilson alias until 1932, after which time he disappeared. Then, in 1938, a man named Dave Brown was arrested for assault and robbery in Greensboro, North Carolina.

It appeared that Brown’s past had caught up to him by most unusual circumstances before he became a free man and disappeared for all time. At least, that was the story until 2023, but the facts – rather than the legends – are now known and presented here.

Dave K. Brown was born on June 9, 1897, in Marquez, Texas, a small town in Leon County approximately 68 miles southeast of Waco.1 His parents, Silas and Anna (Walton) Brown, were farm laborers, and Dave was their ninth and last child.2 Mystery surrounds the story of Brown’s life from birth. For reasons unknown – though it may have been as simple as the fact that his place of residence changed – Brown filled out two World War I draft registration cards that contained slightly different information. In June 1917 he gave his birthdate as June 9, 1895, and indicated that he was a “Ball Player” in the employ of Enos Whittaker, owner of the Texas Colored League’s Dallas Black Giants team. However, in August 1918, he provided June 9, 1897, as his birthdate and stated that he was a warehouse worker in Dallas; this may have been a second (or offseason) job, since he was still pitching for the Black Giants that year. Documents, including official military service records, show that Dave’s brother Felix was born on January 18, 1895, and the 1900 census listed June 1897 for Dave’s birth; thus, the year 1897 appears to be the correct birth year for Dave.

Nothing is known about Brown’s childhood or how he developed his baseball skills, but his pitching talent garnered him a position on the Dallas team in 1917. On June 6, just three days before his 20th birthday, Brown pitched for the Black Giants in a 5-3 loss to the Hot Springs Bear Cats; his catcher that day was Jim Brown.3 The two Texans gained renown as “the Brown Battery” and soon moved into the next stage of their careers together. Oliver Marcell, who went on to hit .306 over 13 seasons in the Negro major leagues, was also in the Dallas lineup in 1917.

One week after the game against Hot Springs, on June 14, Brown earned what may have been his first professional victory as he pitched all 12 innings in a 4-3 triumph over the same opponent. Hot Springs’ starting pitcher was listed only by the nickname “Nacogdoches” – presumably, a nod to the hurler’s hometown – and the press noted that “[t]he game was witnessed by a good crowd, about half the spectators being white persons.”4

Brown returned to the Black Giants for the 1918 season. On May 24 he struck out 11 batters in a 7-0 whitewashing of an Army team from Camp Travis, Texas, in the first game of a doubleheader.5 Brown had become a local star as was evidenced by the fact that news articles used his name to draw fans to coming games. For an August game against the Fort Worth Wonders, one newspaper noted, “Dave Brown has been nominated to pitch for the Giants” and “[m]usic will be furnished by a brass band.”6

In the spring of 1919, fellow Texan Rube Foster signed the Brown Battery for his Chicago squad, which was in its final season as an independent team. Once again, though, mystery and rumors surround the circumstances by which Brown moved into the next phase of his career. In an April preview article about the American Giants, the Chicago Defender reported, “No one in the world knows better how to pick a player than ‘Rube.’ … Brown and Brown of the Dallas, Tex., Giants are here. They were a whirlwind in Texas.”7 No mention was made of any special circumstances by which Dave Brown was obtained, either at that time or during any other point in Brown’s tenure with the team.

However, in 1923, after Brown had jumped his contract with Foster and joined the New York Lincoln Giants of the Eastern Colored League, Rube related a different tale. Foster may have invented this new narrative out of anger, as no contemporary documentation has yet come to light to corroborate it. He asserted about Brown:

“He did not leave because he was not treated right nor because his salary was not remunerative enough for his services. He simply wished to compensate me for staking the reputation of the American Giants baseball club and my own when convicted and sentenced to the penitentiary for highway robbery by going into court and having him paroled to me; this being done by me giving bond for $20,000 for him.

“This was before Dave Brown showed any real pitching ability. It was when he had only pitched two games for me during the season. I promised his mother to take care of him if he came to Chicago and it was this promise that I was carrying out.

“Should I now get down off of that parole, he would have to serve his sentence.”8

Foster asserted that he had dirt on numerous players, in addition to Brown, that “would shock the public beyond measure.”9 There is no question that some ballplayers – no matter the era, their race, or their league – have committed shocking acts, but this screed sounded more like the grievances of a spurned suitor.

Foster’s claim about Brown seems dubious for numerous reasons. First and foremost is the question of whether Foster could finagle such a parole and whether he would have paid the large sum required for the bond.10 Second, the lack of any press coverage during or after the alleged crime is unusual, especially since Brown had become well known for his pitching in the Dallas area. It is noteworthy that, due to the way Foster’s statement was worded, it could be interpreted to mean he was asserting that Brown ran afoul of the law after joining the American Giants; however, no record exists of Brown having been arrested, let alone being tried and imprisoned, in Illinois or the closely neighboring states of Indiana and Michigan. Thus, there is no evidence to corroborate Foster’s claims about Brown’s alleged crime.

Whether or not Foster ever met Brown’s mother so that he could promise her to take care of Dave is also questionable, but it is the one element of the story that might have a grain of truth considering what happened to one of Dave’s older brothers, Webster. According to one news account, Webster Brown, who was six years older than Dave, was “a bad man generally” and was “well-known in police circles in the southwest.”11 On January 31, 1919, Webster led Dallas police on a chase that ended with him being shot and killed. It was reported that the chase “resulted from a theft of clothing that occurred yesterday [January 30] afternoon.”12 Captain J.C. Gunning, chief of detectives, said that Webster “had been in jail several times and was an escaped convict from the county farm.”13 If Foster did meet Anna Brown in 1919, after Webster’s violent death, it is possible that she asked him to look after Dave in the hope that her youngest son would stay out of trouble. It is also quite likely that, in his fit of pique in 1923, Foster attributed Webster’s criminal history to Dave to smear his reputation.

After Brown joined Foster’s squad in 1919, he was used sparingly at first. Officially, he is credited with a 1-2 record and a 4.40 ERA in games pitched against other top-caliber Western Independent Clubs.14 He also pitched against semipro aggregations and notched one of his earliest victories for Chicago against the Nash Motors team of Kenosha, Wisconsin, on May 11. Brown, who was identified in the press as “the new southpaw of the Giants,” pitched Chicago’s third consecutive shutout in a 5-0 complete-game effort; he scattered four hits while walking three batters and striking out three.15 The Chicago American Giants finished the 1919 season with a 27-16 record that was second-best in the West to the 27-14 mark posted by the Detroit Stars. But there was no league and, therefore, no pennant to be won. However, that was no longer to be the case after Foster and his fellow team owners founded the first Negro National League at the Paseo branch of the YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri, on February 13, 1920.16

Chicago dominated the early years of the NNL, claiming the first three league championships from 1920 through 1922 with Brown contributing a composite 43-8 record in league play during those seasons. Brown’s first appearance in an official NNL game took place on May 9, 1920, against the similarly named Chicago Giants at Schorling Park, the American Giants’ home field. According to the press account of the game, “while Dave Brown was on the rubber, [the Giants] simply could not see his offerings” as he hurled six shutout innings to earn the win.17 He ceded the mound to Tom Williams with an 8-0 lead in what ended as an 8-3 triumph, but it was an auspicious debut that heralded 1920 as Brown’s breakout season.

As the American Giants rolled to a 43-17-2 record (a .717 winning percentage) in NNL games to claim the pennant by eight games over the Detroit Stars, low-hit, low-run outings became the norm for Brown. In addition to capturing the ERA title with a 1.82 mark – albeit edging out teammate Tom Williams by only 0.01 – Brown paced his team in victories with a 13-3 record that also put him in a tie for fourth in the league – two wins behind Detroit’s Bill Gatewood. Brown also tied for fourth in the league in strikeouts with 101, five behind the league-leading total of Kansas City’s Sam Crawford. Perhaps the most remarkable statistic of all was Brown’s 0.908 WHIP as he allowed only 84 hits and 51 walks in 148⅔ innings pitched.

At the conclusion of the 1920 NNL season, Foster took his squad on a swing through the South in late September and early October. The American Giants emerged victorious against all opponents and repeatedly clubbed the Negro Southern League’s champion, the Knoxville Giants, into submission. Chicago defeated Knoxville at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field on September 21, 22, 23, and 30. The two teams met again in Knoxville on October 2 as Brown opposed Steel Arm Dickey in a classic pitchers’ duel. The game remained scoreless until the bottom of the eighth inning, when Knoxville, which managed only three hits, broke through with the contest’s first tally. Chicago came back with two runs in the top of the ninth, and Brown shut down Knoxville’s lineup in the bottom of the frame to give the American Giants their 14th consecutive victory, a triumph that, according to Negro League historian James A. Riley, “sealed their status as the best black ball club in the country.”18

It certainly seemed that Foster was bent on his team’s laying claim to being the best in the nation as next they traveled northeast to take on the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants in a series of games played at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park and Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. This series was to serve as “a dress rehearsal for what Rube envisioned as the black World Series.”19 The Bacharach team proved to be a stiffer challenge than Knoxville had, but Chicago emerged with a 4-3-1 record in the series against the East’s top independent club, and the American Giants reigned supreme in 1920.20

In 1921 Brown and the American Giants picked up where they had left off the previous season. Foster’s team claimed its second straight NNL pennant as its 44-22-2 record resulted in the league’s best winning percentage (.667); the Kansas City Monarchs won more games, posting a 54-41 (.568) league ledger, but finished 4½ games behind Chicago. Brown once again paced the American Giants’ pitching staff and was among the NNL leaders in every major category. He tied for first in wins with 17, though his 17-2 mark was far superior to St. Louis hurler Bill Drake’s 17-11 record; his 2.50 ERA was second only to Bullet Rogan’s 1.72 mark for Kansas City; and his 126 strikeouts were tied for third, 14 behind league leader Bill Holland, a late-season addition to the American Giants who had spent the bulk of the season with Detroit. Brown’s five shutouts put him in a tie for first place with Jim Jeffries of Indianapolis, and 1-0 games proved to be his forte.

On August 14 Brown faced Drake and the St. Louis Giants at Schorling Park in what the Chicago Defender raved was “one of the best games – if not THE best – played at this park this summer and a humdinger of a pitchers’ battle.”21 Neither hurler surrendered a hit until the bottom of the seventh inning, when Bingo DeMoss singled off Drake, and the game remained scoreless until the bottom of the eighth. At that point Cristobal Torriente led off Chicago’s half of the inning with a single, advanced to second on catcher George Dixon’s sacrifice, and then stole third base. Floyd “Jelly” Gardner then beat out a bunt on a squeeze play, and Torriente crossed home plate with the game’s only run. According to the Defender, “Hats were broken and every stunt possible was pulled off by the rabid fans,” who now wanted to see Brown finish his no-hitter.22 However, such history was not in the making that day as St. Louis catcher Sam Bennett led off the ninth with his team’s first safety; Sidney Brooks ran for Bennett and was promptly erased when Drake grounded into a double play. Doc Dudley garnered the second hit against Brown, a single to right field, but the game ended when Dixon threw Dudley out at second base on a steal attempt.

Slightly less than a month later, on September 11 at Schorling Park, Brown engaged in another duel against Steel Arm Dickey and the Negro Southern League’s Montgomery Grey Sox. Although Dickey now plied his trade for a different team, the game was almost an exact replica of the previous year’s matchup between the two aces. There was more traffic on the basepaths on this day, but neither team managed to score for the first eight innings. Prior to the bottom of the ninth, the most exciting event had occurred off-field in the bottom of the seventh inning. The Defender’s Frank Young described the incident in a clipped style:

“Someone over on Wentworth avenue [sic] shoots a gun out of a house window. A hundred fans on top of the house watching the game begin to scatter. Finally[,] a bluecoat goes over and all of a sudden we see the housetop empty. We also see the bluecoat take out a white handkerchief and wave to us. Means all is at peace.”23

Everyone on the field and in the stands managed to calm themselves and the on-field action resumed.

With the game still scoreless, Brown led off the bottom of the ninth with a single but was forced at second on Jimmie Lyons’ fielder’s-choice grounder. Lyons bolted to second on a wild pitch by Dickey. DeMoss attempted a sacrifice bunt and ended up safe at first on a throwing error, with Lyons advancing to third. DeMoss then attempted to steal second, and Lyons scored when the Grey Sox catcher’s wild throw to second rolled into the outfield. Once more, the American Giants had clinched a 1-0 victory in the ninth with Dave Brown emerging as the winning pitcher.

At the conclusion of the NNL season, Foster again took his team east to play two series against the region’s most powerful independent clubs, the Bacharach Giants and the Hilldale Club of Darby, Pennsylvania. As had been the case in 1920, Foster intended these clashes to be “a dry run for the planned future ‘East-West World Series,’” and they were sometimes already billed as championship series in the press.24 However, this time around, Chicago struggled to stay even against both squads, so much so that Foster entered into damage control mode and “reminded everyone that the American Giants had won the NNL pennant.”25

Things went downhill from there for Foster as 1921 neared its end. He was arrested (and quickly bailed out) for alleged fraud in Atlanta, canceled the American Giants’ planned trip to Cuba due to political turmoil on the island nation, and, most tragically, suffered the unexpected death of his 5-year-old daughter, Sarah, on the train ride home to Chicago after an exhibition series in New Orleans. Despite his grief, Foster tended to the business of the NNL and wrote a series of blunt articles for the Defender in which he outlined the challenges for the league; the most controversial piece voiced Foster’s opposition to hiring Black umpires as arbiters for NNL games.

Between Foster’s misfortunes, his controversial columns, and the fact that Dave Brown was the American Giants’ only pitcher to return from the 1921 championship team’s staff, the outlook for the Chicago nine was not as positive as in previous years. The American Giants opened the regular season at Schorling Park in early May with a tough series against the powerful Monarchs, who soon would supplant Chicago as the dominant force in the NNL. The Monarchs captured the first game, 5-1, and Brown made his first start in the second tilt on May 7. The game did not bode well for Chicago’s season.

The Sunday contest featured a matchup between two of Black baseball’s premier pitchers in Dave Brown and Bullet Rogan. So many fans wanted to witness the proceedings that problems began before the game ever started. The Defender described the chaos:

“Early in the afternoon, about two o’clock, the bleacher seat box office was closed. The fans in that section attempted to violate law and decency by jumping over the fence into the higher priced seats. Over 200 followed this course. The crowd surged into fair territory time and again during the game. The play was stopped and Rube Foster with two or three players pleaded with the populace to give the outfielders a chance to play.”26

Initially, the game itself went as expected. While it was noted that “Brown was not in his usual cool form. He walked men and was in many tight holes,” he and Rogan dueled to a 1-1 tie through seven innings.27 The Defender observed, “The sixteen thousand that crowded the park got just what they came out to see,” but the newspaper also had to add, “only they did not see the ending.”28 Kansas City scored to take a 2-1 lead in the top of the eighth inning. When Chicago came back to tie the game in the bottom half of the frame, the crowd went berserk. According to the game account, “The overflow broke loose. On the field they went. … That was all. They just couldn’t play. Folks wouldn’t let them.”29

The crowd became so unruly that play was called off and the game was declared a tie. In response, fans began to throw cushions and pop bottles at one another, and the outmanned police force at the field had trouble bringing the melee under control. The Defender declared that “[t]he most disgraceful scenes were enacted” and that “[i]n all Chicago’s baseball history it cannot be recalled that such actions have ever taken place at any park.”30

The American Giants won the last two games of the opening series, a sign that they would barely hold off the Monarchs and retain the NNL title for one more season. At the end of the 1922 NNL campaign, Chicago won the pennant by virtue of having an almost infinitesimally greater winning percentage than Kansas City: The American Giants’ 37-24-1 record gave them a .607 winning percentage compared with the Monarchs’ 47-31-2, .603 mark.

Brown certainly did not slump in 1922, posting a 13-3 record with 103 strikeouts and a 2.90 ERA in 155 innings pitched in NNL play. As usual, his numbers put him in the top five of most major pitching categories: He finished tied for third in wins (though considerably behind Jim Jeffries’ 21 victories for Indianapolis), fourth in ERA, and fifth in strikeouts. As had also become typical for Brown, he was involved in a stellar 1-0 victory, this time against the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants.

Chicago did not sojourn east in 1922. Instead, the Bacharachs and the Hilldale Club visited Schorling Park for the first time. On August 16, “[a] bit of history was made … when the American Giants were involved in one of the longest games ever in Negro League history[,]” against the Bacharachs.31 Ed “Huck” Rile started the game for Chicago, but Foster pulled him after four scoreless innings and sent Brown to the mound. Brown went 16 innings, an amazing feat but one that paled in comparison to that of his mound opponent, Harold Treadwell, who pitched all 20 frames for Pop Lloyd’s Bacharach squad. Eventually, one of the two hurlers had to tire, and it turned out to be Treadwell in the bottom of the 20th inning. Torriente drew a leadoff walk from the exhausted Treadwell and advanced to second on Bobby Williams’s sacrifice bunt. Dave Malarcher then banged out a single to drive in Torriente with the game’s only run, giving Brown yet another 1-0 victory and allowing Treadwell to ice his rubber arm.32

At the conclusion of the 1922 season, Brown was one of several Negro League players who traveled to Cuba to play winter baseball. His first foray to the island was unremarkable as he played for Santa Clara, which finished in last place with a 14-40 record and withdrew from the league on January 14, 1923.33 Brown distinguished himself via his 4-3 record, which tied teammate Eustaquio Pedroso (also 4-3) for the team lead in victories.34

By the time Brown returned from Cuba, Ed Bolden, owner of the Hilldale Club, had founded the Eastern Colored League to compete with Foster’s Western circuit.35 Soon thereafter, the Defender reported:

“Baseball fans in Chicago were much surprised last week when Dave Brown, first string pitcher for the American Giants, caught a rattler for New York. … It is strongly rumored that Brown will work for the Lincoln Giants this summer, making his exit from organized ball and jumping to the outlaws.”36

Teammate Ed Rile was also heading east, and the Defender alleged, “According to well founded [sic] rumors, Rile has been acting as an agent for the Eastern association in their raid on players belonging to the Negro National league.”37 Foster responded one month later with his story that he was disappointed in Brown’s disloyalty since he had bought him out of prison.38

Brown, who was leaving behind one former Dallas teammate, Jim Brown, was reunited with another old friend from his playing days in Texas, Oliver Marcell. He also appeared simply to shrug off Foster’s allegations, but his first season in New York was not a rousing success. The Lincoln Giants finished in fifth place with a 17-23 league record (18-23 overall). Brown pitched to a 5-6 record with 47 strikeouts and a 3.28 ERA in 74 innings. His totals still placed him in the top 10 – but no longer the top five – of most statistical categories in the ECL, but he was not even the best pitcher on his team. Bill Holland had 48 strikeouts and a 3.13 ERA in 72 innings pitched but was a victim of hard luck as he finished the season at 0-7.

Brown, Marcell, and Holland were three of the numerous Negro League players who joined the Santa Clara squad for the 1923-24 Cuban winter season. The now talent-laden team managed a 180-degree turnaround from the previous season, finishing in first place with a 36-11 record. In fact, this Santa Clara squad came to be “[c]onsidered as the most dominant team ever in the history of Cuban baseball by amassing an 11½ game bulge over their nearest rival.”39 Bill Holland led the team and league in wins with a 10-2 record, Rube Currie contributed an 8-2 mark, and Brown finished with a 7-3 ledger.

The 1923-24 Cuban season was such a popular success that fans clamored for more baseball, and a special season, named Gran Premio, was quickly arranged. Santa Clara finished with a 13-12 record that enabled it to edge out Almendares by a slim half-game margin. Brown (4-2) and Holland (4-3) tied for the team lead in wins in this second season.40

When Brown returned stateside in 1924, he was riding high from his Cuban experience and rejoined the New York Lincoln Giants with an eye toward a better outcome in the ECL’s second season. After Brown won the second game of a doubleheader against the Washington Potomacs, one of the ECL’s two new squads, on May 18, the “rejuvenated Lincoln Giants” had run out to a 7-2 record.41 One week later, the Lincoln Giants ran their win streak to eight by sweeping a doubleheader from the Bacharachs, and they led Hilldale by a half-game in the standings.42

The Lincoln Giants greatly improved their performance in 1924, but they could not sustain their quick start. The team and Brown faded down the stretch, a fact that was clearly in evidence by a late-September sweep suffered at the hands of the Cuban Stars. Brown lost the second game, 7-0, and the press noted that he “put his team at a disadvantage in the very first inning by walking two men and then allowing two hits, causing four runs to be made.”43

Hilldale won the ECL title with a 47-26 record while the Lincoln Giants finished third, seven games back, with a 35-28-1 record. Foster had to be chagrined that two of his Chicago team’s rivals, Bolden’s Hilldale club and the NNL’s Kansas City Monarchs, faced off in the first-ever Negro League World Series. The Monarchs captured the title in 10 games, with one game resulting in a tie.

As for Brown, he returned to the old form he had exhibited with Chicago. He led all ECL pitchers with a 2.00 ERA, and his 13-8 record and 107 strikeouts were second only to Hilldale’s Nip Winters, who finished the year at 20-5 and struck out 114 batters. Brown would have been the darling of the modern sabermetric crowd, however, which would point out that he finished with an ERA+ of 241 compared with Winters’ 142, thus denoting him as the far superior pitcher.

In the winter, Brown returned to Cuba, where he again toiled for Santa Clara. The team’s fortunes went up and down like a yo-yo, and the 1924-25 campaign was a down time. The squad finished in third place with a 20-28 record and “attendance at the games in Santa Clara’s Boulanger Park was so disappointing … that in early January owner Abel Linares moved the franchise to Matanzas.”44 Brown’s performance typified the moribund team’s fortunes: His final foray to the island resulted in a 2-4 record.45 At least he could look forward to competing for the ECL title with the Lincoln Giants in 1925.

Or so Brown and everyone else thought after an Opening Day doubleheader against the Bacharachs on Sunday, April 26, that kicked off the regular season for both teams. Brown, who started the first game, “was the master of the Atlantic City boys throughout the fray, allowing them seven scattered hits and only [being] scored upon once.”46 After winning the first game, 6-1, the New Yorkers also captured the nightcap, which turned into a 10-inning affair, by a 4-3 score. The sweep was a sweet start to the season.

Teammates Brown, Marcell, and Frank Wickware (who had played for the American Giants in 1920) apparently spent two days celebrating their early success. In the wee hours of the morning on Tuesday, April 28 – at 3:25 A.M., to be precise – as the group returned home from a night of carousing, a man named Benjamin Adair was shot in their presence at 69 West 135th Street and was taken to Harlem Hospital, where he was declared dead on arrival.

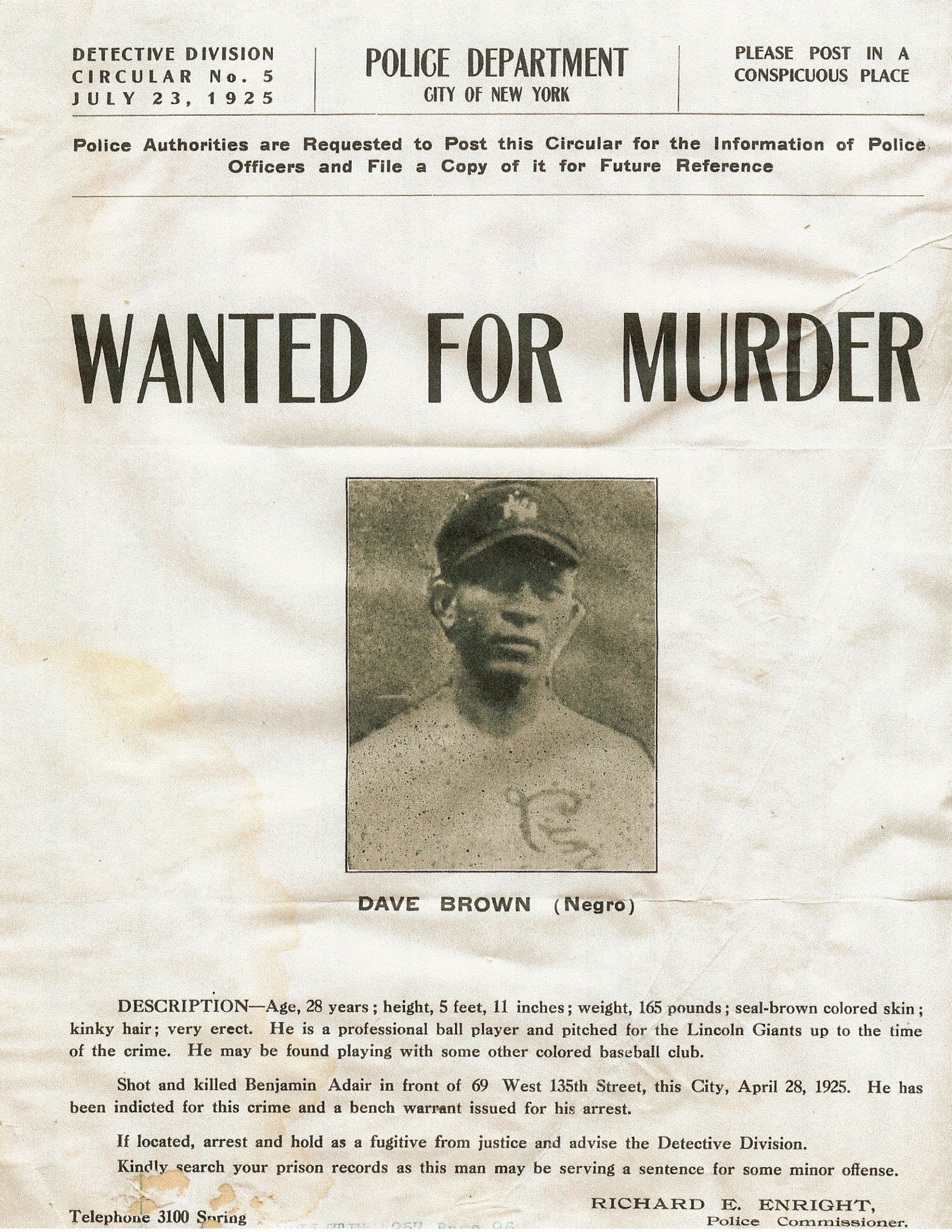

(Photo: Courtesy of Larry Lester / NoirTech Research, Inc.)

Published accounts of this watershed event in Brown’s life vary wildly. Negro League historian James A. Riley wrote in 1994, “After killing a man in a barroom fight that year, apparently in an argument involving cocaine, he dropped out of sight to avoid arrest on a murder charge.”47 Subsequently, the assertion that Brown shot Adair has always been taken at face value with some contemporary articles being misread and others ignored entirely. Yet no contemporaneous news accounts reported that the shooting took place in a bar or that a drug transaction was involved.

Additionally, newspaper reports provided contradictory descriptions of the exact events of the incident despite the presence and testimony of several eyewitnesses. The New York Evening Journal reported that Adair “was with several women and three men when the shooting occurred” and “[a]s the party passed No. 69, a man with a revolver ran to the street shouting: ‘Now, I’ve got you.’ When Adair fell to the pavement his companions fled.”48 The New York Evening Post, on the other hand, wrote, “As he was about to enter his home at 61 West 135th street [sic] at 3 A. M. today[,] Benjamin Adair, a negro, twenty-nine, was killed by an unidentified assailant who stepped from a nearby hallway and fired four shots.”49

More confusion is added by the New York Amsterdam News’s assertion that Adair and “four men were quarrelling on the sidewalk, when one of them drew an automatic and fired one shot at him. As he crumpled to the sidewalk[,] the four jumped into a passing cab and drove away. It is said that all four are unknown to the police.”50 On May 2 the Chicago Defender claimed, “Information gathered from eyewitnesses of the shooting discloses the fact that Adair was a marked man and that the murderers planned their deed carefully, although their motive has not yet been discovered.”51 The Defender also wrote that “four men standing in the shadows near [Adair’s] steps drew revolvers and opened fire. Two bullets entered Adair’s body, killing him almost instantly.”52

The Philadelphia Tribune’s May 2 edition stated that Adair was walking “with three friends … when four shots were fired from the dark doorway at No. 69. … His three companions said they saw no one and police could not find the revolver or discover any motive for the shooting.”53 The New York Age was the first newspaper to report, also on May 2, that Brown and his two teammates might have been involved in the incident.54

The eyewitnesses who were questioned by police had taken down the number of the taxi in which the alleged perpetrators had escaped, and police arrested the driver, William Holland (not to be confused with pitcher Bill Holland). Holland stated that “he took the men as he would have taken any other passengers. He denied having seen them before.”55 Upon checking out Holland’s story, the police released him.

The Lincoln Giants canceled practice on April 28 because they were missing three players that day – Brown, Marcell, and Wickware. On May 16 the Baltimore Afro-American ran an article indicating that the “[p]olice of Atlantic City have been unable to locate the whereabouts” of the three ballplayers.56 Furthermore, the Afro-American provided yet another variation on the events of the shooting: “According to witnesses[,] the three ball players and Adair were passing in front of the 135th street [sic] address when a man ran out of the building and shouted, ‘I’ve got you,’ and fired point blank at Adair, who dropped mortally wounded.”57 It is unclear whether the article was stating that Adair and the ballplayers were companions or that they were simply in the same place at the same time. Their disappearance lends credence to the idea that they were Adair’s companions and perhaps feared trouble for themselves if Adair had brought his violent death upon himself by some previous criminal action. In any case, the trio were certainly additional eyewitnesses who cast suspicion upon themselves by leaving the scene of the crime and evading police for a time.

The Lincoln Giants traded Marcell to the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants in mid-May58 only to reacquire him one month later. In reporting about Marcell’s return to the Lincoln Giants on June 20, the New York Age noted, “The former Lincoln captain had the misfortune to witness a murder on 135th street [sic] about two months ago and was wanted for a time as a material witness in the case. However, no charge was ever made against him.”59

Wickware also had been cleared of any wrongdoing in mid-May. The Chicago Defender reported on May 23 that he “was freed in the Manhattan homicide court this morning [May 16] of charges in which he was held as a suspect in the killing of Ben Adair. … The move came after the district attorney stated that his office held no evidence against the accused to connect him with the murder.”60

With Marcell and Wickware having been apprehended, questioned, and cleared, it remains unexplained why Brown never turned himself in to the police. It does not appear that any of the ballplayers had a role in the Adair shooting; if so, all three should have been charged with a crime. Perhaps Brown saw himself as a potential scapegoat since he was the only identified witness, or suspect, left. He may also have called to mind the shooting of his brother Webster in Dallas and had a distrust of the police and how he would be handled if he turned himself in. There remains the possibility that Adair was involved in criminal activity, perhaps indeed involving drugs, and Brown was afraid to suffer any consequences due to guilt by association. Nonetheless, after the New York City police made no progress in their investigation for a couple of months, they released the only known wanted poster in history with a photo of the alleged perpetrator wearing a baseball uniform. The poster declared that Dave Brown was wanted for murder.

W. Rollo Wilson of the Pittsburgh Courier had taken the three players to task in his May 9 Pittsburgh Courier column, asserting, “Whatever the outcome of this matter these men must leave the game. The integrity of the pastime demands it.” Of the New York team’s fortunes, Wilson wrote, “The serious trouble in which Dave Brown, Wickware, and Marcelle are involved will just about wreck the Lincoln Giants.”61 That much was certainly true as the team finished the season in last place with a dismal 7-41 record. As for the three players, Marcell played through the 1930 season; the 37-year-old Wickware’s career ended after 1925; and Brown soon reappeared under an alias.

In the summer of 1926, newspapers in the Midwest began to report the exploits of a pitcher named Lefty Wilson, who played for various semipro teams throughout the region. As a member of Gilkerson’s Union Giants, Wilson dominated local competition in Iowa. On June 20 he notched an 11-4 victory over Davenport’s Knights of Columbus team, with the local newspaper noting that he “eased up slightly in the latter innings” to allow the Knights to score.62 Wilson extended no such courtesy against the Spencer team – the state semipro champion – on July 10 in Mason City, Iowa. He struck out 17 batters while allowing only one hit, one walk, and a hit batsman in a 2-0 triumph.63

Shortly thereafter, Wilson pitched for the Pipestone, Minnesota, Black Sox. In a 7-2 victory over a team from LeMars, Iowa, the “well-known negro pitcher twirled for the visitors and held the home club under control at all times.”64 The player wanted for allegedly shooting a man with a real gun now became a figurative hired gun for any semipro team that wanted to pay him, though he played mostly for teams from Iowa and Minnesota.

In 1927 Wilson joined the team in Wanda, Minnesota, and helped lead it to the Tri-County League championship by defeating Comfrey in two games – 8-1 and 2-1 – while striking out 10 and 13 batters respectively. Wanda played the Franklin Creamery team from Minneapolis in the state tournament in St. Paul, but Wilson ended up on the losing end of a 6-0 game.65

Still, Wilson was ready to return to Wanda in 1928, but the Tri-County League had issued an edict aimed directly at him. The league decreed, “The rules under which the circuit operated last year were approved with the exception that the color line was drawn and the status of home players was defined.”66 With that ruling, Lefty Wilson’s time in the Tri-County League came to an end. However, he stayed in Minnesota and played for the team in Bertha, becoming the team’s ace after the departure of Negro League legend John Donaldson.67

In a day when communication was limited, it was easy for Brown to assume his new identity as William (Bill) “Lefty” Wilson in a different part of the country from where the crime for which he was wanted had taken place. The difficult element of evading the police lay in the fact that he was well known from his days with the Chicago American Giants, and many semipro teams played against Negro League teams or fellow semipro squads that hired former Negro League players. On June 14, 1928, it was announced that John Donaldson and Lefty Wilson would be the mound opponents in a game in Bertha, with Wilson pitching for the home team.68 Donaldson had been a member of the Kansas City Monarchs in 1920-21 and no doubt recognized his opponent as being Dave Brown, formerly a member of the Chicago American Giants.

No former teammates or opponents ever revealed that ace semipro pitcher Lefty Wilson was the wanted fugitive Dave Brown. Although the reasons for players’ silence are unknown, it is possible that they either learned of Brown’s innocence from Marcell or Wickware, or that they shared Brown’s distrust of the police due to America’s unfortunate history of racial violence. Various players, including Hall of Fame shortstop Willie Wells and former Colored House of David catcher/teammate L.J. Favors, admitted in later years that they were aware of Wilson’s true identity. Both players claimed that teams that employed Wilson always kept their bags packed in case someone – primarily the police – learned who he was and their team had to depart quickly in the middle of the night to avoid trouble.69

Wilson finished with a 14-8 record for Bertha in 1928, but the team’s attendance was so low that the owner joined a new, small-town league for 1929 that allowed its teams to use only home talent on their rosters. The second loss of employment in Minnesota did not faze Brown, who took his Lefty Wilson act back to the state of Iowa in 1929.70 By this time, obviously emboldened by the fact that no one had turned him over to the law, Brown, although he maintained his alias, did less and less to conceal his past and his identity.

On April 14, 1929, it was reported that Lefty Wilson would take the managerial reins for a Sioux City, Iowa, team sponsored by the Auto Kary-All Manufacturing Company. According to the local press, “‘Lefty’ Wilson, regarded as the greatest negro southpaw hurler in the game and formerly a member of the Chicago negro National league [sic] club, has been signed as manager and has secured a lineup of players from Scott’s Giants, Gilkerson’s Union Giants and negro league clubs.”71 The Chicago American Giants never had a pitcher named Wilson, but apparently Brown wanted to tout his past accomplishments and attributed them to his new alter ego without any concern for blowing his cover. Not only was Brown not lying low from people who might recognize him, he was now audacious enough to recruit players from Negro League teams.

The Kary-All nine did not receive extensive coverage. However, if the team’s May 11 game against the Kari-Keen squad was representative of their efforts, the team and its pitcher-manager did not fare well. In what the press termed a 12-5 “drubbing,” it was stated that “[t]he winners hammered ‘Lefty’ Wilson for 14 hits in six innings and had the game ‘sacked up’ before he was relieved by Truesdale.”72 By August, whether Kary-All’s season had ended or not, Wilson was a member of the Cubans, John Donaldson’s barnstorming team.

On August 29, in a game against the House of David team, “‘Lefty’ Wilson, the colored pitcher who had reached second base, started a chewing match [with the House of David shortstop] that ended in a real fistfight that took several of the players to separate.” Home-plate umpire Bunny Clouton ejected both players, but the House of David shortstop refused to leave the field. Eventually, to get the player to depart, Clouton agreed to be replaced by fellow arbiter Scoop Hunter. The fistfight and dispute over who would umpire the game took so much time that the game had to be called on account of darkness in the seventh inning.73

In 1930 and 1931, Lefty Wilson pitched for the Colored House of David team with varying degrees of success. He had, however, made quite a name for himself in the Midwest. After he pitched the Colored House of David to an 8-6 victory over the Cold Spring, Minnesota, team on June 21, 1930, the press noted, “‘Lefty’ Wilson, well known in this community, did the chucking for the Davids against Cold Spring on Saturday,”74 The following year, Wilson was mentioned as the possible starting pitcher for the Davids, who were “considered one of the outstanding negro teams in the country, in a preview article for a game between the Colored House of David and a team from La Crosse, Wisconsin, that was to take place on August 31, 1931.”75 Perhaps the last report of Lefty Wilson was as a pitcher for the Fineis Colored Giants of Grand Rapids, Michigan, in an August 1932 recap of a doubleheader against the original (White) House of David ballclub.76

Lefty Wilson then faded into history, but Dave Brown resurfaced six years later in North Carolina. That is, on July 15, 1938, “David Brown, 30-year-old negro, was taken into custody by Greensboro police and held for questioning … following an incident in which Jess [sic] Wells, white man, was said to have been pushed from the porch of a residence. … Wells, in an unconscious condition, was taken to Piedmont Memorial hospital around 3 o’clock. It is thought possible that he suffered a fractured skull.”77 Wells regained consciousness that night and identified Brown as his assailant. The next day a warrant was issued against Brown that charged him with robbery with deadly weapons since he also had taken $4 from Wells in the assault.

When this Dave Brown was brought to the police station, he wore a “glossy green shirt” that “gave him an unusual appearance and he was questioned as to athletics.”78 He confessed that he had played baseball at one time but claimed that he had never been a professional ballplayer and that he had never been out of North Carolina. Upon his admission that he had played ball, a detective “recalled the 13-year-old poster with the picture of a man wearing a baseball suit in the center thereof.”79 Police dug out the poster and believed there to be some resemblance between the photo of the ballplayer Brown and the man they had in custody. The suspect was photographed and fingerprinted, and the information was forwarded to the authorities in New York.

On July 22 the Greensboro police received word that their prisoner was the same man on the wanted poster and were asked whether Brown would agree to waive extradition. Brown agreed, and awaited transport to New York, where he was to stand trial for murder. What happened next is best described by a one-word headline in the July 31, 1938, Raleigh News and Observer: “Lucky.” The news article explained:

“Today a telegram came from the New York police saying that all witnesses had disappeared in the intervening 13 years, and that since Brown could not be convicted, the charge would be dropped. When the Greensboro police turned to the local offense, they found that Wells had left Greensboro. There was nothing to do with Brown except turn him loose.”80

The Greensboro police did exactly that and, until 2023, this was believed to have been the last certainty in the life of Dave Brown, Negro League pitching ace of the early 1920s.

In retrospect, a closer examination of some inconsistencies involved in the Greensboro incident points to the likelihood of this event involving a case of mistaken identity. For one thing, Dave Brown the ballplayer was already 41 years old in 1938 while Dave Brown who was in custody was 11 years younger. This means that New York police were matching the photo of a 28-year-old player, taken in 1925, with a photo of a 30-year-old; thus, the photos might have been more of a match than they would have been between individuals aged 30 and 41. Notably, within one day, the Greensboro Daily News went from asserting that the description on the wanted poster “tallied closely”81 with the Dave Brown in custody to stating only that he “answer[ed] somewhat the same description.”82 In modern times, the fingerprints would be irrefutable evidence, but New York police had no fingerprints from Dave Brown to try to match to the Greensboro prints. Even if they had had them, they lacked the modern databases with which to make a certain match.

As it turns out, Dave Brown in Greensboro only shared a name with the famous ballplayer, who already was living in California, the state in which his older brothers, William and Felix, and sister, Eva, had settled after leaving Texas. There are still brief gaps in Brown’s life story, and exactly when he moved to California and adopted the alias Alfred Basil Brown is unknown. He may have traveled west as early as 1932 after the baseball season ended. He certainly already was residing in the Golden State by 1937, when an event occurred that changed numerous lives, including Brown’s.

Since Brown now lived in California and had no connection to North Carolina, it is unlikely that he was the individual who had been arrested in Greensboro. The most compelling argument for the incident having been a case of mistaken identity is the fact that Dave Brown the ballplayer used the new alias and falsified some of his background information. Obviously, he still believed himself to be a fugitive wanted by the law. Had he been the individual in Greensboro, he would have known that he now was a free man and could have dropped all aliases and pretenses.

In 1937, Alfred (Dave) Brown and his wife, Faye L. Charles, were residing in Marysville, California. On February 7, in that city, a man named Valenten Flores shot and killed Adris Carino and his wife, Pastoria Rico Carino, before turning his gun on himself in a double-murder-suicide. Flores had been a boarder in the Carino household but had been evicted after making unwanted advances on Mrs. Carino. To make matters worse, the shootings took place in a poolhall in front of the couple’s young children – a son, Terry, age 3, and a daughter, Frances, 2.83 The children’s maternal uncle, John Rico, gained custody of them.84 Rico was Alfred Brown’s co-worker. He was also single and, apparently, he did not think he could properly care for the children. In stepped Alfred and Faye Brown, who eventually adopted the two youngsters and raised them as their own.85 The irony that a man living under an alias, who was accused – most likely, wrongfully – of murder adopted two children whose parents were murdered is a turn of events that most people expect to encounter only in a mystery novel.

At the time of the 1940 US Census, the Browns were still living in Marysville as were the Rico children, who still resided with their uncle. Alfred’s (Dave’s) occupation was listed as “laborer,” but his class of worker was given as “wage or salary worker in Government work,” as he was employed by the US Post Office for a time. The Census also shows that Dave gave his birth year as 1902 and birth state as Illinois, and he claimed that his parents had both been born in Michigan. In 1942 Dave filled out a World War II draft registration card for which he provided the full name “Alfred Basil Brown.” He claimed his birthdate was June 9, 1901, and that he had been born in Chicago.

Just as Dave Brown had kept part of his past intact in his Lefty Wilson years, namely his tenure as a member of the Chicago American Giants, he now mixed fact with fiction under his new alias. His last name truly was Brown. He had been born on June 9 but in 1897 rather than 1901. And he had achieved baseball stardom in Chicago, though he had not been born there.

By 1948, the Browns had adopted Terry and Frances Rico, and the family had moved to San Francisco, where Faye operated a beauty salon while Alfred worked as a house painter, which remained his occupation until his death. At some point in the 1950s, the family moved to Spokane, Washington, where Alfred and Faye were officially married on July 23, 1956. The Browns had raised their adopted children to adulthood – they never had any biological children of their own – and Dave lived his new life as Alfred, the house painter. After Faye died on November 9, 1981,86 Brown moved back to California, where he settled in Los Angeles. When his sister, Eva, died in Madera (near Fresno) in July 1983,87 he was the only one of his siblings still living.

Alfred Basil Brown, once better known as Negro League star Dave Brown, died on May 24, 1985, in a Los Angeles-area hospital. His death certificate indicates that he had been ill with heart disease for 10 years, and his causes of death were listed as cardiac arrest and acute myocardial infarction. Brown was buried in Angelus Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Toya Rico, Alfred (Dave) Brown’s granddaughter, wrote of Alfred and Faye, “When they lived in San Francisco, we visited often. When they moved to Spokane, Washington, we visited every summer. They were the most loving and kind grandparents. I only learned that Alfred was in the Negro Leagues in a passing conversation with my father (after Grandpa died) that I thought was an exaggeration, because he was quite the embellisher.”88 Her portrayal of Brown aligns with descriptions Riley gleaned from some of Brown’s teammates, who said he was a “kind, wonderful fellow” and that he was “jolly” and “joking all the time.”89

It seems that history and historians owe Dave Brown an apology. After a closer look at the accusations made by Foster, the varied descriptions and unusual circumstances of the Adair shooting, and the facts of the Greensboro Dave Brown case, it appears unlikely that Dave Brown the ballplayer was guilty of committing any of those crimes. Instead, his reinvention as Alfred Brown provides a true reflection of the nature of the man: someone who took in two traumatized children and raised them as his own and who was, in Toya Rico’s words, “loving and kind.”

Acknowledgments

The true story of Dave Brown’s metamorphosis into Alfred Brown might never have come to light were it not for the curiosity and research acumen of SABR member Richard Bogovich. We had collaborated previously to find the story of Carl Howard, who pitched briefly for the 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords, as Richard was writing Howard’s biography for Pride of Smoketown. However, the discovery of Dave Brown’s second life as Alfred Brown generated far more excitement for both of us.

Richard had become intrigued by Brown’s story after reading the initial version of his biography that I had written for The First Negro League Champion: The 1920 Chicago American Giants. The old maxim that “two heads are better than one” was proved to be true as we built upon each other’s research. I had traced Felix Brown’s entire life, thinking that perhaps Dave had moved west after 1938 to be near his brother, but I had not bothered to look up Felix’s obituary. Richard took that extra step and found the name of the nonexistent brother, Alfred, listed as a surviving relative. Richard stated that it did not occur to him to look for a World War II draft registration card for Alfred Brown, but I did so. Upon finding the document, we discovered that the signature for the name “Brown” looked quite similar on Alfred’s WWII registration and Dave’s WWI cards. The fact that Alfred’s birth month and date were identical to Dave’s, though the year was different, aroused additional excitement. Alfred claimed to have been born in Chicago, where Dave found baseball stardom, but no Alfred B. Brown born there in 1901, or 1902, could be found in any records.

Gradually, Richard and I were able to put the pieces together, and we located two of Brown’s grandchildren, whom we then contacted. Brown’s grandson, Andre Rico, sent us a photo that confirmed Alfred to have been Dave – it was a well-known photo of the pitcher in the uniform of the Cuban Winter League’s Santa Clara Leopardes. Alfred Brown’s death certificate still gives the false birth year of 1901 and false birthplace of Chicago, but his parents’ names are the same as Dave’s and their birthplace is correctly listed as Texas. Thus, we are certain that Alfred and Dave were one and the same person.

The complete story of our efforts to solve the long-standing mystery of what happened to Dave Brown, as well as the rehabilitation of his falsely maligned reputation, will be related in detail in a separate article.

This biography was fact-checked by Carl Riechers and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

Except where otherwise indicated, all player statistics and team records were taken from Seamheads.com.

Ancestry.com was consulted for US Census information, military records, and birth and death records, except for Alfred Brown’s death certificate, which was obtained from the state of California.

Notes

1 Multiple sources list Dave Brown’s place of birth as San Marcos, Texas; however, that was the birthplace of catcher Jim Brown. There is no evidence that the two players were related; even if they were kin, they certainly were not members of the same immediate family.

2 Silas Brown is listed as “Cyrus” in the 1900 census, but this appears to be a census-taker’s error that was typical of that time. Dave gave his father’s name as “Silas” on his 1918 World War I draft registration card, and Felix Brown gave the initials “S.B.” – with “S.” presumably standing for “Silas” – when he provided family information for their brother Webster’s death certificate.

3 “Arkansas Negroes Clean Up on Dallas,” Fort Worth Record, June 7, 1917: 7. Since the two players had the same last name, their positions were sometimes listed incorrectly in newspaper lineups or line scores. The error is readily apparent because while a catcher might pitch in an emergency if he were able to do so, it is extremely doubtful that any team in any era would risk an injury to a star pitcher by having him catch. (As Negro Leagues fans are likely already aware, there was one notable exception to this rule in the person of Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, who earned his nickname by sometimes pitching one game of a doubleheader and then catching the second game.)

4 “Dallas Black Giants Win Game in Twelfth,” Fort Worth Record, June 15, 1917: 11.

5 J. Alba Austin, “Dallas Black Giants Take 2 from Camp Travis Nine,” Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition), May 25, 1918: 9.

6 “Plenty of Baseball Provided for Fans of Dallas Today,” Dallas Morning News, August 11, 1918.

7 “American Giants Open Sunday: ‘Rube’ Foster Will Present the Greatest Team of his Career,” Chicago Defender, April 12, 1919: 11.

8 “League Moguls Here This Week; Baseball War Looms,” Chicago Defender, March 17, 1923: 10. Foster’s allegations became rumors that were widespread enough to be included in different works by noted Negro League historians James A. Riley and John B. Holway; however, no evidence has ever been offered to substantiate the story. In fact, Foster’s initial tale took on additional uncertainty, with Riley even stating that the highway robbery incident involving Brown occurred in the year 1917; see James A. Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons: Essays on Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012), 71. Riley’s claim contradicts Foster’s assertion that the incident occurred after Brown had first pitched for the Chicago American Giants in 1919 and demonstrates how the story took on a life of its own beyond the initial news article in the Defender.

9 “League Moguls Here This Week; Baseball War Looms.”

10 Foster would not have had to pay $20,000 for the bond; however, even the standard 10 percent of that figure is $2,000, which would have been an exorbitant sum for Foster to pay for a pitcher he claimed had not yet proved himself. Another problem with Foster’s story involves the terminology used. Foster claimed that he paid a bond to have Brown paroled to him; however, these two things do not go together. A bond is paid so that an accused person who is being released from jail will show up in court for his hearing and/or trial, whereas parole is granted to a person who has already been convicted and has been serving time in prison. Thus, if Foster truly paid money to have Brown released from prison – an action that seems highly doubtful – he may have managed to bribe prison officials rather than to follow any legal procedures.

11 “Desperado Is Slain in Fight with Cops,” Tampa Bay Times, March 14, 1919: 3.

12 “Negro Killed after Long Chase by Officers,” Dallas Morning News, February 1, 1919: 5.

13 “Negro Killed after Long Chase by Officers.”

14 The other major independent teams in the West in 1919 were the Detroit Stars, Cuban Stars West, St. Louis Giants, Dayton Marcos, Jewell’s ABCs, and the Chicago Giants.

15 “Foster Giants, With Two Hits, Nip Kenosha, 5-0,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1919: 19.

16 Except for the Jewell’s ABCs, all the major Western Independent Clubs from 1919 became members of the NNL in 1920; two additional squads – the Indianapolis ABCs and the Kansas City Monarchs – also were founding members of the circuit.

17 Captain James H. Smith, “Foster’s Crew Puts Kibosh on Chicago Giants,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1920: 9.

18 “American Giants, 2; Knoxville, 1,” Chicago Defender, October 9, 1920: 6; Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons, 74.

19 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007), 80.

20 Chicago’s 4-3-1 record against the Bacharach Giants was derived from the game accounts found in Bill Nowlin’s timeline for the 1920 American Giants in Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin, eds., The First Negro League Champion: The 1920 Chicago American Giants (Phoenix: SABR, 2022).

21 “Pitchers’ Battle Goes to Dave Brown, 1-0,” Chicago Defender, August 20, 1921: 10.

22 “Pitchers’ Battle Goes to Dave Brown, 1-0.”

23 Frank Young, “It’s All in the Game: The Montgomery Grey Sox-American Giants Game,” Chicago Defender, September 17, 1921: 10.

24 Debono, 85; “Chicago American Giants Beat Hilldale Team 5-2,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, October 11, 1921: 7.

25 Debono, 85.

26 “Near-Riot Stops Baseball Game,” Chicago Defender, May 13, 1922: 1.

27 Mister Fan, “American Giants Find K.C. Monarchs a Tough Bunch,” Chicago Defender, May 13, 1922: 10.

28 “American Giants Find K.C. Monarchs a Tough Bunch.”

29 “American Giants Find K.C. Monarchs a Tough Bunch.”

30 “Near-Riot Stops Baseball Game.”

31 Debono, 90.

32 “The Game Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1922: 10.

33 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 143.

34 Figueredo, 147.

35 The founding teams of the Eastern Colored League were Hilldale, the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, the Cuban Stars East, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the New York Lincoln Giants, and the Baltimore Black Sox.

36 “Pitchers Brown and Rile Jump to the Outlaws,” Chicago Defender, February 17, 1923: 10.

37 “Pitchers Brown and Rile Jump to the Outlaws.”

38 “League Moguls Here This Week; Baseball War Looms.”

39 Figueredo, 148.

40 Figueredo, 154.

41 “Lincoln Giants Grab Two Games from Washington,” Chicago Defender, May 24, 1924: 9. The Harrisburg Giants were the other new addition to the ECL in 1924.

42 “Lincoln Giants Outclass Bacharach Giants in Two Games and Lead League,” Chicago Defender, May 31, 1924: 9.

43 “Cubans Win Two Games from the Lincolns,” Chicago Defender, October 4, 1924: 9.

44 Figueredo, 157.

45 Figueredo, 157-58, 160.

46 “Lincolns Win Two from Bacharach Giants,” Delaware County Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), April 28, 1925: 8.

47 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 118. The claim was repeated in Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons, 73.

48 “Man Shot Dead by Enemy in Street,” New York Evening Journal, April 28, 1925: 12.

49 “Shot Entering His Home/Man Is Instantly Killed – Assailant Escapes,” New York Evening Post, April 28, 1925: 2.

50 “Extra: Kill Man and Escape in Taxi,” New York Amsterdam News, April 29, 1925: 1.

51 “Gunmen Shoot Down Man at His Doorstep: Cops Comb City for Slayers,” Chicago Defender, May 2, 1925: 4.

52 “Gunmen Shoot Down Man at His Doorstep: Cops Comb City for Slayers.”

53 “Man Shot Down in Street; Dies in Hospital,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 2, 1925: 1.

54 “Local Baseball Players Alleged to Be Mixed in Shooting of Benj. Adair,” New York Age, May 2, 1925: 1.

55 “Taxi Driver Freed in Adair Murder,” New York Amsterdam News, May 6, 1925: 2.

56 “Police Unable to Find Ballplayers,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 16, 1925: 6.

57 “Police Unable to Find Ballplayers.”

58 “Lincoln Giants Get Rid of Marcel [sic] in Trade with Bacharach Giants, Getting Three Hurlers for the ‘Stormy Petrel,’” New York Age, May 16, 1925: 6.

59 “Oliver Marcel [sic] Back with Lincoln Giants,” New York Age, June 20, 1925: 6.

60 “Frank Wickware, Pitcher, Is Freed in Murder Case,” Chicago Defender, May 23, 1925: 9.

61 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 9, 1925: 13.

62 “Colored Boys Run Wild to Win, 11 to 4,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, June 21, 1926: 14.

63 “Union Giants Hurler Whiffs 17 at Spencer,” Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette, July 10, 1926: 9.

64 “LeMars Loses to Pipestone by 7-2 Score,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, July 31, 1926: 15.

65 Peter W. Gorton, “The Mystery of Lefty Wilson” in Steven R. Hoffbeck, ed., Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 108-111.

66 Gorton in Hoffbeck, 110.

67 Gorton in Hoffbeck, 110.

68 “Donaldson and Wilson to Be Opposing Pitchers,” Brainerd (Minnesota) Daily Dispatch, June 14, 1928: 5.

69 Riley, Of Monarchs and Black Barons, 73-74; John Maher, “A Tale of Baseball, Murder, Mystery,” Austin American-Statesman, August 25, 1997: 15, 22.

70 Gorton in Hoffbeck, 110-11.

71 “S.C. Firm Will Back Fast Club,” Sioux City Journal, April 14, 1929: 21.

72 Joe Ryan, “Keri-Keen Wins from Kary-All,” Sioux City Journal, May 12, 1929: 21.

73 “Cubans Drop Final Tilt 5-4,” Saskatoon (Saskatchewan) Star-Phoenix, August 30, 1929: 21.

74 “Colored Davids Down Springers by 8 to 6 Count,” St. Cloud (Minnesota) Times, June 23, 1930: 13.

75 “Bewhiskered Colored Team Invades Copeland Today,” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, August 30, 1931: 9.

76 “Fineis Giants Split Two with Davidites,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, August 5, 1932: 18.

77 “Jess Wells Injured and Negro Is Held,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, July 16, 1938: 4. Subsequent articles in both Greensboro newspapers always gave the victim’s first name as Jack, which appears to have been his correct name.

78 “Negro May Be Involved in 13-Year-Old Murder,” Greensboro Record, July 23, 1938: 10. This article erroneously gave Brown’s first name as George.

79 “Negro May Be Involved in 13-Year-Old Murder.”

80 “Lucky,” Raleigh News and Observer, July 31, 1938: 6.

81 “Dave Brown, Charged with Murder, Waives Extradition/Was Arrested Here on Robbery Charge,” Greensboro Daily News, July 24, 1938: 19.

82 “Expect Word Today from New Yorkers About Dave Brown,” Greensboro Daily News, July 25, 1938: 14.

83 “Filipino Trio Dies; Slayer Ends Own Life,” Marysville (California) Appeal-Democrat, February 8, 1937: 1-2.

84 “Echoes of Slaying Heard in Appeal,” Marysville Appeal-Democrat, March 25, 1937: 7.

85 Toya Rico, Terry Rico’s daughter and Alfred/Dave Brown’s granddaughter, provided this information in an April 12, 2023, Instagram correspondence with Richard Bogovich.

86 “Brown, Faye L.,” Spokane Chronicle, November 11, 1981: 27.

87 “Obituaries: Eva L. Sims,” Fresno Bee, July 29, 1983: B3.

88 Toya Rico message to Richard Bogovich via Instagram, April 12, 2023.

89 Riley, Biographical Encyclopedia, 117.

Full Name

Dave K. Brown

Born

June 9, 1897 at Marquez, TX (USA)

Died

May 24, 1985 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.