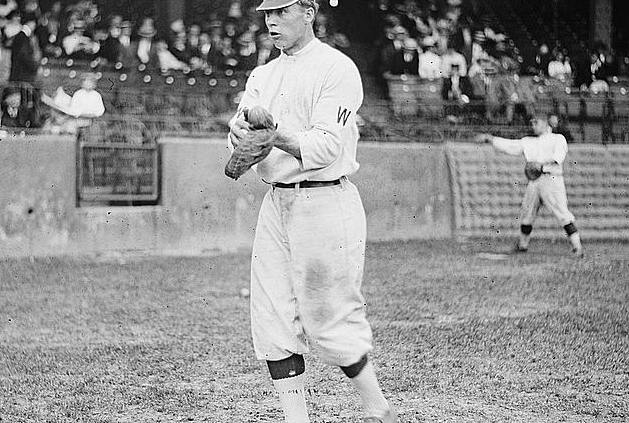

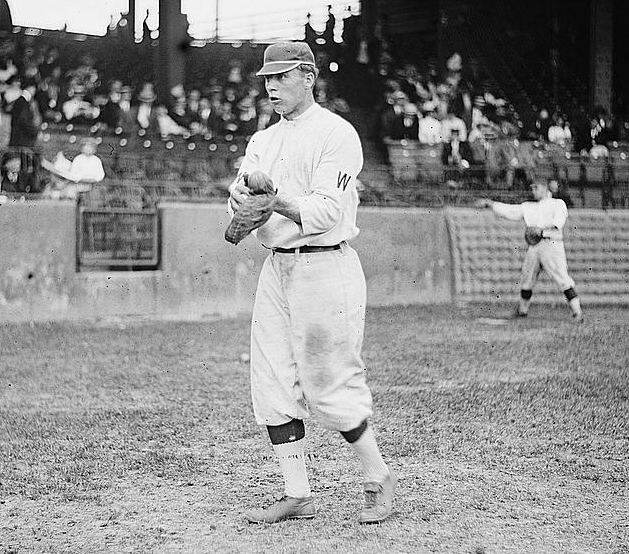

Eddie Ainsmith

Eddie Ainsmith punched above his weight – both in terms of the accolades he received during and after his playing days as a light-hitting backstop who never appeared in the postseason…and as a fierce fighter. His career raises the question of how much credit a player should get for partnering with a legend of the game. In this case, that legend was Walter Johnson, whom Ainsmith handled from 1910 through 1918, the first nine of his 15 years in the majors.

Eddie Ainsmith punched above his weight – both in terms of the accolades he received during and after his playing days as a light-hitting backstop who never appeared in the postseason…and as a fierce fighter. His career raises the question of how much credit a player should get for partnering with a legend of the game. In this case, that legend was Walter Johnson, whom Ainsmith handled from 1910 through 1918, the first nine of his 15 years in the majors.

Ainsmith’s parents were both born in Russia, the father in the mid-1840s and the mother in 1855. They sailed from Bremen, Germany, to New York in June 1894. The family also went by the last name of Ainsworth (the un-Anglicized surname is not known). William, a shoemaker,1 and Hannah, who also went by Anna, raised three sons. Eddie Ainsmith, the middle son, was born on February 4, 1890, in Russia but grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“Until 1905, Ainsmith was an outfielder. The following year he began to catch for a semipro team.”2 Ainsmith “attracted attention of scouts while … playing with the Holy Name Society team in Cambridge,”3 although he went to high school at Colby Academy in New London, New Hampshire.4

After stints in Toronto and Jersey City in the Eastern League, he played three seasons in the New England League for two Massachusetts teams located in nearby cities: namely, Lawrence and Lowell. Ainsmith battled arbiters, ballplayers, fans, and strangers. With Lawrence, he served an “indefinite suspension on account of … trouble with an umpire.” 5

The scant statistical record from Ainsmith’s 1909 and 1910 seasons shows that he batted .240. Washington signed the catcher, whom one report mischaracterized before he played in the American League as “some batsmith … said to train in the .300 class.”6

This evaluation of his offensive prowess was greatly exaggerated, but Ainsmith’s troubles with authority figures in the minors proved portentous. He did not immediately report to Washington because of “a mix-up with [Lawrence] Manager [Jimmy] Bannon, [who] announced that Ainsmith will neither be allowed to play again [in 1910] nor to join Washington until the New England League season’s close.”7

Ainsmith’s apology and a payment of at least $2,500 got the suspension lifted.8 He debuted on August 9, 1910, in the first game of a doubleheader against a formidable foe, albeit one past his peak: Cy Young, then aged 43. Ainsmith tripled for his first hit; he also made an error as Cleveland stole five bases, including two by Nap Lajoie. A game recap nevertheless noted his powerful arm, reporting that he must have “been winning prizes … for putting the shot and hurling the discus.”9

During his first home game, “in the first inning, he threw out Ty Cobb trying to steal and in the second cracked out a hit, scoring the first Washington run.”10 The following day, Ainsmith threw out all six Tigers who tried to steal and had three hits.11 “Three times Ty tried to play horse with him on the bases, and in every instance Ty was nipped.”12

Jimmy McAleer, who managed Ainsmith in 1910 and 1911, lauded his young catcher. “Sometimes that boy makes me think more of ‘Buck’ Ewing as far as his throwing is concerned,” said McAleer one day. 13

After almost one month as teammates, Ainsworth, as a defensive replacement, on September 7 caught Walter Johnson for the first time. “Johnson slacked his speed when Ainsmith went in, pitching a game entirely different from that he had shown while [Henry] Beck[endorf] was working. He did not know how Ainsmith would handle him. The younger catcher seemed fully competent.”14 After this promising start, Ainsmith was “elected to handle Johnson [in 1911] … in practically all his games, if they work together as well as they did last fall.”15

Johnson made 666 starts in his career; Ainsmith caught 210, one and one-half times more than any other receiver (Muddy Ruel had 139). Of Johnson’s 110 shutouts, Ainsmith again far outpaced the field by catching 48 (Gabby Street followed with 17).16

One month into his career, Ainsmith had held his own with Johnson and against Cobb and Lajoie, three American League giants. A Boston Globe account quoted Philadelphia manager Connie Mack, whose team won its first World Series in 1910. It described Ainsmith as “one of the sweetest in the business. ‘I don’t understand,’ [Mack] adds, ‘how the young fellow escaped my scouts last season.’”17

This praise notwithstanding, Ainsmith’s time in Washington was stagnant offensively – his production never approached league average:

- 1910: 53 OPS+

- 1911: 55

- 1912: 61

- 1913: 60

- 1914: 60

- 1915: 58

- 1916: 33

- 1917: 66

- 1918: 80

- Average: 62 OPS+

In 1911, Ainsmith hurt his ankle in May and missed about 10 days.18 He then got spiked in June, which kept him out another 20 days.19

In 1912, Ainsmith had an opportunity to catch a plurality of games for the first time after Washington traded Street, but confessed, “I ought to be glad and yet I’m sad. The trade … sends away a great catcher, and a grand fellow… At the same time, his departure gives me a better chance to show.”20

Ainsmith had an uneven season. In August, “he took one of Johnson’s fast pitches on the bare hand.”21 Fortunately, he missed only a few days.

In early September, a banquet in his honor took place when Washington visited Boston. Johnson, manager Clark Griffith, and Cambridge Mayor J. Edward Barry attended the soirée, which attracted 200 people. Ainsmith “could say but little. ‘My heart is bubbling over with deep feelings for the friends at home. This has left a deep impression upon me. It is the happiest moment of my career. I thank you,’ he said.”22

The next day, Ainsmith caught Johnson in an arranged showdown between the Big Train (28-11) and Smoky Joe Wood (29-4). Earlier in the season, Johnson had set the AL record with 16 straight wins; Wood took the mound with an extant streak of 13. Ainsmith fanned twice, walked once, and sacrificed. He threw out Tris Speaker, the only runner who attempted a steal. Johnson yielded five hits, one walk, and one run. Ainsmith came up with two outs in the ninth with a runner on second. With the chance to play the hero in a city next to his hometown, he struck out swinging as Washington lost 1-0.

Ainsmith did not appear in a game after the memorable September 6 contest. After the Boston game, he “sat in a draft, and … his neck was stiff and his back sore.”23 He ended up in Georgetown University Hospital for a few weeks.24 Thus, he revamped his offseason workout schedule. Rather than playing basketball in Cambridge, he went to Texas.25

Ainsmith’s offseason profoundly changed his personal life. “I am in the pink of condition now,” he said. “I have been living in the open … and regained my strength by roaming … in search of game … I had a pack mule and a horse… I killed most of my food, and … not with a stone either.”26

Even so, in 1913, he had another poor year at the plate. After the season, Lajoie observed, “Ainsmith couldn’t hit a low ball with a shovel, but he would probably bat .400 if served balls around his shoulders continually.”27

His struggles on offense notwithstanding, Ainsmith supported Johnson as the ace had his best year, going 36-7 with a 1.14 ERA.28 After Johnson beat the defending world champion Red Sox on July 3 in a 1-0, 15-inning battle in Boston, Ainsmith observed, “I have never seen Walter hop through them as he did … When he struck out [Larry] Gardner, it was practically impossible to follow the ball…. His speed was so great that one of the balls … struck me on the chest directly over the heart. It came near knocking me out.”29

Ainsmith showed his own speed in 1913 as well, leading teammate Ray Morgan to nickname him Deerfoot.30 After notching nine steals in his first 155 games over three years, he set a career high with 17 in 84 games. The mark set an American League record for a catcher, albeit one that did not last long — both Ray Schalk31 (24) and Ed Sweeney (19) bettered it in 1914. Ainsmith’s 86 steals rank seventh among Deadball Era backstops.32

On January 2, 1914, Ainsmith married Julia Pauline Bate, “a popular young society girl of [San Antonio]. She has known Ainsmith but two years, meeting him during … 1912 when he was down [in Texas] in search of health.”33

Domestic bliss did not soothe his temper in 1914. Calling balls and strikes in an exhibition game against the Braves, he clashed with the irascible Johnny Evers. Following the contest, Evers refused to apologize to Ainsmith and then, sensibly, declined to fight someone two inches taller and 55 pounds heavier. Instead, Boston first baseman Charles Schmidt, four inches taller and 15 pounds heavier than Ainsmith, “was bold enough to accept the challenge, throwing in a few uncomplimentary remarks as emphasis. Ainsmith made for him, grabbing him by the throat and sending a stiff blow to his jaw.”34

Evers won the 1914 NL Chalmers Award (while setting a career high in ejections) in his last championship campaign.35 Schmidt had his best season. By contrast, Ainsmith struggled again. A broken bone in his wrist cost him more than one month of the 1914 season.36 Less than two months after returning, on July 30 he bumped umpire Jack Sheridan, who ejected the player. After a fan yelled at Ainsmith, he “jumped into the stand and blows were exchanged. Catcher [John] Henry attempted to pull Ainsmith from the stand and a chair thrown … struck Henry on the head. The crowd … rushed on the field.”37 The Washington Post’s Stanley T. Milliken both blamed and partially exonerated Ainsmith, noting that a fan “called Ainsmith a name that no one with any courage will stand for … Ainsmith … was at fault, yet there are times when one loses his head in cases of this kind.”38

American League President Ban Johnson called Ainsmith “cowardly” and suspended him. 39 Griffith stood by his player, at least somewhat, saying, “Ainsmith … is a hotheaded fellow, who lost control of himself… he did wrong, but his action was not half so bad as many … believe.”40 Ainsmith missed a fortnight of games after the fight.

Julia gave birth to Ann Katherine on January 27, 1915. “She’s going to be great company for her mother when I’m on the road,” Ainsmith told [The Post]. “She sure is a great kid, and I’m the proudest and happiest man in Washington.”41

Fatherhood, too, failed to soften Ainsmith: days into the 1915 season, he received an assault charge and a sentence of 30 days in jail after an encounter with a stranger. Ainsmith appealed and paid $300 bail for his freedom.42 He escaped with a $50 fine, probation for a year, and a judicial lecture: “You have got to stop picking quarrels,” [the judge] said to the able mitt artist, “because such conduct will not meet with leniency in the future. The assault was unprovoked, vicious in its tendencies, and to some extent cruel.”43

Ainsmith missed the first eight games of 1916 after suffering “eye trouble for several months.”44 Despite his pugilistic personality and poor production at the plate, he remained admired. A writeup after his 1916 debut declared, “Ainsmith showed … his old-time skill, which makes him one of the greatest backstops of all times.”45

Straining to see, Ainsmith slugged a career-worst .210 in 1916. Yet he confidently predicted his walk-off extra-base hit in the 12th inning of a July 22 game against the White Sox: “‘I am going to win this ball game for you, Grif.’ These were the words of … Ainsmith as he left the dugout… Just where the Nationals’ catcher got his hunch is not known, but he … caught one of [Reb] Russell’s curves and sent it to left center. [Patsy] Gharrity was on first at the time with one down. He scored.”46

Ainsmith suffered another finger injury about one month later.47 As a result, he played just once from August 24 through October 1.

Poor vision still hampered Ainsmith in 1917.48 Nevertheless, he served as the lone observer of “what writer Joe Williams dubbed ‘the Louis-Schmeling fight of baseball….’ After [a spring training] game, [Buck] Herzog challenged Cobb to a fight. They met in Cobb’s hotel room, with … only Eddie Ainsmith present as the third man.”49

Ainsmith’s final Washington campaign proved unexpectedly challenging. On July 4, he mourned his wife, who died at the tender age of 23 “after a long illness.”50 Eddie would later marry Loretta Brady.

One week after Julia’s death, the District of Columbia ordered Ainsmith to quit baseball and either engage in a useful occupation related to the World War I effort or enter the military draft.51 An appeal to Secretary of War Newton Baker sought to keep players from having to comply.52 Baker rejected the argument and deemed baseball a non-essential occupation.53 Rather than ending the season in mid-July, as first feared, baseball truncated its schedule by about a month but still played the full World Series.

Ainsmith went to Baltimore for the offseason and worked as a ship builder.54 His older brother Frederick, born on May 25, 1888, was wounded while serving in the U.S. Army.55 They also had a brother named Fritz, born in 1892, who built pianos.56

In 1918, Ainsmith had slugged more than .300 for the first time in his career and edged closer to average offensive production. Even so, on January 17, 1919, Washington traded him, “in part because of negative fan reaction … to what was seen by some as a reluctance to do his patriotic duty.”57 Ainsmith went to Detroit as part of a three-way deal also involving Boston. He spent parts of three seasons with the Tigers and blossomed at first; in 1919 he set career highs in plate appearances (422), triples (12), walks (45), on base percentage (.354), and OPS+ (115).

Before the trade, Washington had 17 more wins than Detroit in 1918; in 1919, Detroit had 24 more wins than Washington. The Nationals gave up on infielder Hal Janvrin, the key player they received in the trade, by shipping him to Buffalo of the International League on August 25, 1919.

Over the medium term, the trade worked out wonderfully for Washington because Buffalo exchanged Bucky Harris for Janvrin. In 1922 and 1923, Harris received MVP votes. As a player-manager, Harris took the 1924 Senators to a World Series title and the 1925 team to the AL pennant. In 1975, he won induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In the short term, “Ainsmith was one of the main cogs in the Michigan machine” in 1919.58 In 1920, though, his production on offense was akin to his first six undistinguished Washington campaigns. He improved in 1921, but the Tigers released the 31-year-old catcher on July 25. Ainsmith had served as a bridge between Detroit backstops Oscar Stanage (1909-1920) and Johnny Bassler (1921-1927).

Ainsmith ended up with the Cardinals to back up Verne Clemons, who batted .320. In 1922, however, Clemons struggled, posting an Ainsmith-like 63 OPS+ and dealing with a hand injury.59 Ainsmith capitalized on this opportunity for increased playing time: he established career highs in at-bats (379), runs (46), and hits (111). Surprisingly, he hit 13 homers – the lion’s share of his 22 in the majors. Other personal bests included his marks in RBIs (59), batting average (.293), slugging percentage (.454), and OPS (.797).

Ainsmith played his typical tough defense. Facing Brooklyn, he “blocked Hank De Berry [sic] off the plate in the third inning before receiving the ball … Ainsmith was standing with his right foot on the pan and his left leg toward third base, leaving no opening for De Berry, who did not care to crash into him … Ainsmith received the throw … ran back and tagged De Berry, who had passed the plate.”60

More than two decades later, Ainsmith worked with DeBerry; more than five decades later, Ainsmith called his St. Louis teammate Rogers Hornsby “the greatest to ever play the game.”61

In 1923, Ainsmith regressed. Up until September 1, he did most of the catching but produced less than both Clemons and Harry McCurdy. Two days later, the Cards released him after a “run-in” with manager Branch Rickey.62 The imbroglio continued after the season ended, when Ainsmith petitioned Commissioner Landis for pay withheld by the teetotaling Rickey. The controversy made the front page of The Sporting News. Ainsmith argued, “I want … the money I earned by catching nearly all the games played until Rickey fired me. Do I look like a drunkard? And say, does my record look like I was?”63

Ainsmith had cups of coffee with Brooklyn in 1923 and the Giants in 1924; John McGraw may have answered Ainsmith’s question from the prior season when New York released him on August 20. “Law and order will prevail … or I will dispose of the players who refuse to obey,” said McGraw. “I must win pennants. That’s my job in baseball…. I must have discipline… Each ball player … must refrain from temptations that all good or well-trained athletes keep away from.”64

Long after his career, Ainsmith recalled imbibing with three future Hall of Famers: Harry Heilmann, Babe Ruth, and Bob Meusel. “One night we took the two of them to one of the big breweries in town …” said Ainsmith. “We got back to the hotel in the wee hours of the morning. About 7 a.m., Ruth calls me … and says he wants to go back. Heilmann gets the idea that maybe if we took him back and filled him up some more, he might not be able to play that afternoon…. Ruth showed up … and hit two of the hardest home runs I have ever seen.”65

Ainsmith played for seven minor-league teams in six years from 1925-1930 but maintained a major-league temper. In the Minneapolis 1925 home opener, future NFL Hall of Famer Joe Guyon of Louisville clashed with Johnny Butler of the Millers. “It wasn’t Ainsmith’s fight to start with … Eddie made it his fight … and it was still Edward’s battle at the finish for after mauling Guyon on the field, the Miller catcher followed Guyon under the grandstand and walloped [him] until Josephus conceded defeat.”66

Ainsmith led baseball tours of Japan after the 1924 and 1925 season. Female players made up most of the second team, although Ainsmith and Earl Hamilton, who pitched in 410 games in the majors, formed the battery. As recounted by Barbara Gregorich, the trip ran into financial troubles. Ainsmith came up with sufficient funds so that he and his wife could return home, but he abandoned three of the young female athletes. Their families wired money weeks later, but 16-year-old Leona Kearns washed overboard on the ship home. Ainsmith never publicly discussed his role in the tragedy. Gregorich concluded her damning account thus: “If he ever reflected that he spent his life catching a baseball but dropped the most important pitch, he never told a soul.”67

Ainsmith stayed in the game. Even as an umpire he sought conflict. After a contentions 1936 contest concluded, he “became engaged … with fans… Eddie would stick his chin up close to the fan and then jerk it back as the fellow would swing…. In the meantime fans … swarmed around Ainsmith … Finally … police arrived and broke up the near-riot.”68 Still, the nonpareil Shirley Povich of The Washington Post reported after that season that “Ainsmith will be the next new American League umpire … Ainsmith is regarded as the best umpire in the Southern Association on balls and strikes.”69 Povich subsequently wrote, however, “Umpire In Chief Tommy Connolly scouted [Ainsmith’s] work in the Southern Association … and found his umpiring to be listless.”70

Ainsmith found his way back to the majors by scouting for the Giants. He and DeBerry covered the Middle Atlantic region.71 Seeing Sal Maglie, Ainsmith opined, “He hasn’t much of a curve, but he could develop.”72 He was right: New York signed Maglie, and on the strength of his biting curve, the twirler went 95-42 in seven seasons for the Giants.

Ainsmith served as a pallbearer at Johnson’s funeral in 1946.73 The next year, he managed the Rockford Peaches of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. In 1948, he opened the New York School of Baseball, which offered a three-week summer program.74

Loretta Ainsmith, Eddie’s second wife, died on January 10, 1971. Ainsmith’s parents lived long lives. Anna passed in 1936 at the age of about 80, and William four years later at about 95. Longevity ran in the family: Eddie died on September 6, 1981, at the age of 91. His daughter Ann surpassed them all – she was 106 when she died in 2021.

Griffith, Ainsmith’s longtime skipper, praised him highly: “[Bill] Dickey and [Mickey] Cochrane and a lot of other catchers could outhit Ainsmith, but none … could compare with him around the plate. He’d throw out base runners … from his squatting position, or drawing his arm back, and … was unquestionably the fastest catcher in history. And as a plate blocker Ainsmith was great.”75

In 1932, a longtime Washington trainer named Ainsmith the best catcher in team history.76 In 1954, the Washington Chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association voted Ainsmith the second-best Washington catcher behind Ruel but ahead of Rick Ferrell and Luke Sewell.77

Modern statistical analysis makes these rankings appear dubious. For the time they spent in Washington only, Ferrell’s 9.5 WAR in eight seasons far exceeds Ainsmith’s 2.4 in nine campaigns; Sewell’s 1.8 in two years is more than three times Ainsmith’s per annum total. Yet a Walter Johnson biographer called Ainsmith “badly underrated by those whose opinions are formed entirely by statistical tabulations.”78 Maybe he has received insufficient credit for his impressive baserunning, plate-blocking, and throwing skills. Lack of offense matters, too. On balance, however, Johnson’s ability to dominate with Ainsmith behind the plate highlighted the strengths and shadowed the weaknesses of the catcher’s checkered career.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credit: Eddie Ainsmith, Library of Congress.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 The Cambridge Directory, 1916: 317.

2 Stanley T. Milliken, “Only Five of Nationals’ Players with Club for an Extended Time,” The Washington Post, March 8, 1914: 8.

3 Thomas Kirby, “Figure Only Athletics in Battle for Pennant,” The Washington Post, May 18, 1913: S4.

4 Ford Sawyer, “New Englanders in the Big Leagues,” The Boston Globe, May 29, 1923: 16. Ainsmith scored eight touchdowns in a football game against Kimball Union Academy

5 “Lowell 12, Lawrence 11,” The Boston Globe, May 25, 1910: 6.

6 Paul W. Eaton, “From the Capital,” The Sporting Life, June 18, 1910: 5.

7 “Ainsmith in Bad with Manager; Won’t Let Him Join Washington,” The Washington Post, July 31, 1910: M6.

8 “Delivered to McAleer,” The Boston Globe, August 9, 1910: 7. Another article gives a higher price. “Scout [Mike] Kahoe bought his release from Lawrence for $3800” according to Kirby, “Figure Only Athletics in Battle for Pennant.” Kahoe employed subterfuge to snatch Ainsmith from Pittsburgh. William Peet, “Story of How Kahoe Landed Ainsmith Reads Like a Novel,” The Washington Herald, September 22, 1910: 8.

9 “Nationals Get Even Break in First Cleveland Joust,” The Washington Post, August 10, 1910: 4. The description sounds figurative, but months before this article appeared Ainsmith finished third in a shotput competition with a throw of 38 feet and 11 inches. The Dartmouth, May 17, 1910: 659.

10 “Detroit 8, Washington 3,” The Boston Globe, August 17, 1910: 7. Ainsmith did not score but drove in a run with his hit.

11 “Detroit 4, Washington 2,” The Boston Globe, August 18, 1910: 6.

12 Paul W. Eaton, “From the Capital,” The Sporting Life, August 27, 1910: 7.

13 Untitled and undated clipping from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s file on Ainsmith. Thanks to Hall Reference Librarian Rachel Wells for scanning the file.

14 “Noted of the Nationals,” The Washington Post, September 8, 1910: 8.

15 Joe S. Jackson, “Johnson to the Fore,” The Washington Post, April 15, 1911: 8.

16 Walt Wilson, “Catching Hall of Fame Pitchers: Walter Johnson’s Battery Mates,” batteries.sabr.org/7068.htm (accessed July 9, 2024).

17 “Baseball Notes,” The Boston Globe, September 9, 1910: 6.

18 “Naps Make Five after Chance to Retire Side,” The Washington Post, May 21, 1911: S1.

19 “Highlanders Batter All Pitchers, Downing Nationals in Both Games,” The Washington Post, June 25, 1911: S1.

20 Joe S. Jackson, “Ainsmith First here,” The Washington Post, February 29, 1912: 9.

21 “Williams Only Sound Catcher,” The Washington Post, August 12, 1912: 6.

22 “Flattering Reception to Wee Wee Ainsmith,” The Cambridge Chronicle, September 7, 1912: 6.

23 Joe S. Jackson, “Nationals Find Out That Albany Fans Are Patient,” The Washington Post, September 9, 1912: 6.

24 Joe S. Jackson, “Nationals Almost Sure to Land Second Place,” The Washington Post, September 30, 1912: 8.

25 “Roughing It in Texas Cured Eddie Ainsmith,” The Boston Globe, December 11, 1912: 13.

26 Stanley T. Milliken, “Ainsmith in Town,” The Washington Post, February 25, 1913: 8.

27 Nap Lajoie, “How to Hit the Ball,” The Boston Globe, November 2, 1913: 52.

28 Ainsmith’s chatter distracted hitters. “Eddie should get all the credit for Walter Johnson’s great record. There isn’t a batter in the country who could maintain his mental pulse with the fearful clatter Eddie keeps up behind the plate.” “American League Notes,” The Sporting Life, March 13, 1915: 7.

29 Stanley T. Milliken, “Pitcher Mullin to Go to Minor League Club,” The Washington Post, July 6, 1913: S1.

30 “Nicknames Prevalent Among Ballplayers; Some of Them Are None Too Well Received,” The Washington Post, March 21, 1915: 63.

31 Schalk far outranks Ainsmith both reputationally and statistically, but sportswriters compared them. “They are ranked as the best two catchers in the league.” “Griffith Presents Baseball Outfits,” The Washington Post, August 26, 1917: 33. “Probably [Ainsmith’s] only superior as a backstop in the majors today is Schalk, of the White Sox.” J.V. Fitzgerald, “The Round-Up,” The Washington Post, February 19, 1918: 8.

32 L. Robert Davids, “Catchers as Base Stealers,” 1982 Baseball Research Journal, sabr.org/journal/article/catchers-as-base-stealers/ (accessed July 5, 2024).

33 “Ainsmith Weds Southern Belle,” The Washington Herald, January 3, 1914: 10.

34 Stanley T. Milliken, “Evers’ Vitriolic Words Resented by Ainsmith,” The Washington Post, April 12, 1914: 49.

35 Mark S. Sternman, “The Evers Ejection Record,” The Miracle Braves of 1914 (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, Inc.), 2014: 66-67.

36 Stanley T. Milliken, “Neff, Virginia Shortstop, Is Signed by Nationals,” The Washington Post, May 10, 1914: S1. By the end of 1914, Ainsmith had broken three fingers on his right hand a total of four times. “Impossible to Handle Johnson’s Delivery with Bare Hands, Is Declaration of Henry and Ainsmith, Nationals’ Catchers,” The Washington Post, March 7, 1915: 57.

37 “Morgan Struck by Umpire Sheridan,” The Boston Globe, July 31, 1914: 7.

38 Stanley T. Milliken, “Morgan Assaulted by Umpire Sheridan; Ainsmith Sends Blow to Arbiter’s Jaw, and Later Fells an Insulting Spectator,” The Washington Post, July 31, 1914: 8.

39 “Both Players Suspended,” The Boston Globe, July 31, 1914: 9.

40 Stanley T. Milliken, “Ban Johnson Hides; Silent as to Riot,” The Washington Post, August 1, 1914: 8.

41 Stanley T. Milliken, “Ainsmith Now a Daddy; ‘Stork’ Brings Him Girl,” The Washington Post, January 28, 1915: 8.

42 “Ainsmith Gets 30 Days,” The Washington Post, April 22, 1915: 9.

43 “Ainsmith Clear of Jail,” The Washington Post, April 30, 1915: 14.

44 Stanley T. Milliken, “Athletics’ Team Is Not Weak, But Not Like That of Past,” The Washington Post, April 26, 1916: 8.

45 Stanley T. Milliken, “Johnson Faces Red Sox today; Ruth Most Likely to Oppose,” The Washington Post, April 29, 1916: 8.

46 Stanley T. Milliken, “Ainsmith’s Hit Decides in the Twelfth Inning,” The Washington Post, July 23, 1916: S1.

47 Stanley T. Milliken, “Noted of Nationals,” The Washington Post, August 24, 1916: 6.

48 J.V. Fitzgerald, “The Round-Up,” The Washington Post, March 20, 1918: 10.

49 Gabriel Schechter, “Buck Herzog,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/buck-herzog/ (accessed July 9, 2024).

50 “Eddie Ainsmith’s Wife Dies,” The Washington Post, July 5, 1918: 9.

51 “Ainsmith Appeal to Be Test Case,” The Washington Post, July 12, 1918: 8.

52 “Baseball’s Fate in Baker’s Hands,” The Washington Post, July 13, 1918: 8.

53 J.V. Fitzgerald, “Baseball Players Must Work or Fight, Baker Rules, Dooming National Sport,” The Washington Post, July 20, 1918: 8.

54 J.V. Fitzgerald, “The Round-Up,” The Washington Post, September 2, 1918: 6.

55 “Wounded Slightly,” The Boston Globe, November 3, 1918: 17.

56 The Cambridge Directory, 1927: 96.

57 Bill James, The Baseball Book 1990 (New York: Willard Books, 1990), 195.

58 “Jennings on Hand to Greet Recruits,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1920: 5.

59 “Forces Bulk of Work on Eddie Ainsmith,” The Washington Post, June 29, 1922: 17.

60 “Robins Bow to Cards, 4-1,” New York Tribune, July 11, 1922: 12.

61 Bob Chick, “Lang Field: Nostalgia Revisited,” Fort Lauderdale News and Sun-Sentinel, March 18, 1972: 1C.

62 “Eddie Ainsmith Signed by McGraw,” (Brooklyn) Times Union, November 16, 1923: 18.

63 “Troubles of Eddie Make Quite a Story,” The Sporting News, December 6, 1923: 1.

64 “McGraw Swings Ax on Erring Giants,” The Boston Globe, August 21, 1924: 9.

65 Ray Boetel, “An Oldtimer Can Remember Having a Beer with Babe,” Fort Lauderdale News and Sun-Sentinel, February 8, 1976: 8D.

66 “Ainsmith’s Fistic Triumph Over Guyton Features Kels’ 10 to 1 Win,” The Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 30, 1925: 21.

67 Barbara Gregorich, “Dropping the Pitch: Leona Kearns, Eddie Ainsmith and the Philadelphia Bobbies,” The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly, 2013. Thanks to Gregorich for her email informing me that she donated her research files to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Thanks to the Hall’s Library Director Cassidy Lent for scanning two folders from the Gregorich files.

68 Bob Wilson, “Sport Talk,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 15, 1936: 10.

69 Shirley Povich, “This Morning …” The Washington Post, December 22, 1936: X23. The column title and the quotation both have ellipses.

70 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” The Washington Post, March 15, 1938: X17.

71 “Ainsmith, Now Giant Scout, Praises Hoyas’ Sophomore,” The Washington Post, April 12, 1939: 17.

72 James D. Szalontai, Close Shave: The Life and Times of Baseball’s Sal Maglie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 26.

73 Shirley Povich, The Washington Senators (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2010), 224.

74 “Eddie Ainsmith to Head Diamond School in N.Y.,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1948: 30.

75 Shirley Povich, “This Morning …” The Washington Post, January 12, 1937: 15. To Griffith’s point, Ainsmith had a career mark of .232 in more than 3,000 big-league at-bats.

76 “Martin’s All-Time, All-Star Team Picks Johnson, Harris,” The Washington Post, March 6, 1932: 13, 16.

77 “Breakdown on Washington All-Time Team Balloting,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1954: 17.

78 Jack Kavanagh, Walter Johnson: A Life (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1995), 47.

Full Name

Edward Wilbur Ainsmith

Born

February 4, 1890 at , (Russia)

Died

September 6, 1981 at Fort Lauderdale, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.