Farmer Weaver

In the early years, baseball had its share of Buck Weavers, but the most famous among them was not the “original.” That distinction, according to sportswriter Fred Lieb, goes not to the White Sox infielder, but to William Clinton Bond Weaver, known more commonly today by his other nickname, “Farmer.”1 This Buck Weaver started his major league career before the Chicago player was even born, but he, too, once played for a team that came to be known as the Black Sox. He, too, was acquainted with scandal.

In the early years, baseball had its share of Buck Weavers, but the most famous among them was not the “original.” That distinction, according to sportswriter Fred Lieb, goes not to the White Sox infielder, but to William Clinton Bond Weaver, known more commonly today by his other nickname, “Farmer.”1 This Buck Weaver started his major league career before the Chicago player was even born, but he, too, once played for a team that came to be known as the Black Sox. He, too, was acquainted with scandal.

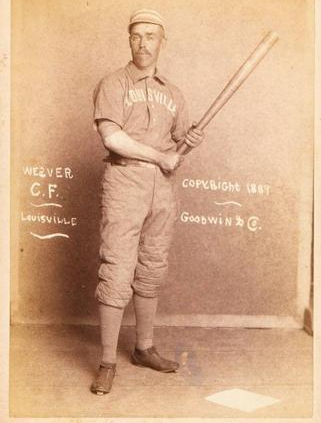

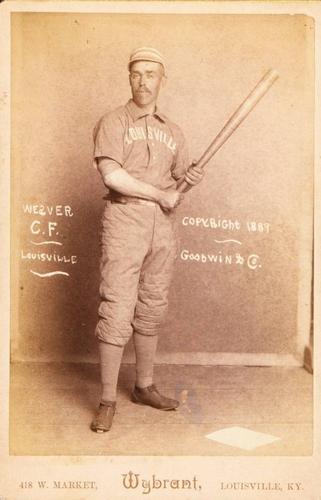

Weaver was a nineteenth-century player whose major league years occurred between 1888 and 1894. During that time, he registered a career batting average of .278 and produced 344 RBIs in 753 games, most of which he started as an outfielder for the Louisville Colonels.

At the plate, Weaver was a switch-hitter who exercised fine bat control and who had a flair for timely hitting.2 In the outfield, he defended his territory with skill and finesse, and made the occasional eye-popping play. He brought added value with his versatility as a backup catcher, his heady base running, and his general baseball smarts.

In the view of the Louisville Courier-Journal, Weaver was “a good ball player—not a star, but a good, all-around man, better than the majority in the big League …”3 He laid claim to one truly exceptional major league achievement, one that was probably underappreciated at the time: he went six-for-six in a regulation game while hitting for the cycle. The six-hit/cycle combination is a feat so rare that not a single major leaguer accomplished it during the entire twentieth century.4

Over nearly three decades, Weaver played the game at all levels and tried every role that the sport offered up to him—player, field captain, manager, promoter, scout and umpire—albeit briefly in some cases. Personal failings unrelated to baseball produced the most riveting chapter in his life story, however. In the fall of 1911, Weaver’s world imploded in stunning fashion. For years, he had carried a dark secret. When finally exposed, its serious nature brought humiliation, shame, and worse. In quick succession, he became a fugitive, a convicted felon, a prison inmate.

After serving his time, Weaver settled into a life of relative anonymity, and that, too, is how his life began. He was born near Parkersburg in Wood County, West Virginia, in 1865, or perhaps late 1864. Baseball sources give the date of his birth as March 23, 1865, although there is some uncertainty on this score since Wood County records do not include William Weaver among the births registered in 1865.5 Census records suggest that he was the son of German immigrants, George and Margaret Weaver, who settled in Pennsylvania before moving to West Virginia to farm. Weaver’s mother died when he was only 11, which also was the age at which he “left home.” His formal education ended after just four years of instruction.6

Weaver married at the age of 18, taking as his wife the very young Dora Dove Dye.7 She was 14 years old, 15 at the most, when they wed in Parkersburg in the fall of 1883. Soon thereafter, the couple followed the lead of Dora’s family in migrating west, to Kansas. The Dyes and the Weavers first settled in Johnson County, on the state’s eastern border, and later moved nearly 400 miles further west and south, to Kearny County, Kansas.

The Weavers’ move to Kearny County occurred in the fall of 1889 when they purchased a “fine farm” on a 160-acre tract east of the town of Lakin. The farm became Weaver’s off-season home throughout his career, and it was the first of at least four real estate investments that he and Dora would make to establish a farm and livestock operation. The initial purchase spawned the “Farmer” nickname, which began to appear in sports pages during the 1890 season, and which remains in common use today in baseball references. Unlike his nickname “Buck,” however, “Farmer” was likely a journalistic invention, rather than a form of address used in everyday conversation.8

While still in Johnson County, Weaver started his baseball career circa 1885 by joining Olathe’s barnstorming town team as a catcher. He soon graduated to the professional ranks, playing in 1886 with the Topeka Capitals of the Western League. In 1887, he signed with the Wellington Browns of the independent Kansas State League, and then with the Wichita Braves of the Western League. On these early teams, Weaver often alternated between catching and roaming the outfield.

The season’s work in 1887 produced a new contact, John J. McCloskey, who would figure large in Weaver’s future. That summer, McCloskey was only months away from earning his credential as the “Father of the Texas League.” His path and Weaver’s probably crossed for the first time in the Kansas State League, where McCloskey played briefly for the Arkansas City team. After the state league blew up, McCloskey went to Joplin, Missouri, and assembled a “star collection” of players from the Western and Kansas leagues. Weaver joined them after the Wichita Braves disbanded in early September.

McCloskey and his team, the Joplins, barnstormed through Texas that fall in a tour highlighted by a win against the New York Giants.9 The upstarts’ victory over the Giants, together with McCloskey’s powers of persuasion, spurred interest in organizing a new league in Texas, and also in securing McCloskey’s team to represent Austin.

Weaver opened the 1888 season as an outfielder/catcher for the Austin Senators in the fledgling Texas League, and he moved with the club when the franchise transferred to San Antonio mid-season. He was adept with the bat, and led the league in hits, with 90, and runs, with 66. One news account characterized Weaver as “the most valuable man in the team, possibly the most valuable in the Texas league.”10 The manager of the rival Dallas Hams, Doug Crothers, told a reporter that Weaver was “one of the best players I ever saw.”11

Texas brought another compliment that would become a lasting part of his persona, for it was there that he acquired the nickname “Buck.” McCloskey and his other teammates took to calling him that in flattering comparison to the hard-hitting, future Hall of Fame catcher, Buck Ewing. The nickname would stick with Weaver throughout his years in the game.

By early September 1888, at least three major league teams—Louisville, Cleveland, and Kansas City—had shown an interest in acquiring Weaver. Louisville, of the American Association, was the successful suitor. The Colonels signed him as an outfielder and expected him to catch only “in a pinch.” Weaver debuted with the Colonels during a series in Kansas City on September 16, 1888. At season’s end, Louisville’s columnist for Sporting Life judged him “one of the finest hitters in the Association, and a splendid fielder and base-runner.”12

Weaver had signed with a team soon to leave its mark on history.13 With a 27-111 record, the 1889 Colonels became the first major league team to record 100 losses. Their defeat-riddled season reached its nadir with 26 consecutive losses, a major league record. The sustained losing streak created pressures and tensions that resulted in a brief players’ strike, also a major league first. The strike occurred in mid-June when six Colonel players—Red Ehret, Paul Cook, Guy Hecker, Dan Shannon, Harry Raymond, and Pete Browning—failed to report for a game in Baltimore. Weaver chose not to join them.

In 1890, the Colonels erased the prior year’s embarrassment by engineering a total reversal of fortune. The team won the American Association pennant, finishing with a comfortable 10-game lead over its nearest competitor. In doing so, the Colonels became the first major league team to earn the “worst-to-first” title. After the 1890 season, however, even mediocrity was beyond the reach of the Colonels during Weaver’s remaining years with the team.

During his six years with Louisville, Weaver worked primarily as an outfielder. Upon joining the Colonels, he started a three-season run as the team’s regular center fielder, after which he played both of the other outfield positions. On several occasions, especially in the latter years, the team toyed with the idea of converting him into a full-time catcher. While he performed well in his role as a backup catcher, he was not effective at the position on a full-time basis and attempts to make him one were all short-lived.

Offensively, Weaver’s best seasons occurred in 1889-90. He had a batting average of .291 in 1889 and, along with fellow outfielder Chicken Wolf, was the team’s co-leader in hitting. In 1890, he scored a career-high 101 runs, and his season average of .289 nearly matched that of his rookie season. By any reckoning, Weaver had a career day in Louisville on August 12, 1890 when the Colonels defeated the Syracuse Stars, 18-4. He completely owned Ezra Lincoln and Ed Mars, the Syracuse pitchers, by hitting them for the cycle in a 6-for-6 outing.14 His base total for the day was 14, which he reached by hammering out two singles, one double, two triples, and one home run. He scored three runs and had one stolen base.

Also in 1890, Weaver had his only opportunity at postseason play in the majors. In one of the precursors to the modern World Series, the National League and American Association champions met for what was supposed to be a nine-game series. Shortened by weather to seven games, the series between Louisville and Brooklyn ended in 3-3 draw, with one contest ending in a tie because of darkness. Weaver played center field in all seven games, and compiled a .259 average in 27 at-bats. He drove in four runs, scored four, and stole five bases.

Weaver’s most accomplished season as a fielder came in 1891. In his book Baseball Pioneers, Charles Faber rated Weaver as the American Association’s leading outfielder that year. Although some variance exists among sources regarding the 1891 statistics, the 1990 Elias Baseball Analyst reports that Weaver led the league in fielding percentage, putouts, and assists in 1891, a feat not repeated by an outfielder until Gerald Young of Houston did it in 1989.15

Two unusual events occurred in 1893, both of which would be unheard of today. On July 4, in a game against Washington, Weaver celebrated the holiday with his own fireworks. He took his post in right field armed not only with his glove, but also with a pistol. When a high fly headed his direction, he fired at the ball as it arced downward, emptying the gun’s cylinder. He missed his mark, dropped the gun, then fielded the ball with his glove. He “created a sensation” among the Louisville fans and must have enjoyed doing it. Two years later, on the Fourth of July, he repeated the antic in a minor league game in Kansas City.

Later in 1893, Weaver entered the record books as a major league umpire. In an August road series between Louisville and the Cleveland Spiders, umpire Tom Lynch became too ill to work the second game of a doubleheader. The two managers—Buck Ewing of Cleveland and Fred Pfeffer of Louisville—had a bit of a row in deciding on a suitable replacement. They finally agreed to use a player from each team. Jack O’Connor, a Spiders’ catcher/outfielder, worked the indicator behind home plate, and Weaver was stationed off first base. He performed well and gave no grounds for complaint about his decisions. The Spiders’ starting pitcher in the game was Cy Young, whose win on the day was one of 34 that season.

Weaver’s performance in 1894 was lackluster, and it would be his last year in the majors. The Colonels released him in August during a series in Washington. Within days, Pittsburgh signed him as a utility player. Connie Mack, the Pirates’ manager, initially used him to fill a hole at shortstop, a position at which he had only two games of prior major league experience. Mack backed off the experiment after a dozen tries, and Weaver finished out his major league career as a catcher. At the age of 29, Weaver played his last game in Pittsburgh on September 29, 1894.

The Pirates released Weaver in the spring of 1895, after which he quickly signed as an outfielder with the Milwaukee Brewers of the Class A Western League. It was a good fit that would last for five seasons. Buck was popular with the Milwaukee fans, especially in the early years, and he thrived in the lower level of competition. His overall batting average with the Brewers was .333, ranging from a high of .357 in 1896 to a low of .283 in 1898. For three of his five seasons as a Brewer, Weaver again played for the legendary Connie Mack, and served as his field captain in 1897. In the spring of 1899, Mack declared that “… in all departments of the game [Weaver] has no superior in this League, his fielding being irreproachable and batting always timely …”16 A year later, Mack released him.

After Milwaukee, Weaver switched teams often, sometimes at a dizzying pace. In 1900 alone, he went from Cleveland to Syracuse to Denver. His game deteriorated significantly in 1900, but the Denver Grizzlies nonetheless hired him as their player/manager for 1901. For the first time, Weaver encountered a fan base that took a dislike to him. His sub-par play in 1900 had precluded him from developing much of a rapport with the Denver baseball community. When internal dissension and ineffective teamwork surfaced during the 1901 preseason, Weaver had no reservoir of good will to draw upon. The Denver Times lambasted the club management for entrusting the team’s fortunes to a man “… whose record [in 1900] shows him to be inferior to every man on the team and in whom neither players nor spectators have confidence.”17 The opposition to Weaver’s appointment as manager became so strong that fans threatened a boycott. The Grizzlies management caved and released him at the start of league play.

Weaver landed next in the Salt Lake area, where he played independent ball for the Lagoons, including a stint as the team’s manager in 1902, and also for the Salt Lake White Wings. He quickly became an influential figure in the Utah baseball community. In the short time he would spend in the Salt Lake area, Weaver “worked himself into the hearts of the fans,” became the “grand old man of Utah baseball,” and “probably was the most popular ball player who ever stepped on a Salt Lake diamond.”18

In the fall of 1902, Weaver moved on, joining the Butte Miners, a Class B team managed by his old friend John McCloskey. He stayed with “Honest John” for the next three seasons, following him to the San Francisco Pirates (1903), the Salt Lake Elders (1903), the Boise Fruit Pickers (1904), and the Vancouver Veterans (1905). Of these career stops, the one in Boise was the most noteworthy. The Fruit Pickers finished first in the four-team Class B Pacific National League in 1904, with an 82-49 record. Weaver captained the team and was instrumental in its success. At the age of 39, he hit for a .334 average, and led the league in hits, with 188. He not only excelled on the field in Boise, Weaver once again captivated the fans—earning their votes as the team’s most popular player and a gold watch in the bargain. The Idaho Statesman declared him “the most popular player that ever appeared in a Boise uniform.”19 The Salt Lake Herald reported that “… Buck holds the same hypnotic sway over the Boise fans that he does over Salt Lakers …”20

Life on the road appeared to be over for Weaver after the 1905 season. As baseball swung into high gear in 1906, Buck stayed home for the first time in two decades. He worked the farm near Lakin and showed an interest in local politics. In the 1890s, news items had alluded to his support for the Farmers’ Alliance and Populist movements, and had labeled him a Democrat. By 1906, however, he had aligned with the Republicans, Kansas’ dominant party, and was participating, at least to some extent, in local party affairs.

In 1908, Weaver, “at the solicitation of a large number of [his] friends,”21 decided to run for Kearny County Sheriff on the Republican ticket. He won the primary election by a single vote, outpolling his nearest competitor, 152-151. In a close general election contest, he garnered 49% of the votes but lost to the Democratic candidate, 390-375.

Weaver continued to play amateur and semi-pro baseball, but much closer to home. He was one of Kansas’ earliest baseball stars, and at this point in his life, still basked in the celebrity that had accrued from a successful career. In 1906-07, Weaver was the featured player of the Lakin town team. He also was in demand as a player-for-hire when other towns in southwestern Kansas sought to fortify their teams.

In August 1907, Weaver accepted an invitation to play for the team in Larned, Kansas, where he was an immediate hit with the local fans. He carried his affiliation with the Larned team into the 1908 season and solidified his popularity in the community. When town subscribers secured a Class D Kansas State League franchise in mid-season 1909, Buck joined the team in late July. That fall, Weaver agreed to manage Larned’s Wheat Kings in the upcoming season.

Expectations for the 1910 Wheat Kings were sky-high, but Weaver did not even last until the end of June. He resigned in the midst of an 11-game losing streak, amassing a managerial record of 15-25.22 After leaving Larned, he played briefly for two other Kansas State League teams, the Wellington Dukes and the Lyons Lions. He retired for good in August 1910, when he left the Lyons team to accept a scouting assignment to Texas on behalf of the Lincoln Antelopes. Weaver’s last game as a professional player occurred on August 16, 1910, when the Lions defeated the McPherson Merry Macks, 2-1. Weaver made a quiet exit, going 0-for-3 on the day.

In the 1911 season, Weaver turned to officiating, first in the Kansas State League and, when that league folded, in the Western League. In both circuits, sports page commentary was mixed on the subject of his umpiring skill. Some of the criticism was decidedly pointed, although it is hard to evaluate whether complaints sprang from honest assessment or from home team bias. The Great Bend Tribune railed against “… the wandering decisions of an old man whose eyesight was bad and whose judgment became … warped by anger.”23 The Hutchinson Daily Gazette called on Weaver to retire “… for the benefit of the game and for the benefit of his health.”24 In the Western League, the president of the Lincoln club filed a protest with league officials over the “worst umpiring” his team had seen all year.25 Weaver’s last umpiring assignment—a major semi-pro tournament in Albuquerque—also was marred by a controversy over his decision-making.

When Weaver returned to Kansas in late October 1911, he was only weeks away from experiencing a dramatic unraveling of his personal life, the makings of which had been in the works for several years. The first outward sign that all was not well in the Weaver household occurred in Boise, when Buck and Dora separated. He filed for divorce in October 1904, alleging infidelity on Dora’s part, and requested that the court grant him custody of the nine-year-old child in the couple’s care. The Weavers had no children of their own, but they had gained custody of an orphan, Cecille Price (whom they called Hazel Weaver), in Pueblo, Colorado, in September 1901.26 Weaver withdrew his divorce petition in March 1905, but he and Dora had not reconciled.

The couple remained separated but legally married for several years, with Dora in Idaho, and Buck and Cecille in Kansas. In September 1909, Buck filed another divorce action, this time in Kearny County, on grounds that Dora had deserted him in the “company of another man.”

Dora filed a cross-petition and cast a whole new light on Buck’s character. Until then, the public portrayal of Weaver’s personality had been mostly positive. In the context of his sports relationships, he was described as industrious, reliable, intelligent, affable, and quick to make friends. He often flashed a broad, toothy grin, which some likened to that of Teddy Roosevelt. In most of the communities in which he played, he quickly established an easy and loyal rapport with the fans. There were, however, hints of a more aggressive nature.27 On at least two occasions, Weaver was taken into custody for assault, once against a fan who heckled him during a game and once against a Milwaukee sportswriter. In Louisville, a reporter noted that no one on the Colonels team was quicker to fight than Weaver and gave a couple of examples of his flare-ups. These isolated references to Buck’s temper were nothing, however, compared to the allegations made by his wife in 1909.

According to Dora in her cross-petition, she had left Weaver because he “… frequently abused her, struck her and choked her and beat her in a most brutal manner and threatened to take her life and made it impossible to live with him without suffering repeated violence at his hands and without continued fear for her life …”28 She asked the court for a divorce on grounds of extreme cruelty and secondarily, on grounds of adultery.

In May 1910, the court ruled squarely in Dora’s favor by finding that her allegations of extreme cruelty were true, and that Buck’s allegations against her were not supported by the evidence. The puzzler in the judge’s decree was his decision regarding Cecille. He granted custody to Weaver “until further order of the court,” implying a future action that did not, in fact, materialize.

The court’s findings must have dealt a serious blow to Weaver’s reputation and standing in the Lakin community. As a practical matter, the decree also resulted in the liquidation of his real estate holdings in the ensuing months. So, what might have been a seasonal move to Larned in 1910 to manage the Wheat Kings looked to become a more permanent one for both him and Cecille.

Soon after they relocated, it became apparent that Cecille was pregnant, and she delivered a son in the fall of 1910. Buck laid the blame for her pregnancy on an unnamed youth from Lakin, but the rumor mill hummed with speculation about other possibilities. Social pressures did not abate, but seemed only to mount with time. Motivated at least in part by a desire to quiet the wagging tongues, Weaver decided to marry Cecille shortly after he returned to Larned at the end of his umpiring duties in the 1911 season.

Weaver was in the final stages of sorting out the legal difficulties—she had just turned 17, not yet old enough to marry without the consent of a legal guardian—when Cecille went to the authorities for help. The gist of the nightmare Cecille told was that Weaver had abused her since she was 11 years old, that he forced her to live with him, that he fathered her child, that she was terrified of him, and that she would never find it acceptable to marry him.

The Pawnee County Sheriff arrested Weaver for violation of the state’s rape statute on November 18, 1911. He was in custody briefly, then posted bond. A week later, he absconded and fled to Mexico. Weaver remained at large for a month, but was captured in El Paso when he re-entered the country. The case went before the Pawnee County District Court in early March 1912. After Weaver pleaded guilty to one of the two counts in the complaint, the judge imposed an indeterminate prison sentence of five to 21 years.

On March 11, 1912, Weaver entered Kansas State Penitentiary (KSP) as Inmate #4250.29 His timing was apt, arriving as he did in time for baseball season. According to the inmate newspaper, baseball was “… the most popular thing in here. … Only the parole list can stir up the men here more than the base ball games. …”30 That first summer of Buck’s incarceration, he managed one of the KSP teams to a 25-3 record, including a victory in the prison’s championship game.

In the winter of 1913-14, prison officials allowed Weaver a somewhat surprising privilege—the opportunity to coach an aspiring young pitcher, Lore Bader, of LeRoy, Kansas. A relative of Bader’s worked at the prison, and presumably brought the two together. Bader had a brief tryout with the New York Giants in 1912, and still had major league hopes. Weaver helped prepare him for the 1914 season with the Buffalo Bisons of the Class AA International League. The Penitentiary Bulletin reported that Weaver “took young Bader and worked him out till he was whipped into shape.”

Weaver became a member of the prison’s Athletic Committee in the spring of 1914, and served as its baseball advisor. The baseball program itself underwent a marked change that season. Previously, baseball activities at the prison were largely intramural in nature, that is, KSP inmates played other KSP inmates in organized leagues. In 1914 the intramural contests continued, but the prison also fielded a team of its best players to compete in games against outside teams.

The most noteworthy of these games—and perhaps a historically significant one—occurred on May 30, 1914, at the United States Penitentiary (USP) in Leavenworth, which is located only a few miles from the Kansas prison in Lansing. The wardens of the two prisons agreed to schedule a Memorial Day baseball game featuring inmate teams from their respective facilities. News articles at the time characterized the matchup as a “first” for the institutions involved. It may also have been the first time one prison hosted a visiting team of inmates from another prison.31 The federal penitentiary was represented by its best team, the Booker T’s, composed entirely of African-American players. KSP also fielded its finest, a racially integrated team which featured Weaver. The KSP team was victorious, winning “the convict title” by a score of 4-2.

The inter-prison experiment was sufficiently successful that the warden allowed KSP’s premier squad, now referred to as the Black Sox, to play a number of games outside the prison walls that summer against teams from the Lansing and Leavenworth communities. The Black Sox ended the season with a 14-4 record. Weaver’s statistics are incomplete, but through August 1, the 49-year-old had gone 12-for-30, for an average of .400, and had stolen three bases.

Nearly two years earlier, in November 1912, Kansas voters had unwittingly done Weaver a favor when they elected George Hodges as their governor. Incredibly, Hodges and Sam Seaton, his executive secretary and parole clerk, had both been teammates with Weaver in Olathe in the mid-1880s. Several months after Hodges’ inauguration, a news article appeared about Weaver’s ties to Hodges and Seaton, and their inclination to help out their old friend. According to the article, Hodges was willing to grant parole if the prosecuting attorney and district court judge in Pawnee County would support the action.

Hodges signed Weaver’s parole certificate on December 28, 1914, clearing the way for his release a few days later. Had he not known Hodges, Weaver might still have secured a governor’s parole before serving his minimum sentence (minus “good time” earnings), but it seems rather unlikely. At the time, Weaver was still a year away from parole consideration via the other available route, recommendation of the Corrections Board.

Weaver left prison having completed approximately three years of his sentence. News reports stated that he went to Illinois, where he had relatives. He eventually moved to Akron, Ohio, and settled into a blue-collar job at Goodyear before retiring sometime in the 1930s.

In the last decades of his life, Weaver lived alone. He died of cardiovascular and renal disease in Akron on January 23, 1943, at the age of 77.32 His death in the pre-dawn hours was apparently unattended, and he left no close relatives to mourn his passing.

Sources

Primary sources for baseball statistics relating to Weaver’s career include Major League Baseball, Retrosheet, Baseball Almanac, Baseball-Reference, Sporting Life, Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball-Third Edition, and the SABR Encyclopedia website.

Daily and weekly newspapers were major sources of information about both his career and personal life. Notable among the numerous newspaper sources consulted were Sporting Life, The Sporting News, and local papers in those communities where Weaver lived and/or played ball, including Louisville, Milwaukee, Salt Lake City, Boise, Lakin, Larned, Lansing, and Leavenworth.

Other sources are identified below:

Akron-Summit County Public Library. Akron city directories for selected years. http://www.ascpl.lib.oh.us/internetresources/sc/CityDirectories/index.html.

Bailey, Bob. “The Louisville Colonels of 1889.” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, SABR, Number 14, 1994, 14-17.

Bailey, Bob. “The Louisville Colonels of 1890.” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, SABR, Number 13, 1993, 66-70.

Baseball Almanac at baseball-almanac.com.

Edelman, Rob. “King Bader.” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/king-bader/.

Faber, Charles F. Baseball Pioneers: Ratings of Nineteenth Century Players. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1997.

Jewell, Anne. Baseball in Louisville. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff, ed. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball-Third Edition. Durham, NC: Baseball America, 2007.

Kansas State Census for Kearny County: Lakin, March 1, 1895; and Lakin Township, March 1, 1905.

Kansas State Penitentiary. Inmate records on file at the Kansas State Historical Society.

Kearny County District Court. William Clayton [sic] Bond Weaver, Plaintiff, vs Dora Weaver, Defendant case file, 1909-1910. (Note: Court documents spell one of his middle names as “Clayton.” However, wherever his signature appears in these documents, he clearly signed this part of his name as “Clinton.” Also, the Wood County, WV record of his marriage identifies him as William Clinton Bond Weaver.)

Kearny County Historical Society. History of Kearny County, Kansas – Volume 1. Lakin, KS, 1964.

Kearny County Register of Deeds. Land transaction records.

Lieb, Frederick G. Connie Mack, Grand Old Man of Baseball. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945.

Major League Baseball. Historical Player Stats at mlb.com/mlb/stats.

National Baseball Hall of Fame, Giamatti Research Center. Player file for William B. Weaver.

Pajot, Dennis. The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwest Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1859-1901. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009.

Pawnee County District Court. State of Kansas vs. W.B. Weaver case file, 1911-1912.

Podoll, Brian A. The Minor League Milwaukee Brewers, 1859-1952. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2003.

Retrosheet at retrosheet.org.

Ruggles, William B. The History of the Texas League of Professional Baseball Clubs. Dallas: Texas Baseball League, 1932.

Siwoff, Seymour, and Steve Hirdt, Peter Hirdt, and Tom Hirdt. The 1990 Elias Baseball Analyst. New York: Collier Books, Macmillan Publishing Company, 1990.

Society for American Baseball Research. SABR Encyclopedia at sabrpedia.org.

Sports Reference LLC, Minor League Baseball History at baseball-reference.com/minors; and 1889 American Association Fielding Leaders at baseball-reference.com/leagues/AA/1889-fielding-leaders.shtml.

State of Ohio Department of Health. Certificate of Death—William B. Weaver, 1943.

Third Judicial District of the State of Idaho, In and for the County of Ada. Willam B. Weaver, Plaintiff, vs. Dora D. Weaver, Defendant case file materials, 1904-1905.

United States Bureau of the Census. United States Census: 1870 (Wood County, WV); 1910 (Kearny County, KS); 1930 (Akron, OH).

United States National Archives and Records Administration. Land Entry File for William B. Weaver under the Homestead Act, Final Certificate Number 5956 (Section 20, Township 23, Range 35).

Von Borries, Phillip. Legends of Louisville. West Bloomfield, MI: Altwerger and Mandel Publishing Co., 1992.

Wood County, West Virginia. Birth and marriage records at http://www.wvculture.org.

Notes

1 Frederick G. Lieb, Connie Mack, Grand Old Man of Baseball, (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1945), 54. According to Lieb, William B. Weaver was “the original Buck Weaver, and all subsequent Buck Weavers were nicknamed after him.” There was, however, at least one Buck Weaver who pre-dated him—Sam Weaver, a major league pitcher in the 1870s and 1880s. In addition to George Daniel Weaver of the White Sox, at least one other major leaguer, Art Coggshall Weaver, carried the nickname for a time. There were several minor league Buck Weavers.

2 Most baseball references count him as a left-handed hitter. However, several newspaper articles referred to his switch-hitting ability.

3 “Gossip of the Game,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 30, 1893, 6.

4 Ian Kinsler of the Texas Rangers had a six-hit cycle on April 15, 2009. Some of the news reports at the time stated that it was the first six-hit cycle since Weaver did it in 1890; others reported that it was the first six-hit cycle since Sam Thompson of the Phillies did it in 1894. According to the box score in “The Heavy Hitting Phillies,” (Washington Post, August 18, 1894, 6), Thompson did have a six-hit cycle in the August 17, 1894 game against Louisville. Weaver caught for Louisville in the game; it was his last appearance for the Colonels.

5 Wood County records do not list the birth of William Weaver in either 1864 or 1865. However, there is a record for the birth of William Weiber on December 28, 1864 to George Weiber, farmer, and his wife Margaret. The 1870 federal census for Wood County has an entry for George and Margaret Weaver, whose children included a son Willie, age 5—suggesting that the two sets of records may refer to the same family. The birth date of March 23, 1865 appears in standard baseball references. The only original source found that cites this as Weaver’s birth date is the death certificate. It appears, however, that the “informant,” or source of information, for the death certificate was a funeral home employee. Whenever an age is given in the bio, it is based on the March 1865 date, but with the caveat that the date is open to question.

6 Information about his mother’s death, the age at which he left home, and his education was documented during the intake process upon his admission to Kansas State Penitentiary.

7 Wood County records indicate that William Clinton Bond Weaver was 19 and Dora Dove Dye was 15 at the time of their marriage on November 19, 1883. However, other available information about their birth dates suggests that Weaver was 18 and Dye was 14.

8 Once Weaver left Louisville, the “Farmer” nickname rarely appeared in print. “Buck,” on the other hand, was used countless times in news articles—on occasion while he was still in Louisville, and very often afterward. Weaver was a man of many names. Early in his career, he was sometimes referred to as “Billy” or “Bill.” In the Lakin newspapers, “Will” often appeared. In formal or legal transactions, he usually went by “William B.” or “W.B.” He apparently had two aliases, as well, according to prison records. The aliases were “W.B. Mitchner” and “J.V. (or J.B.) Hamilton.”

9 The team, playing as the “Austins,” defeated the Giants by a score of 5-4 on November 14, 1887. The two teams played again the next day in a game that the Giants won, 19-13. Weaver played in both games, making three hits in nine at-bats.

10 “The Base Ballists,” Galveston Daily News, September 4, 1888, 6.

11 “Louisville Laconics,” Sporting Life, September 26, 1888, 3.

12 “Louisville Laconics,” Sporting Life, October 10, 1888, 3.

13 Bob Bailey’s articles about the 1889 and 1890 Louisville Colonels are the sources for information about the team’s historic milestones.

14 “The Association: Games Played Tuesday, August 12,” Sporting Life, August 16, 1890, 13; “In Too Fast a Class,” Syracuse Daily Standard, August 13, 1890, 5; “Fattened Their Averages,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 13, 1890, 5.

15 Seymour Siwoff et al, The 1990 Elias Baseball Analyst, 257. Charles F. Faber, Baseball Pioneers: Ratings of Nineteenth Century Players, 48. Faber reports Weaver’s 1891 outfield stats as: 132 games; 294 putouts; 33 assists; and, .956 fielding percentage. Baseball-Reference.com reports his 1891 outfield record as: 130 games; 290 putouts; 32 assists; and, .958 fielding percentage. According to the latter set of statistics, Weaver ranked first the American Association in putouts, and second in assists and fielding percentage.

16 “Milwaukee Merry,” Sporting Life, March 4, 1899, 10.

17 “Diamond Dust,” St. Paul Globe, May 2, 1901, 5 (reprinted from the Denver Times). Also see “Diamond Dust,” St. Paul Globe, May 4, 1901, 5.

18 “Lucas Talks in Butte,” Salt Lake Herald, September 9, 1902, 7; “’Buck’ Weaver Departs,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1902, 3; “’Frisco Team Plays Today,” Salt Lake Herald, July 21, 1903, 7.

19 “Boise’s Chances Are Very Bright,” Idaho Statesman, February 14, 1905, 5.

20 “Boise to Stay With League,” Salt Lake Herald, January 18, 1905, 7.

21 “Political Announcements,” Kearny County Advocate, July 9, 1908, 4.

22 Weaver last appeared in a Larned box score in a game against McPherson that occurred on June 18, 1910. His managerial record is inferred, and is based on the assumption that he left the team after that game.

23 “While On the Bench,” Hutchinson Daily Gazette reprint from the Great Bend Tribune, June 13, 1911, 3.

24 “While On the Bench,” Hutchinson Daily Gazette, June 8, 1911, 3.

25 “Sporting Events,” Lincoln Evening News, August 8, 1911, 6.

26 The Weavers may have had custody of at least one other child for a period of time. In 1922, James Ralph Weaver wrote to the Idaho Statesman, a Boise newspaper, in an attempt to track down Weaver, whom he stated was his foster father. The article about his quest leaves no doubt that the Buck Weaver he sought was indeed the one from Lakin. Yet, it is the only reference found indicating that James was a member of the Weaver family.

27 “Base Ball,” Wellington Sunday Press, July 3, 1887, 4; “Base Ball: Weaver as a Cop,” Sporting Life, December 31, 1892, 4; “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, July 14, 1900, 9.

28 Answer and Cross Petition filed by Dora Weaver, Defendant, Weaver v. Weaver, Kearny County District Court, Lakin, Kansas, December 1909.

29 KSP is now known as Lansing Correctional Facility.

30 “The Baseball Pennant,” and “What Team Will Play on Labor Day?”, Penitentiary Bulletin, August 16, 1912, 3 and August 23, 1912, 1.

31 The June 5, 1914 issue of the federal prison’s newspaper, Leavenworth New Era, included an article, “Kansas Licks the United States; United States Licks the Methodists,” which stated, “… It is the first time in prison history, to our knowledge, that one prison ball team has visited another and met in contest… ” Also, a nationally syndicated article published before the game described it as an “innovation.” While these articles are not definitive documentation of an historic “first,” the May 30, 1914 game was likely among the earliest inter-prison contests. The Leavenworth and Lansing communities are adjacent to one another, greatly facilitating the logistics for arranging an inter-prison game. In addition to the federal and state penitentiaries, the area also is home to the United States Disciplinary Barracks. Tim Rives, a researcher of prison baseball history, told the author that a game between inmate teams from the United States Penitentiary and USDB occurred not too long after the USP-KSP game.

32 Weaver’s death certificate contains an internal inconsistency. The document gives his birth date as March 23, 1865, but gives his age at the time of death (January 23, 1943) as 76 years, 10 months instead of 77 years, 10 months. As noted earlier, there also is a question regarding his actual birth date. If, as discussed in Endnote 5, he was born in December 1864 instead of March 1865, he would have been 78 rather than 77 at the time of his death.

Full Name

William B. Weaver

Born

March 23, 1865 at Parkersburg, WV (USA)

Died

January 23, 1943 at Akron, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.