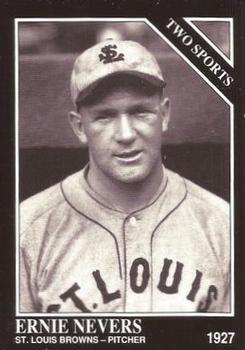

Ernie Nevers

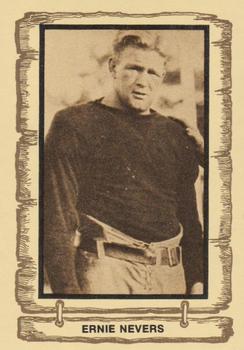

Ernie Nevers’ football career as a fullback and coach is well documented. While a full biography has yet to be written, much ink has been spilled in the telling of his gridiron glory. His baseball career has not been so well scoured in the near century since he pitched professionally. It is only natural that his football playing — he was a charter member of both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame1 — has overshadowed his more modest diamond doings.

Ernie Nevers’ football career as a fullback and coach is well documented. While a full biography has yet to be written, much ink has been spilled in the telling of his gridiron glory. His baseball career has not been so well scoured in the near century since he pitched professionally. It is only natural that his football playing — he was a charter member of both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame1 — has overshadowed his more modest diamond doings.

Ernest Alonzo Nevers was born on June 11, 1902, in Willow River, Minnesota. The youngest of seven children, he stood 6-feet and weighed 200 pounds in adulthood and batted and threw right-handed.

His parents, George Edward Nevers (1862-1933) and Mary Ann (McKenna) Nevers (1862-1937), were married in their native New Brunswick, Canada, in 1881. Their first two sons, Harry (1882-1956) and Frank (1883-1953), were born in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Two more sons, John (1887-1963) and George Charles (1888-1944), were born in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Another son, Arthur (1894-1953), was born in Hinckley, Minnesota. Their only daughter, Edith Swanson (1896-1986), was born in Willow River.

“Ernie, he was just crazy about baseball. He always carried a bat around. He wanted someone to pitch to him. He was a very friendly little boy,” recalled Willow River resident Genevieve LeBerge in 1972.2 This is likely due to having older brothers who played baseball. Typically, only last names were used, so which of the brothers being mentioned in newspaper coverage remains up for conjecture. Among the specifics, the Duluth News Tribune reported on May 26, 1908, that “John and George [C.] Nevers went to Pine City Sunday to do the battery work for the Willow River ball team.”3

(George C.’s grandson and great-grandson played in the minor leagues. The Kansas City A’s drafted John Gordon “Gordy” Nevers in 1958. Gordy’s son, Tom Nevers, was a 1990 first-round pick by the Houston Astros. Also, Edith’s husband’s sister was married to Jack Cunningham, brother of Detroit Tigers pitcher George Cunningham from Sturgeon Lake, Minnesota.)

The Nevers family, of English origin, has been traced back to Ernie’s fifth great-grandfather in Massachusetts in 1666.4 Census information shows that Mary Ann McKenna was born to an Irish father and a Canadian mother.5

George E. Nevers was an innkeeper in Wisconsin and Minnesota. His hotel in Moose Lake, Minnesota, burned in a fire on May 30, 1912.6 He rebuilt a hotel in Moose Lake, but it burned as well, in the October 12, 1918, Cloquet fire — a 250,000-acre forest fire that killed 453 and displaced 52,000 people.

In the aftermath of the first fire, Ernie’s parents moved to the Allouez neighborhood of Superior, Wisconsin, where George E. owned a saloon. Ernie Nevers went to Superior Central High School. The football team won the state title in his sophomore year but in his junior year it lost the championship game to La Crosse and its star player, Bob Fitzke. Nevers played in three state basketball tournaments with one championship.

Nevers’ parents’ relocation to the Rincon Valley region of California’s Sonoma County to operate a fruit ranch coincided with the enactment of Prohibition in 1920. In his senior year, he starred on the Santa Rosa High School football team but returned to Superior to play basketball for Central. He graduated from Central in 1921 and planned on attending the University of Wisconsin.

A letter from his father persuaded Nevers to move back to California. He went to Santa Rosa Junior College before enrolling at Stanford. In 1922 he played baseball for the junior college, the Santa Rosa Outlaws, the Sonoma State Home, and the Graton team. He then played on Stanford’s freshman sports squads in the 1922-23 school year. His baseball coaches were freshmen coach Ernest “Husky” Hunt and varsity coach Harry Wolter.

Nevers was the first player to hit a home run over the center-field fence at Stanford as his freshmen team beat Berkeley High School, 13-1, on March 10, 1923.7 He then starred for a Santa Rosa baseball club sponsored by (Walt) Nagle’s Sport Shop. His other summer baseball playing during his Stanford years included two seasons for the Guerneville Tigers. He pitched all 16 innings in Guerneville’s 1-0 win against Cotati on July 13, 1924.

Besides playing football and baseball for Stanford, Nevers threw javelin and was a two-year basketball starting forward.

A four-run third inning marred Nevers’ varsity baseball debut when he pitched seven innings at home on March 8, 1924. Stanford lost to the San Francisco Olympic Club, 5-2. Later, he started the final five games of the season which included a shutout against St. Mary’s College of California and a three-hit victory over Santa Clara before the concluding series against California.

Nevers hit a home run and pitched a complete game in the 5-4 loss at Berkeley on April 12. He hit another home run and went the distance as Stanford stormed back to win, 7-2, on April 19, also at Berkeley. Finally, on April 26, he took a 7-1 lead into the eighth before being lifted for a reliever. Stanford hung on for a 7-6 home victory.

In his first game of the 1925 season, played at home on March 14, Nevers tossed a shutout and hit two triples against Oakland’s Ambrose Tailors.

On a trip to Los Angeles, Stanford lost at Occidental, 6-5, on March 24. Bud Teachout went the distance for the home team. Nevers took the loss, but he followed by hurling a complete game to beat USC, 2-1, on March 27.

Rain delayed the season-ending series against California. The time off did not benefit Nevers; when he started at their matchup in Berkeley on April 11, California’s Jimmy Dixon hit a first-inning three-run homer and a third-inning grand slam off a reliever after Nevers issued three walks. Tagged with the loss, he allowed seven runs in the 27-5 rout.

Nevers redeemed himself.

When the teams met again, on April 18, he blasted the longest home run ever hit at Stanford. He also scored the tying run on Chuck Johnston’s walk-off two-run single that gave him a complete-game win, 4-3.

They met once more, at Stanford on April 25. For what turned out to be his final college game, “No athlete of fiction or reality ever had a game made more to his order than this [one],” reported the San Francisco Examiner.8 “… He hit a grand slam on a full count with two outs in the third inning. He also hit a triple and tossed another complete game in the 8-4 win.

Nevers left Stanford after the 1925 fall semester to pursue professional sports. Football came first, but he sent this telegram on the same day that he played his first pro gridiron game: “Jacksonville, Fla., Jan. 2 — Harry B. Smith, Sporting Editor The Chronicle, San Francisco. Signed contract with the St. Louis Browns today. ERNIE NEVERS.”9

He was not alone among football players to be given a chance at pro baseball. Others included Jackson Keefer, Doug Wycoff, Pooley Hubert, Joe Guyon, Red Strader, and Red Barron. In 1919 George Halas had played for the New York Yankees.

Nevers had a whirlwind schedule in the early weeks of 1926 before reporting to spring training at Tarpon Springs, Florida, on February 27.

First, he played two football games in Jacksonville for an upstart team dubbed the All-Stars. The team disbanded prematurely on January 12 due to low attendance and the promoters’ financial losses. He then headed north to Madison, Wisconsin, to visit Paul “Puddy” Nelson, his Superior teammate who became a star football player for Wisconsin. While there, he practiced with and instructed the Badgers pitching corps while Ray Schalk worked with the catchers.10

First, he played two football games in Jacksonville for an upstart team dubbed the All-Stars. The team disbanded prematurely on January 12 due to low attendance and the promoters’ financial losses. He then headed north to Madison, Wisconsin, to visit Paul “Puddy” Nelson, his Superior teammate who became a star football player for Wisconsin. While there, he practiced with and instructed the Badgers pitching corps while Ray Schalk worked with the catchers.10

Nevers dabbled in pro basketball by playing three games for the Milwaukee Swendson Fords. Milwaukee beat the Chicago Capper & Capper Big Five at home on January 27, lost at Chicago on February 4, and defeated the New York Nationals at home on February 8. In between, he slipped in a stop in Superior for the dedication of the normal school’s gymnasium on January 30.

Nevers married Mary Elizabeth “Mae” Heagerty on February 16, 1926, in San Francisco. Baseball altered their summer wedding plans as they opted for an impromptu informal ceremony at a friend’s house. (Mae’s brother, Leo Heagerty, became a Stanford catcher whom the Boston Red Sox signed in 1937. He played in the minors for two years.)

The Browns spent their second of three spring training camps at Tarpon Springs in 1926. Universal Services’ Warren Brown wrote, “The chief object of interest among the pitchers, is a football player, Ernie Nevers. … He has some of the pitching mannerisms of Carl Mays, and of Grover Alexander.”11

Nevers made his major-league debut as a pinch-hitter on April 26 at home against Cleveland. He was struck out by Joe Shaute to end the game. Details of the inauspicious start made their way across the country when it was mentioned in a syndicated column by Billy Evans. Nevers hit two long fouls before missing on a high fastball.12

Nevers did not play again for two months. Controversy ensued.

He missed a three-week road trip due to a disagreement with club policy. He wanted Mae to make the trip but wives were not allowed to travel with the club.13 Newspapers compared the situation to that of Urban Shocker a few years earlier; the Browns dealt with Shocker by trading him to the Yankees in 1924. Also, the Browns wanted to send Nevers to Tulsa for seasoning, but he refused on the grounds of his “ironclad contract for the full season.”14 Nevers spent his time as a batting-practice pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals.

On May 9 it was reported that Nevers joined teammate William “Pinky” Hargrave and Red Grange in buying Auburn cars.15 News of his buying a car one day and playing semipro ball for Moberly, Missouri, the next seem to go hand in hand. Pitching against Hannibal, he allowed 10 runs as Moberly lost, 19-4.16

While it was player-manager George Sisler’s intent to bench Nevers for the season, St. Louis limped back home with a 9-29 overall record and sorely lacked pitching depth.17

Nevers threw a six-hitter in an exhibition game as the Browns beat the semipro Massillon Agathons 3-2, at Massillon, Ohio, on June 23, setting up his major-league pitching debut on June 28, 1926.

Sisler sent him in for the bottom of the eighth at Chicago with the Browns trailing, 5-0. The first three batters hit singles with one run across before Schalk came to bat. With two runners on base and no outs, Schalk put down a sacrifice bunt. Was it out of mercy for his fellow Badgers coach? Another run scored when pitcher James Edwards also bunted for an out. Johnny Mostil then flied out to end the inning. St. Louis lost, 7-0.

Nevers did not play again for three weeks. Meanwhile, his signing to play in the NFL hit the news on July 11.

In his next appearance, at New York on July 19, he entered to pitch the bottom of the third inning with St. Louis trailing the Yankees 8-2. Babe Ruth walked to load the bases with two outs, which brought Lou Gehrig to the plate. If the Iron Horse had come through, perhaps Nevers’ baseball career would have been much shorter. But Gehrig flied out, and Nevers finished the game, allowing six hits and three runs in six innings, walking three batters and striking out two. He also got his first hit, a single off Shocker, in the 11-2 loss.

Nevers made his first start in the second game of a doubleheader on a rainy July 24 at Boston. The field conditions affected first baseman Sisler’s ability to convert what would have been the final out to secure a complete-game win. Instead, the Red Sox plated two runs to tie the score, 5-5, and that is how it ended because the Browns had to catch their train to Cleveland.

Nevers made two relief appearances to round out the month before entering the starting rotation for August. He had six starts. The first three were high-quality complete games, the final three mediocre.

In the first of the six starts, he came close to throwing a shutout at home against the Philadelphia Athletics on August 4. He took a 3-0 lead into the ninth but surrendered a run when Sammy Hale doubled with two outs and scored on a single by Al Simmons. When Walt French grounded back to him, Nevers threw to Sisler to secure his first win.

In a home game on August 8, Boston broke a 2-2 tie with two runs in the top of the ninth to hand him his first loss. Only one of the four runs was earned. Nevers notched his second win at home on August 12, when St. Louis defeated Detroit, 7-2, with Nevers allowing eight hits while walking two and striking out five.

In 1926 major-league teams rescinded their unwritten policy of not allowing wives on road trips. The St. Louis Cardinals allowed Grover Cleveland Alexander’s wife to accompany her husband “in view of the fact that he was keeping late hours in Chicago and lost his job for that reason,” according to the Morning Call of Allentown, Pennsylvania. The newspaper also mentioned the conflicts that Shocker and Nevers had with the Browns.18 The Cardinals’ change of heart paid off as Alexander led them to their first World Series championship, though the legend lives on regarding his degree of sobriety in his legendary postseason performance.

Mae Nevers accompanied the Browns on their next road trip. The results were not favorable, Ernie started and lost at Boston on August 17, at Washington on August 24, and at Philadelphia on August 28. He failed to get past the seventh inning in any of the three games.

A few days later, Ernie and Mae left St. Louis under cover of darkness — in the early morning, before sunrise — without telling the Browns that they were leaving, to join the Duluth Eskimos NFL team’s training camp in Two Harbors, Minnesota. He reported for duty on September 6, the second day of the first NFL training camp. St. Louis lost 17 of 27 games without him to finish in seventh place at 62-92, 29 games behind the Yankees.

Nevers scored 30 points as his Duluth Eskimos beat the St. Louis Blues, 48-0, at the Browns’ Sportsman’s Park on November 6, 1926. Meeting with Browns owner Phil Ball, he resolved the issue of leaving the team early by asserting that business manager Bill Friel reneged on his verbal agreement that he could leave for football if the Browns were out of contention. Expecting ire, Nevers instead left the meeting with a pay raise. He did not leave baseball prematurely for football again.19

Duluth played its final game on January 9, 1927, in San Francisco. At month’s end, Nevers was seen playing baseball at Yosemite National Park, ostensibly in preparation for the coming season but while wearing snowshoes. He played one more football game on February 6. It was at least his 30th in five months.

Nevers missed the preliminary week of spring training in Tarpon Springs, but arrived on Saturday, February 26, “in time to do considerable damage to the supper meal,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.20 (Nevers lost 25 pounds on the grueling football tour.21) Illness then cut his preseason short and he returned to St. Louis ahead of the team.

The Browns’ offseason maneuvers in hopes of turning their fortunes around did not take immediate hold. St. Louis hired manager Dan Howley and coach Bill Killefer. While they were unsuccessful in their bid to sign Ty Cobb, Sisler stayed on as first baseman and improved his batting average from .290 in 1926 to .327 in ’27. But it was more of the same for the Browns, or the clowns, as Killefer called that season’s team. St. Louis finished seventh again, this time 50½ games behind the Yankees, to whom they lost all but one of their 22 contests.

Howley called on Nevers 22 times that season, more than any other reliver. He also made five starts. When he started against New York on May 11, Ruth greeted him with a two-run homer in the first inning. New York won, 4-2, but he blanked Murderers’ Row for the final six innings and allowed fewer hits (7) than winning pitcher Shocker (8), who also went the distance.

Nevers tossed two shutout innings in relief while St. Louis rallied for an 8-6 lead at home against Detroit on July 6. In the eighth inning, Browns rookie center fielder Fred Schulte slammed into the concrete wall and was knocked unconscious and broke his wrist in his effort to make the catch on a leadoff double. When play resumed, the Tigers commenced to score three runs off Nevers and went on to win, 9-8.

Nevers surrendered a three-run homer to Gehrig at St. Louis on July 18, putting the Iron Horse ahead of the Bambino for the season’s home-run lead, 31-30. This was Nevers’ last game for 40 days as he underwent an appendectomy on July 20. He traveled to Moose Lake, Minnesota, to convalesce. St. Louis went 12-24 during his time away, including losing 16 of 19 on a road tour.

In Nevers’ first game back, Ruth hit a triple as the first batter he faced upon entering to pitch the fifth inning at home on August 27. Ruth followed by swatting a two-run homer in the eighth, his 41st of the season, securing Nevers’ place in baseball trivia for having allowed two of the Babe’s 60 bombs in 1927. Nevers then walked Gehrig and gave up a homer to Bob Meusel before getting the hook. St. Louis, trailing 5-1 when Nevers entered, lost, 14-4.

Nevers made just three appearances in September, all in relief. He was not scored on in 8⅔ innings. He made the final start of his major-league career at Chicago on October 1. It was the second game of a doubleheader on the second-to-last day of the season. Chicago won, 5-3, in five innings with Nevers taking the loss. The game was called due to darkness.

For the season, Nevers went 3-8 with a 4.94 ERA. Could he have had a better season if not for the toll that football took on his body? If not for appendicitis? If he had played for a winning team?

Nevers had seven days to prepare for his second NFL season, a nine-game road tour from October 9 to December 11. He played the last of a series of exhibition football games in California on February 5, 1928. It was announced on February 11 that he would retire from pro football to be an assistant coach at Stanford.22

He again reported to the first full practice instead of the pitchers-and-catchers week of spring training. The Browns held camp at West Palm Beach, Florida, and Nevers arrived on February 27 declaring that he desired more pitching work than in the previous season.

Newspapers reported that Nevers worked with Bill Killefer on altering his throwing style from side-arm to overhand and eliminating a full windup from his repertoire in attempts to throw harder and pay closer attention to baserunners, respectively. A more likely rationale: “In 1928, when he reported to the Browns, he was racked by football injuries. They included two broken ribs. One of them pressed against a nerve in his back so severely that every movement produced agony,” wrote Jim Scott.23

More agony occurred when Nevers and teammate Jack Ogden spent too long at the beach on March 7. Both men were sunburned enough that they could not practice. Howley outlawed sunbathing.

“Nevers is still in the ‘guess class,’” James M. Gould wrote in the St. Louis Star and Times during the Browns’ preseason schedule. “One day he looks like a million dollars and the next like 30 pesetas.”24

In the Browns’ third game of the season, Howley inserted Nevers to pitch the bottom of the ninth inning at Detroit on April 13. He tossed three shutout innings, allowing two hits while walking two batters, gaining credit for the win in the 11-inning contest. It was the first, and longest, of his six appearances, all in relief, that spring.

A scorekeeping oversight that charged Nevers with the loss in a game against Chicago on April 28 was corrected in July. The change might not have been as newsworthy except that the actual loser, General Crowder, otherwise would have had an 11-0 record before taking a loss on July 20. Crowder finished 21-5 in 1928, a season in which the Browns finally turned the corner by finishing in third place with an 82-72 record. But Nevers, who had survived an offseason of roster overhauling, was not around for much of it. He made six appearances in the team’s first 22 games, and then he was gone.

Making his final major-league appearance at Washington on May 4, he allowed one unearned run in one inning in the Browns’ 13-6 loss.

On May 23 St. Louis sold Nevers to the Mission Bells of the Pacific Coast League, a team that shared San Francisco’s Recreation Park with its more famous league rival, the San Francisco Seals.

Mission, named for the Mission District neighborhood, was in its third season. It was also the last in which it would be called the Bells. Manager Wade “Red” Killefer, Bill’s brother, changed the name to the eponymous Reds in 1929.

Nevers started the second game of a doubleheader against the Seals on May 27. He went only two innings in his initial outing, both three-up-and-three-down. “The only reason that the blond giant was started is that Killefer did not want to disappoint the hundreds who came out to see him. … Nevers, it develops, has been a sick man for the past three weeks. … Ernie is suffering from a severe cold and a bad attack of lumbago, his actions indicating that it was only with effort that he could get the ball over,” wrote Abe Kemp in the San Francisco Examiner.25

For his next game, 13,000 people assembled for Ernie Nevers Day at Recreation Park as the Bells hosted the Oakland Oaks on June 2. Nevers started and worked into the 10th inning before giving way to reliever Elwood Good “Speed” Martin. Martin induced a double play on the only batter he faced before Mission scored in the bottom of the frame to win, 8-7.

Nevers made 29 pitching appearances for Mission in 1928, with 25 starts. He had 16 complete games, two shutouts, and a string of eight straight wins. He tossed a one-hitter and two four-hitters in consecutive starts during the hot streak. It was not all dominance. His record for the season was 14-1226 and opposing lineups reached double digits in hits in 10 of his starts.

He hit .374 (34 for 91) in 35 games, with the highlight of his batting career occurring at home on July 19. He had four hits, including two home runs, and five RBIs while tossing a four-hitter to beat the Los Angeles Angels, 13-4.

Besides coaching football at Stanford after the season, Nevers played for the state champion Santa Rosa American Legion football team called the Bone Crushers.

Mission’s training camp commenced at Stockton, California, on February 19, 1929, with Nevers present on day one. He was heard to ask, “Is this a ball club or a track team?” regarding Red Killefer’s penchant for heavy conditioning workouts.27

Mission won the first half of the season with a record of 60-33. Nevers played in 21 of the 93 games. For the overall season, he had only 36 appearances. He had a 5-0 record to start the season but finished at 7-8. He had just eight starts in the 196-game season, with five complete games.

It was announced on July 29 that Nevers had signed with the Chicago Cardinals and would be returning to the NFL in the fall.

Mission was tied for first place with Hollywood with four games left to play. On October 4, Nevers allowed three earned runs in 7⅔ innings against Seattle at home. Mission already trailed, 9-1, when he took over in the second inning and the team lost, 13-6. Hollywood downed Portland to take the lead.

The next day, Herman Pillette threw a no-hitter in Mission’s 4-0 win over Seattle, but Hollywood won as well.

Both teams had doubleheaders scheduled for the final day, October 6. Portland took both games at Hollywood to finish in third place at 57-46. The Reds hosted last-place Seattle (28-75) but lost the first game in 12 innings.

Killefer started Nevers in the nightcap. Abe Kemp wrote in the Examiner, “Ernie Nevers’ farewell was indeed brief. He was batted out in the first inning, [Bill] Allington greeting him right at the start with a home run over the right field fence. [Charlie] Wade doubled and when [Lou] Almada singled to score him, he was taken out and replaced with Bill] Hubbell. Nevers left immediately to join the Chicago Cardinals.”28

The score remained 2-0 until Seattle scored six in the eighth, which secured the 9-1 upset. Hollywood finished 61-42. Mission, 60-43. Hollywood took the PCL championship by beating the Nevers-less Reds, four games to two, in the postseason series.

Nevers missed the Cardinals’ first two games because of baseball but was back in NFL action on October 13 in Minneapolis. Having played the final game on December 8 in East Orange, New Jersey, Nevers flew to California, arriving at his father’s bedside in a Santa Rosa hospital on December 12. The elder Nevers had suffered a heart attack and was not expected to survive. But he was back home for Christmas and had his family together to boot.

Ernie laced up for the Bone Crushers to help them win another state championship game on January 5, 1930, in San Francisco. He then switched to basketball and played for Santa Rosa’s American Legion team for the remainder of the winter.

Nevers missed the first 10 days of Mission’s spring training in 1930 because his father had another heart attack. (The reports of George E. Nevers’ death in various newspapers on March 5, 1930, were greatly exaggerated; he lived until 1933.) Ernie reported for duty at Stockton on March 12, but the Reds released him from camp on April 6. Switching to semipro baseball, he played for Marlow Music House, a Santa Rosa team in the Redwood Empire League.

Nevers took on being the head coach of the Chicago Cardinals for the final two years of his NFL career, 1930-31. Still playing football in California beyond the end of the 1931 NFL season, he broke his wrist in the last play of a charity game on January 25, 1932, in which he scored four touchdowns. After the game, he said he was done playing football and that he was “through with baseball, too.”29

Nevers was an assistant football coach at Stanford from 1932 to 1935. Then he was head coach at Lafayette for one season, 1936. From there he spent two years (1937-38) as an assistant at Iowa, working with head coach Irl Tubbs, his coach at Superior Central. He was then back in the NFL, as head coach of the Chicago Cardinals in 1939.

Nevers had offers from movie studios in 1926 but did not pursue acting at that time. With his pro sports career behind him, he finally made his way to Hollywood in the summer of 1932 and appeared in two releases later that year.

His first film, with a plethora of also-uncredited football players, was The All-American, a football film starring Richard Arlen, Andy Devine, and Gloria Stuart.

His major acting credit is The Lost Special, a 12-part serial Western based on a short story by Arthur Conan Doyle. He co-starred with Frank Albertson and Cecilia Parker.

Nevers had another uncredited part, in Saturday’s Millions in 1933, also a football movie starring Andy Devine. Later, he and fellow Stanford football star Keith Topping signed on for uncredited roles in 1936’s Robin Hood of El Dorado. Nevers played himself in The Spirit of Stanford, a 1942 movie starring Frankie Albert, yet another Cardinal gridiron great.

Ernie worked in public relations for Seagram’s Distillery in San Francisco before being sworn in as a captain in the Marines in 1942. After training in Quantico, Virginia, he was serving in Southern California in preparation for shipment to the South Pacific when he was summoned to return to San Francisco. Mae had fallen ill with pneumonia. She was already unconscious when he arrived on July 11, 1943, and she died two days later at age 33. She is buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Oakland, her hometown. He left for combat later that year.

Sports columnist Prescott Sullivan reported on Nevers’ return on September 10, 1944, after spotting him eating dinner at a San Francisco café. Sullivan wrote that Nevers had been at Bougainville and Green Island, among other places, but that “an old football injury had hastened his return home. … ‘My back hurt so that I couldn’t sleep o’ nights,’ he said, ‘so they shipped me out of there. I can’t say that I was sorry to leave. No one ever is.’”30 He received a promotion to major while serving stateside.

Upon his discharge in the summer of 1945, Nevers moved to Chicago to become an assistant coach for the Chicago Rockets of the All-America Football Conference. Nevers married Margery Luxem in Chicago on January 31, 1947. He retired from coaching and the couple moved to California. They had a daughter, Ernestine (Tina), born in 1948.

Nevers worked as public relations director for Grace Brothers’ Brewing Company in Santa Rosa and as such began hosting a sports analysis radio show in 1947. He held the same position for the California Wine Association in the 1950s.

Nevers died at Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, California, on May 3, 1976, at the age of 73, of kidney disease. “I will always feel that what is most important about Ernie is not what he did as an athlete but what kind of man he was, the way he enjoyed life, and the gracious, kind human being that he was,” Margery said in 1977.31

Margery died in 2009 at age 98. The couple lie in eternal rest at Mount Tamalpais Cemetery in San Rafael, California.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Ashley McDonald and Teddie Meronek for research assistance. Also, a special thank-you to Tina Nevers and Jennifer Nevers Luckwitz for their correspondence and insight.

This biography was reviewed by Steve Rice and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the following:

Elliot, Lawrence. “Eight All Americans,” Coronet, December 1954.

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Findagrave.com

Genealogybank.com

Newspapers.com

Pro-football-reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Ernie Nevers.

Notes

1 The charter Pro Football Hall of Fame class also included Cal Hubbard, who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976 as an umpire.

2 Richard Gibson. “‘Ernie Nevers?’ Few Remember Him Now,” Minneapolis Star, June 29, 1972: 1-2.

3 “Moose Lake,” Duluth (Minnesota) News Tribune, May 26, 1908: 2.

4 George H. Hayward, The Nevers Family, Fredericton, New Brunswick, 2006: 143.

5 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census.

6 “Dies in Flames at Moose Lake,” Duluth News Tribune, May 11, 1912: 11.

7 “Stanford Frosh Beat Berkeley Hi,” Oakland Tribune, March 11, 1923: 56.

8 William Leiser, “Nevers’ Homer Beats Bruins,” San Francisco Examiner, April 26, 1925: 97.

9 Harry B. Smith, “Ernie Nevers Signs to Play as Pitcher in Saint Louis,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 3, 1926: 45.

10 “Schalk and Nevers Show Badgers Fine Points of Baseball,” Morning Star (Rockford, Illinois), January 30, 1926: 12.

11 Warren Brown, “Nevers Compared with Mays, Alexander by Sport Critic,” San Francisco Examiner, March 11, 1926: 35.

12 Billy Evans, “Billy Evans Says: Debut of Nevers,” Des Moines Tribune, May 3, 1926: 21.

13 “Ernie Nevers Left in St. Louis When Browns Departed,” St. Louis Star and Times, May 6, 1926: 23.

14 “Ernie Nevers Is Nicked for Three Hits in Inning,” Oakland Tribune, June 29, 1926: 23.

15 “Players Driving Auburn Cars,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 9, 1926: 66.

16 “Hannibal Is Winner Over Moberly, 19-4,” Macon (Missouri) Chronicle-Herald, May 10, 1926: 1.

17 Gordon Mackay, “Nevers Makes Good,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1926: 47.

18 “Players’ Wives May Go on Trips,” Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), August 11, 1926: 18.

19 Bob Broeg, “Meet Ernie Nevers, the Baseball Player,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 4, 1958: 72.

20 Marion F. Parker, “Stage Set for Arrival of Browns’ Main Squad at Tarpon Tomorrow,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 27, 1927: 12.

21 Chuck Frederick, Leatherheads of the North (Duluth, Minnesota: X-communication, 2007), 107.

22 “Returns to Alma Mater,” Modesto (California) News-Herald, February 11, 1928: 28.

23 Jim Scott, Ernie Nevers, Football Hero, (Minneapolis: T.S. Denison & Co., Inc., 1969), 81.

24 James M. Gould, “Three New Moundmen May Prove Big Assets to Revamped Browns,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 4, 1928: 22.

25 Abe Kemp, “Bells Split with Seals; Take Series,” San Francisco Examiner, May 28, 1928: 19.

26 The author’s research shows 14-12 while Baseball-Reference.com reports 14-11.

27 Cliff Frisbie, “Killefer Puts Missions Through Still Paces at Oak Park; Nevers on Job,” Stockton (California) Independent, February 20, 1929: 7.

28 Abe Kemp, “Hollywood Takes Second Half Honors,” San Francisco Examiner, October 7, 1929: 24.

29 “Nevers Nurses Broken Wrist as Price of Gridiron Victory,” Santa Rosa (California) Republican, January 25, 1932: 5.

30 Prescott Sullivan, “The Low Down,” San Francisco Examiner, September 10, 1944: 17.

31 Roger Williams, “Never Another Like Nevers,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 25, 1977: 37.

Full Name

Ernest Alonzo Nevers

Born

June 11, 1902 at Willow River, MN (USA)

Died

May 3, 1976 at Greenbrae, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.